1. Calculating Future Values

Money can be invested to earn interest. So, if you are offered the choice between $100 today and $100 next year, you naturally take the money now to get a year’s interest. Financial managers make the same point when they say that money has a time value or when they quote the most basic principle of finance: A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

Suppose you invest $100 in a bank account that pays interest of r = 7% a year. In the first year, you will earn interest of .07 X $100 = $7 and the value of your investment will grow to $107:

Value of investment after 1 year = $100 X (1 + r) = 100 X 1.07 = $107

By investing, you give up the opportunity to spend $100 today, but you gain the chance to spend $107 next year.

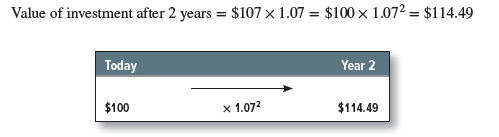

If you leave your money in the bank for a second year, you earn interest of .07 X $107 = $7.49 and your investment will grow to $114.49:

Notice that in the second year you earn interest on both your initial investment ($100) and the previous year’s interest ($7). Thus your wealth grows at a compound rate and the interest that you earn is called compound interest.

If you invest your $100 for t years, your investment will continue to grow at a 7% compound rate to $100 X (1.07/. For any interest rate r, the future value of your $100 investment will be

Future value of $100 = $100 X (1 + r)t

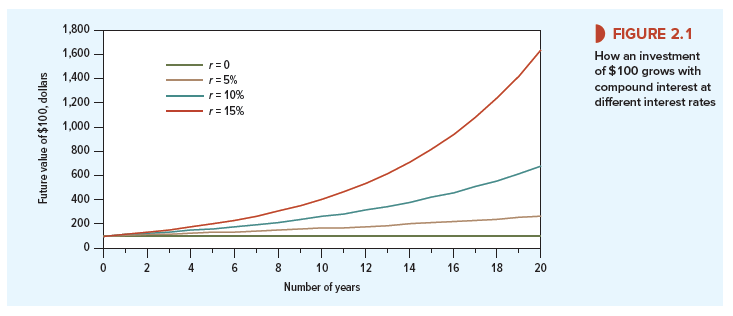

The higher the interest rate, the faster your savings will grow. Figure 2.1 shows that a few percentage points added to the interest rate can do wonders for your future wealth. For example, by the end of 20 years, $100 invested at 10% will grow to $100 X (1.10)20 = $672.75. If it is invested at 5%, it will grow to only $100 X (1.05)20 = $265.33.

2. Calculating Present Values

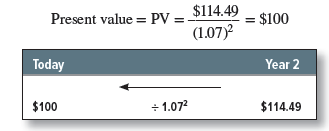

We have seen that $100 invested for two years at 7% will grow to a future value of 100 X 1.072 = $114.49. Let’s turn this around and ask how much you need to invest today to produce $114.49 at the end of the second year. In other words, what is the present value (PV) of the $114.49 payoff?

You already know that the answer is $100. But, if you didn’t know or you forgot, you can just run the future value calculation in reverse and divide the future payoff by (1.07)2:

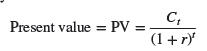

In general, suppose that you will receive a cash flow of Ct dollars at the end of year t. The present value of this future payment is

The rate, r, in the formula is called the discount rate, and the present value is the discounted value of the cash flow, Ct. You sometimes see this present value formula written differently. Instead of dividing the future payment by (1 + r)t, you can equally well multiply the payment by 1/(1 + r)t. The expression 1/(1 + r)t is called the discount factor. It measures the present value of one dollar received in year t. For example, with an interest rate of 7% the two-year discount factor is

DF2 = 1/(1.07)2 = .8734

Investors are willing to pay $.8734 today for delivery of $1 at the end of two years. If each dollar received in year 2 is worth $.8734 today, then the present value of your payment of $114.49 in year 2 must be

Present value = DF2 x C2 = .8734 x 114.49 = $100

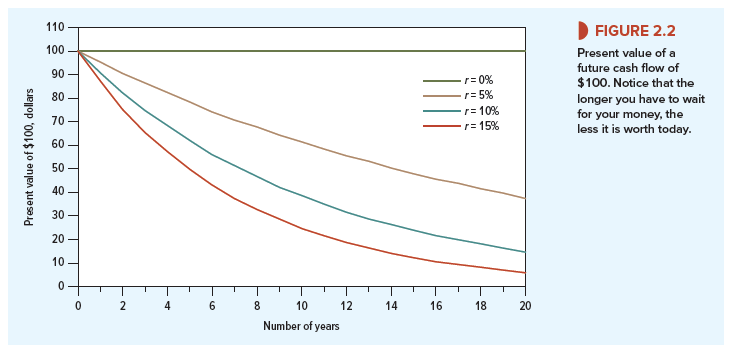

The longer you have to wait for your money, the lower its present value. This is illustrated in Figure 2.2. Notice how small variations in the interest rate can have a powerful effect on the present value of distant cash flows. At an interest rate of 5%, a payment of $100 in year 20 is worth $37.69 today. If the interest rate increases to 10%, the value of the future payment falls by about 60% to $14.86.

3. Valuing an Investment Opportunity

How do you decide whether an investment opportunity is worth undertaking? Suppose you own a small company that is contemplating construction of a suburban office block. The cost of buying the land and constructing the building is $700,000. Your company has cash in the bank to finance construction. Your real estate adviser forecasts a shortage of office space and predicts that you will be able to sell next year for $800,000. For simplicity, we will assume initially that this $800,000 is a sure thing.

The rate of return on this one-period project is easy to calculate. Divide the expected profit ($800,000 – 700,000 = $100,000) by the required investment ($700,000). The result is 100,000/700,000 = .143, or 14.3%.

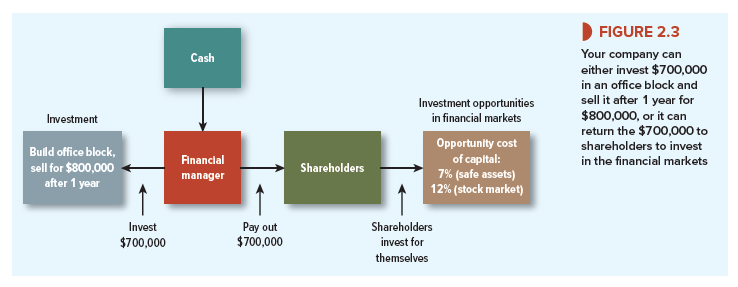

Figure 2.3 summarizes your choices. (Note the resemblance to Figure 1.2 in the previous chapter.) You can invest in the project or pay cash out to shareholders, who can invest on their own. We assume that they can earn a 7% profit by investing for one year in safe assets (U.S. Treasury debt securities, for example). Or they can invest in the stock market, which is risky but offers an average return of 12%.

What is the opportunity cost of capital, 7% or 12%? The answer is 7%: That’s the rate of return that your company’s shareholders could get by investing on their own at the same level of risk as the proposed project. Here the level of risk is zero. (Remember, we are assuming for now that the future value of the office block is known with certainty.) Your shareholders would vote unanimously for the investment project because the project offers a safe return of 14% versus a safe return of only 7% in financial markets.

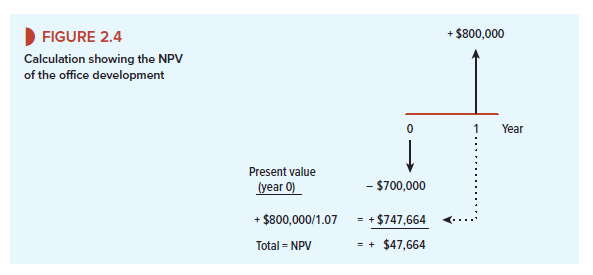

The office-block project is therefore a “go,” but how much is it worth and how much will the investment add to your wealth? The project produces a cash flow at the end of one year. To find its present value we discount that cash flow by the opportunity cost of capital:

![]()

Suppose that as soon as you have bought the land and paid for the construction, you decide to sell your project. How much could you sell it for? That is an easy question. If the venture will return a surefire $800,000, then your property ought to be worth its PV of $747,664 today.

That is what investors in the financial markets would need to pay to get the same future payoff. If you tried to sell it for more than $747,664, there would be no takers because the property would then offer an expected rate of return lower than the 7% available on government securities. Of course, you could always sell your property for less, but why sell for less than the market will bear? The $747,664 present value is the only feasible price that satisfies both buyer and seller. Therefore, the present value of the property is also its market price.

4. Net Present Value

The office building is worth $747,664 today, but that does not mean you are $747,664 better off. You invested $700,000, so the net present value (NPV) is $47,664. Net present value equals present value minus the required investment:

NPV = PV – investment = 747,664 – 700,000 = $47,664

In other words, your office development is worth more than it costs. It makes a net contribution to value and increases your wealth. The formula for calculating the NPV of your project can be written as:

![]()

Remember that C0, the cash flow at time 0 (that is, today) is usually a negative number. In other words, C0 is an investment and therefore a cash outflow. In our example, C0 = -$700,000.

When cash flows occur at different points in time, it is often helpful to draw a timeline showing the date and value of each cash flow. Figure 2.4 shows a timeline for your office development. It sets out the net present value calculation assuming that the discount rate r is 7%.1

5. Risk and Present Value

We made one unrealistic assumption in our discussion of the office development: Your real estate adviser cannot be certain about the profitability of an office building. Those future cash flows represent the best forecast, but they are not a sure thing.

If the cash flows are uncertain, your calculation of NPV is wrong. Investors could achieve those cash flows with certainty by buying $747,664 worth of U.S. government securities, so they would not buy your building for that amount. You would have to cut your asking price to attract investors’ interest.

Here we can invoke a second basic financial principle: A safe dollar is worth more than a risky dollar. Most investors dislike risky ventures and won’t invest in them unless they see the prospect of a higher return. However, the concepts of present value and the opportunity cost of capital still make sense for risky investments. It is still proper to discount the payoff by the rate of return offered by a risk-equivalent investment in financial markets. But we have to think of expected payoffs and the expected rates of return on other investments.[1]

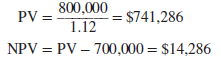

Not all investments are equally risky. The office development is more risky than a government security but less risky than a start-up biotech venture. Suppose you believe the project is as risky as investment in the stock market and that stocks are expected to provide a 12% return. Then 12% is the opportunity cost of capital for your project. That is what you are giving up by investing in the office building and not investing in equally risky securities.

Now recompute NPV with r = .12:

The office building still makes a net contribution to value, but the increase in your wealth is smaller than in our first calculation, which assumed that the cash flows from the project were risk-free.

The value of the office building depends, therefore, on the timing of the cash flows and their risk. The $800,000 payoff would be worth just that if you could get it today. If the office building is as risk-free as government securities, the delay in the cash flow reduces value by $52,336 to $747,664. If the building is as risky as investment in the stock market, then the risk further reduces value by $33,378 to $714,286.

Unfortunately, adjusting asset values for both time and risk is often more complicated than our example suggests. Therefore, we take the two effects separately. For the most part, we dodge the problem of risk in Chapters 2 through 6, either by treating all cash flows as if they were known with certainty or by talking about expected cash flows and expected rates of return without worrying how risk is defined or measured. Then in Chapter 7 we turn to the problem of understanding how financial markets cope with risk.

6. Present Values and Rates of Return

We have decided that constructing the office building is a smart thing to do since it is worth more than it costs. To discover how much it is worth, we asked how much you would need to invest directly in securities to achieve the same payoff. That is why we discounted the project’s future payoff by the rate of return offered by these equivalent-risk securities—the overall stock market in our example.

We can state our decision rule in another way: Your real estate venture is worth undertaking because its rate of return exceeds the opportunity cost of capital. The rate of return is simply the profit as a proportion of the initial outlay:

![]()

The cost of capital is once again the return foregone by not investing in financial markets. If the office building is as risky as investing in the stock market, the return foregone is 12%.

Since the 14.3% return on the office building exceeds the 12% opportunity cost, you should go ahead with the project.

Building the office block is a smart thing to do, even if the payoff is just as risky as the stock market. We can justify the investment by either one of the following two rules:3

- Net present value rule. Accept investments that have positive net present values.

- Rate of return rule. Accept investments that offer rates of return in excess of their opportunity costs of capital.

Properly applied, both rules give the same answer, although we will encounter some cases in Chapter 5 where the rate of return rule is easily misused. In those cases, it is safest to use the net present value rule.

7. Calculating Present Values When There Are Multiple Cash Flows

One of the nice things about present values is that they are all expressed in current dollars—so you can add them up. In other words, the present value of cash flow (A + B) is equal to the present value of cash flow A plus the present value of cash flow B.

![]()

Suppose that you wish to value a stream of cash flows extending over a number of years. Our rule for adding present values tells us that the total present value is:

![]()

This is called the discounted cash flow (or DCF) formula. A shorthand way to write it is

where £ refers to the sum of the series of discounted cash flows. To find the net present value (NPV) we add the (usually negative) initial cash flow:

![]()

Example 2.1 • Present Values with Multiple Cash Flows

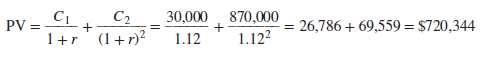

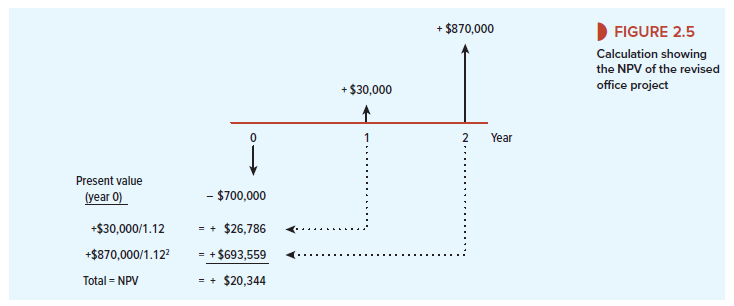

Your real estate adviser has come back with some revised forecasts. He suggests that you rent out the building for two years at $30,000 a year, and predicts that at the end of that time you will be able to sell the building for $840,000. Thus there are now two future cash flows—a cash flow of C1 = $30,000 at the end of one year and a further cash flow of C2 = (30,000 + 840,000) = $870,000 at the end of the second year.

The present value of your property development is equal to the present value of C1 plus the present value of C2. Figure 2.5 shows that the value of the first year’s cash flow is Ci/(1 + r) = 30,000/1.12 = $26,786 and the value of the second year’s flow is C2/(1 + r)2 = 870,000/1.122 = $693,559. Therefore our rule for adding present values tells us that the total present value of your investment is:

It looks as if you should take your adviser’s suggestion. NPV is higher than if you sell in year 1: NPV = $720,344 – $700,000 = $20,344

Your two-period calculations in Example 2.1 required just a few keystrokes on a calculator. Real problems can be much more complicated, so financial managers usually turn to financial calculators especially programmed for present value calculations or to computer spreadsheet programs. A box near the end of the chapter introduces you to some useful Excel functions that can be used to solve discounting problems.

8. The Opportunity Cost of Capital

By investing in the office building you are giving up the opportunity to earn an expected return of 12% in the stock market. The opportunity cost of capital is therefore 12%. When you discount the expected cash flows by the opportunity cost of capital, you are asking how much investors in the financial markets are prepared to pay for a security that produces a similar stream of future cash flows. Your calculations showed that these investors would need to pay $720,344 for an investment that produces cash flows of $30,000 at year 1 and $870,000 at year 2. Therefore, they won’t pay any more than that for your office building.

Confusion sometimes sneaks into discussions of the cost of capital. Suppose a banker approaches. “Your company is a fine and safe business with few debts,” she says. “My bank will lend you the $700,000 that you need for the office block at 8%.” Does this mean that the cost of capital is 8%? If so, the project would be even more worthwhile. At an 8% cost of capital, PV would be 30,000/1.08 + 870,000/1.082 = $773,663 and NPV = $773,663 – $700,000 = +$73,663.

But that can’t be right. First, the interest rate on the loan has nothing to do with the risk of the project: it reflects the good health of your existing business. Second, whether you take the loan or not, you still face the choice between the office building and an equally risky investment in the stock market. A financial manager who borrows $700,000 at 8% and invests in an office building is not smart, but stupid, if the company or its shareholders can borrow at 8% and make an equally risky investment in the stock market offering an even higher return. That is why the 12% expected return on the stock market is the opportunity cost of capital for your project.

Wonderful work! This is the kind of info that should be shared around the web.

Disgrace on the search engines for no longer positioning this

put up upper! Come on over and talk over with my web site .

Thank you =)

I think other website owners should take this website as an example , very clean and great user friendly style and design.