A foreign investment project must be analyzed in the context of its political, legal, economic, social, and cultural environments—the investment climate of the target country. Although sensitivity to particular environmental factors varies from one project to another, all projects are subject to the influence of some set of environmental factors. Managers, therefore, should raise three questions about a country’s investment climate: (1) Which variables in the investment climate are critical to the success of the project? (2) What is the present behavior (value) of these critical variables? (3) How are these critical variables likely to change over the investment planning period?

In making domestic investment decisions, U.S. managers seldom pay much attention to the investment climate, implicitly assuming that it will remain constant or change only slowly over the investment’s life. But it is dangerous to extend this approach to foreign investment decisions, because in many foreign countries the investment climate is far more dynamic than at home. Furthermore, American managers are far less knowledgeable about foreign investment climates than about the U.S. climate, in which they have functioned as persons all of their lives.

The accompanying checklist presents the many features of a target country’s investment climate that need to be assessed by managers. The checklist is only suggestive, for each investor should develop his own check-list to make certain it covers all the critical variables of the project’s contextual environment. Of special note is the fact that all the items in the checklist depend directly or indirectly on the behavior of the political system in the host country. For that reason, changes in the investment climate will proceed mainly from changes in the behavior of the host government or from general political instability. Because the future is uncertain, management’s assessment of prospective political behavior in the host country can be expressed at most in probability terms. Hence the assessment of a country’s future investment climate is an assessment of the project’s political risk.

Checklist for Evaluating the Investment Climate of a Foreign Target Country

- General Political Stability

- Past political behavior.

- Form of government.

- Strength/ideology of government.

- Strengths/ideologies of rival political groups.

- Political, social, ethnic, and other conflicts.

- Government Policies Toward Foreign Investment

- Past experience of foreign investors.

- Attitude toward foreign investment.

- Foreign investment treaties and agreements.

- Restrictions on foreign ownership.

- Local content requirements.

- Restrictions on foreign staff.

- Other restrictions on foreign investment.

- Incentives for foreign investment.

- Investment entry regulations.

- Other Government Policies and Legal Factors

- Enforceability of contracts.

- Fairness of courts.

- Corporate/business law.

- Labor laws.

- Taxation.

- Import duties and restrictions.

- Patent/trademark protection.

- Antitrust/restrictive practices laws.

- Honesty/efficiency of public officials.

- Macroeconomic Environment

- Role of government in the economy.

- Government development plans/programs.

- Size/growth rate of gross national product.

- Size/growth rate of population.

- Size/growth rate of per-capita income.

- Distribution of personal income.

- Sectorial distribution of industry, agriculture, and services.

- Transportation/communications system.

- Rate of inflation.

- Government fiscal/monetary policies.

- Price controls.

- Availability/cost of local capital.

- Management-labor relations.

- Membership in customs unions or free trade areas.

- International Payments

- Balance of payments.

- Foreign exchange position/external indebtedness.

- Repatriation restrictions.

- Exchange rate behavior.

1. What Is Political Risk?

For the international manager, political risk arises from his uncertainty over the continuation of present political conditions and government policies in the foreign host country that are critical to the profitability of an actual or proposed equity/contractual business arrangement. In most instances, political risk proceeds from uncertainty that the host government or a successor government will arbitrarily change the “rules of the game” so as to cause a loss or freezing of earnings and assets, including the entire foreign venture in the event of expropriation.7

Political risks are conventionally distinguished from market risks, which derive from uncertainty about future changes in cost, demand, and competition in the marketplace. All other uncertainties (apart from insurable casualty risks) are regarded as political. But this distinction breaks down in practice. So pervasive is the role of government today that conventional market risks are often more the consequence of political than economic forces. Given this interdependence between political and market phenomena, managers are called upon to evaluate all project risks without arbitrary distinctions between political and market risks.

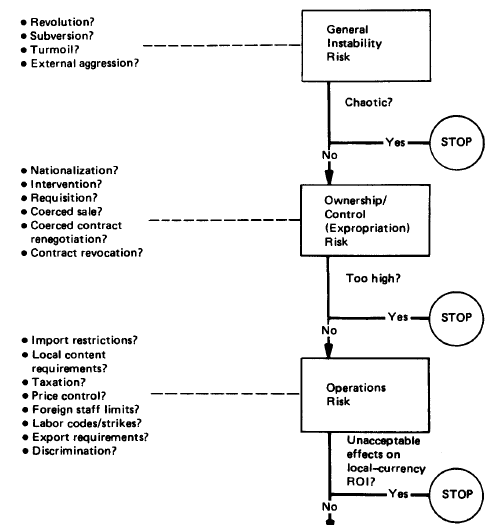

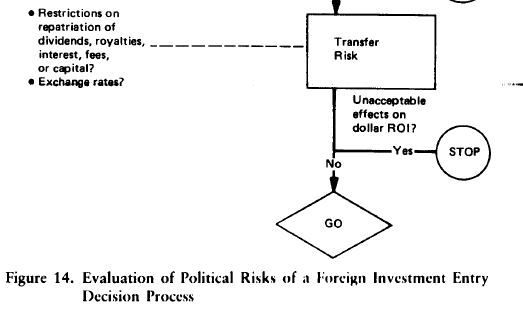

Having made this point, we nonetheless need to define political risk if we are to talk about it. A pragmatic definition is as follows: Political risk is created by a foreign investor’s uncertainty about (1) general instability in the host country’s political system in the future and/or (2) future acts by the host government that would cause loss to the investor. In terms of their potential impact on an investment entry project, political risks may be grouped into four classes: general instability risk, ownership/control risk, operations risk, and transfer risk.

General instability risk proceeds from management’s uncertainty about the future viability of the host country’s political system. The Iranian revolution illustrates this class of risk. When it occurs, general political instability may not always force the abandonment of an investment project, but it will almost certainly interrupt operations and lower profitability.

Ownership!control risk proceeds from management’s uncertainty about host government actions that would destroy or limit the investor’s ownership or effective control of his affiliate in the host country. This class of risk includes several kinds of expropriatory acts by (or sanctioned by) the host government that deprive the investor of his property.

Operations risk proceeds from management’s uncertainty about host government policies or acts sanctioned by the host government that would constrain the investor’s operations in the host country, whether in production, marketing, finance, or other business functions.

Transfer risk derives mainly from management’s uncertainty about future government acts that would restrict the investor’s ability to transfer payments or capital out of the host country—that is, the risk of inconvertibility of the host country’s currency. A second type of transfer risk is depreciation of the host currency relative to the home currency of the investor. Exchange depreciation (or, more generally, exchange rate behavior) is almost always the result of government action or the consequence of government policies.

2. Evaluating Political Risks

Evaluation of the political risks of a proposed foreign investment requires managers to get answers to questions such as the following:

- How likely is general political instability in the host country over our investment planning period (say, five years)?

- Barring a general political collapse, how long is the present government likely to remain in power?

- How strong is the present government’s commitment to the current rules of the game (for example, ownership rights) in light of its attitude toward foreign investors (ideology) and its power position?

- If the present government is succeeded, what changes in the current rules of the game would the new government be likely to make?

- How would likely changes in the rules of the game affect the safety and profitability of our investment project?

Getting answers to these questions is seldom easy, particularly for a developing country. But it is possible to collect relevant information from both secondary and primary sources and to evaluate that information in a systematic way.8 To help managers structure the collection and analysis of information on political risks, Figure 14 offers a four-hurdle model. This model is an elaboration of step 3 in Figure 13.

The first hurdle is an assessment of general instability risk in the target country. If managers anticipate a chaotic political situation over the planning period, they will stop any further investigation of the investment entry proposal. Otherwise, they will go on to an assessment of ownership/control risks—the probability of expropriatory actions taken by the host government toward the investor’s project. Expropriation is the compulsory or coercive deprivation of foreign-owned property by action taken, or sanctioned by, a host government. Nationalization is the taking of foreign- owned property with transfer of title to the host government.’ Intervention is the seizure of foreign-owned property either by the government or by a private group (such as workers) supported by the government. Requisition is similar to intervention, but it is undertaken by a government (often, the military) in response to an emergency situation, with the expectation that the property will be returned to its foreign owners at a later time. Coerced sale is action by the host government to compel foreign investors to sell all or part of their property to a government entity or to local nationals, usually at less than market value. Coerced contract renegotiation is action by a host government to compel a foreign investor to agree to changes in his contract with that government. Finally, contract revocation is the unilateral termination by the host government of its contract with a foreign investor.

In the majority of expropriation cases, foreign investors sooner or later receive some compensation, but it seldom meets the international standard of “prompt, effective, and adequate.” Since expropriation is about the worst action a host government can take against an investor, the expropriation risk of a project should be carefully assessed by managers. Unwarranted fear of expropriation is as much to be avoided by managers as is an unexamined belief that expropriation is something that happens only to other investors.

If the expropriation risk is judged acceptable, managers move to the third hurdle—operations risk. To assess operations risk, managers must first determine the character of the project’s operations (inputs, outputs, size, and so on), as well as its expected cash flows over the planning period, so that they can then evaluate the probable effects of risk factors on local- currency ROI. What is required, therefore, is an integration of the risk and profitability assessments of the project, a subject taken up in the next section.

The final hurdle is transfer risk. Managers in companies that insist on periodic dividends and other payments from a foreign affiliate are particularly concerned with transfer risk. On the other hand, managers in companies that plan to reinvest earnings in the target country for some time into the future will pay far less attention to the transfer risk, recognizing that transfer restrictions come and go with changes in the balance of payments.

Ultimately, of course, all investors want to repatriate earnings and capital. In contrast to repatriation restrictions, the exchange rate risk is seldom critical to the success of a project. But to assess that risk, managers need to forecast the likely direction of changes in the dollar value of the host country’s currency over the planning period and then to estimate the net effects of those changes on the cash flow of the project. Ordinarily, the net effects will be inconsequential, because the exchange rate will reflect the internal rate of inflation, and thus higher prices in the local market will act to offset the lower dollar value of the host country currency.

If the project passes the four political risk hurdles and satisfies the investor’s required rate of return, then it is ready for approval by top management.

3. Political Risk Insurance

In some instances, the final approval of a foreign investment project may hinge on the availability and cost of insurance against political risks. U.S. companies may be able to obtain insurance against the risks of inconvertibility, expropriation, and war, revolution, and insurrection in some 85 developing countries from the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), a U.S. government agency in Washington. Political risk insurance may also be purchased from private insurers, notably the American International Group (AIG) and Lloyd’s of London.

The general availability of political risk insurance, however, does not relieve managers from the responsibility of making their own assessment of a project’s political risks. For one thing, OPIC insurance is available for only certain developing countries and then only for a new investment that is judged beneficial to the host country and not detrimental to U.S. employment or the balance of payments. Second, political risk insurance can be costly, ranging from annual OPIC rates of 1.5 percent for combined coverage up to 10 percent for private insurance. Third, insurance covers only book-value loss, which is often considerably less than market-value loss. For these reasons, investors will have to shoulder at least some exposure to political risk. In any event, they will need their own risk assessment of a project to make an informed decision on whether or not and how much to insure.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021