With direct channels, the firm sells directly to foreign distributors, retailers, or trading companies. Direct sales can also be made through agents located in a foreign country. Direct exporting can also be expensive and time consuming. However, it offers manufacturers opportunities to learn about their markets and customers in order to forge better relationships with their trading partners. It also allows firms greater control over various activities. Heli Modified Inc. of Maine, USA, which manufactures custom-made handles for motorcycles, attributes much of its export success to U.S. government agencies as well as to its international network of sales agents and distributors. The company now exports to about twenty- five countries on four continents.

The decision whether to market products directly or to use the services of an intermediary is based on several important factors.

1. International Marketing Objectives of the Firm

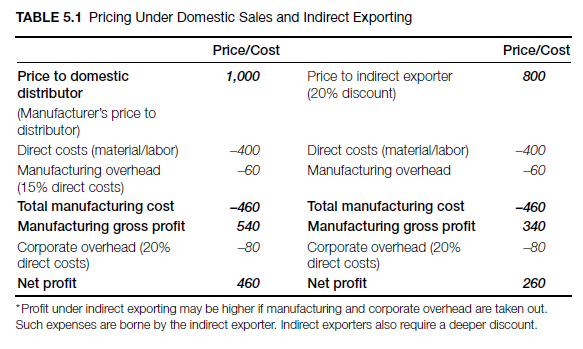

The marketing objectives of the firm with respect to sales, market share, profitability, and level of financial commitment will often determine channel choice. Direct exporting is likely to provide opportunities for high profit margins, even though it requires a high degree of financial commitment (Figure 5.1 and Table 5.1).

2. Manufacturer’s Resources and Experience

A direct-channel structure may be neither feasible nor desirable in light of the firm’s limited resources and/or commitment. Small to medium-size firms appear to use indirect channels due to their limited resources and small export volumes, whereas large firms use similar channels because of trade barriers in the host country that may restrict or prohibit direct forms of ownership (Kogut, 1986). Firms in the early phases of their internationalization efforts tend to use independent intermediaries more than those with greater experience (Anderson and Coughlin, 1987; Kim, Nugent, and Yhee, 1997).

3. Availability and Capability of Intermediary

Every country has certain distribution patterns that have evolved over the years and that are complemented by supportive institutions. Firms that have used specific types of distribution channels in certain countries may find it difficult to use similar channels in other countries. This occurs in cases in which distributors have exclusive arrangements with other suppliers/ competitors or when such channels do not exist.

4. Customer and Product Characteristics

If the number of consumers is large and concentrated in major population centers, the company may opt for direct or multiple channels of distribution. In Japan, for example, more than half of the population lives in the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka market area (Cateora, Gilly, and Graham, 2010). Another factor is that customers may also have developed a habit of buying from a particular channel and may be reluctant to change in the short term.

Direct exporting is often preferable if customers are geographically homogeneous, have similar buying habits, and are limited in number, which allows for direct customer contact and greater control (Seifert and Ford, 1989). The choice of channel structure is primarily dictated by market considerations. However, in certain situations, the nature of the product determines channel choice. In a study on export channels of distribution in the United States, 52.7 percent of the respondents indicated that the distribution was primarily dictated by the market, while 15.5 percent stated that the choice was dictated by the nature of the product exported (Seifert and Ford, 1989). For example, industrial equipment of considerable size and value that requires more after-sales service is usually exported to the user or through the use of other direct channels. Direct channels are also frequently used for products of a perishable nature or high unit value (since it will bring more profit) or for products that are custom made or highly differentiated. Smaller equipment, industrial supplies, and consumer goods, on the other hand, tend to have longer channels. In Canada, for example, consumer goods are purchased by importing wholesalers, department stores, mail-order houses, chain stores, and single-line retailers.

5. Marketing Environment

The use of direct channels is more likely in countries that are similar in culture to the exporter’s home country. For example, U.S. sales to Canada are characterized by short (direct) marketing channels, unlike the indirect channels used in Japan and Southeast Asia. In certain cases, firms have limited options in the selection of appropriate channels for their products. In the lumber industry, the use of export intermediaries is the norm in many countries. In Finland, more than 90 percent of distribution of nondurable consumer goods is handled by four wholesale chains. Exporters have to use these distribution channels to gain a significant penetration of the market (Czinkota, Ronkainen, and Moffett, 2010). Legislation in certain countries requires that foreign firms be represented by local firms that are wholly owned by nationals of the country. Exporters must market their goods indirectly by appointing a local agent or distributor. Some studies support the use of direct/integrated channels when there is a high degree of environmental uncertainty. The establishment of integrated channels is intended to place the firm closer to the market so that it can react and adapt to unforeseen circumstances (Klein, Frazier, and Roth, 1990).

6. Control and Coverage

A direct or integrated channel affords the manufacturer more control over its distribution and its link to the end user. However, it is not a practical option for firms that do not have adequate foreign market knowledge or the necessary financial, operational, and strategic capabilities.

Firms that use indirect channels are still able to exercise control mechanisms to coordinate and influence foreign intermediary actions. Two types of controls are available for the manufacturer/exporter: process controls and output controls. Under process controls, the manufacturer’s intervention is intended to influence the means intermediaries use to achieve desirable ends (e.g., selling technique, servicing procedure, promotion). Output controls are used to influence indirectly the ends achieved by the distributor. The latter includes monitoring sales volume, profits, and other performance-based indicators (Bello and Gilliland, 1997). It is important to note the following salient points with respect to manufacturers’ coordination and control of independent foreign intermediaries:

- Manufacturers must rely on both unilateral and bilateral (collaboration) control mechanisms in order to organize and manage their export relationships with independent foreign intermediaries.

- The use of output controls tends to have a positive impact on foreign intermediaries’ overall performance. Process controls, however, do not appear to account for performance benefits, largely due to manufacturers’ inadequate knowledge of foreign marketing procedures.

- Firms that export highly technical and sophisticated products tend to exercise high levels of control (process and output controls) over foreign intermediaries in order to protect their proprietary rights (trade secrets/know-how), as well as to address unique customer needs.

In terms of coverage, firms that use longer channels tend to use different intermediaries (intensive coverage). However, recent studies show a positive relationship between channel directness and intensive coverage. This means that firms that employ direct methods to reach their overseas customers tend to use a large number of different types of channel intermediaries.

7. Types of Intermediaries

One of the distinguishing features of direct and indirect channel alternatives is the location of the second channel. If the second channel is located in the producer’s country, it is considered an indirect channel, whereas if it is located in the buyer’s country, it is assumed to be a direct channel. This means that agents, distributors, and other middlemen could be in either category, depending on whether they are located in the buyer’s or the seller’s country.

Channel alternatives are also defined on the basis of ownership of the distribution channel. A direct channel is one owned and managed by the company, as opposed to one in which distribution is handled by outside agents and middlemen. A firm’s channel structure is also defined in terms of the percentage of equity held in the distribution organization: majority ownership (greater than 50 percent) is treated as a direct or integrated channel, while less than majority ownership is considered an indirect channel. The first definition of channel alternatives is used in this chapter.

8. Indirect Channels

Several types of intermediaries are associated with indirect channels, and each type offers distinct advantages. Indirect channels are classified here on the basis of their functions.

9. Exporters That Sell on Behalf of the Manufacturer

9.1. Manufacturer’s Export Agents (MEAs)

Manufacturer’s export agents usually represent various manufacturers of related and noncompeting products. They may also operate on an exclusive basis. It is an ideal channel to use especially in cases involving a widespread or thin overseas market. It is also used when the product is new and demand conditions are uncertain. The usual roles of the MEA are as follows:

- Handle direct marketing, promotion, shipping, and sometimes financing of merchandise. The agent does not offer all services.

- Take possession but not title to the goods. The MEA works for commission; risk of loss remains with the manufacturer.

- Represent the manufacturer on a continuous or permanent basis as defined in the contract.

9.2. Export Management Companies (EMCs)

EMCs act as the export department for one or several manufacturers of noncompetitive products. More than 2,000 EMCs in the United States provide manufacturers with extensive services that include but are not limited to market analyses, documentation, financial and legal services, purchase for resale, and agency services (locating and arranging sale). An EMC often does extensive research on foreign markets, conducts its own advertising and promotion, serves as a shipping/forwarding agent, and provides legal advice on intellectual property matters. It also collects and furnishes credit information on overseas customers.

Most EMCs are small and usually specialize by product, foreign market, or both. Some are capable of performing only limited functions such as strategic planning or promotion. Export management companies solicit and carry on business in their own name or in the name of the manufacturer for a commission, salary, or retainer plus commission. Occasionally, they purchase products by direct payment or financing for resale to their own customers. Export management companies may operate as agents or distributors. The following are some of the disadvantages of using EMCs:

- Manufacturer may lose control over foreign sales. To retain sufficient control, manufacturers should ask for regular reports on marketing efforts, promotion, sales, and so forth. This right to review marketing plans and efforts should be included in the agreement.

- Export management companies that work on commission may lose interest if sales do not come immediately. They may be less interested in new or unknown products and may not provide sufficient attention to small clients.

- Exporters may not learn international business since EMCs do most of the work related to exports.

Despite these disadvantages, EMCs have marketing and distribution contacts overseas and provide the benefit of economies of scale. Export management companies obtain low freight rates by consolidating shipments of several principals. By providing a range of services, they also help manufacturers to concentrate on other areas.

9.3. International Trading Companies (ITCs)

Trading companies are the most traditional and dominant intermediary in many countries. In Japan they date back to the nineteenth century, and in Western countries their origins can be traced back to colonial times. They are also prevalent in many less-developed countries. They are demand driven; that is, they identify the needs of overseas customers and often act as independent distributors linking buyers and sellers to arrange transactions. They buy and sell goods as merchants taking title to the merchandise. Some work on a commission. They may also handle goods on consignment.

In the United States, an ETC is a legally defined entity under the Export Trading Company Act. It is difficult to set up ETCs unless certain special certifications and requirements are met. The U.S. Export Trading Act (ETC) allows bank participation in trading companies, thus facilitating better access to capital and more trading transactions. Antitrust provisions were also relaxed to allow firms to form joint ventures and share the cost of developing foreign markets. Since 2002, more than 186 individual ETCs covering more than 5,000 firms have been certified by the U.S. Department of Commerce. Trade associations often apply for certification for their members. To be effective, ETCs must balance the demands of the markets and the supply of the members (trade association; see International Perspective 5.1).

Trading companies offer services to manufacturers similar to those provided by EMCs. However, there are some differences between the two channels:

- Trading companies offer more services and have more diverse product lines than export management companies. Trading companies are also larger and better financed than EMCs.

- Trading companies are not exclusively restricted to export-import activities. Some are also engaged in production, resource development, and commercial banking. Korean trading companies, such as Daewoo and Hyundai, for example, are heavily involved in manufacturing. Some trading companies, such as Mitsubishi (Japan) and Cobec (Brazil), are affiliated with banks and engaged in extension of traditional banking into commercial fields (Meloan and Graham, 1995).

The disadvantages of ITCs are similar to the ones mentioned for EMCs.

10. Exporters That Buy for Their Overseas Customers

Export Commission Agents (ECAs)

Export commission agents represent foreign buyers such as import firms and large industrial users and seek to obtain products that match the buyer’s preferences and requirements. They reside and conduct business in the exporter’s country and are paid a commission by their foreign clients. In certain cases, ECAs may be foreign government agencies or quasi-government firms empowered to locate and purchase desired goods. They can operate from a permanent office location in supplier countries or undertake foreign government purchasing missions when the need arises. In some countries, the exporter may receive payment from a confirming house when the goods are shipped. The confirming house may also carry out some functions performed by the commission agent or resident buyer (e.g., making arrangements for the shipper). For the exporter, this is an easy way to access a foreign market. There is little credit risk, and the exporter has only to fill the order.

Another variation of the ECA is the resident buyer. The major factor that distinguishes the resident buyer from other ECAs is that in the case of the former, a long-term relationship is established in which the resident buyer not only undertakes the purchasing function for the overseas principal at the best possible price but also ensures timely delivery of merchandise and facilitates principals’ visits to suppliers and vendors. This allows foreign buyers to maintain a close and continuous contact with overseas sources of supply. One disadvantage of using such channels is that the exporter has little control over the marketing of products (Onkvisit and Shaw, 2008).

11. Exporters That Buy and Sell for Their Own Accounts

11.1. Export Merchants

Export merchants purchase products directly from manufacturers, pack and mark them according to their own specifications, and resell to their overseas customers. They take title to the goods and sell under their own names and thus assume all risks associated with ownership. Export merchants generally handle undifferentiated products or products for which brands are not important. In view of their vast organizational networks, they are a powerful commercial entity, dominating trade in certain countries.

When export merchants, after receiving an order, place an order with the manufacturer to deliver the goods directly to the overseas customer, they are called export drop shippers. In this case, the manufacturer is paid by the drop shipper, who, in turn, is paid by the overseas buyer. Such intermediaries are commonly used to export bulky (high-freight), low-unit value products such as construction materials, coal, and lumber.

Another variation of export merchant is the export distributor (located in the exporter’s country). Export distributors have exclusive rights to sell manufacturers’ products in overseas markets. They represent several manufacturers and act as EMCs.

The disadvantage of export merchants as export intermediaries relates to lack of control over marketing, promotion, or pricing.

11.2. Cooperative Exporters (CEs)

These are manufacturers or service firms that sell the products of other companies in foreign markets along with their own (Ball et al., 2013). This generally occurs when a company has a contract with an overseas buyer to provide a wide range of products or services. Often, the company may not have all the products required under the contract and so turns to other companies to provide the remaining products. The company (providing the remaining products) could sell its products without incurring export marketing or distribution costs. This helps small manufacturers that lack the ability/resources to export. This channel is often used to export products that are complementary to those of the exporting firm. A good example of this is the case of a heavy-equipment manufacturer that wants to fill the demand of its overseas customers for water-drilling equipment. The heavy-equipment company exports the drilling equipment along with its product to its customers (Sletten, 1994). Companies engage in cooperative exporting in order to broaden the product lines they offer to foreign markets or to bolster decreasing export sales. In the 1980s, for example, the French chemical company Rhone-Poutenc sold products of several manufacturers through its extensive global sales network.

11.3. Export Cartels

These are organizations of firms in the same industry that exist for the sole purpose of marketing their products overseas. They include the Webb Pomerene associations (WPAs) in the United States, as well as certain export cartels in Japan. The WPAs are exempted from antitrust laws under the U.S. Export Trade Act of 1918 and are permitted to set prices, allocate

orders, sell products, negotiate, and consolidate freight, as well as arrange shipment. There are WPAs in various areas such as pulp, movies, and sulphur. Webb Pomerene associations are not permitted for services and the arrangement is not suitable for differentiated products because a common association label often replaces individual product brands. In addition to member firms’ loss of individual identity, WPAs are vulnerable to lack of group cohesion, similar to other cartels, which undermines their effectiveness. Under the Export Trade Act, the only requirement to operate as a WPA is that the association must file with the Federal Trade Commission within thirty days after formation.

12. Direct Channels

A company can use different avenues to sell its product overseas by employing the direct- channel structure. Direct exporting provides more control over the export process, potentially higher profits, and a closer relationship to the overseas buyer and the marketplace (Table 5.1). However, the firm needs to devote more time, personnel, and other corporate resources than in the case of indirect exporting.

13. Direct Marketing from the Home Country

A firm may sell directly to a foreign retailer or end user, and this is often accomplished through catalog sales or traveling sales representatives who are domestic employees of the exporting firm. Such marketing channels are a viable alternative for many companies that sell books, magazines, housewares, cosmetics, travel, and financial services. Foreign end users include foreign governments and institutions such as banks, schools, hospitals, or businesses. Buyers can be identified at trade shows, through international publications, and so on. If products are specifically designed for each customer, company representatives are more effective than agents or distributors. The growing use of the Internet is also likely to dramatically increase the sale of products and/or services directly to the retailer or end user. For example, Amazon.com has become one of the biggest bookstores in the United States, with more than 2.5 million titles. Its books are sold through the Internet. Direct sales can also be undertaken through foreign sales branches or subsidiaries. A foreign sales branch handles all aspects of the sales distribution and promotion, displays manufacturer’s product lines, and provides services. The foreign sales subsidiary, although similar to the branch, has broader responsibilities. All foreign orders are channeled through the subsidiary, which subsequently sells to foreign buyers. Sales subsidiaries are often used for lucrative markets with growth potential or products with high intellectual-property content, as well as those that require sophisticated training and after-sales service. This approach may raise issues of transfer pricing.

Direct marketing is also used when the manufacturer or retailer desires to increase its revenues and profits while providing its products or services at a lower cost. The firm can also provide better product support services and further enhance its image and reputation.

A major problem with direct sales to consumers results from duty and clearance problems. A country’s import regulations may prohibit or limit the direct purchase of merchandise from overseas. Thus, it is important to evaluate a country’s trade regulations before orders are processed and effected.

14. Marketing through Overseas Agents and Distributors

14.1. Overseas Agents

Overseas agents are independent sales representatives of various noncompeting suppliers. They are residents of the country or region where the product is sold and usually work on a commission basis, pay their own expenses, and assume no financial risk or responsibility. Agents rarely take delivery of and never take title to goods and are authorized to solicit purchases within their marketing territory and to advise firms on orders placed by prospective purchasers. The prices to be charged are agreed upon between the exporters and the overseas customers. Overseas agents usually do not provide product support services to customers. Agency agreements must be drafted carefully so as to clearly indicate that agents are not employees of the exporting companies because of potential legal and financial implications, such as payment of benefits upon termination. In some countries, agents are required to register with the government as commercial agents.

Overseas agents are used when firms intend to (1) sell products to small markets that do not attract distributor interest; (2) market to distinct individual customers (custom made for individuals or projects); (3) sell heavy equipment, machinery, or other big-ticket items that cannot be easily stocked; or (4) solicit public or private bids. Firms deal directly with the customers (after agents inform the firms of the orders) with respect to price, delivery, sales, service, and warranty bonds. Given their limited role, agents are not required to have extensive training or to make a substantial financial commitment. They are valuable for their personal contacts and intelligence and help reach markets that would otherwise be inaccessible. The major disadvantages of using agents are these: (1) There may be legal and financial problems in the event of termination (local laws in many countries discriminate against alien firms [principals] in their contractual relationships with local agents); (2) firms assume the attendant risks and responsibilities, ranging from pricing and delivery to sales and services including collections; and (3) agents have limited training and knowledge about the product, and this may adversely impact product sales.

14.2. Overseas Distributors

These are independent merchants that import products for resale and are compensated by the markup they charge their customers. Overseas distributors take delivery of and title to the goods and have contractual arrangements with the exporters as well as the customers. No contractual relationships exist between the exporters and the customers, and the distributors may not legally obligate exporters to third parties. Distributors may be given exclusive representation for a certain territory, often in return for agreeing not to handle competing merchandise. Certain countries require the registration and approval of distributors (and agents) as well as the representation agreement.

Distributors, unlike agents, take possession of goods and also provide the necessary pre- and postsales services. They carry inventory and spare parts and maintain adequate facilities and personnel for normal service operations. They are responsible for advertising and promotion. Some of the disadvantages of using distributors are: (1) loss of control over marketing and pricing (they may price the product too high or too low); (2) limited access to or feedback from customers, (3) limited opportunity to acquire international business know-how and to learn about developments in foreign markets; and (4) dealer protection legislation in many countries that may make it difficult and expensive to terminate relationships with distributors.

15. Selecting the Right Channel

No single distribution channel may be appropriate for a product in all markets. The choice is often based on a market-by-market basis. Here are some relevant points to consider:

- A firm may use direct channel for its lucrative markets or markets where it has some internal strength and experience. It will use indirect channels for unfamiliar, small, or risky markets.

- A firm may use both channels if it has different product lines with different customer profiles. It can use direct channels for the product in which it has a good network of resources and customers and use indirect channels such as cooperative exporting for other product lines where certain advantages do not exist.

- Indirect channel options should not be ignored just because the firm has long-term plans to go direct. Early indirect entry could facilitate the product’s success (when it goes direct) if good product image and customer support have been created by the indirect partner.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

Im now not certain the place you’re getting your info, however great topic. I needs to spend a while finding out more or working out more. Thank you for magnificent info I used to be looking for this info for my mission.