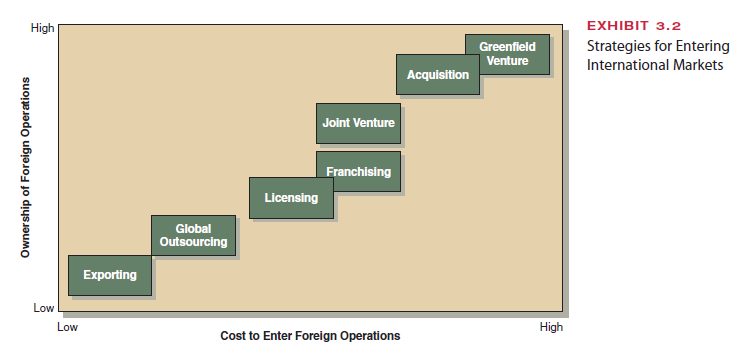

Organizations have a couple of ways to become involved internationally. One is to seek cheaper sources of materials or labor offshore, which is called offshoring or global outsourcing. Another way is to develop markets for finished products outside their home countries, which may include exporting, licensing, and direct investing. These market entry strategies represent alternative ways to sell products and services in foreign markets. Most firms begin with exporting and work up to direct investment. Exhibit 3.2 shows the strategies companies can use to enter foreign markets.

1. OUTSOURCING

In recent years, millions of low-tech jobs such as textile manufacturing have been out- sourced to low-wage countries. The Internet and plunging telecommunications costs are enabling companies to outsource more and higher-level work as well.13

Service companies are getting in on the outsourcing trend as well. U.S. data-processing companies use high-speed data lines to ship document images to Mexico and India, where 45,000 workers do everything from processing airline tickets to screening credit card appli- cations. British banks have transferred back-office operations to companies in China and India, as well.14

2. EXPORTING

With exporting, the corporation maintains its production facilities within the home nation and transfers its products for sale in foreign countries.15 Exporting enables a company to mar- ket its products in other countries at modest resource cost and with limited risk. Exporting does entail numerous problems based on physical distances, government regulations, foreign currencies, and cultural differences, but it is less expensive than committing the firm’s own capital to building plants in host countries.

A form of exporting to less-developed countries is called countertrade, which is the barter of products for products rather than the sale of products for currency. Many less- developed countries have products to exchange but have no foreign currency. An estimated 20 percent of world trade is countertrade.

3. FRANCHISING

Franchising is a special form of licensing in which the franchisee buys a complete pack- age of materials and services, including equipment, products, product ingredients, trade- mark and trade name rights, managerial advice, and a standardized operating system. Whereas with licensing a licensee generally keeps its own company name and operating systems, a franchise takes the name and sys-tems of the franchisor. For example, An- heuser-Busch licenses the right to brew and distribute Budweiser beer to several brewer- ies, including Labatt in Canada and Kirin in Japan, but these breweries retain their own company names, identities, and autonomy.

In contrast, a Burger King franchise any- where in the world is a Burger King, and managers use standard procedures designed by the franchisor. The fast-food chains are some of the best-known franchisors. KFC, Burger King, Wendy’s, and McDonald’s out- lets are found in almost every large city in the world. The story often is told of the Japanese child visiting Los Angeles who excitedly pointed out to his parents, “They have Mc- Donald’s in America.”

Licensing and franchising offer a business firm relatively easy access to international markets at low cost, but they limit its partici- pation in and control over the development of those markets.

4. CHINA INC.

Just as managers at Delphi are looking to China as the wave of the future, many companies today are going straight to China or India as a first step into international business. As we discussed, business in both countries is booming, and U.S. and European companies are taking advantage of opportunities for all of the tactics we’ve discussed here—outsourcing, exporting, licensing, and direct investment. In 2003, foreign companies invested more in business in China than they spent anywhere else in the world.16 Multinationals based in the United States and Europe are manufacturing more and more products in China using de- sign, software, and services from India. This trend prompted one business writer to coin the term “Chindia” to reflect the combined power of the two countries in the international dimension.17

Outsourcing is perhaps the most widespread approach to international involvement in China and India. China manufactures an ever-growing percentage of the industrial and consumer products sold in the United States—and in other countries as well. China pro- duces more clothes, shoes, toys, television sets, DVD players, and cell phones than any other country. Manufacturers there also are moving into higher-ticket items such as auto- mobiles, computers, and parts for Boeing 757s. China can manufacture almost any product at a much lower cost than in the West. For its part, India is a rising power in software de- sign, services, and precision engineering.

JPMorgan Chase announced plans to move 30 percent of its investment bank back-office and support staff functions to India by the end of 2007 to take advantage of the low cost of highly educated workers.18 Nearly 50 percent of microchip engineering for Conexant Sys- tems, a California company that makes the intricate brains behind Internet access for home computers and satellite-connection set-top boxes for televisions, is done in India.19

Many large organizations also are developing joint ventures or building subsidiaries in China and India. Cummins Engine was one of the earliest U.S. firms to open plants in both countries.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Really great visual appeal on this internet site, I’d value it 10 10.

naturally like your website but you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very bothersome to tell the reality nevertheless I will surely come again again.

Well I really enjoyed studying it. This tip procured by you is very useful for correct planning.