There seems to be general agreement that training and development is a good thing, and that it increases productivity, but the question is ‘how much?’ It is even difficult to show a causal link between HR development and organisational performance, partly because such terms are difficult to define precisely, and partly because the payoff from development may not be seen in the short term. It is also difficult to tie down performance improvements to the development itself and to understand the nature of the link. For example, is performance better because of increased or different HR development, because the reward package has improved or because we have a clearer set of organisational and individual objectives? If there is a link with HR development initiatives, is it that employees have better skills, or that they are better motivated, or that they have been selected from a more able group of candidates attracted to the organisation as it offers a high level of development?

In spite of these difficulties it is important to identify the contribution of HR development to business success, and wider measures for assessing business success, beyond the standard financial indicators, make this more feasible, as, for example, suggested by Kaplan and Norton (1992) and discussed in Chapter 33. While the search for ‘evidence’ goes on, the current climate encourages high levels of attention to HR development, which is increasingly seen not only as a route to achieving business strategy, but also as a means of building core competence over the longer term to promote organisational growth and sustained competitive advantage. Global competition and a fast pace of change have emphasised the importance of the human capital in the organisation, and the speed and ways in which they learn. A Green Paper produced by the Department for Education and Employment (1998) stated that ‘investment in human capital will be the foundation of success in the 21st century’. Nationally the emphasis on qualifications is increasing and Case 16.1 on this book’s companion website, www.pearsoned.co.uk/ torrington, focuses on the development of directors from this perspective.

In addition, levels and sophistication of training and development have received considerable attention in the context of the ‘new psychological contract’ and the need to promote employability, which we discuss in more detail in Chapter 19. There is some evidence that employee demand for training and development is increasing and that unions are beginning to engage in bargaining for development. Opportunities for training and development may be a vital tool in recruitment and retention, and considered to be a reward when promotion or monetary rewards are less available. However, Stewart and Tansley (2002) found significant structural and cultural barriers to formal and informal learning in organisations; in particular lack of time was identified as an issue.

1. THE NATIONAL PICTURE AND STRATEGY

Employee development has traditionally been seen as a cost rather than an investment in the UK, although this is certainly changing in some organisations. It has been argued that UK organisations give little support to training and development compared with our European partners (see, for example, Handy 1988; Constable and McCormick 1987 for keystone reports). This lack of investment in training and development has been identified as a major factor in Britain’s economic performance, and it has been argued that without such investment we will be trapped in a low-wage, low-skills economy (Rainbird 1994; Keep and Mayhew 1999), with the emphasis on competing on price rather than quality. In recent years in the UK there has been a governmental focus on

measures to increase our skills levels and reduce skills gaps, which we review in more detail in the following chapter. Despite these efforts, and some evidence from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey (WERS) that training for core employees has increased between 1998 and 2004 (Kersley et al. 2006), evidence of skills gaps remains (see, for example, Phillips 2006). Our national training framework is voluntarist, with the government’s role limited to encouraging training rather than intervening, as in many other countries. High levels of skills are seen as critical in promoting high performance and wealth as a country.

Alternatively it has been argued that it is not a lack of investment in training that is the problem but the way such investment is distributed, that is, who it is spent on and the content of the training. It is generally agreed that training spend is unevenly distributed. For example Stevens (2001) argues that it is the people at the lower end of the hierarchy that miss out on training, and Westwood (2001) reports that:

Access to workforce development is unequal with managers and professionals or those with a degree up to five times more likely to receive work based training than people with no qualification and/or unskilled jobs. (p. 19)

Thomson (2001) explains that broader development is concentrated on those at the beginning of their careers and those in more senior and specialist posts, rather than part- timers and those with fewer qualifications to begin with. The WERS survey found that professionals, associated professionals, managers and those with most qualifications receive most training rather than low-skilled workers (Kersley et al. 2006). In the aerospace and pharmaceuticals businesses, defined as high-skills sectors, Lloyd (2002) found a conflict of interests between employees’ desire for training and development and managerial short-term aims, lack of accreditation of skills, structured development focused on key employees, access to training being dependent on individual initiative, senior managers viewing training as a minor issue to be dealt with by lower-level managers and insufficient resources. She suggests that there was under-investment and lack of support for flexibility and employability. Westwood (2001) concludes that while we do not do as much training as in Europe, we do spend a lot of money on training that doesn’t last very long and on the people who may not need it. In terms of training content there is evidence to suggest that much training is related to induction and particularly health and safety, as demonstrated in the WERS survey, and it has been argued that this does nothing to drive the development of a knowledge-based economy (see, for example, Westwood 2001). In addition there is considerable ongoing evidence that employees in small organisations are at a disadvantage in terms of access to training. In the construction industry overall low levels of apprenticeships and a heavy reliance on contingent (temporary) workers were found, particularly in smaller organisations (Forde and MacKenzie 2004), and evidence from the WERS survey suggests that the highest levels of training are in the public sector and larger organisations, particularly those employing high levels of professional employees.

Some view the solution to this problem as increasing state intervention, as many view voluntarism as having a limited effect (see, for example, Sloman 2001). It is argued that potential intervention would not mean a return to the levy system, where employers were forced to make an annual payment relative to profits which they could recoup by providing evidence that the equivalent money had been spent of training. But, for example, statutory rights for paid study leave and employer tax credits, and funding mechanisms to create a demand-led system, could be introduced.

A demand-led approach is currently receiving much attention, but there are subtle differences in how this is interpreted. The Leitch Review (Leitch 2006) provides a useful starting point in differentiating between a supply-led and a demand-led training system. He characterises the supply-driven approach as being based on ineffectively articulated collective employer views of training needed and a central system of provision planned by the government to meet these needs, and predict future needs. He suggests that employers and individuals find it difficult to articulate their needs partly due to the profusion of bodies to which they are asked to input, that this approach results in too little investment by employers, too little responsibility being taken by individuals for their own training and a qualifications system divorced from the needs of the workplace. In contrast he suggests a demand-led system is about directly responding to demand rather than planning supply. To achieve this suppliers (such as colleges of further education) only receive funding as they attract customers (rather than being given block funding in advance, based on estimated demand), driving them to respond flexibly and immediately to employer demand. He suggests this approach, as used in Employer Training Pilots (which we discuss in the following chapter), leads to training provision which is more relevant, reflects the needs of customer, and is likely to produce higher completion rates and better value for money.

Keep (2006) identifies current problems for demand-led and employer-led training in terms of the mismatch between employer needs and training provision. For example he suggests that colleges offer longer-term accredited courses as these attach Learning and Skills Council funding in response to government targets, whilst employers may be seeking short uncertificated courses. Such a mismatch is addressed in the recommendations of the Leitch Review, and we highlight the principles and mechanisms proposed to achieve Leitch’s 2020 vision for the UK being a world leader in skills in the following chapter. If these mechanisms are effective, training supply should be much more reactive to the real needs of employers; however the limitations of this approach are that such a reactive approach focuses on current and short-term needs at the expense of anticipating and preparing for future needs, and does not address the structure of jobs in this country.

There is, however, a subtly different school of thought in relation to the supply/ demand debate which suggests the problem lies with the demand side of the equation rather than the supply side. In other words the problem is not with government initiatives and measures to encourage training, development and learning but with the way that skills are used and jobs are constructed, and hence the employer demand for training, development and learning. In speaking of the Learning and Skills Councils (LSCs), Stevens (2002) says that he is less concerned with what the LSCs can do to encourage learning than with ‘whether the UK can generate enough jobs for people who have learnt and can learn’ (p. 44). Lloyd (2002) suggests that the country cannot solve its problems just by developing skills, as it is critical to change the structure of jobs:

All this suggests that we still have a situation in which the majority of organizations are using a reactive strategy: training only in response to the immediate short-term demands of the business, rather than being considered a strategic issue. (Ashton 2003, p. 23)

This implies that training and development needs to be considered at a strategic level in the business, but also, and perhaps more challenging, that employers need to change their business strategies to focus on quality rather than cost. Lloyd (2005), however, in the context of research in the fitness industry suggests that even this may not be enough to shift the low-skills equilibrium, and that amongst other things, customer expectations in this country need to be higher.

2. ORGANISATIONAL STRATEGY AND HR DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY

For training and development to be effective in terms of business success there is a well- rehearsed argument that it should be linked upfront with business strategy, and the WERS survey (Kersley et al. 2006) did find evidence that there was more training in organisations with a strategic plan that covered employee development. McClelland’s research (1994) is one of many studies showing that organisations generally do not consider development issues to be part of their competitive strategy formulation, but those that do so identified it to be of value in gaining as well as maintaining competitive advantage. Miller (1991), writing specifically of management development, points to a lack of fit between business strategy and development activity. Miller makes the point that although at the organisational level it is difficult to identify quantitatively the direct impact of strategic investment in development, this impact is well supported by anecdotal evidence and easily demonstrated at the macro-level.

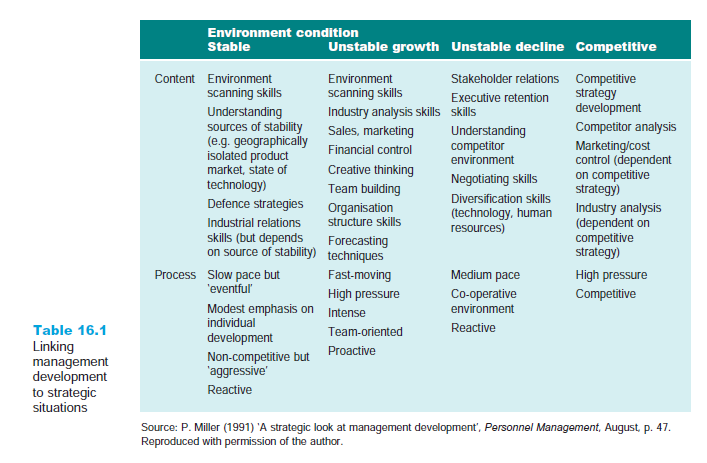

Those organisations that do consider HR development at a strategic level usually see it as a key to implementing business strategy in a reactive way. Luoma (2000) categorises this approach as a ‘needs-driven’ approach, where the purpose of the HR development strategy is to identify and remedy skill deficiencies in relation to the organisational strategy. Luoma suggests that in many articles this is ‘implicitly referred to as the only way of managing strategic HRD’. Miller, for example, has demonstrated how management development can be aligned with the strategic positioning of the firm, and this can be seen as coming within the broad remit of such approaches as a needs-driven approach. He has produced a matrix demonstrating how development content and processes can reflect stable growth, unstable growth, unstable decline and competitive positions, as shown in Table 16.1. He offers the model as suggestive, only, of the ‘possibilities in designing strategically-oriented management development programmes’.

Luoma (2000), however, identifies a second approach to HR development strategy which is an ‘opportunistic approach’, where the impetus is external rather than internal. This would include applying leading ideas on development to the organisation in a more general way, rather than specifically in relation to meeting the current business objectives. Such ideas may be developed from benchmarking, case studies, networking and the academic and practitioner press. Such ideas could include content and method, for example the development of a corporate university, and the concept of developing nonemployees who perhaps work for suppliers or who are contracted to the organisation. The abilities thus developed may indeed be relevant in achieving business objectives, but they may also be relevant in developing abilities and behaviours which may be the source of future competitiveness. Thus they may also be a means of achieving culture change and/or facilitating the strategy process itself by constructing it as a learning process. In this approach the learning potential of all employees will be emphasised, and the HR development strategy may meet reactive needs in the implementation of business strategy, but may also be proactive in influencing the formation of future business strategy.

The third approach to the strategy link suggested by Luoma is based on the concept, which we discussed in Chapter 2, of organisational capability as the key to sustained competitive advantage, the resource-based view of the firm. This approach is proactive in that it focuses on the desired state of the organisation as defined in its future vision. Within this would come the interest in anticipatory learning, which has been attracting some interest, where future needs are predicated and development takes place in advance.

Of paramount importance, therefore, is the ability to learn. Watkins (1987) suggests that development for strategic capability, rather than just targeting development on achieving business objectives, needs to reinforce an entrepreneurial and innovative culture in which learning is part of everyday work. He identifies the importance of acting successfully in novel and unpredictable circumstances and that employees acquire a ‘habit of learning, the skills and learning and the desire to learn’. Within this same perspective Mayo (2000) suggests that the intangible assets of the organisation are increasing in proportion to the value of tangible assets. He recognises that developing intellectual capital may be an ‘act of faith’, or one of budgetary allocation, and suggests that the most useful measures to track such investments are individual capability, individual motivation, the organisational climate and work-group effectiveness. While he recognises the value of competency frameworks in respect of individual development he does point out that these neglect such features as experience and the networks and range of personal contacts, both of which are key to the development of core organisational competencies which are in turn key to developing uniqueness.

In a slightly different but compatible approach McCracken and Wallace (2000) develop a redefinition of strategic HR development, based on an initial conception by Garavan (1991). They suggest nine characteristics of a strategic approach to HR development, which are that:

- HR development shapes the organisation’s mission and goals, as well as having a role in strategy implementation.

- Top management are leaders rather than just supporters of HR development.

- Senior management, and not just HR development professionals, are involved in environmental scanning in relation to HR development.

- HR development strategies, policies and plans are developed, which relate to both the present and future direction of the organisation, and the top management team are involved in this.

- Line managers are not only committed and involved in HR development, but involved as strategic partners.

- There is strategic integration with other aspects of HRM.

- Trainers not only have an expanded role, including facilitation and acting as organisational change consultants, but also lead as well as facilitate change.

- HRD professionals have a role in influencing the organisational culture.

- There is an emphasis on future-oriented cost effectiveness and results, in terms of evaluation of HR development activity.

They suggest that each of these aspects needs to be interrelated in an open system. In the following sections we will address some of these characteristics in more detail; however it is worth bearing in mind that changing learning patterns and HR development roles both place challenges on the alignment of learning and development with business needs (for more details see Hirsh and Tamkin 2005).

3. THE EXTERNAL LABOUR MARKET AND HR STRATEGIC INTEGRATION

The external availability of individuals with the skills and competencies required by the organisation will also have an impact on employee development strategy. If skilled individuals are plentiful, management has the choice of whether, and to what extent, it wishes to develop staff internally. If skilled individuals are in short supply, internal development invariably becomes a priority. Predicting demographic and social changes is critical in identifying the extent of internal development required and also who will be available to be developed. In-depth analysis may challenge traditionally held assumptions about who will be developed, how and to what extent. For example, the predicted shortage of younger age groups in the labour market, coupled with a shortage of specific skills, may result in a strategy to develop older rather than younger recruits. This poses potential problems about the need to develop older workers some of whom may learn more slowly. What is the best form of development programme for employees with a very varied base of skills and experiences? Another critical issue is that of redeployment of potentially redundant staff and their development to provide skills that are in short supply.

Prediction of skills availability is critical, as for some jobs the training required will take years rather than months. Realising in January that the skills required in August will not be available in the labour market is too late if the development needed takes three years!

The external labour market clearly has a big impact on employee development strategy, so it is important that there is effective integration between HR development strategy, other aspects of human resource strategy and overall organisational strategy. Currently many skills gaps are being covered by the recruitment of immigrant workers with valued skills and who employers often consider to work very willingly and very hard. However Philpott and Davies (2006) warn that if employers see the immigrant labour force as a quick fix for skills shortages this may undermine employers’ efforts to develop the existing workforce.

Where there is a choice between recruiting required skills or developing them internally, given a strategic approach, the decision will reflect on the positioning of the organisation and its strategy. In Chapter 5 we looked at this balance in some depth and you may find it helpful to re-read this. A further issue is that of ensuring a consistency between the skills criteria used for recruitment and development.

From a slightly different perspective, the impact of the organisation’s development strategy on recruitment and retention, either explicit or implicit, is often underestimated. There is increasing evidence to show that employees and potential employees are more interested in development opportunities, especially structured ones, than in improvements in financial rewards. Development activity can drive motivation and commitment, and can be used in a strategic way to contribute towards these. For these ends, publishing and marketing the strategy is key, as well as ensuring that the rhetoric is backed up by action. There is also the tricky question of access to and eligibility for development. If it is offered only very selectively, it can have the reverse of the intended impact.

However, not all employees see the need for, nor the value of, development and this means that reward systems need to support the development strategy, a topic to which we return in Chapter 26. If we want employees to learn new skills and become multiskilled, it is skills development we need to reward rather than the job that is currently done. If we wish employees to gain vocational qualifications, we need to reflect this in our recruitment criteria and reward systems. Harrison (1993) notes that these links are not very strong in most organisations.

Other forms of reward, such as promotions and career moves, also need to reflect the development strategy; for example, in providing appropriate, matrix, career pathways if the strategy is to encourage a multifunctional, creative perspective in the development of future general management. Not only do the pathways have to be available, they also have to be used, and this means encouraging current managers to use them for their staff. In Chapter 19 we explore such career issues more fully.

Finally, an organisation needs to reinforce the skills and competencies it wishes to develop by appraising those skills and competencies rather than something else. Developmentally based appraisal systems can clearly be of particular value here. Mabey and Iles (1993) note that a strategic approach to development differs from a tactical one in that a consistent approach to assessment and development is identified with a common skills language and skills criteria attached to overall business objectives. They also note the importance of a decreasing emphasis on subjective assessment. To this end many organisations have introduced a series of development centres, similar to the assessment centres discussed in Chapter 8, but with a clear outcome of individual development plans for each participant related to their current levels of competence and potential career moves, and key competencies required by the business.

4. TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT ROLES

Salaman and Mabey (1995) identify a range of stakeholders in strategic training and development, each of which will have different interests in, influence over and ownership of training and development activities and outcomes. They identify senior managers as the sponsors of training and development, who will be influenced by professional, personal and political agendas; and business planners as the clients who are concerned about customers, competitors and shareholders. Third, they identify line managers who are responsible for performance, coaching and resources; and fourth, participants who are influenced by their career aspirations and other non-work parts of their lives. HRM staff are identified as facilitators who are concerned with best practice, budget credibility and other HR strategy. Lastly, training specialists are identified as providers, who are influenced by external networks, professional expertise and educational perspectives. The agendas of each of these groups will overlap on some issues and conflict on others. We have already noted how McCracken and Wallace (2000) have redefined the roles of top managers, line managers and HR professionals so that they are all more proactively involved in HRD strategy. Sloman (2006) defines the role of trainer in a service-led, knowledge-driven economy as ‘that of a people developer, and [it] is about supporting, accelerating and directing learning that meets the organisation’s needs and that are appropriate to the learner and the context’ (p. 35).

Most organisational examples suggest that the formation of training and development strategy is not something that should be ‘owned’ by the HR/HRD function. The strategy needs to be owned and worked on by the whole organisation, with the HR/ HRD function acting in the roles of specialist/expert and coordinator. The function may also play a key role in translating that strategy into action steps. The actions themselves may be carried out by line management, the HR/HRD function or outside consultants. Stewart and Tansley (2002) suggest that the immediate and medium-term contribution of HRD professionals should focus on developing the competence and motivation of managers to manage learning and development. They confirm that such professionals need to act as facilitators and not instructors, and have a focus on the process and design of development rather than its content. There is a debate about where the training and development function should be located in order best to fulfil its role; and the balance between central specialists concentrating on strategic activities and local specialists integrated into departments needs to be appropriate to the organisational context. Hirsh and Tamkin (2005) provide an informed discussion of the central/local tension.

Involvement of line management in the delivery of the training and development strategy can have a range of advantages. Top management have a key role in introducing and promoting strategic developments to staff, for example creating an organisationwide competency identification programme; setting up a system of development centres or introducing a development-based organisational performance management system. Only if management carry out this role can employees see and believe that there is a commitment from the top. At other levels line managers can be trained as trainers, assessors and advisers in delivering the strategy. This is a mechanism not only for getting them involved, but also for tailoring the strategy to meet the real and different needs of different functions and departments.

External consultants may be used at any stage. They may add to the strategy development process, but there is always the worry that their contribution comes down to an offering of their ready-packaged solution, with a bit of tailoring here and there, rather than something which really meets the needs of the organisation. It is useful to have an outside perspective, but there is an art in defining the role of that outside contribution.

In delivery, external consultants may make a valuable contribution where a large number of courses have to be run over a short period. The disadvantages are that they can never really understand all the organisational issues, and that they may be seen as someone from outside imposing a new process on the organisation.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I gotta favorite this website it seems very helpful handy