In order that the office may run in a smooth and efficient manner it is essential that the work carried out be adequate to provide an effective service both from the point of view of quality and of quantity. This being so, it is necessary to establish certain controls to ensure the attainment of these objectives. Controls also enable the best use to be made of clerical staff and of equipment.

1. Quality Control

Quality in clerical work is, essentially, freedom from errors and this is what quality control concentrates on. Other aspects of quality, such as the appearance of letters, neatness, tidiness and the like cannot be quantified and, thus, control of these must rest with observation by supervisors.

The three main methods in use to control the quality aspect of clerical work are: (a) one hundred per cent check, (b) spot checks and (c) statistical quality control.

One hundred per cent check means that every part of the work done must be checked; in effect, the work is virtually done twice. For instance, in pricing and extending items on sales invoices each price and each calculation will be done again by a second person. This is, of course, very expensive and is resorted to only in cases where absolute accuracy is essential. An example would be checking the items in an important quotation or tender where an error of overpricing may lose the contract or one of underpricing may lead to the contract being won but money lost on it.

In order to save some of the cost of this type of check some organisations carry out a total check of only those items which exceed a minimum amount. However, it must be recognised that items appearing below this minimum may be in error to a considerable extent: it is not difficult to omit a nought from the end of an amount, for example, and the figure shown as 24 should, perhaps really be 240.

Spot checking is the checking of batches of work at regular or irregular intervals. It does not rest on any statistical base and is, therefore, not a scientific method. Nevertheless, it is suitable for a great deal of clerical work where the results of errors will not have serious effects or where any errors will show up later but before a substantial amount of further processing is done.

In operating this method irregular checks are more likely to keep staff error-conscious than regular checks, but they may be more difficult to implement. Checking copy letters for typing and spelling errors is an example of an area that lends itself to spot checks.

Statistical quality control is a truly scientific method. Statistically determined random samples of constant size of the work to be checked are taken and the percentage of error determined. The incidence of error at a sampling is compared with a scale of previously-established acceptable error rates, these acceptable rates having been determined by a previous survey. If the incidence of error in the sample falls within the scale then no action is taken. However, if the sample shows an error rate greater than the upper limit of the scale an investigation for the cause or causes may be instigated. It is usual to plot the error rates shown by the samples on a graph, which also visually indicates trends of proneness to error and, therefore, alerts those responsible where the tendency is rising.

Like any statistical method, statistical quality control should not be attempted without expert advice. It is not, in fact, a common method in the office, but the increase in mechanisation and in the use of the computer in clerical work means that its installation is becoming increasingly facilitated.

Variations of these three methods will be found in different organisations: each method of control will have been formulated to suit the work being checked. Two fundamental points must be made about quality control checks, however. The first is that such checks should be done as near to the time of the original task as possible so that errors are discovered before further processing is done and the errors compounded. The second is to ensure that corrective action is taken on the errors that are shown up. Sometimes this is not done for one reason or another, but it must be emphasised that ignoring errors has a deleterious effect on the future quality of work.

1.1. Discovery of errors

Quality control is the usual source for the discovery of clerical errors, and involves either routine checks put upon work or by special scrutiny or audit. However, errors are also brought to light in a third and unfortunate way, this is by complaints from outside, from customers, suppliers or other outside organisations with which the undertaking has to deal.

Such complaints indicate that the controls instituted are either inadequate of themselves or are not being properly applied. If such incidents are numerous it is essential that an investigation is made to find the reasons so that remedial action may be taken without delay. Complaints from customers are the most serious because they may lead to a loss of goodwill and the possible loss of valuable orders.

1.2. Causes of clerical errors

Whilst it is easy to blame clerical staff for errors the fault does not necessarily lie with the workers. Management should examine its own record in regard to selection procedures, training and supervision because here inadequacy can lead to workers being engaged for jobs for which they are not fitted, for which they are not adequately trained or in which they are unsatisfactorily supervised. Poorly designed procedures and forms can also lead to clerical errors not of the workers’ making. Lastly, morale may be low because of a number of reasons such as a faulty staff relations policy, low pay, faulty or obsolete equipment and poor working conditions.

Where errors are directly the responsibility of staff these are mostly caused by carelessness or lack of concentration, tiredness and domestic problems causing worry. Lack of knowledge and skill may also be laid at the door of a worker, but this is probably more the responsibility of the employer than of the clerk, as just explained.

2. Quantity Control

In order that the amount of work done can be controlled it is necessary to set standard levels of output so that comparisons can be made between them and the actual work done. If a formal work study programme has been carried out then standards will already have been established in the average case.

What unit to measure to set the standard and to check output thereafter is the first consideration. Routine or repetitive work is the most easily measured, particularly for individual output, and so is the easiest for which to set a unit. Key-punching, copy-typing and similar work lend themselves, for instance, to units such as key-strokes per second, lines per minute and so on. In such cases, of course, periods of time greater than these must be used for actual measurement. In most routines there will not be the exact regularity as found in the factory and averaging is thus necessary. Suppose, for instance, that we take four key-strokes per second as a standard for key-punching: it must be recognised that the punched cards will differ one from the other in content and number of holes. Cards punched over an hour, reduced to key-strokes per second, will permit the establishment of the standard unit and volumes achieved. Similar remarks apply to copy-typing and other such routine jobs.

Where output per individual is not reasonable to measure, group or departmental output is a more suitable alternative.

In making the preliminary assessments the greatest tact must be exercised to avoid the resentment of workers, or their anxiety. Their complete cooperation must be won and to this end the units chosen and methods of measurement adopted must be patently fair and reasonable. The samples of work being studied and the workers whose output is being measured must all be what are considered to be average. Especially simple or easy work samples should be avoided and the workers should not be those whose work-rate is known to be above average. On the other hand, so that the results of the study are worthwhile and will contribute to overall efficiency, the work samples should not be too difficult nor the workers being measured too slow. Above all, the workforce should be made aware of the basis being used for measurement, should understand it and know why it is being used. It must be agreed with them and seen to be absolutely equitable.

The actual checking of the quantity of work done in the normal course can be carried out by the supervisor or, alternatively, the workers concerned can be issued with work sheets that they enter up themselves showing their output. In many cases, as with quality control, a one hundred per cent check is not essential: much will depend upon the type of work or worker, and whether there is a bonus scheme in operation for above-standard achievement.

3. Work Scheduling

Several methods have been evolved for controlling the quantity of work produced, all coming under the general heading of work scheduling. The adoption of work scheduling assists in achieving the following:

- It helps to ensure that work is completed by the time required. This is most important in some procedures such as wages.

- It assists in producing an even flow of work and in avoiding bottlenecks.

- It facilitates an even distribution of work and promotes proper staffing levels.

- It can indicate the necessity for remedial action, where this becomes necessary, in good time to avoid delays and so ensures an adequate work-flow. This is very much related to 1 above.

Four ways of scheduling work are particularly applicable to the office, the first being the simplest and probably the most commonly used. The remaining three require more supervisory effort in recording and checking and are not so readily put into practice.

- The folder system. In this method the work is batched into specific quantities and inserted into folders. Starting and finishing times (or time allowances) are indicated on the folders, which are distributed to the workers. The supervisor maintains a schedule of the folders issued and can quickly see where working is being delayed.

- Visible card indexes. This method is appropriate where lengthy jobs are involved and, particularly, where the work can be divided into sequential sections. A card is prepared for each job and signals are used to indicate progress. Provided the signalling is kept up to date the progress of each job can be readily seen at a glance.

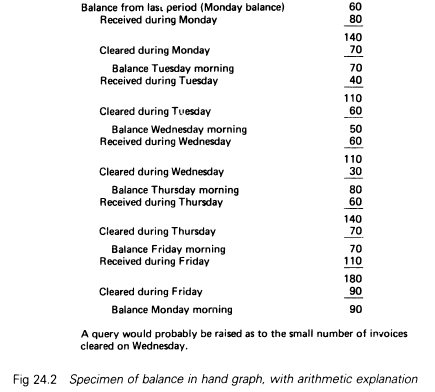

- This is done in several ways but all entail giving specific starting and finishing times (or dates) for each operation and keeping a tight check on progress. In many jobs a simple form ruled to show requirements and attainments is adequate. Other means available are proprietary wallcharts and boards with sliding indicators. A most effective control, however, is the Gantt chart, a specimen of which is given in Figure 24.1.

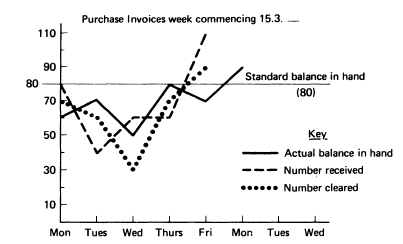

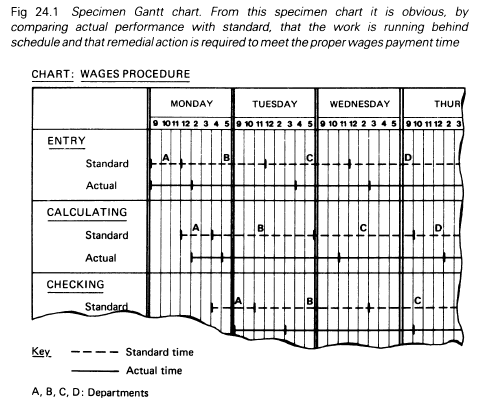

- Balance in hand. Where the flow of work inwards fluctuates a great deal the establishment of a fixed maximum balance of work in hand is useful. This method is particularly appropriate where the operation is continuous and the source of the input is not under the control of the department. A typical instance is the receipt of purchase invoices. It is usual to maintain graphs to record the work flow, an example of which, together with an arithmetic explanation, is given in Figure 24.2.

4. Excessive Work-loads

However well work is planned and controlled there are times, sometimes only occasionally and sometimes at regular and known times, when the work-load exceeds that within the normal capacity of the staff concerned. The ways in which this problem is usually dealt with include the following:

- Working overtime. This is a common way of dealing with excess work, particularly in such departments as wages where there is a tight time limit and the extra work occurs only about once a week. Normally overtime working is a practice to be discouraged as a regular feature of office work and the procedures and systems should be carefully reviewed to discover the reasons for it so that, where possible, they can be modified to avoid the necessity for overtime.

- Staff interchange. There should be some flexibility in staffing so that individual clerical workers can be employed on a variety of jobs. This was touched upon in Chapter 16 under ‘job satisfaction’, but many large employers make a point of circulating new staff through several departments so that experience is gained of a variety of different operations. This greatly assists the possibility of staff interchange. It seldom happens that all departments are under stress at the same time and if staff have a variety of skills they can be interchanged easily, those experiencing a slack period being loaned to a department with a work overload.

- Rearranging work. It often happens that work is structured so that all the tasks in a procedure are done as they are required. In many instances, however, some of the tasks could be done prior to the peak time, which would even out the work-load. An example is that of addressing envelopes. At creditor payment time, which can involve a temporary, heavy work-load, it is common for the envelopes to be addressed at the time the cheques are prepared for mailing. If the envelopes are prepared in advance and stored under indexes the work can be spread over a longer time and the peak avoided or, at least, reduced.

- Part-time help. Where there is a continuous requirement for extra help which does not warrant an addition to the full-time staff then part-time workers can be engaged. Often such part-time workers are past employees, such as women staff who have married and given up full-time employment. Such workers can be extremely valuable.

Part-time workers who have not previously worked for the organisation will, of course, require some training.

- Roving staff. Organisations who have many depots or branches sometimes employ groups of itinerant workers who are required to attach themselves to any part of the organisation as and when needed. This method is largely used to cover holiday periods and prolonged absences through other reasons, but can be usefully employed to assist at times of work overload. The commercial banks are an example of the type of undertaking that finds this method useful.

- Service bureaux. Many jobs that would be a burden to staff can be passed out to service bureaux, who will undertake almost any of the routine office jobs such as duplicating, envelope addressing, punching cards and the like. Besides helping in emergencies these bureaux can also be usefully employed in regular routine work to save engaging extra staff, an example being the regular circularising of customers.

5. Budgetary Control

So far we have looked at the control of the actual work of the office. The ultimate effect aimed for is, of course, to control the operating costs of the clerical function. A more direct way is to control actual expenditure by placing limits on it and the principal way to do this is by means of budgetary control.

A budget is a forecast of future expenditure and budgetary control is the monitoring of actual expenditure against the forecast so that reasons can be determined for variances and so that remedial action can be taken if required. Our concern here is with the administrative budget (the budget for administration expenditure) but it must be remembered that this budget, along with other departmental budgets, forms part of an overall, or master, budget for the whole organisation.

5.1. Preparing a budget

First the level of permitted expenditure must be determined and this is based on a planned level of total activity. In an industrial or commercial enterprise the determining activity is usually sales volume, whereas in other types of undertaking it will be the expected demands on resources to fulfil the undertaking’s main functions. The allowable expenditure on the items making up the budgets will then be determined, based on past experience and forecasts of future trends in prices and charges. Objection may be taken to the use of the term ‘forecast’ instead of ‘plan’ or ‘planned’ in connection with expenditure. Certainly the extent of the determining activity can be planned (for example, sales volume) but the revenue costs flowing from this are more likely to be forecast than planned, though limits must be set.

In working out permitted expenditure for items in individual departmental budgets each item is expressed as a percentage of the major activity, say sales volume, and the permitted future budget expenditure determined as the same percentage of the planned new target. The common practice is to prepare the departmental and master budgets for a year and then to split them up into monthly budgets for ease of monitoring and comparison. Although calendar months are usually chosen it is suggested that four-week intervals are more suitable because they allow a fairer comparison of one month with another, each period being precisely the same duration as the others. Of course, in many circumstances seasonal fluctuations must also be taken into account when making month-to-month comparisons. In addition, in some activities the prime period of a year may be unsuitable and a shorter or longer time may be more informative: equally, the divisions may also be less or more than a month.

Administrative budgets cover all the items involved in operating the office function, the main ones being:

- Office salaries, including payments to part-time and temporary staff.

- Stationery and other office supplies. This includes minor pieces of equipment such as staplers.

- Telephone and postal charges.

- Lighting and heating.

- Rent and rates. If the premises are owned there will probably be an internal charge for occupation as determined by management on the advice of the management accountant.

- Cleaning.

- Maintenance and repair charges in respect of office machines and equipment.

The question of the purchase of new office machines or equipment is one to consider when preparing the administrative budget. Strictly speaking such expenditure should be included in a capital expenditure budget but items of comparatively low cost, such as small electronic calculators, are sometimes included in the administrative budget which is, of course, a revenue expenditure budget. This has the advantage of avoiding taking up the time of senior management for authority to make such low-cost capital purchases.

So far we have discussed fixed budgets – that is, budgets that assume the achievement of the planned main activity target, for example the planned sales volume. However, this is a rare occurrence: usually the actual attainment varies from this and so it is necessary to examine what

effect this has on budgets and on the administrative budget in particular. It follows that under-achievement results in lower expenditure and over-achievement in higher costs. It is thus necessary to formulate budgets to accommodate the variances in performance, these being termed flexible budgets.

Simply, a flexible budget is one that shows not only the expenditure for planned performance but also other levels of expenditure commensurate with other levels of performance. Stating the planned performance as 100 per cent, the budget may be extended to show levels of 70 per cent, 80 per cent, 90 per cent, 110 per cent, 120 per cent and so on, or other suitable intervals (see Figure 24.3).

Unfortunately this raises a problem because a straightforward decrease or increase in budgeted expenditure would be incorrect. The reason is simple. Certain items will reflect a decrease or an increase in cost in almost direct (but not precise) proportion to the percentage of achievement; such items as stationery and postage are examples. Other items will not fall or rise at all, such as rent and rates. The first are variable costs and the second fixed costs.

There is also a third category, semi-variable costs. These are a combination of both variable and fixed costs, a notable example being the telephone where the rent is fixed but call charges vary according to the amount of usage. Other such items include salaries, which will stay fixed for a considerable span between low and high activity and then change, and lighting and heating costs which tend to behave in the same way. Semi-variable costs are accommodated in a flexible budget by (a) modifying the percentage adjustments to take into account the element of fixed cost (as in telephone charges) and (b) estimating at what point a decrease or increase will occur (as with salaries).

Preparing budgets is, of course, only part of budgetary control. In order to effect actual control monitoring the actual expenditure and comparing it with the budget is necessary. This is done by requiring budget review statements to be prepared at monthly (or other regular) intervals showing actual and budgeted expenditure, indicating the variances that have occurred (see Figure 24.4). The variances can then be analysed and steps taken to correct the situation.

Consideration of budget review statements is normally done by a budgetary control committee specially formed for the purpose. It is important to recognise that the meetings of such committees are not to apportion blame for failure to conform to budget but to seek reasons and explanations so that remedial action can be taken. Nevertheless, the head of department – the office administrator in the case of the administrative budget – has to accept responsibility for performance.

Budgetary control has many advantages but, equally, has some limitations. The most important of these are as follows:

5.2. Advantages of budgeting

- It forces management to forecast and plan and so ensures a critical examination of the organisation’s activities. It also requires departmental heads to do the same in their own departments.

- Because the master budget is an amalgam of all departmental budgets and therefore will prove effective only if the* undertaking operates as a corporate whole, budgeting helps to encourage cooperation between sections and also helps to promote coordination throughout the organisation.

- Budgeting requires those responsible for drawing up budgets to look critically and analytically at all aspects of expenditure and cost, thereby tending to make those concerned economy-conscious.

- It provides a control that judges efficiency against a set target and so permits remedial action to be taken in good time where adverse results are indicated.

- It places responsibility for the proper utilisation of resources squarely where it belongs.

5.3. Disadvantages of budgeting

- Budgets can be too rigid, even where flexible budgets are used. This can often mean loss of purchasing opportunities.

- In some organisations there is no mechanism whereby a surplus on one budget can be transferred to another in deficit, even though this would be advantageous.

- In some cases budgets can stifle freedom of action and initiative. Less adventurous departmental heads will be satisfied with meeting their budget commitments; the more enterprising may be deterred from taking extra-budget action which could prove advantageous.

- Satisfaction at operating within budget may deter the search for further economies.

- In some quarters officers are encouraged to spend to the limit of their budgets through the fear that if they do not spend all that is permitted the budget ‘will be cut next year’.

- Budgeting and budgetary control can be expensive to operate and may not justify the costs involved when viewed from a purely financial point of view. Other benefits that cannot be quantified in monetary terms may, however, be adequate justification.

Budgeting and budgetary control can be useful and effective tools to control expenditure and to place responsibility for this firmly where it belongs. They are not, however, a substitute for the use of management expertise and initiative, neither are they an excuse for not using managerial judgement.

Source: Eyre E. C. (1989), Office Administration, Palgrave Macmillan.

good post.Ne’er knew this, thankyou for letting me know.