The investment project has passed the first three checkpoints in Figure 13: management has decided that investment is the most appropriate entry strategy to build or strengthen a long-term market position and that the actual and prospective investment climates of the target country are acceptable. Now management can move on to checkpoint 4 in Figure 13: Does our economic analysis indicate that the investment project will meet ROI and other objectives, after taking account of risks?

1. Checklist for Assessing Profitability

To assess the project’s profitability, managers need to identify and measure all the many factors that will collectively determine the project’s size and its operating revenues and costs. The accompanying checklist summarizes– these factors.

The sales potential of the project’s product line is the logical place to start the profitability analysis for an investment intended to exploit a target market in the host country. Since the evaluation of foreign market opportunity was the subject of Chapter 2, there is no need to discuss it here. Investigation of the marketing/distribution infrastructure—the availability, quality, and cost of channel intermediaries, advertising agencies, promotional media, and the like—is also necessary to determine the scope and cost of the marketing effort.

Checklist for Evaluating the Profitability of an Investment Entry Project in a Foreign Target Country

- Market factors

- Size and prospective growth (sales potential) of target market for project’s product line.

- Competitive situation.

- Marketing/distribution infrastructure.

- Required scope/cost of marketing effort.

- Export sales potential of project’s product line.

- Displacement of investor’s (parent company’s) exports to target market.

- Projected new export sales to target market of investor’s finished products.

- Production/Supply Factors

- Required capital investment in production facilities.

- Availability/cost of plant site.

- Availability/cost of local raw materials, energy, and other nonlabor inputs.

- Availability/cost of imported inputs from parent company.

- Availability/cost of imported inputs from other sources.

- Transportation, port, and warehousing facilities.

- Labor Factors

- Availability/cost of local managerial, technical, and office staff.

- Availability/cost of expatriate staff.

- Availability/cost of skilled, semiskilled, and unskilled workers.

- Fringe benefits.

- Worker productivity.

- Training facilities and programs.

- Labor relations.

- Capital-Sourcing Factors

- Availability/cost of local long-term investment capital.

- Availability/cost of local working capital.

- Availability/value of host government financial incentives.

- Required investment by parent company.

- Tax Factors

- Kinds of taxes and tax rates.

- Allowable depreciation.

- Tax incentives/exemptions.

- Tax administration.

- Tax treaty with investor’s country.

Although the project is intended to serve the market in the target country, its revenues may not be limited to local sales. Additional revenues may come from export sales to third countries by the project (affiliate) and from new export sales of finished products to the target country by the investing (parent) company through the project’s more effective marketing organization. Conversely, the parent company may lose revenues if the project displaces existing exports of products that will now be manufactured in the target country. All these factors should be considered to arrive at a projection of the project’s revenues and its marketing costs over the planning period. These same factors also influence the project’s size.

The size of the project together with the capital intensity of the production process determines the required investment in land, plant, and equipment. The project’s running production costs will depend on the availability and cost of all inputs needed to achieve the planned level or levels of production. Calculating the cost of imported inputs requires a determination of transportation costs and import duties. If the project uses certain inputs (for example, components) from the parent company, then the latter will earn a net profit contribution, which should be taken into account when estimating the net cash flow from the project to the parent company. In some instances, import restrictions may compel the use of locally sourced inputs, whose availability or quality may be less satisfactory than that of inputs from abroad.

In many foreign projects, the principal operating costs are labor inputs. In general, the use of expatriate personnel should be kept low because of its high cost and host government policies that favor local nationals. But in most instances, the parent company will need to send its own people to the target country to get the project off the ground. Estimates of unit labor costs require information on wage rates, productivity, and fringe benefits. Training facilities and programs may be necessary to upgrade labor skills, particularly in developing countries. Managers should also assess prospective relations with the project’s local workers—the ideology and strength of unions, the right to hire and fire, the role of labor in management, and so on. The availability of labor may constrain the project’s size, and labor costs may also influence capital requirements through their effect on the optimum mix of capital and labor inputs. In developing countries it may be profitable to substitute local labor for capital.

Capital-sourcing factors in the target country will bear strongly on the financial structure of the project, namely, the parent company’s capital contribution relative to the contribution of local sources.10 The availability of long-term loan or equity capital from local sources can reduce the size ft’ the parent company’s own investment outlay. Host government financial incentives (such as construction grants, low-interest loans, and plant leasing) can have the same effect.11 Local equity contributions usually occur in the form of a joint venture. In the case of sole ventures, parent companies generally finance plant and equipment expenditures with their own funds, but rely on local sources to cover working capital requirements.

Since managers need to assess the project’s profitability on an after-tax basis, they must calculate the effect of all local taxes (including depreciation rules) on the project’s cash flow and, where applicable, of local taxes on the transfer of income from the project to the parent company. They must also calculate the effect of home country (II.S.) taxes on income repatriated from the project to estimate the project’s after-tax dollar return. Because of the complexities of host and home country tax systems and the relations between them (which may or may not be formalized in a treaty), the determination of an after-tax project return can benefit from the expertise of an international tax analyst. In some countries, taxes are negotiated with authorities who are not always competent or honest.

As is true of the investment climate checklist presented earlier in this chapter, the project profitability checklist is only suggestive. Company management should develop its own checklist to make certain it covers all the factors critical to the project’s profitability.

2. Discounted Cash Flow Analysis

The results of the investigation outlined in the previous section need to be brought together in a financial analysis of the project. The recommended form of capital budgeting is a discounted cash flow analysis that takes into account the time value of money. It is not our purpose to trace the financial analysis of a foreign investment project, but rather to identify the special features that distinguish capital budgeting for a foreign project from that for a domestic project.12

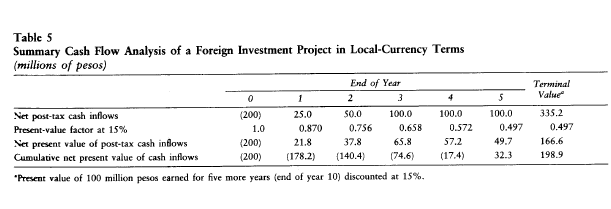

Table 5 presents the summary cash flow analysis of a foreign investment project in local-currency terms, that is to say, from the perspective of the project rather than from the perspective of the parent company. The investor’s time horizon is ten years, but estimated cash flows are shown for only five years, with a terminal value indicating the project’s market value at the end of the fifth year.

The estimated net post-tax cash inflows are the financial expression of the project’s ten-year operations plan, involving estimates of both operating revenues and costs. The negative cash inflow in year 0 represents the initial investment outlay in the host country currency (pesos). The investor’s required rate of return (hurdle rate) on domestic investments is 15 percent, and this same rate is used to discount the foreign project’s net cash inflows over the planning period. The cumulative net present value of net cash inflows becomes positive in year 5, indicating that the project’s return exceeds the 15 percent hurdle rate.13 Including terminal value, the internal rate of return is close to 38 percent.14

Managers are advised to make a local-currency cash flow analysis from the standpoint of the foreign project so that they can judge the sensitivity of local-currency cash flows to expropriation and operations risks.15 But the critical measure of profitability is the project’s rate of return to the investor or parent company, as determined by repatriable cash flows expressed in the investor’s home currency (dollars.).

The cash flow analysis from the standpoint of the investing company focuses only on that company’s original cash outlay (equity and loan capital contributions to the project) and the cash flows which it receives, or which are freely available, from the project in dollars. It includes, therefore, the parent company’s initial investment in the project and all net cash inflows from the project (dividends, interest, royalties, management/ technical fees, profits on export sales net of any profits lost through export displacement, and so on) that are available to the parent company in dollars, whether or not they are actually transferred to the home country. It is evident that this dollar cash flow analysis can be completed only by assessing all limitations on the repatriation of funds from the target country and by assuming exchange rates to convert from the local currency to dollars. By its very nature, therefore, dollar cash flow analysis must adjust for transfer risks (Figure 14). It must also adjust for any withholding taxes imposed by the host government on the repatriation of funds and for U.S. taxes on repatriated funds.16 After these adjustments are made, the net present value of the dollar cash flows should be calculated by using the parent company’s domestic hurdle rate as the discount factor. If the net present value is zero or positive over the planning period, then the foreign investment project passes this last financial test.

3. Adjusting Cash Flows for Political Risk

Managers can use two different approaches to adjust project cash flows for political risk. One approach is to lump together all the project’s political risks by adding a risk premium to the investor’s domestic hurdle rate and then calculating the net present value of the foreign project at the higher rate.17 Thus the investor would discount cash flows at, say, 25 percent rather than, say, 15 percent. The second approach is to adjust the project’s estimated cash flows period by period for specific political risks.

The only advantage of the risk-premium approach is its ease of application, a feature that explains its popularity. But it suffers from several drawbacks. First, the risk premium can be determined by managers arbitrarily without any systematic appraisal of political risks. Its use, therefore, encourages a casual treatment of risk. Second, this approach assumes that political risk will be uniform over the entire planning period, an assumption that is patently in error. Expropriation risk, for example, is lower in the early years of an investment than in the later years, and inconvertibility risk usually responds to shifts in the balance of payments. By ignoring the time pattern of uncertainties, the risk-premium approach tends to reduce early cash flows too much and later cash flows too little. After all, the investor ordinarily has less uncertainty about political changes in the host country over the next few years than at a more distant time. Third, this approach assumes that it is possible to capture the effects of different political risks in a single discount rate. However, as our discussion of political risks indicates, different classes of political events do not pose the same risks for a project’s viability and profitability.

Year-by-year adjustment of cash flows for political risk has none of the drawbacks of the risk-premium approach. The application of this approach requires managers to assess the sensitivity of the project’s cash flows to possible political events or situations in the host country. One way to do this is to estimate the probability of a specific political event (say, expropriation) for each year of the investment planning period, and then to weight the annual cash flows by these probabilities to get their expected values or “certainty equivalents.” Many techniques are available to improve probability judgments—for example, decision trees, Bayesian statistics, and computer simulation. Another way is to assess the sensitivity of the project’s cash flows to different political scenarios of the host country by asking “what if” questions. When used systematically, the scenario technique will provide a range for the project’s cash flows. It may be used by managers who are uneasy working with probabilities, or it may be combined with probability analysis. Whatever techniques they use, managers should assess the sensitivity of the project’s cash flows to specific political risk with the same care they use to assess market risks.

The argument for directly adjusting cash flows is strongest for operations and transfer risks and weakest for general political risk, with expropriation risk somewhere in the middle. It makes little sense to adjust cash flows for general instability risk, because that risk is a threat to the entire investment project. Rather, general instability risk should be considered in a go, no-go decision framework. Many companies would also treat expropriation risk in the same way, but there is good reason to assess the sensitivity of cash flows to this class of risk. Managers may conclude, for example, that expropriation is not a threat until after the discounted payback period of the investment project. A simple go, no-go decision on the expropriation risk may, therefore, prevent a company from making a desirable investment.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

I have been examinating out many of your posts and it’s pretty good stuff. I will definitely bookmark your blog.