Organisation and method has been defined in many ways but perhaps the most succinct is that it is ‘the organised application of common sense applied to office work to avoid or eliminate waste’. The use of the term ‘common sense’ is very relevant here because so many of the problems encountered in O and M investigations can be solved by its application.

The function of O and M is first to examine clerical procedures critically to discover where improvements can be made for greater economy or effectiveness and second to design and install new procedures and systems where necessary. The first is a task very often neglected. Even where a system or procedure was carefully designed when first installed it frequently becomes inefficient for several reasons.

In a growing organisation, when work becomes too much for the existing staff all too often the trouble is remedied by engaging additional staff rather than by examining what is being done to see whether improved methods might solve the problem with the existing personnel.

Mention has already been made of the production and retention of unnecessary records and of the continuance of obsolete procedures. Two other reasons for the existence of unnecessary work can also be mentioned. Often, when a senior executive asks for information that is not produced as a routine, this is specially prepared: so as not to be caught out in case a similar request is made in the future a procedure is sometimes installed so that the information is always available on file. This is, of course, extremely wasteful. The other reason occurs in organisations where the status of managers or supervisors is measured to some extent by the number of people they control: there is no incentive for these officers to seek ways of reducing their staff. In all these cases O and M investigations would show many benefits.

The practice of O and M is one requiring a wide knowledge and experience of the whole range of clerical activities and also of the wide range of office machinery and equipment available. It comprises numerous techniques and requires the application of a critical, analytical and creative mind. In this chapter it is possible only to introduce the subject: a full treatment of O and M would require a volume in its own right.

When O and M is discussed the term work simplification is frequently used. The precise meaning of this description is open to interpretation

and it must be read within the context that it is used. To some authorities it is a synonym for organisation and method: to others it describes the practice of making procedures and parts of procedures simpler whilst not involving a complete O and M investigation.

1. Who Should Carry Out O and M?

There are three possible choices of personnel to carry out an O and M assignment:

- The office manager or one of the senior office supervisors.

- An O and M department set up for this purpose.

- An independent consultant or consultants.

Although 1 is the least costly choice, except for very simple assignments this is not the wisest one. The conduct of an assignment, to be really effective, requires the person or persons doing the investigation to have the following attributes:

- Complete freedom from day-to-day duties.

- Be absolutely objective and unbiased.

- Have a wide experience of office methods and machines, gained over a wide area.

- Be able to go wherever the assignment requires without embarrassment.

- Have the right to go all the way to top management with ideas and recommendations without being inhibited by top management’s authority.

It will be obvious that any member of the office staff, even the office administrator, will not be able to meet all the attributes mentioned and this is therefore the least effective way to have an assignment conducted.

The setting up of a complete O and M department is a solution frequently pursued by large organisations. This is very effective because most practitioners of O and M are objective and independent-minded. Such departments are normally recruited specially, which aids their objectivity.

Independent consultants are most likely to have all the qualities required but, unfortunately, most are quite expensive to employ, particularly when it is remembered that an assignment may go on for a long time. Some trade and professional associations provide an O and M consultancy service for their members and these usually charge significantly lower fees than independent consultants.

2. To Whom Should O and M Report?

There are a variety of opinions as to whom the O and M team should report. Much will depend upon the size of the organisation, how it is organised (namely, centralised or not) and by whom the assignment is being conducted. Almost invariably, if the assignment is being carried out by an independent consultant, reporting is to the undertaking’s chief executive or a senior officer appointed for the purpose. When an O and M department has been set up the initial reports will be to the head of that unit. Thereafter responsibility may be to the chief executive, the organisation’s secretary, the chief accountant or other responsible officer. Where the O and M section is part of a wider management services department the reporting will be through the head of O and M to the head of management services who will then report to a member of senior management as already discussed. Specially appointed O and M personnel, such as a senior office supervisor, accountant or similar officer, should be required to report direct to a senior executive, preferably to the chief executive if the assignment is of sufficient importance.

The suggestion that O and M reporting should be to the office administrator or to the head of the section subject to the assignment is often made on the premise that such officers are best fitted by their intimate knowledge of the procedures and systems involved. It can be argued, however, that because they are so close to the work concerned they are likely to find it difficult to be completely objective, particularly if they were instrumental in designing or installing the procedures or systems in the first place. On the whole it is the general opinion that reporting should be to a separate officer, as high up the management hierarchy as possible, so that complete objectivity can be achieved. However, it must also be said that the head of a department or section subject to an assignment must be involved in the report and the discussions arising.

3. Costing an Assignment

The ultimate cost of an O and M investigation is virtually impossible to estimate in advance simply because it is not possible to predict where the investigation may lead and thus how long it will take. However, a system of costing the investigation whilst it proceeds should be established and possibly a budget drawn up to limit the total expenditure, so that control may be exercised over the costs of the investigation. As in any other form of activity costs will involve hours spent and materials and services used.

However, if the recommendations made when the investigation is completed are put into practice the predicted savings should be set against the cost and the possible future savings ascertained. In other words, an effective O and M exercise should result in a profit and not a net cost. Furthermore, some of the results of an O and M investigation are in quality improvements (improved layout of accounts may be one example) and are not quantifiable in cash terms.

4. Organisation

The service we are discussing is called organisation and method. Much is made of the method side but very little of the organisation aspect. Yet this can be fundamental to the success of a modified procedure or system: in fact, on occasions reorganisation can effect savings with very little change in actual methods. An example of how a change in method can produce a change in organisation is that of the introduction of a centralised dictating system. No longer will executives have personal secretaries who will be constantly available to take notes, to find addresses and figures for correspondence and so on. In fact, the executives’ authority over this part of the secretarial function will disappear and it will be in the hands of the typing pool supervisor. The pool will be at the executives’ service but not at their command.

For the O and M officer organisation must follow, fundamentally, what was discussed in Chapter 3, but for the clerical function it is essentially a part only of the whole, though the tenets are the same. O and M is essentially concerned with specialisation (discussed in the previous chapter) and the organising of jobs on this basis. It is also interested in delegation and the rules of span of control, and will define very clearly areas and limits of responsibility and authority as well as duty. What can be said is that O and M is less concerned with the classic principles of organisation and much more concerned with practical application.

5. Method

As has been suggested, O and M is primarily concerned with method – the way things are done – and is charged with improving methods to make them more effective, cheaper or quicker (or, of course, all three).

Methods have changed and are changing all the time. Some of this is because of natural evolution, but most of the changes have come about through the efforts of O and M people. What was the result of the efforts of an O and M team in one organisation very often becomes the accepted practice later. Two examples are photocopying and the use of embossed credit cards.

Not so very many years ago obtaining a copy of an existing letter or other document meant work for the copy-typist. Hours were spent on this chore with the resultant risk of copying errors which, in turn, entailed additional checking for correctness. Now, of course, any office establishment with a reasonable copying need provides its staff with a photocopying machine or machines. The result is speedy, accurate copies which need no checking. Similarly, the use of the embossed credit card has provided a simple credit and customer checking device in place of the previous, cumbersome methods of manually checking creditworthiness and customer identity.

6. Stages in an O and M Assignment

There are a number of stages in an O and M assignment, the successive application of which results in a new or improved procedure or system. They may be enumerated as follows:

- Select the problem for investigation

- Collect and record the current method by the most appropriate means.

- Analyse each stage of the existing procedures.

- Develop improved or new procedures

- Install and implement the revised methods.

- Maintain the new methods until they work smoothly.

6.1. Selection for examination

The need for an O and M investigation can come about in a number of ways. In some organisations there is a regular review by the O and M team of all office systems and procedures rather on the lines of a perpetual audit. In this way all the operations of the office are looked at objectively over a length of time to ensure maximum efficiency in the clerical function. A second way is for there to be a review only of those areas where difficulties, delays or high work pressures occur. A third is for specific requests to come from office personnel at all levels for assistance where a problem arises in a particular procedure. However the assignment arises, the objectives of the subject of study must be clearly ascertained.

6.2. Collecting and recording facts

The present work methods must be ascertained carefully and fully and appropriate records made. Investigation may be by observation of staff at work, questionnaires or any other suitable means. The facts ascertained are initially recorded in note form in the main, but any other means may be used if more suitable.

6.3. Analysis of present method

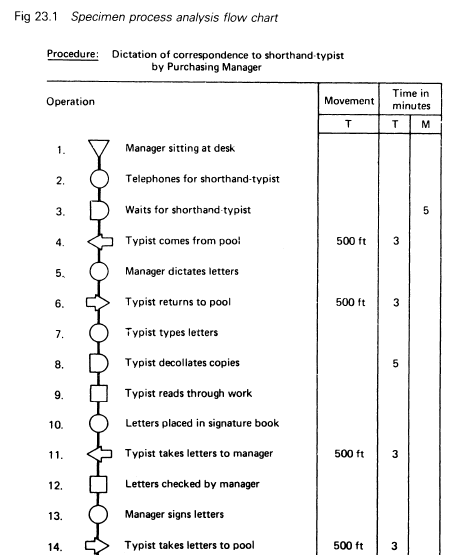

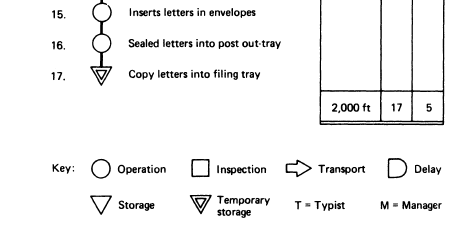

In order to be able to study the data collected the O and M investigator will usually make use of various charts which show graphically and therefore more clearly, the problem spots which need attention. One of the most commonly used charts is the process analysis flow chart (also known by many other names such as procedure analysis flow chart). Two narrative-type statements used are the procedure statement and the procedure narrative. Speciments of these three aids to analysis are given in Figures 23.1-23.3.

6.4. Developing an improved method

Armed with the analysis just mentioned the O and M officer can develop new and improved methods which, again, may be shown in chart form from which new procedures can be written. Revised flow charts can be drawn and compared with the originals, these showing the improvements proposed. Revised narrations are also written.

6.5. Installing a new method

It is usually deemed preferable for the O and M team to install a new method on the basis that they know it intimately and are best qualified to put it into practice. Objectors to this maintain that the O and M people then take on, however briefly, the authority of line management whereas they are strictly only advisory and that this can cause confusion in the minds of the workers involved in the new procedure.

A compromise is, therefore, often reached where the line supervisors are briefed by the O and M people and actually give instructions for the installation of the new method whilst the O and M team maintain an advisory presence.

6.6. Maintaining the new method

It is the responsibility of the O and M team to ensure that the new method works satisfactorily. They must, therefore, maintain a watching brief until this is established. Here again, it may be more diplomatic for the line supervisors to have the prime contact with the workers, reporting to and being supported by the O and M officers.

7. Charts used in O and M

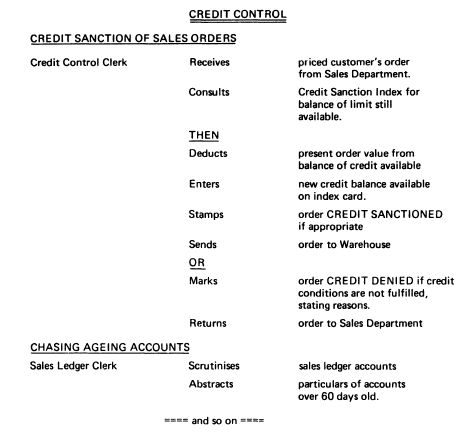

Mention has already been made of the process analysis flow chart and the procedure statement and procedure narrative. Many other charts are used by practitioners of O and M, specimens of two of which are given in Figures 23.4 and 23.5.

Two points must be emphasised here. First, there is no absolute standard nomenclature relating to charts and each O and M practitioner will have his own names for the charts used: neither is there a standard in the design of the charts themselves, which are devised solely according to the need as it arises.

Second, these charts are not the prerogative of O and M practice: they are freely used in connection with any problems relating to the office function, including the question of work control which is discussed in the next chapter.

8. Carrying out an O and M Assignment

Before an O and M investigation can get under way the area of the investigation must be determined. The need may have come about for a number of reasons, the most common being:

- To reduce costs.

- To simplify a procedure to make it easier to operate.

- To deal with bottlenecks and ease work-flow.

- To speed up work-flow generally.

- To deal with problems arising through expansion of work.

- To improve coordination.

Because a full assignment can be lengthy, and therefore expensive, and because an apparent cause for dissatisfaction may not be the true cause, it is usually advisable for the investigator to make a preliminary survey and to present a brief report on the proposed project.

This report will enable the cost of the assignment and the possible savings to be assessed and thus determine whether a full investigation is justified. In addition, the probable lines of investigation can be stated so that, before anything is put into action, management and the departments concerned will be able to make the necessary arrangements if the complete project is to be carried out. It must be stressed that any assignment of this kind must have the full backing of management and acceptance by heads of departments if it is going to be worthwhile.

The subject of the assignment having been ascertained and the necessary authority having been given for it to go ahead, then the investigation can begin.

8.1. Getting the facts

The first step is to verify the purpose of the present procedure: this means to establish its primary and secondary objectives. As has already been mentioned, very often the purpose of a procedure may have changed or may have disappeared altogether but, nevertheless, it continues to be carried on in the same old way.

This step is termed verification of purpose and in attempting to simplify the procedure it may be found that some step or stage, or even a whole routine, may be unnecessary, or its purpose may be out of date through change, present cost or some other reason. An example will illustrate this.

Is dictation still given to shorthand-typists? What purpose does the writing of shorthand achieve? Would it not be cheaper and more efficient to use a dictating machine?

Then there is the question of what O and M people call ‘sacred cows’. These are practices that have become sacrosanct and untouchable, mainly by reason of long custom or because of prejudice. An example of the first is the practice of sending copies of all outgoing letters to the department head (who never reads them) and of the second the prejudice against putting prices on delivery notes when the multi-part invoice/delivery note sets are typed, even though this would simplify this procedure. In very many O and M assignments the most rigorous resistance is offered when suggestions are made to eliminate or modify these sacrosanct practices even when it can be proved that they are wasteful and costly.

Having verified the purpose of the procedure or the system, the second step is the practical business of finding out what is actually done. Although a certain amount of information can be obtained by talking to the office administrator, the office supervisor and other supervisory staff, inspecting the current procedure manual (if any) and requiring questionnaires to be completed by the staff, by far the best way to obtain information is to interview staff and to observe them at work. This calls for a great deal of tact on the part of the investigator and tact might be said to be one of the essential skills of the O and M practitioner. The reasons are not far to seek.

- Any investigator is subject to suspicion. Some workers will be afraid for their jobs and exhibit this by being evasive and may be quietly uncooperative.

- Some workers will give the investigator the answers they think that he or she wants; others will exaggerate to give a good (or adverse) impression.

- Most workers have their own jargon.

- The workers have probably never looked at their jobs objectively and have difficulty in describing them clearly.

- Most workers are very busy and do not welcome the interruptions that are inevitable in an investigation.

To take an example of 3 and 4: a purchase ledger clerk is asked ‘What do you do?’ and the reply is ‘Well, I receive a batch of RAs from the computer and file them. I then get a batch of CP listings from Cash. I go through the RAs with the CPs and mark up the RAs. An O/S list is given to Mr Tidmarsh once a fortnight.’

To the uninitiated this is virtually incomprehensible, and to the knowledgeable an incomplete story. The clerk thinks all the information has been given but, of course, it has not. All interviews must, therefore, be planned with great care and with a completely open mind, and with the recognition that the interviewer may need the help of the interviewees in interpretation.

As with interviewing, the observation of work actually being done also requires tact and diplomacy. In addition, staff must be informed before the observations that they are going to take place and, of course, the recordings must be accurate. Initially it will not be a time study, though this may come later. What has to be ascertained is exactly what is being done. In other words, it is a study of the present method.

If we go back to our example of the purchase ledger clerk, the investigator will observe what the clerk actually does when the RAs are received and filed. So each step will be watched and noted for subsequent analysis. Speed of movement is of no concern at this stage; just how the work is done.

When planning the interview, whilst conducting the interview and when subsequently studying the facts, the O and M practitioner must keep in mind what might be called the adverbial questions, WHAT, WHERE, WHEN, WHO, HOW and WHY. WHY is the most important and should always be the concluding word when using the other five. This may be illustrated as follows:

WHAT do you do? (is being done?) andWHY?

WHERE do you do it? (is it being done?) and WHY there?

WHEN do you do it? (is it done?) and WHY at that particular time?

WHO and is it constant or not? does it in addition to you? does it when you are absent?

HOW and WHY these people? do you do it? (is it being done?) and WHY is it done in that particular way?

Inquisitiveness is the main characteristic of the O and M operator, and WHY is the main preoccupation.

Some of the points that can be looked for particularly in endeavouring to simplify procedures are shown below, but there are, of course, many more:

- Is anything written more than once? If so, some form of duplicating or circulation of documents might provide a saving.

- Absolute accuracy is costly. Is the need for such accuracy justified in every case where it occurs?

- Controls, also, are expensive and often prove valueless in the event. The value of any control is what it saves and not what it costs. Can any controls be reduced or eliminated?

- Look at the office layout. Is there too much staff movement?

- Are the layouts of forms and letters designed to save time; and are forms easy to read and understand? Is machine tabulation reduced to an absolute minimum?

- Are reference numbers and codes common throughout the organisation? Some undertakings use different references in different departments for the same things, wasting time and creating opportunities for errors.

- Is there an unnecessary insistence on convention? Does every letter, for instance, have to be typed and every telephone call confirmed in writing?

9. Evaluation of Method

When a new procedure has been formulated and installed it is essential that its effects be verified to ensure that it achieves the objectives set.

This is known as evaluation and is most easily shown by a checklist, an example of which might be as follows:

- To what extent have the defined objectives been achieved?

- Do the achieved benefits meet the suggested benefits set out in the original recommendations?

- Do the operating costs of the revised procedure or system match those suggested when the assignment was authorised, and what are the savings produced over the operating costs of the original methods?

- During the actual operation of the new methods have any modifications appeared to be desirable?

- Have the employees involved accepted the new procedures and do they work the new as well as they did the old? Have any retraining needs been satisfactorily met?

The extent to which these questions can be satisfactorily answered is the measure of the success of the assignment.

10. Clerical Work Study

Work study has been an established practice in the factory for a very long time and it is now being accepted in the office. It consists of two elements: method study and work measurement. Method study has been dealt with under organisation and method and concerns itself with the way things are done. Work measurement, on the other hand, seeks to discover how long a job takes, or should take. It follows, therefore, that work study should not take place until methods have been investigated and improved where necessary.

It must be emphasised here that work measurement is the province of the expert who has had proper training and experience. Unless properly qualified, therefore, the office administrator should not attempt to carry out a work measurement assignment, nor should staff, however senior, be expected to do so either. The following notes, therefore, on the scope and some of the practices of work measurement will serve as an introduction to the subject for those engaged in office administration.

Work measurement as practised in the factory is very precise, jobs being split up into very small elements which are independently timed. Various additions are made for relaxation, personal needs, special working conditions, monotony, posture and so on, and a split-second stopwatch is used to make the timings. Added together these elements constitute the time for a job. This precise approach is possible in the factory because, on the whole, tasks are absolutely repetitive; one job is exactly like the one before it and the one before that, and the next will be the same as the current one.

It used to be said that office work was not sufficiently repetitive to be a field for work measurement and that mental effort cannot be measured anyway: and when one thinks of the sales clerk dealing with customers’ queries, or the estimator working out a tender, this appears to be very true. However, much office work is, in fact, routine and has enough of the repetitive element in it to lend itself to measurement, examples being copy-typing, audio-typing, indexing, machine operation and so on. Further, of course, the office has become highly mechanised and such jobs as data entry present few difficulties in this direction.

The objective of clerical work measurement is to determine time standards for given quantities of work to enable it to be planned and controlled, to provide information for staffing and so on. This will permit the putting into effect of the following:

- Set standard levels of output for workers: this will also enable bonus and incentive schemes to be designed.

- Spread the work-load evenly and fairly over the relevant staff.

- Give the necessary information to estimate staffing levels and equipment requirements for given volumes of work. This is particularly useful for achieving target dates for completion of jobs.

- Calculate standard costs for clerical work budgets.

- Provide standards of performance criteria for training purposes.

The principles of work measurement are:

- To determine a fair rate of work to be expected from a normal worker under normal conditions.

- To provide standard times in particular services for special conditions which will alter the average work pace, such as poor lighting or heating, inefficient equipment, uneven work-loads and the like.

- To seek out and remedy any circumstances that mitigate against a steady work-rate or work-flow.

11. Methods of Work Measurement

So far as the office is concerned the following are the main methods of work study.

11.1. Calculation from past records (broad measurement)

In this the past production of an adequately long period is taken and the man-hours or man-days divided into the total output to produce an hourly or daily output figure. Suppose, for instance, over a period of 65 working days five invoice clerks priced and extended 12 025 invoices: this would give a standard output of 37 invoices per day per clerk.

It is claimed that this is an acceptable measurement method to most office workers provided that they are told what is happening, but it is, of course, a very dubious method. Certainly it takes into account all the variations and special factors involved automatically, though adjustments would have to be made for staff absences and similar occurences. But we do not know whether the clerks were working effectively, whether they were wasting time at times, or whether they were under pressure frequently or occasionally. Memories can be honestly or deliberately unreliable. Nevertheless, it is better that no measurement at all.

Should past records be inadequate or otherwise unreliable, then current work can be measured using (with their agreement) workers of average performance and output. This measurement should be over several periods and the length of time never less than about 20 minutes nor more than an hour at a time. In this case adjustments for fatigue, relaxation and the like will have to be made, say 10 – 15 per cent, to obtain a fair picture.

It is interesting to note here that some O and M practitioners prefer to carry out the work themselves for this type of measurement rather than subject staff to observation.

11.2. Time study

This is a highly specialised technique, which has already been described under work measurement. Several observations are made and an average taken so as to eliminate any exceptional cases. It has been found that many clerical workers resent the use of a stopwatch and where this is the case the work study operator makes use of a conventional clock or watch. This, of course, means that the measurements are not so accurate and the exercise may become more of a broad measurement observation.

11.3. Predetermined motion time systems (PMTS)

This is a method where times previously established for human motions, such as reaching, grasping and so on, are used to provide a standard time for a given job, which has been broken down into its component movements. This method is claimed to provide higher accuracy than the observed method when working out standard work times. It also, of course, avoids the necessity for direct observations.

11.4. Activity sampling (or work sampling)

This technique involves the making of a series of observations at random times over a period of time, the activity being carried on at the occasion of each observation being recorded. Examination of the total of observations can provide information as to the total effectiveness of a group or an individual.

An example will clarify this. Suppose out of 1000 observations of a group of card punch operators, 600 are recorded as key-punching. It can then be calculated that the group spends 60 per cent of its time actually punching cards.

Only work that can be easily distinguished during a short observation can be measured in this manner, and it is imperative that a sufficient number of observations are carried out to ensure that normal variations in the work and its flow are covered.

Few of the more precise methods of work measurement are appropriate to the majority of office jobs and, it must be repeated, where they are used they should always be applied by those experienced in the techniques. Lack of expertise in applying the methods can produce very erroneous results.

Source: Eyre E. C. (1989), Office Administration, Palgrave Macmillan.

12 Jul 2021

12 Jul 2021

9 Feb 2018

12 Jul 2021

12 Jul 2021

12 Jul 2021