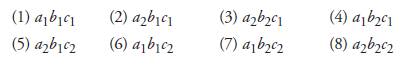

Consider the following eight experiments with combinations:

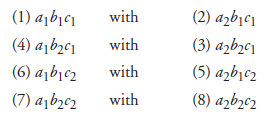

Out of these, each of the following four pairs provides results for comparing the effect of ^2 with that of ap

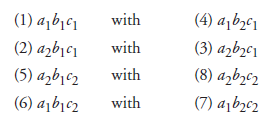

The other four pairs serve to compare the effect of b>2 with that of bp

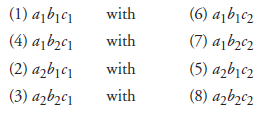

Finally, the following four pairs provide the bases to compare the effect of with that of cp

Thus, having done only eight replications with different combinations, it is possible to compare the effects of a, b, and c, each at two different levels, with each comparison evidenced four times. Yet another point is highly worthy of note. The effect of changing, for instance, a from level ap to a2 is available for our observation in the presence of four different combination of factors, namely, bpcp, b2Cp, b^, and b2Cj. And, when we summarize the main effect of a by averaging the four changes in the dependent variable, we are, in effect, getting to study the behavior of a in the company of all the possible associates. Needless to say, the same advantage applies relative to factors b and c.

On the other hand, a one-factor-at-a-time experiment for studying the effect of a, as an independent variable, consists of conducting two replications—one at each level of a, namely, a1 and aj, keeping the levels of b and c constant in both these experiments. And similarly, when b and c are independent variables, the other factors are kept constant. Let us say that the following combinations of a, b, and c were experimented on:

- a1, b1, c1 and a2, b1, c1 for the effect of a Suppose the combinations with aj were found to yield better effects than those with ay, from then on, ay would be dropped and no longer included in any further combinations.

- a2, b1, c1 and a2, b2, c1

If the combination with bj were found to yield a better effect, by would not be included in any further combinations.

- a2, b2, c1 and a2, b2, c2

If the combination with cj were found better, cy would be dropped.

In the above experiment scheme, in which aj is better than ay, bj is better than by, and cj is better than cy, each of these decisions is based on the strength of just one piece of evidence made possible by one pair of replications. Besides, this arrangement studies the “behavior” of the factors, each in only one company of associates. But as all experimental researchers know, or would be made to know, the outcome of a single experimental comparison as the means of evidence cannot be depended on. To gain the same level of confidence as in the scheme of experiment with designed factors, even ignoring the other possible association of factors, we need to replicate four times each pair of trials. That means the total number of trials is j x 3 x 4 = j4. Thus, the information provided by eight trials with designed factors requires twenty-four trials by the scheme of a one-factor-at-a- time experiment.

Source: Srinagesh K (2005), The Principles of Experimental Research, Butterworth-Heinemann; 1st edition.

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021