To appreciate the role of retailing and the range of retailing activities, let’s view it from three perspectives:

- Suppose we manage a manufacturing firm that makes cosmetics. How should we sell these items? We could distribute via big chains such as Sephora or small neighborhood stores, have our own sales force visit people in their homes as Mary Kay does, or set up our own stores (if we have the ability and resources to do so). We could sponsor TV infomercials or magazine ads, complete with a toll-free phone number.

- Suppose we have an idea for a new way to teach first-graders how to use computer software for spelling and vocabulary. How should we implement this idea? We could lease a store in a strip shopping center and run ads in a local paper, rent space in a local YMCA and rely on teacher referrals, or do mailings to parents and visit children in their homes. In each case, the service is offered “live.” But there is another option: We could use an animated Web site to teach children online.

- Suppose that we, as consumers, want to buy apparel. What choices do we have? We could go to a department store or an apparel store. We could shop with a full-service retailer or a discount store. We could go to a shopping center or order from a catalog. We could patronize retailers that carry a wide range of clothing (from outerwear to jeans to suits) or firms that specialize in one clothing category (such as leather coats). We could surf the Web and visit retailers around the globe. We could also look at Facebook and see what other consumers are saying about various retailers.

There is a tendency to think of retailing as primarily involving the sale of tangible (physical) goods. However, retailing also includes the sale of services and digital goods. And this is a big part of retailing! A service may be the shopper’s primary purchase (such as a haircut) or it may be part of the shopper’s purchase of a good (such as furniture delivery). Sales in many physical goods—product categories such as books, movies, and music—are now dominated by their digital applications in the format of downloads. Obviously, retailing does not have to involve a store. Mail and phone orders, direct selling to consumers in their homes and offices, Web transactions, kiosks, and vending machine sales all fall within the scope of retailing. In fact, retailing does not even have to include a “retailer.” Manufacturers, importers, nonprofit firms, wholesalers, and individual artisans on online platforms, such as Etsy.com, act as retailers when they sell to final consumers.

Let’s now examine various reasons for studying retailing and its special characteristics.

Reasons for Studying Retailing

Retailing is an important field to study because of its impact on the economy, its functions in distribution, and its relationship with firms selling goods and services to retailers for their resale or use. These factors are discussed next. A fourth factor for students of retailing is the broad range of career opportunities, as highlighted with a “Careers in Retailing” box in each chapter, Appendix A at the end of this book, and our blog (www.bermanevansretail.com). See Figure 1-2.

1. THE IMPACT OF RETAILING ON THE ECONOMY

Retailing is a major part of U.S. and world commerce. Retail sales and employment are vital economic contributors, and retail trends often mirror trends in a nation’s overall economy.

According to the Department of Commerce, annual U.S. retail store sales in 2015 were $4.785 trillion—representing one-third of the total economy. During that year, more than one-fifth of the world’s retail sales occurred in the United States.2 The weighted-average share of retail E-commerce in overall U.S. retail sales has been steadily growing from 3.4 percent in 2007 to 7.1 percent in 2015.3 Share of online retail sales is slightly higher in Europe at 7.5 percent and highest in the Asia-Pacific region at 10.2 percent. Telephone and mail-order sales by nonstore retailers, vending machines, and direct selling generate hundreds of billions of dollars in additional yearly revenues. Personal expenditures on financial, medical, legal, educational, and other services account for another several hundred billion dollars in annual retail revenues.

Durable goods stores—including motor vehicles and parts dealers; furniture, home furnishings, electronics and appliance stores; and building materials and hardware stores—make up 30 percent of U.S. retail store sales. Nondurable goods and services stores—including general merchandise stores; food and beverage stores; health- and personal-care stores; gasoline stations; clothing and accessories stores; sporting goods, hobby, book, and music stores; eating and drinking places; and miscellaneous retailers—together account for 70 percent of U.S. retail store sales.

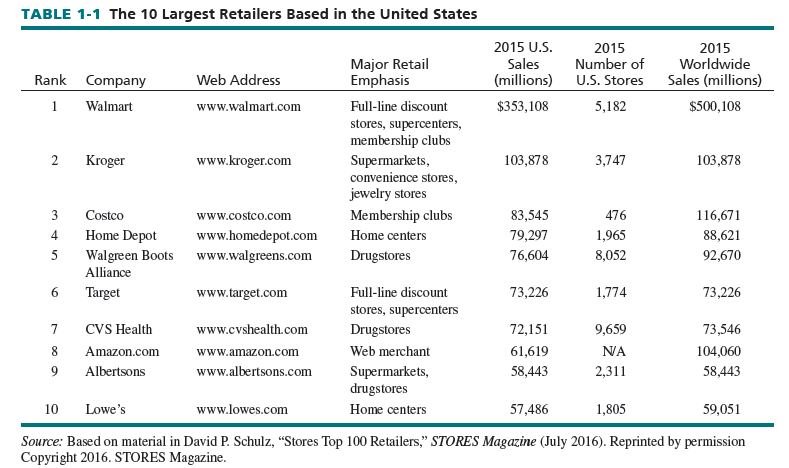

The world’s 250 largest retailers generate more than $4.6 trillion in annual revenues. They represent 29 nations. Seventy-six of the largest 250 retailers are based in the United States, 28 in Japan, 17 in Germany, 16 in Great Britain, and 15 in France. Five of the 250 top retailers are nonstore retailers.4 The 10 largest retailers in the United States generate nearly one trillion dollars in annual domestic revenues and more than 1.2 trillion dollars in total worldwide sales. They operate over 32,000 U.S. stores. See Table 1-1. Visit our blog (www.bermanevansretail.com) for additional information on retailing.

Retailing is a major source of jobs. In the United States alone, 15 million people—about one- tenth of the total labor force—work for traditional retailers (including food and beverage service firms, such as restaurants). Yet this figure understates the true number of people who work in retailing because it does not include the several million persons employed by other service firms, seasonal employees, proprietors, and unreported workers in family businesses or partnerships.

Retailing is the largest private-sector employer in the United States. According to the National Retail Federation, anyone whose employment results in a consumer product—from those who supply raw materials to manufacturers to truck drivers who deliver goods—counts on retail for their livelihood. With 35 million stores and the vast number of suppliers, the retail industry is responsible for 42 million jobs, and $1.6 trillion in labor income, and it accounts for $2.6 trillion of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

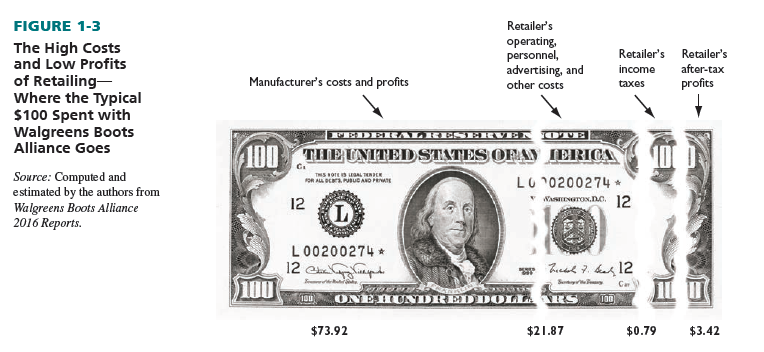

From a cost perspective, retailing is a significant field of study. In the United States in 2015, on average, 36 cents of every dollar spent in department stores, 47 cents spent in women’s apparel stores, and 28 cents spent in pharmacies and drugstores go to the retailers to cover operating costs, activities performed, and profits. Costs include rent, displays, wages, ads, and maintenance. Only a small part of each dollar is profit. Profit margins in the retail sector vary. Whereas audio/video and consumer electronics stores have pre-tax profit margins of 4.2 percent, the pre-tax profit margins averaged 2.1 percent for department stores in 2015.6 In its fiscal year ending January 31, 2016, Walmart, the world’s largest retailer, had after-tax profits of 3.1 percent of sales.7 Figure 1-3 shows costs and profits for Walgreens Boots Alliance, an international drugstore chain.

2. RETAIL FUNCTIONS IN DISTRIBUTION

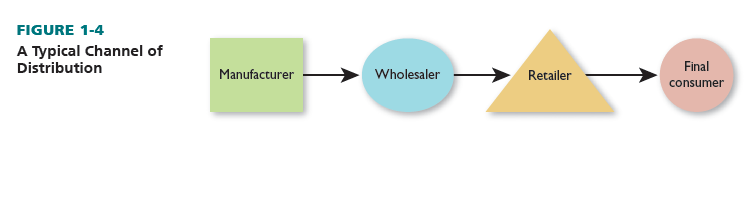

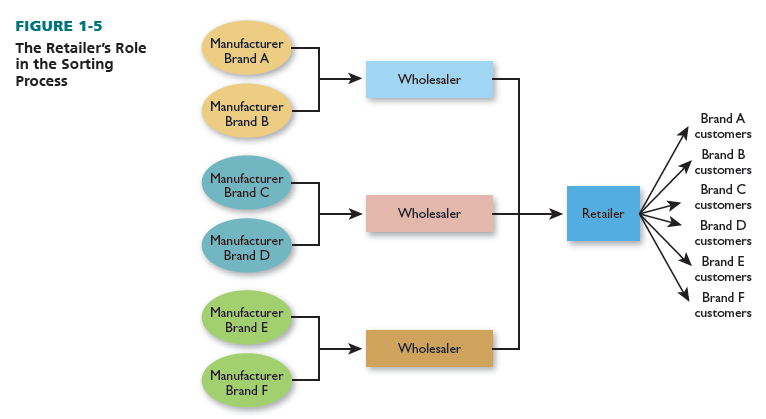

Retailing is the last stage in a channel of distribution—all the businesses and people involved in the physical movement and transfer of ownership of goods and services from producer to consumer. A typical distribution channel is shown in Figure 1-4. Retailers often act as the contact between manufacturers, wholesalers, and the consumer. Many manufacturers would like to make one basic type of item and sell their entire inventory to as few buyers as possible, but consumers usually want to choose from a variety of goods and services and purchase a limited quantity. Retailers collect an assortment from various sources, buy in large quantity, and sell in small amounts. This is the sorting process. See Figure 1-5.

Another job for retailers is communicating both with customers and with manufacturers and wholesalers. Shoppers learn about the availability and characteristics of goods and services, store hours, sales, and so on from retailer ads, salespeople, and displays. Manufacturers and wholesalers are informed by their retailers with regard to sales forecasts, delivery delays, customer complaints, defective items, inventory turnover, and more. Many goods and services have been modified due to retailer feedback.

For small suppliers, retailers can provide assistance by transporting, storing, marking, advertising, and pre-paying for products. Small retailers may need the same type of help from their suppliers. The tasks performed by retailers affect the percentage of each sales dollar they need to cover costs and profits.

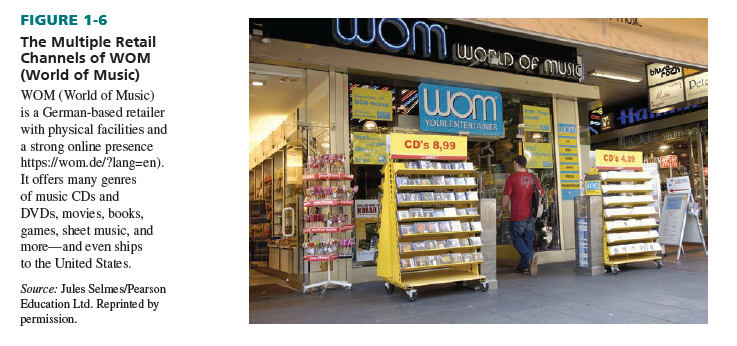

Retailers also complete transactions with customers. This means having convenient locations, filling orders promptly and accurately, and processing credit purchases. Some retailers also provide customer services such as gift wrapping, delivery, and installation. To make themselves even more appealing, many firms now engage in omnichannel retailing, whereby a retailer sells to consumers through multiple retail formats (points of contact). Most large retailers operate both physical stores and Web sites to make shopping easier and to accommodate consumer desires. Some firms provide information and sell to customers through multiple touch points: retail stores, mail order, Web sites, tablets, smartphones, and a toll-free phone number. See Figure 1-6.

For these reasons, products are usually sold through retailers not owned by manufacturers (wholesalers). This lets the manufacturers reach more customers, reduce costs, improve cash flow, increase sales more rapidly, and focus on their area of expertise. Select manufacturers, such as Sherwin-Williams, Coach, and Nike, operate retail facilities (besides selling at independent retailers). In running their stores, these firms complete the full range of retailing functions and compete with conventional retailers.

3. THE RELATIONSHIPS AMONG RETAILERS AND THEIR SUPPLIERS

Relationships among retailers and suppliers can be complex. Because retailers are part of a distribution channel, manufacturers and wholesalers must be concerned about the caliber of displays, customer service, store hours, and retailers’ reliability as business partners. Retailers are also major customers of goods and services for resale, store fixtures, computers, management consulting, and insurance.

These are some issues over which retailers and their suppliers have different priorities: control over the distribution channel, profit allocation, the number of competing retailers handling suppliers’ products, product displays, promotion support, payment terms, and operating flexibility. Due to the growth of large chains, retailers have more power than ever. Unless suppliers know retailer needs, they cannot have good rapport with them; so long as retailers have a choice of suppliers, they will choose those offering more.

Channel relations tend to be smoothest with exclusive distribution, whereby suppliers make agreements with one or a few retailers that designate the latter as the only ones in specified geographic areas to carry certain brands or products. This stimulates both parties to work together to maintain an image, assign shelf space, allot profits and costs, and advertise. It also usually requires that retailers limit their brand selection in the specified product lines; they might have to decline to handle other suppliers’ brands. From the manufacturers’ perspective, exclusive distribution may limit their long-run total sales.

Channel relations tend to be most volatile with intensive distribution, whereby suppliers sell through as many retailers as possible. This often maximizes suppliers’ sales and lets retailers offer many brands and product versions. Competition among retailers selling the same items is high; retailers may use tactics not beneficial to individual suppliers, because they are more concerned about their own results. Retailers may assign little space to specific brands, set very high prices on them, and not advertise them.

With selective distribution, suppliers sell through a moderate number of retailers. This combines aspects of exclusive and intensive distribution. Suppliers have higher sales than in exclusive distribution, and retailers carry some competing brands. It encourages suppliers to provide some marketing support and retailers to give adequate shelf space. See Figure 1-7.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

This website is mostly a walk-by for all of the information you wished about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely uncover it.

You have brought up a very superb details, thankyou for the post.