In this section we examine a wide variety of factors that influence network design decisions in supply chains.

1. Strategic Factors

A firm’s competitive strategy has a significant impact on network design decisions within the supply chain. Firms that focus on cost leadership tend to find the lowest cost location for their manufacturing facilities, even if that means locating far from the markets they serve. Electronic manufacturing service providers such as Foxconn and Flextronics have been successful in providing low-cost electronics assembly by locating their factories in low-cost countries such as China. In contrast, firms that focus on responsiveness tend to locate facilities closer to the market and may select a high-cost location if this choice allows the firm to react quickly to changing market needs. Zara, the Spanish apparel manufacturer, has a large fraction of its production capacity in Portugal and Spain despite the higher cost there. The local capacity allows the company to respond quickly to changing fashion trends. This responsiveness has allowed Zara to become one of the largest apparel retailers in the world.

Convenience store chains aim to provide easy access to customers as part of their competitive strategy. Convenience store networks thus include many stores that cover an area, with each store being relatively small. In contrast, discount stores such as Sam’s Club or Costco use a competitive strategy that focuses on providing low prices. Thus, their networks have large stores, and customers often have to travel many miles to get to one. The geographic area covered by one Sam’s Club store may include dozens of convenience stores.

Global supply chain networks can best support their strategic objectives with facilities in different countries playing different roles. For example, Zara has production facilities in Europe as well as Asia. Its production facilities in Asia focus on low cost and produce primarily standardized, low-value products that sell in large amounts. The European facilities focus on being responsive and produce primarily trendy designs whose demand is unpredictable. This combination of facilities allows Zara to produce a wide variety of products in the most profitable manner.

2. Technological Factors

Characteristics of available production technologies have a significant impact on network design decisions. If production technology displays significant economies of scale, a few high-capacity locations are most effective. This is the case in the manufacture of computer chips, for which factories require a large investment and the output is relatively inexpensive to transport. As a result, most semiconductor companies build a few high-capacity facilities.

In contrast, if facilities have lower fixed costs, many local facilities are preferred because this helps lower transportation costs. For example, bottling plants for Coca-Cola do not have a high fixed cost. To reduce transportation costs, Coca-Cola sets up many bottling plants all over the world, each serving its local market.

3. Macroeconomic Factors

Macroeconomic factors include taxes, tariffs, exchange rates, and shipping costs that are not internal to an individual firm. As global trade has increased, macroeconomic factors have had a significant influence on the success or failure of supply chain networks. Thus, it is imperative that firms take these factors into account when making network design decisions.

TARIFFS AND TAX INCENTIVES Tariffs refer to any duties that must be paid when products and/or equipment are moved across international, state, or city boundaries. Tariffs have a strong influence on location decisions within a supply chain. If a country has high tariffs, companies either do not serve the local market or set up manufacturing plants within the country to save on duties. High tariffs lead to more production locations within a supply chain network, with each location having a lower allocated capacity. As tariffs have decreased with the World Trade Organization and regional agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the European Union, and Mercosur (South America), global firms have consolidated their global production and distribution facilities.

Tax incentives are a reduction in tariffs or taxes that countries, states, and cities often provide to encourage firms to locate their facilities in specific areas. Many countries vary incentives from city to city to encourage investments in areas with lower economic development. Such incentives are often a key factor in the final location decision for many plants. BMW, for instance, built its U.S. factory in Spartanburg, South Carolina, mainly because of the tax incentives offered by that state.

Developing countries often create free trade zones in which duties and tariffs are relaxed as long as production is used primarily for export. This creates a strong incentive for global firms to set up plants in these countries to be able to exploit their low labor costs. In China, for example, the establishment of a free trade zone near Guangzhou led to many global firms locating facilities there in the 1990s.

A large number of developing countries also provide additional tax incentives based on training, meals, transportation, and other facilities offered to the workforce. Tariffs may also vary based on the product’s level of technology. China, for example, waived tariffs entirely for high- tech products in an effort to encourage companies to locate there and bring in state-of-the-art technology. Motorola located a large chip manufacturing plant in China to take advantage of the reduced tariffs and other incentives available to high-tech products.

Many countries also place minimum requirements on local content and limits on imports to help develop local manufacturers. Such policies lead global companies to set up local facilities and source from local suppliers. For example, the Spanish company Gamesa was a dominant supplier of wind turbines to China, owning about a third of the market share in 2005. In that year, China declared that wind farms had to buy equipment in which at least 70 percent of content was local. This forced players such as Gamesa and GE, which wanted a piece of the Chinese market, to train local suppliers and source from them. In 2009, China revoked the local content requirements. By then, Chinese suppliers had sufficiently large scale to achieve some of the lowest costs in the world. These suppliers also sold parts to Gamesa’s Chinese competitors, which developed into dominant global players.

EXCHANGE-RATE AND DEMAND RISK Fluctuations in exchange rates are common and have a significant impact on the profits of any supply chain serving global markets. For example, the dollar fluctuated between a high of 124 yen in 2007 and a low of 81 yen in 2010, then back to over 100 yen in 2014. A firm that sells its product in the United States with production in Japan is exposed to the risk of appreciation of the yen. The cost of production is incurred in yen, whereas revenues are obtained in dollars. Thus, an increase in the value of the yen increases the production cost in dollars, decreasing the firm’s profits. In the 1980s, many Japanese manufacturers faced this problem when the yen appreciated in value, because most of their production capacity was located in Japan. The appreciation of the yen decreased their revenues (in terms of yen) from large overseas markets, and they saw their profits decline. Most Japanese manufacturers responded by building production facilities all over the world. The dollar fluctuated between 0.63 and 1.15 euros between 2002 and 2008, dropping to 0.63 euro in July 2008. The drop in the dollar was particularly negative for European automakers such as Daimler, BMW, and Porsche, which export many vehicles to the United States. It was reported that every one-cent rise in the euro cost BMW and Mercedes roughly $75 million each per year.

Exchange-rate risks may be handled using financial instruments that limit, or hedge against, the loss due to fluctuations. Suitably designed supply chain networks, however, offer the opportunity to take advantage of exchange-rate fluctuations and increase profits. An effective way to do this is to build some overcapacity into the network and make the capacity flexible so it can be used to supply different markets. This flexibility allows the firm to react to exchange-rate fluctuations by altering production flows within the supply chain to maximize profits.

Companies must also take into account fluctuations in demand caused by changes in the economies of different countries. For example, 2009 was a year in which the economies of the United States and Western Europe shrank (real GDP in the United States decreased by 2.4 percent),

while that in China grew by more than 8 percent and in India by about 7 percent. During this period, global companies with presence in China and India and the flexibility to divert resources from shrinking to growing markets did much better than those that did not have either presence in these markets or the flexibility. As the economies of Brazil, China, and India continue to grow, global supply chains will have to build more local presence in these countries along with the flexibility to serve multiple markets.

FREIGHT AND FUEL COSTS Fluctuations in freight and fuel costs have a significant impact on the profits of any global supply chain. For example, in 2010 alone, the Baltic Dry Index, which measures the cost to transport raw materials such as metals, grains, and fossil fuels, peaked at 4,187 in May and hit a low of 1,709 in July. Crude oil prices were as low as about $31 per barrel in February 2009 and increased to about $90 per barrel by December 2010. It can be difficult to deal with this extent of price fluctuation even with supply chain flexibility. Such fluctuations are best dealt with by hedging prices on commodity markets or signing suitable long-term contracts. During the first decade of the twenty-first century, for example, a significant fraction of Southwest Airlines’ profits were attributed to fuel hedges it had purchased at good prices.

When designing supply chain networks, companies must account for fluctuations in exchange rates, demand, and freight and fuel costs.

Political Factors

The political stability of the country under consideration plays a significant role in location choice. Companies prefer to locate facilities in politically stable countries where the rules of commerce and ownership are well defined. While political risk is hard to quantify, there are some indices, such as the Global Political Risk Index (GPRI), that companies can use when investing in emerging markets. The GPRI is evaluated by a consulting firm (Eurasia Group) and aims to measure the capacity of a country to withstand shocks or crises along four categories: government, society, security, and economy.

4. Infrastructure Factors

The availability of good infrastructure is an important prerequisite to locating a facility in a given area. Poor infrastructure adds to the cost of doing business from a given location. In the 1990s, global companies located their factories in China near Shanghai, Tianjin, or Guangzhou—even though these locations did not have the lowest labor or land costs—because these locations had good infrastructure. Key infrastructure elements to be considered during network design include availability of sites and labor, proximity to transportation terminals, rail service, proximity to airports and seaports, highway access, congestion, and local utilities.

5. Competitive Factors

Companies must consider competitors’ strategy, size, and location when designing their supply chain networks. A fundamental decision firms make is whether to locate their facilities close to or far from competitors. The form of competition and factors such as raw material or labor availability influence this decision.

positive externalities between firms Positive externalities occur when the collocation of multiple firms benefits all of them. Positive externalities lead to competitors locating close to each other. For example, retail stores tend to locate close to each other because doing so increases overall demand, thus benefiting all parties. By locating together in a mall, competing retail stores make it more convenient for customers, who need drive to only one location to find everything they are looking for. This increases the total number of customers who visit the mall, increasing demand for all stores located there.

Another example of positive externality occurs when the presence of a competitor leads to the development of appropriate infrastructure in a developing area. In India, Suzuki was the first foreign auto manufacturer to set up a manufacturing facility. The company went to considerable effort and built a local supplier network. Given the well-established supplier base in India, Suzuki’s competitors have also built assembly plants there, because they now find it more effective to build cars in India rather than import them to the country.

LOCATING TO SPLIT THE MARKET When there are no positive externalities, firms locate to be able to capture the largest possible share of the market. A simple model first proposed by Hotelling explains the issues behind this decision (Tirole, 1997).

When firms do not control price but compete on distance from the customer, they can maximize market share by locating close to each other and splitting the market. Consider a situation in which customers are uniformly located along the line segment between 0 and 1 and two firms compete based on their distance from the customer as shown in Figure 5-1. A customer goes to the closer firm and customers who are equidistant from the two firms are evenly split between them.

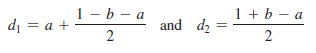

If total demand is 1, Firm 1 locates at point a, and Firm 2 locates at point 1- b, the demand at the two firms, d1 and d2, is given by

Both firms maximize their market share if they move closer to each other and locate at a = b = 1>2.

Observe that when both firms locate in the middle of the line segment (a = b = 1>2), the average distance that customers have to travel is 1 >4. If one firm locates at 1 >4 and the other at 3>4, the average distance customers have to travel drops to 1>8 (customers between 0 and 1>2 come to Firm 1, located at 1>4, whereas customers between 1>2 and 1 come to Firm 2, located

at 3>4). This set of locations, however, is not an equilibrium because it gives both firms an incentive to try to increase market share by moving to the middle (closer to 1 >2). The result of competition is for both firms to locate close together, even though doing so increases the average distance to the customer.

If the firms compete on price and the customer incurs the transportation cost, it may be optimal for the two firms to locate as far apart as possible, with Firm 1 locating at 0 and Firm 2 locating at 1. Locating far from each other minimizes price competition and helps the firms split the market and maximize profits.

6. Customer Response Time and Local Presence

Firms that target customers who value a short response time must locate close to them. Customers are unlikely to come to a convenience store if they have to travel a long distance to get there. It is thus best for a convenience store chain to have many stores distributed in an area so most people have a convenience store close to them. In contrast, customers shop for larger quantity of goods at supermarkets and are willing to travel longer distances to get to one. Thus, supermarket chains tend to have stores that are larger than convenience stores and not as densely distributed. Most towns have fewer supermarkets than convenience stores. Discounters such as Sam’s Club target customers who are even less time sensitive. These stores are even larger than supermarkets and there are fewer of them in an area. W.W. Grainger uses about 400 facilities all over the United States to provide same-day delivery of maintenance and repair supplies to many of its customers. McMaster-Carr, a competitor, targets customers who are willing to wait for next-day delivery. McMaster-Carr has only five facilities throughout the United States and is able to provide next-day delivery to a large number of customers.

If a firm is delivering its product to customers, use of a rapid means of transportation allows it to build fewer facilities and still provide a short response time. This option, however, increases transportation cost. Moreover, there are many situations in which the presence of a facility close to a customer is important. A coffee shop is likely to attract customers who live or work nearby. No faster mode of transport can serve as a substitute and be used to attract customers who are far away from the coffee shop.

7. Logistics and Facility Costs

Logistics and facility costs incurred within a supply chain change as the number of facilities, their location, and capacity allocation change. Companies must consider inventory, transportation, and facility costs when designing their supply chain networks.

Inventory and facility costs increase as the number of facilities in a supply chain increases. Transportation costs decrease as the number of facilities increases. If the number of facilities increases to the point at which inbound economies of scale are lost, then transportation costs increase. For example, with few facilities, Amazon has lower inventory and facility costs than Barnes & Noble, which has hundreds of stores. Barnes & Noble, however, has lower transportation costs.

The supply chain network design is also influenced by the transformation occurring at each facility. When there is a significant reduction in material weight or volume as a result of processing, it may be better to locate facilities closer to the supply source rather than the customer. For example, when iron ore is processed to make steel, the amount of output is a small fraction of the amount of ore used. Locating the steel factory close to the supply source is preferred because it reduces the distance that the large quantity of ore has to travel.

Total logistics costs are the sum of the inventory, transportation, and facility costs. The facilities in a supply chain network should at least equal the number that minimizes total logistics cost. A firm may increase the number of facilities beyond this point to improve the response time to its customers. This decision is justified if the revenue increase from improved response outweighs the increased cost from additional facilities.

In the next section we discuss a framework for making network design decisions.

Source: Chopra Sunil, Meindl Peter (2014), Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, Pearson; 6th edition.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me and my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research on this. We got a grab a book from our local library but I think I learned more from this post. I am very glad to see such fantastic info being shared freely out there.