There was a time when performance was seen primarily in terms of individual motivation and performance. The focus has now shifted to emphasise performance of the organisation as a whole. While some performance variations are the result of individual differences, ultimate organisational performance can also be significantly affected by systems, processes, structures and culture. These are outside the control of the individual employee, but can be implemented and controlled to some extent by managers. The focus of this chapter is on the whole organisation and its performance, although it is inevitable that within this individual performance and team performance issues will play a part.

1. ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE ‘INITIATIVES’

The word ‘initiative’ may appear inappropriate, as approaches to improving organisational performance may be seen as long-term and permanent changes in the philosophy of the organisation and the way that it is managed. We use the word ‘initiative’ as this is usually the term used for packaging such ideas and presenting them to managers. These ‘initiatives’ generally involve a variety of organisational change measures, which may be structural, processual and/or cultural. Culture, in particular, has a high profile. How many times have you heard that organisations are attempting to develop a ‘quality culture’, a ‘learning culture’ or a ‘knowledge-centric culture’?

Many of these initiatives overlap; for example, similarities between business process re-engineering (BPR) and total quality management (TQM), and between TQM and learning organisations have been pointed out, although there are contradictions here too. Much current research and literature demonstrates the similarity between learning organisations and knowledge management. Similar concepts are used, such as ‘communities of practice’ (see, for example, Ortenblad 2001); and similar dilemmas are addressed, such as how to embed individual knowledge and learning into organisational systems and processes. Some of the same researchers investigate both areas, others link the two areas explicitly together (see, for example, Wang and Ahmed 2003; Easterby- Smith and Lyles 2005), conferences span both areas, for example the 2001 event in a series of conferences on organisational learning was entitled ‘Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management: New Directions’ (Vince et al. 2002), and in 2006 a special issue of the journal The Learning Organization focused on ‘Facilitating Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management’.

The term ‘initiative’ may also be misleading in that some organisations may display characteristics of these organisational performance strategies without ever consciously trying to implement such a strategy. A good example of this is provided by Jones (2001) who, in research on organisational twinning, claims that he might have ‘discovered’ a learning organisation. He suggests that members of the organisation may not have heard the term ‘learning organisation’, but the way that the organisation was led and managed provided the suitable conditions for a learning organisation to happen naturally. This is an interesting contrast to organisations which employ the rhetoric of a learning organisation but which in practice are quite different. In all of these performance initiatives, it is unfortunate that the way they have been applied does not always live up to the ideals that are promulgated.

2. LEARNING ORGANISATIONS

The interest in learning organisations has been stimulated by the need to be competitive, as learning is considered to be the only way of obtaining and keeping a competitive edge. Edmonson and Moingeon (1998, p. 9) put it very well when they say:

To remain viable in an environment characterized by uncertainty and change, organizations and individuals alike depend upon an ability to learn.

While the concept of organisational learning has been explored for some time, the concept of the learning organisation is a comparatively recent notion reflected in the literature since the late 1980s. Pedler et al. (1989) suggested that the concept of the learning organisation was a response to poor organisational performance. In other words they saw it as a way of overcoming

sluggishness, an excess of bureaucracy and over-control, of organisations as straitjackets frustrating the self-development efforts of individual members and failing to capitalise upon their potential.

In 1987 Pedler, Boydell and Burgoyne carried out a project entitled ‘Developing the Learning Company’ and interviewed staff in organisations which were pursuing learning company strategies. They asked why these strategies had been adopted, and found such reasons as the need to improve quality; the wish to become more people oriented in relation to both staff and customers; the need to encourage ‘active experimentation’ and generally to cope with competitive pressures in order to survive. They defined the learning organisation, which they identify as a ‘dream’ rather than a description of current practice, as:

an organisation which facilitates the learning of all its members and continually transforms itself.

There continues to be little empirical evidence of organisations that have transformed themselves like this, and in 1999 Sloman suggested that the concept of the learning organisation was in terminal decline. Part of the problem, he argues, is that there is such confusion over the concept and, as Stewart (2001) notes, a lack of tangible practices to implement. While Burgoyne (1999) and many others, such as Popper and Lipshitz (2000), concur with the extent of confusion, Burgoyne claims that there is still considerable interest in the idea from both organisations and academics, and that our understanding of the concept needs to be developed. He recognises that much of the early thinking about the learning organisation was naive, and suggests that, as the concept is developed, organisations will have more success with it. In particular, he describes the idea of becoming a learning organisation as one grand project, as ‘utopian and unrealistic’, and he recognises the value of a more incremental approach.

Easterby-Smith and Araujo (1999) note that a number of different disciplines have made a contribution to the debate on organisational learning and learning organisations, producing a plurality of perspectives. Part of the confusion, though, lies in the practices adopted by organisations under the banner of a learning organisation, rather than in the fundamental ideas. For example Yeo (2005) refers to nine different theoretical positions on the learning organisation. Academics and theorists may place different emphases on different aspects, but these are mutually supportive rather than conflicting. There is a common thread of a holistic approach and that organisational learning is greater than the sum of individual learning in the organisation. Different organisations appear to have been inspired by some aspects of this approach and, having adopted these, they see themselves as learning organisations. In essence they have taken some steps towards their goal, and have certainly improved the level of learning going on in the organisation, but have taken a partial rather than a holistic approach. A further confusion lies in the difference between the nature of organisational learning and the learning organisation, which we consider in the following section.

2.1. Organisational Learning and the Learning Organisation

The study of organisational learning is based on the detached observation of individual and collective learning processes in the organisation. The approach is critical and academic, and the focus is the nature and processes of learning, whereas Easterby- Smith and Araujo (1999) suggest that the study of learning organisations is focused on ‘normative models for creating change in the direction of improved learning processes’. Much of the research on learning organisations has been produced by consultants and organisations that are involved in the process. In other words the data come from an action learning perspective and are produced by interested parties, giving, inevitably, a positive spin to what is produced. This is not to say that the learning organisation perspective is devoid of theory. The study of learning organisations often focuses on organisational learning mechanisms, and these can be seen as a way of making the concept of organisational learning more concrete, and thus linking the two perspectives. Popper and Lipshitz (1998) describe organisational learning mechanisms as the structural and procedural arrangements that allow organisations to learn, in other words:

that is to collect, analyse, store, disseminate and use systematically information that is relevant to their and their members’ performance.

These issues are well reflected in Pedler et al.’s (1991) model of the learning organisation, which we will describe shortly. Easterby-Smith and Araujo (1999) argue that the literature on the learning organisation draws heavily on the concepts of organisational learning, from a utilitarian perspective, and there is some commonality in the literature, as Argyris and Schon (1996) suggest. It is generally agreed that there is a lack of critical research from both perspectives.

2.2. Organisational and individual learning

Although some pragmatic definitions of learning organisations centre on more and more individual learning, learning support and self-development, organisational learning is

more than just the sum of individual learning in the organisation. It is only when an individual’s learning has an impact on and interrelates with others that organisation members learn together and gradually begin to change the way things are done.

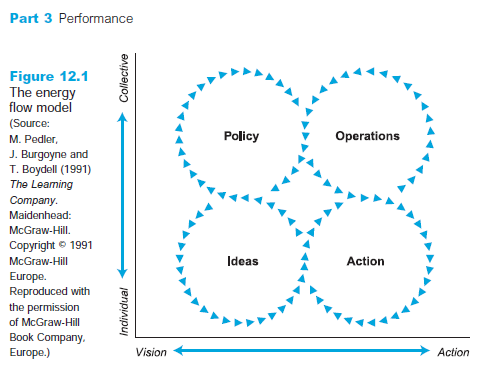

In this way mutual behaviour change is achieved which increases the collective competence, rather than just individual competence. Argyris and Schon (1978) see such learning as a change in the ‘theory in use’ (that is, the understanding, whether conscious or unconscious, that determines what we actually do) rather than merely a change in the ‘espoused’ theory (what we say we do). In other words the often unspoken rules of the organisation have changed. The question of how individual learning feeds into organisational learning and transformation, and how this is greater than the sum of individual learning, is only beginning to be addressed. Viewing the organisation as a process rather than an entity may offer some help here. Another perspective is that of viewing the organisation as a living organism. Pedler et al. (1991) make a useful start with their company energy flow model, shown in Figure 12.1.

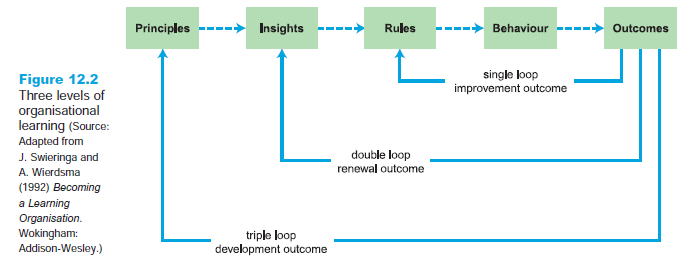

Argyris and Schon (1978) describe different levels, or loops, of organisational learning, which others have developed. These levels are:

- Level 1: Single loop learning. Learning about how we can do better, thus improving what we are currently doing. This is seen as learning at the operational level, or at the level of rules.

- Level 2: Double loop learning. A more fundamental level, which is concerned with ‘why’ questions in relation to what we are doing rather than with doing the same things better, that is, questioning whether we should be doing different things. This level is described as developing knowledge and understanding due to insights, and can result in strategic changes and renewal.

- Level 3: Triple loop learning. This level of learning is the hardest of all to achieve as it is focused on the purpose or principles of the organisation, challenging whether these are appropriate, and is sometimes described as learning at the level of will or being.

All these levels of organisational learning are connected, as shown in Figure 12.2.

2.3. What are the characteristics of learning organisations?

There are many different approaches to describing the characteristics of a learning organisation, and we shall briefly consider three of these. First, we look at the approach of Pedler et al. (1991), who identify 11 characteristics of a learning organisation, grouped into five general themes.

Strategy

Two characteristics within this theme are suggested, first that a learning approach to strategy should be taken. Strategy formation, implementation, evaluation and improvement are deliberately structured as learning experiences by using feedback loops. Second, participative policy making infers that this is shared with all in the organisation, and even further, that suppliers, customers and the total community have some involvement. The aim of the policy is to ‘delight customers’, and the differences of opinion and values that are revealed in the participative process are seen as productive tensions.

Looking in

Four characteristics are suggested within this theme – the first being informating which involves using technology to empower and inform employees, and to ensure information is made widely available. They note that such information should be used to provide understanding about what is going on in the company, and so stimulate learning, rather than being used to reward, punish or control. Second, there is formative accounting and control which involves designing accounting, budgeting and reporting systems to assist learning. Third, there is internal exchange which involves all internal units seeing themselves as customers and suppliers of each other. Fourth, they identify reward flexibility, which implies that the question of why some receive more money than others is a debate to be brought out into the open. They recommend that alternatives are discussed and tried out, but recognise that this is the most difficult of the 11 characteristics to put into practice.

Structures

Enabling structures suggest that roles are loosely structured in line with the needs of internal customers and suppliers, and in a way that allows for personal growth and experimentation. Internal boundaries can be flexible. For example, project groups and transient structures help to break down barriers between units, provide mechanisms for spreading new ideas and encourage the idea of change.

Looking out

Boundary workers as environmental scanners implies that part of the role of all workers in contact with suppliers, customers and neighbours of the organisation should be to participate in data collection. A second feature in this theme is inter-company learning, which entails joining with customers, suppliers and possibly competitors in training experiences, research and development and job exchanges. They also suggest that benchmarking can be used to learn from other companies.

Learning opportunities

First, a learning climate is important, that is, one that encourages experimentation and learning from experience, questioning current ideas, attitudes and actions and trying out new ideas. Mistakes are allowed because not all new ideas will work. There is a focus on continuous improvement, and the involvement of customers, suppliers and neighbours in experimentation is suggested. A learning climate suggests that feedback from others is continually requested, is made available and is acted upon. Second, self-development opportunities for all requires resources and facilities for self-development for employees at all levels in the organisation, and coaching, mentoring, peer support, counselling, feedback and so on must be available to support individuals in their learning.

Peter Senge (1990) takes a slightly different perspective. In his book about the art and practice of a learning organisation he identified five vital dimensions in building organisations which can learn, which he refers to as disciplines:

- Systems thinking. This is an understanding of the interrelatedness between things, seeing the whole rather than just a part and concentrating on processes. In terms of organisational actions it suggests that connections need to be constantly made and that there must be consideration of the implications that every action has elsewhere in the organisation.

- Personal mastery. This underlines the need for continuous development and individual self-development.

- Mental models. This is about the need to expose the ‘theories in use’ in the organisation. These can block change and the adoption of new ideas, and can only be confronted, challenged and changed if they are brought to the surface rather than remaining unconscious.

- Shared visions. This is expressing the need for a common purpose or vision which can inspire members of the organisation and break down barriers and mistrust. Senge argues that such a vision plus an accurate view of the present state results in a creative tension which is helpful for learning and change.

- Team learning. Teams are seen as important in that they are microcosms of the organisation, and the place where different views and perspectives come together, which Senge sees as a productive process.

Senge acknowledges that he presents a very positive vision of what organisations can do, and recognises that without the appropriate leadership this will not happen. He goes on to identify three critical leadership roles: designer, teacher and steward. As designer the leader needs to engage employees at all levels in designing the vision, core purpose and values of the organisation: design processes for strategic thinking and effective learning processes. As teacher the leader needs to help all organisation members gain more insight into the organisational reality, to coach, guide and facilitate, and help others bring their theories into use. As steward the leader needs to demonstrate a sense of personal commitment to the organisation’s mission and take responsibility for the impact of leadership on others.

Bob Garratt (1990) concentrates on the role that the directors of an organisation have in encouraging a learning organisation and in overcoming learning blocks. He suggests:

- the top team concentrate on strategy and policy and hold back from day-to-day operational issues;

- thinking time is needed for the top team to relate changes in the external environment to the internal working of the organisation;

- the creation of a top team, involving the development and deployment of the strengths of each member;

- the delegation of problem solving to staff close to the operation;

- acceptance that learning occurs at all levels of the organisation, and that directors need to create a climate where this learning flows freely.

Clearly, a learning organisation is not something that can be developed overnight and has to be viewed as a long-term strategy.

Easterby-Smith (1990) makes some key points about encouraging experimentation in organisations in relation to flexible structures, information, people and reward. We have discussed flexibility and information in some detail. In respect of people he argues that organisations will seek to select those who are similar to current organisation members. The problem here is that such a strategy, in reinforcing homogeneity and reducing diversity, restrains the production of innovative and creative ideas. He sees diversity as a positive stimulant and concludes that organisations should therefore select some employees who would not normally fit their criteria, and especially those who would be likely to experiment and be able to tolerate ambiguity. In relation to the reward system he notes the need to reinforce rather than punish risk taking and innovation.

Critique

The initial idealism of the learning organisation concept has been tempered by experiences, and more pragmatic material is gradually being developed. Popper and Lipshitz (2000) have identified four conditions under which organisational learning is likely to be productive. These are in situations where there is:

- Valid information – that is, complete, undistorted and verifiable information.

- Transparency – where individuals are prepared to hold themselves open to inspection in order to receive valid feedback. This reduces self-deception, and helps to resist pressures to distort information.

- Issues orientation rather than a personal orientation – that is, where information is judged on its merits and relevance to the issue at hand, rather than on the status or attributes of the individual who provides the information.

- Accountability – that is, ‘holding oneself responsible for one’s own actions and their consequences and for learning from these consequences’.

In a different approach Burgoyne (1999) provides a list of nine things that need to happen for continuous learning to become a reality.

There remains a wide range of concerns regarding the concept of the learning organisation. Hawkins (1994) notes the evangelistic fervour with which learning organisations and total quality management (TQM) are recommended to the uninitiated and fears that the commercialisation of these ideas means that they become superficial. He argues that an assumption may be made that all learning is good whatever is being learned, whereas the value of learning lies in where it is taking us and, as Stewart (2001) points out, learning is neither objective nor neutral. Learning should be seen as the means rather than the end in itself. Learning to be more efficient at what is being done does not necessarily make one more effective; it depends on the appropriateness of the activity itself. It is not surprising therefore that there is a lack of evidence linking learning organisation strategies with financial performance (see, for example, Sonsino 2002).

Nor does the literature cover adequately the barriers to becoming a learning organisation – for example, the role of politics within the organisation. If learning requires sharing of information, and information is power, then how can individuals be encouraged to let go of the power they have? There has also been a lack of attention to emotion, ethics and human irrationality. Harris (2002), for example, demonstrates how the potential for learning in her retail bank case studies was constrained by the

overwhelming desire to maintain continuity in the organisation. Other qualitative work concentrating on employee perceptions has found that some employees exclude themselves from being part of a learning organisation, apparently feeling no need to develop further (Dymock and McCarthy 2006).

In particular, both Senge (1990) and Garratt (1990) have high expectations of the leaders of organisations. To what extent are these expectations realistic, and how might they be achieved? The literature of learning organisations has a clear unitarist perspective – the question of whether employees desire to be involved in or united by a vision of the organisation needs to be addressed. The question of willing participation was also raised by Harris when she found that contractors were unwilling to share their learning when leaving the organisation, even though this expectation was built into their contracts. For a useful critique of the assumptions behind learning organisations, see Coopey (1995). In addition, the full complexity of the ideas implicit in the words ‘learning organisation’ requires more explanation.

The problems in implementing learning organisation prescriptions has led Sun and Scott (2003) to suggest that attention needs to refocus on organisational learning in order really to understand how individual learning can be transformed into collective learning, and they suggest some useful ways forward. An alternative development is that of the ‘living company’ which extends the learning organisation concept, and this is the subject of Case 12.1 on this book’s companion website, www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington. Another focus has been the more recent attention to knowledge management which is generally presented in a more practical/applicable manner, and yet as we have previously suggested has some similar foundations to the learning organisation.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Some truly select articles on this internet site, saved to favorites.