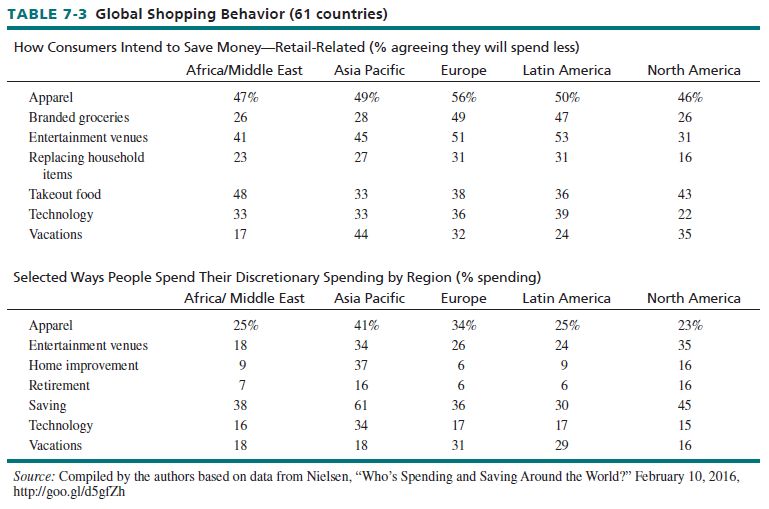

In this section, we look at people’s attitudes toward shopping, where they shop, and the way in which they make purchase decisions. The top of Table 7-3 shows how shoppers around the world say they would change their retail behavior if they needed to reduce their spending; the bottom of the table indicates how global shoppers say they would alter their behavior if they have extra money to spend. Notice the differences among people living in different regions of the world.

1. Attitudes toward Shopping

Research has been done on people’s attitudes and motivations toward shopping. Such attitudes have a big impact on the ways in which people act in a retail setting. Retailers must strive to turn around some negative perceptions that now exist. We will highlight some research findings here.

SHOPPING ENJOYMENT Generally, people today do not enjoy shopping as much as they did before. However, some consumers enjoy shopping and consider it a pleasant experience. Consumers who seek relaxation and/or fun while shopping may prefer goods and services associated with higher prices, such as national brands and popular department stores. Although research on the relationship between shopping enjoyment, time spent, and size in the context of physical stores has been ambiguous, perceived shopping enjoyment has a significant positive effect on Web visit duration and purchase conversion.

So, what does stimulate a pleasurable shopping experience—a challenge that retailers must address to increase share of wallet and loyalty? Customers derive shopping enjoyment from their assessment of accessibility and in-store atmospherics that include music, lighting, store design, window displays, visual merchandising, and personnel. Drivers of shopping enjoyment differ by gender—men seek fast, efficient shopping, whereas women often prefer a relaxing atmosphere. In the online retailing environment, use of 3D virtual models, close-up pictures, zoom-in functions, and mix-and-match capabilities enhance the online shopping experience.13

ATTITUDES TOWARD SHOPPING TIME Time pressure and emergency purchase situations are important situational influences that impact retail shopping enjoyment and outcomes. Demographic changes, including the high proportion of dual-income households and the increase in the number of earners managing multiple jobs due to wage stagnation, have contributed to chronic time pressure. Research shows that shoppers are task-oriented, under time pressure, and likely to rely on economic cues such as unit-price data in making product selections.14 Further, retail assortment size and complexity can create perceived time pressure when shopping online or in-store. Retailers have often increased their assortments to keep up with changing customer trends and face the challenging tradeoff of whether “more is better” or “less is better” in terms of assortments. Thus, retailers should not only invest more in store atmospherics (such as music, color, lighting, smell, and visual merchandising) but also pay equal attention to the efficiency of store location, parking, and sales personnel assistance that may reduce shoppers’ chronic time pressure.”15

CAUTIOUS OPTIMISM AND DISPARITY IN WEALTH EFFECT There is a disparity in wealth across income tiers. Higher-income consumers are more likely to own stocks; and when their investments gain, they spend more at luxury retailers. Lower-income consumers are less likely to own stocks and the lack of wage growth means that they haven’t seen any improvement in their financial standing over the last several years. For them, memories of the recession linger, which has led to more cautionary spending habits and the propensity to save the extra cash from lower mortgage and energy costs. These consumers have traded down to less expensive brands and shop more at discount stores to secure the most value for their dollar; sometimes, they postpone or forgo discretionary big-ticket items. This has led to bifurcated retailing, with high-end and low-end retailers doing better than middle-of-the road retailers.16

WHY PEOPLE BUY OR DO NOT BUY ON A SHOPPING TRIP It is critical for retailers to determine why shoppers leave without making a purchase. Some consumers at online stores place items in their virtual shopping carts but later abandon them, which can lead to lost sales for high-demand, fast-fashion products.17 Research on shopper behavior indicates that shopping goals determine the consumer’s retail journey through both physical and online stores. Shopping goals differ

across consumers and across shopping occasions for each consumer based on the complexity of product purchase, as well as the time horizon within which the purchase decision needs to be made. On some shopping trips, consumers might conduct a goal-directed search to browse and collect information; whereas on other occasions, they might compare items and complete the purchase. On yet other shopping occasions, they might just enjoy experiential browsing or window shopping. Consumers’ shopping goals may also change in response to the shopping environment such as product presentations or demonstrations, sensory stimuli such as smell or music,18 prices, promotions, salesperson interaction, and the behavior of other shoppers in the store.

ATTITUDES BY MARKET SEGMENT There is considerable academic and commercial research on shopper segmentation. Researchers have segmented shoppers in terms of consumer characteristics (geo-demographics and psychographics), purchase quantity/variety/frequency, promotion sensitivity and usage, search behavior, shopping values, multichannel usage behavior, and post-purchase behavior.19 One recent study, examining “smart” shopping activities, identified three smart grocery shopper segments: involved, spontaneous, and apathetic.

Involved shoppers are apt to be Baby Boomers and prioritize saving time and effort, be attracted by retailers that provide good product assortment and price-saving opportunities in the form of sales, coupons, or bulk pricing. They spend more time planning stores to visit, but engage in minimal information search on products and brand alternatives, hence in-store purchase activities of hedonic value (sampling, in-store cafe) are essential. Spontaneous shoppers are primarily Baby Boomers and least likely to engage in pre-purchase planning and information search, but they care more about saving time and effort than apathetic shoppers. The majority of apathetic shoppers are Generation Xers, those less likely to be time conscious and more likely to have a low marketplace knowledge. This group holds the inherent belief that they are smart shoppers. Although they are most likely to engage in online pre-purchase information search than the other segments, they are price-conscious but do not plan or respond to in-store promotional stimuli.

ATTITUDES TOWARD PRIVATE BRANDS Many consumers believe private (retailer) brands are as good as or better than manufacturer brands. Private label dollar-based market shares exceed one-sixth of U.S. and Canadian revenues. Although these market shares are less than in Western Europe (where private-label sales are over 30 percent), the majority of American and Canadian consumers have positive perceptions of private-label goods: 75 percent of Americans and 73 percent of Canadians view private-label products as a good alternative to national brands; 74 percent of Americans and 66 percent of Canadians state they are a good value; and 67 percent of Americans and 61 percent of Canadians feel they are at parity with national brands on quality.20

2. Where People Shop

Consumer patronage differs sharply by type of retailer. Thus, it is vital for firms to recognize the venues where consumers are most likely to shop and plan accordingly.

Many consumers do cross-shopping, whereby they (1) shop for a product category at more than one retail format during the year or (2) visit multiple retailers on one shopping trip. The first scenario occurs because these consumers feel comfortable shopping at different formats during the year, their goals vary by occasion (they may want bargains on everyday clothes and fashionable items for weekend wear), they shop wherever sales are offered, and they have a favorite format for themselves and another one for other household members. Visiting multiple outlets on one trip occurs because consumers want to save travel and shopping time. The increased use of retail apps on mobile phones during in-store shopping induces more cross-shopping as retailers compete to deploy geo-targeted promotions that activate at competitors’ stores, which attracts people to visit competitors’ stores. According to a survey by the National Retail Federation, the most planned activity for smartphone users is researching products and comparing prices (38 percent of smartphone owners). The second most planned activity on smartphones (28 percent of smartphone owners) is looking up information, such as location, store hours, and directions.21

Here are some cross-shopping examples:

Here are some cross-shopping examples:

- Some supermarket customers also regularly buy items carried by the supermarket at convenience stores, full-line department stores, drugstores, and specialty food stores.

- Some department-store customers also regularly buy items carried by the department store at factory outlets and full-line discount stores.

- The majority of Web shoppers also buy from catalog retailers, mass merchants, apparel chains, and/or department stores.

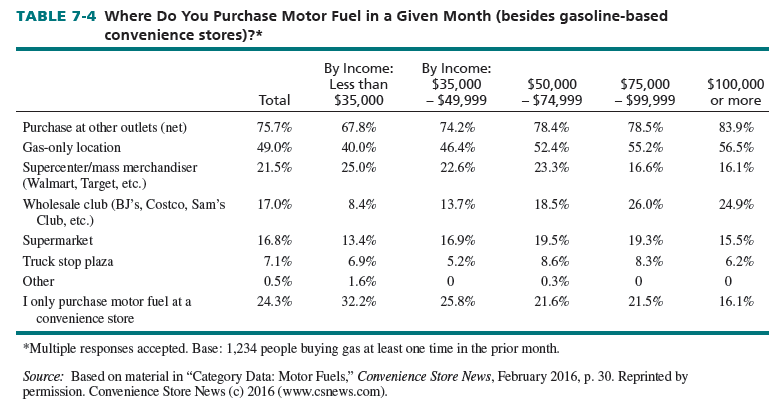

- Cross-shopping is high for apparel, home furnishings, shoes, sporting goods, personal-care items, and motor fuel. Table 7-4 shows cross-shopping for motor fuel purchases.

3. The Consumer Decision Process

Besides identifying target market traits, a retailer should know how people make decisions. This requires familiarity with consumer behavior, which is the process by which people determine whether, what, when, where, how, from whom, and how often to purchase goods and services. Such behavior is influenced by a person’s background and traits.

The decision process must be grasped from two different perspectives: (1) what good or service the consumer is thinking about buying and (2) where the consumer is going to buy that item (if the person opts to buy). A consumer can make these decisions separately or jointly. If made jointly, she or he relies on the retailer for support (information, assortments, and informed sales personnel) over the full decision process. If the decisions are made independently—what to buy versus where to buy—the person gathers information and advice before visiting a retailer and views the retailer merely as a place to buy (and probably more interchangeable with other firms).

In choosing whether or not to buy a given item (what), the consumer considers features, durability, distinctiveness, value, ease of use, and so on. In choosing the retailer to patronize for that item (where), the consumer considers location, assortment, credit availability, sales help, hours, customer service, and so on. Thus, the manufacturer and retailer have distinct challenges: The manufacturer wants people to buy its brand what) at any location carrying it (where). The retailer wants people to buy the product, (http://publications.usa.gov/ not necessarily the manufacturer’s brand (what), at its store or nonstore location (where).

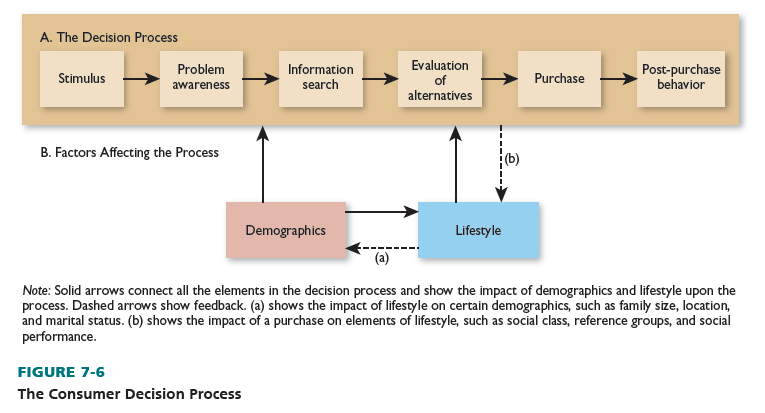

The consumer decision process has two parts: the process itself and the factors affecting the process. There are six steps in the process: stimulus, problem awareness, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase, and post-purchase behavior. The consumer’s demographics and lifestyle affect the process. The complete process is shown in Figure 7-6.

The best retailers assist shoppers at each stage in the process: stimulus (online ads), problem awareness (stocking new models), information search (point-of-sale displays and good salespeople), evaluation of alternatives (noticeable differences among products), purchase (acceptance of credit cards), and post-purchase behavior (extended warranties and money-back returns). The greater the role a retailer assumes in the decision process, the more loyal the consumer will be.

Each time a person buys a good or service, he or she goes through a decision process. In some cases, all six steps in the process are utilized; in others, only a few steps are employed. For example, a consumer who has previously and satisfactorily bought luggage at a local store may not use the same extensive process as one who has never bought luggage.

The decision process outlined in Figure 7-6 assumes that the end result is a purchase. However, at any point, a potential customer may decide not to buy; the process then stops. A good or service may be unneeded, unsatisfactory, or too expensive. Before discussing the ways in which retail consumers use the decision process, we explain the entire process.

Stimulus. A stimulus is a cue (social or commercial) or a drive (physical) meant to motivate or arouse a person to act. When a person talks with friends, fellow employees, and others, a social cue is received. The special attribute of a social cue is that it involves an interpersonal, noncommercial source. A commercial cue is a message sponsored by a retailer or some other seller. Ads, sales pitches, and store displays are commercial stimuli. Such cues may not be regarded as highly as social ones by consumers because they are seller-controlled. A third type of stimulus is a physical drive. It occurs when one or more of a person’s physical senses are affected. Hunger, thirst, cold, heat, pain, or fear could cause a physical drive. A potential consumer may be exposed to any or all three types of stimuli. If aroused (motivated), he or she goes to the next step in the process. If a person is not sufficiently aroused, the stimulus is ignored—terminating the process for the given good or service under consideration may solve a problem of shortage or unfulfilled desire. It may be hard to learn why a person is motivated to move from stimulus to problem awareness. Many people shop with the same retailer or buy the same good or service for different reasons; they may not know their own motivation, and they may not tell a retailer their reasons for shopping there or buying a certain item.

Recognition of shortage occurs when a person discovers a good or service should be repurchased. A good could wear down beyond repair, or the person might run out of an item such as milk. Service may be necessary if a good (such as a car) requires a repair. Recognition of unfulfilled desire takes place when a person becomes aware of a good or service that has not been bought before or a retailer that has not been patronized before. An item (such as contact lenses) may improve a person’s lifestyle or self-image in an untried manner, or it may offer new features (such as a voice-activated laptop). People are more hesitant to act on unfulfilled desires. Risks and benefits may be tougher to see. When a person becomes aware of a shortage or an unfulfilled desire, he or she acts only if it is a problem worth solving. Otherwise, the process ends.

Information search. If problem awareness merits further thought, information is sought. An information search has two parts: (1) determining the alternatives that will solve the problem at hand (and where they can be bought) and (2) ascertaining the characteristics of each alternative.

First, the person compiles a list of goods or services that address the shortage or desire being considered. This list does not have to be formal. It may be a group of alternatives the person thinks about. A person with a lot of purchase experience normally uses an internal memory search to determine the goods or services—and retailers—that are satisfactory. A person with little purchase experience often uses an external search to develop a list of alternatives and retailers. This search can involve commercial sources such as retail salespeople, noncommercial sources such as Consumer Reports, and social sources such as friends. Second, the person gathers information about each alternative’s attributes. An experienced shopper searches his or her memory for the attributes (pros and cons) of each alternative. A consumer with little experience or a lot of uncertainty searches externally for information.

The extent of an information search depends, in part, on the consumer’s perceived risk regarding a specific good or service. Risk varies among individuals and by situation. For some, it is inconsequential; for others, it is important. The retailer’s role is to provide enough information for a shopper to feel comfortable in making decisions, thus reducing perceived risk. Point-of-purchase ads, product displays, and knowledgeable sales personnel can provide consumers with the information they need.

When the consumer’s search for information is completed, she or he must decide whether a current shortage or unfulfilled desire can be met by any of the alternatives. If one or more are satisfactory, the consumer moves to the next step in the decision process. The consumer stops the process if no satisfactory goods or services are found.

Evaluation of alternatives. Next, a person selects one option. This is easy if one alternative is better on all features. An item with great quality and a low price is a certain pick over expensive, average-quality ones. Yet, a choice may not be that simple, and the person then does an evaluation of alternatives before making a decision. If two or more options seem attractive, the person sets the criteria to evaluate and their importance. Alternatives are ranked and a choice is made.

The criteria for a decision are those good or service attributes considered relevant. They may include price, quality, fit, durability, and so on. The person sets standards for these characteristics and rates each alternative according to its ability to meet them. The importance of each criterion is also set, and attributes are often of differing importance to each person. One person may consider price as most important while another places more weight on quality and durability.

At this point, the person ranks alternatives from most favorite to least favorite and selects one. Sometimes, it is hard to rate attributes because they are technical, intangible, new, or poorly labeled. When this occurs, shoppers often use price, brand name, or store name to indicate quality and choose based on this criterion. After a person ranks alternatives, he or she chooses the most satisfactory one. In situations where no alternative is adequate, a decision not to buy is made.

Purchase act. A person is now ready for the purchase act—an exchange of money or a promise to pay for the ownership or use of a good or service. Important decisions are still made in this step. For a retailer, the purchase act may be the most crucial aspect of the decision process because the consumer is mainly concerned with three factors, as highlighted in Figure 7-7:

- Place of purchase: This may be a store or a nonstore location. Many more items are bought at stores than through nonstore retailing, although the latter method is growing quickly. The place of purchase is evaluated in the same way as the good or the service: alternatives are listed, their traits are defined, and they are ranked. The most desirable place is then chosen.

Criteria for selecting a store retailer include store location, store layout, service, sales help, store image, and prices. Criteria for selecting a nonstore retailer include image, service, prices, hours, interactivity, and convenience. A consumer will shop with the firm that has the best combination of criteria, as defined by that consumer.

- Purchase terms: These include the price and method of payment. Price is the dollar amount a person must pay to achieve the ownership or use of a good or service. Method of payment is the way the price may be paid (cash, short-term credit, long-term credit).

- Availability: This relates to stock on hand and delivery. Stock on hand is the amount of an item that a place of purchase has in stock. Delivery is the time span between placing an order and receiving an item and the ease with which an item is transported to its place of use.

If a person is pleased with all aspects of the purchase act, the good or service is bought. If there is dissatisfaction with the place of purchase, the terms of purchase, or availability, the consumer may not buy, although she or he may be satisfied with the item itself.

Post-purchase behavior. After buying a good or service, a consumer may engage in postpurchase behavior, which falls into either of two categories: further purchases or re-evaluation. Sometimes, buying one item leads to further purchases and decision making continues until the last purchase. A car purchase leads to insurance; a retailer using scrambled merchandising may stimulate a shopper to further purchase after the primary good or service is bought.

A person may also re-evaluate a purchase. Is performance as promised? Do actual attributes match the expectations the consumer had? Has the retailer acted as expected? Satisfaction typically leads to contentment, a repurchase when a good or service wears out, and positive ratings to friends. Dissatisfaction may lead to unhappiness, brand or store switching, and unfavorable conversations with friends and negative online postings. The latter situation (dissatisfaction) may result from cognitive dissonance—doubt that the correct decision has been made. A consumer may regret that the purchase was made at all or may wish that another choice had been made. To overcome cognitive dissonance and dissatisfaction, the retailer must realize that the decision process does not end with a purchase. After-care (by phone, a service visit, or E-mail) may be as important as anything a retailer does to complete the sale. When items are expensive or important, after-care takes on greater significance because the person really wants to be right. Also, the more alternatives from which to choose, the greater the doubt after a decision is made and the more important the after-care. Department stores pioneered money-back guarantees so customers could return items if cognitive dissonance occurred.

Realistic sales presentations and ad campaigns reduce post-sale dissatisfaction because consumer expectations do not then exceed reality. If overly high expectations are created, a consumer is more apt to be unhappy because performance is not at the level promised. Combining an honest sales presentation with good customer after-care reduces or eliminates cognitive dissonance and dissatisfaction.

4. Types of Consumer Decision Making

Every time a person buys a good or service or visits a retailer, she or he uses a form of the decision process. The process is often undertaken subconsciously, and a person is not aware of its use. Also, as was shown in Figure 7-6, the process is affected by consumer characteristics. Older people may not spend as much time as younger ones in making some decisions due to experience. Well-educated consumers may consult many information sources—increasingly, the Web—before making a decision. Upper-income consumers may spend less time deciding because they can afford to buy again if they are dissatisfied. In a family with children, each member may have input into a decision, which lengthens the process. Class-conscious shoppers may be interested in social sources, including social media. Consumers with low self-esteem or high perceived risk may use all the steps in detail. People under time pressure may skip steps to save time.

The use of the decision process differs by situation. The purchase of a new home usually means a thorough use of each step in the process; perceived risk is high regardless of the consumer’s background. In the purchase of a fast-food meal, the consumer often skips certain steps; perceived risk is low regardless of the person’s background. There are three types of decision processes: extended decision making, limited decision making, and routine decision making.

Extended decision making occurs when a consumer makes full use of the decision process. Much time is spent gathering information and ranking alternatives—what to buy and where to buy—before a purchase. The potential for cognitive dissonance is great. In this category are expensive, complex items with which a person has had little or no experience. Perceived risk of all kinds is high. Items requiring extended decision making include a house, a first car, and life insurance. At any point in the process, a consumer can stop, and for expensive, complex items, this occurs often. Consumer traits (such as age, education, an income) have the most impact.

Because their customers tend to use extended decision making, such retailers as real-estate brokers and auto dealers emphasize personal selling, printed materials, and other communication to provide as much information as possible. A low-key informative approach may be best, so shoppers do not feel threatened. Various financing options may be offered. In this way, the consumer’s perceived risk is minimized.

With limited decision making, a consumer uses all the steps in the purchase process but does not spend a great deal of time on each of them. It requires less time than extended decision making because a person typically has some experience with both the brand and retailer choice of the purchase. This category includes items that have been bought before but not regularly. Risk is moderate, and the consumer spends some time shopping. Priority may be placed on evaluating known alternatives according to a person’s desires and standards, although information search is vital for some. Items requiring limited decision making include a second car, clothing, a vacation, and gifts. Consumer attributes affect decision making, but the impact lessens as perceived risk falls and experience rises. Income, purchase importance, and motives play strong roles.

This form of decision making is relevant to such retailers as department stores, specialty stores, and nonstore retailers that want to sway behavior and that carry goods and services that people have bought before. The shopping environment and assortment are very important. Sales personnel should be available for questions and to differentiate among brands or models.

Routine decision making takes place when the consumer buys out of habit and skips steps in the purchase process. He or she wants to spend little or no time shopping, and the same brands are usually repurchased (often from the same retailers). This category includes items bought regularly. They have little risk due to consumer experience. The key step is problem awareness. When the consumer realizes a good or service is needed, a repurchase is often automatic. Information search, evaluation of alternatives, and post-purchase behavior are unlikely. These steps are not undertaken so long as a person is satisfied. Items involved with routine decision making include groceries, newspapers, and haircuts. Consumer attributes have little impact. Problem awareness almost inevitably leads to a purchase.

This type of decision making is most relevant to such retailers as supermarkets, dry cleaners, and fast-food outlets. For them, the following strategic elements are crucial: a good location, long hours, clear product displays, and, most important, product availability. Ads should be reminder- oriented. The major task is completing the transaction quickly and precisely.

5. Impulse Purchases and Customer Loyalty

Impulse purchases and customer loyalty merit special attention. Impulse purchases arise when consumers buy products and/or brands they had not planned on buying before entering a store, reading a mail-order catalog, seeing a TV shopping show, turning to the Web, and so forth. At least part of consumer decision making is influenced by the retailer. There are three kinds of impulse shopping:

- Completely unplanned. Before coming into contact with a retailer, a consumer has no intention of making a purchase in a goods or service category.

- Partially unplanned. Before coming into contact with a retailer, a consumer has decided to make a purchase in a goods or service category but has not chosen a brand or model.

- Unplanned substitution. A consumer intends to buy a specific brand of a good or service but changes his or her mind about the brand after coming into contact with a retailer.

With the partially unplanned and substitution kinds of impulse purchases, some decisions take place before a person interacts with a retailer. In these cases, a shopper may be involved with extended, limited, or routine decision making. Completely unplanned shopping often relates to routine or limited decision making; there is little or no time spent shopping; the key step is problem awareness.

Traditional store-based strategies to sell impulse goods were to place magazines, gift cards, batteries, and candies near cash registers. This strategy is not as successful as in the past as more consumers are making purchases online or ordering goods for home delivery through grocery lists that do not include these items.22

In studying impulse buying, these are some of the consumer attitudes and behavior patterns that retailers should take into consideration:

- In-store browsing is positively affected by the amount of time a person has to shop.

- Some individuals are more predisposed toward making impulse purchases than others.

- The leading reason given by consumers for impulse shopping is to take advantage of a low price/bargain. Impulse purchases should no longer be viewed of as frivolous behavior— increasingly, it is savvy opportunism. See Figure 7-8.

- Impulse shopping is affected by how stores are arranged. Old Navy reconfigured many of its stores so shoppers could move through the stores more easily and be exposed to more products.

- Impulse shopping is influenced by whether consumers believe that discounts are real.

- Impulse purchasing is not confined to stores. Web-based impulse purchases can be increased through various strategies. These include having an attractive and informative Web site, making it easy to buy items (such as Amazon’s one-click purchasing), offering free shipping, and targeting shoppers based on past purchases, where they live, and media consumption.23

When customer loyalty exists, a person regularly patronizes a particular retailer (store or nonstore) that he or she knows, likes, and trusts. This lets consumers reduce decision making because they do not have to invest time learning about and choosing the retailer from which to purchase. Loyal customers tend to be time-conscious (e.g., shop locally); do not often engage in outshopping; and spend more per shopping trip. In a service setting, such as an auto repair shop, customer satisfaction often leads to shopper loyalty; price has less bearing on decisions. Applying the retailing concept enhances the chances of gaining and keeping customers. This means being customer-oriented, coordinated, value-driven, and goal-oriented. Relationship retailing also helps!

The degree of customer loyalty to retailers can be classified according to five groupings: false loyalty, inertial loyalty, latent loyalty, premium loyalty, and reciprocal loyalty. In false loyalty, customers buy from a retailer only when it is offering special sales or promotions. With inertia loyalty, customers are loyal to a retailer mainly by the convenience of its location for store-based retailers or the ease of ordering and delivery for Web-based retailers. Latent loyal customers are loyal to a retailer, but they are light shoppers. With premium loyalty, people are heavy shoppers and advocates for the retailer among friends and family. The most loyal shoppers are reciprocal loyal. They have a strong relationship with a retailer by being advocates, through high purchase activity and by membership and participation in reward programs.24

Unfortunately, a number of retailers use a one-size-fits-all loyalty program, typically monetary rewards to stimulate repeat visits. Price reductions often do not alter long-run purchase behavior for people who desire more personal service or convenience. After buying from a retailer because of a limited-time price reduction, some shoppers are apt to return to their usual retailers. A better strategy to sustain customer loyalty is to offer tailored rewards, based on what particular shoppers desire. Tailored promotions include merchandise and service upgrades, free shipping by online stores, and messages through cell phone apps, as well as being more effective in enhancing customer engagement and loyalty.25

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Excellent website. A lot of useful information here. I’m sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thanks for your sweat!