Advertising can be a cost-effective way to disseminate messages, whether to build a brand preference or to educate people. Even in today’s challenging media environment, good ads can pay off. GEICO has succeeded by keeping both its ad campaigns and their executions fresh.1 2 [1]

GEICO GEICO has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on TV advertising. Has it been worth it? Warren Buffet, chairman and CEO of GEICO’s parent company Berkshire Hathaway, thinks so. GEICO has more than quintupled its revenue over the past decade, from slightly under $3 billion in 1998 to more than $17 billion in 2013—making it the fastest-growing auto insurance company in the United States. The company sells directly to consumers with a basic message, “15 Minutes Could Save You 15% or More on Your Car Insurance.” Partnering with The Martin Agency, GEICO has run a series of highly creative and award-winning ad campaigns to emphasize different aspects of the brand. Four ran concurrently in 2014. TV ads featuring the Cockney-speaking Gecko lizard spokes-character reinforce GEICO’s brand image as credible and accomplished. The “Happier Than” campaign comes up with exaggerated situations to describe how happy GEICO customers are, such as a camel on Wednesday (hump day) or Dracula volunteering at a blood drive. A third campaign featuring Maxwell, a talking pig, focuses on specific products and service features. The fourth campaign, “Did You Know,” starts with a person commenting on the company’s famous 15-minute slogan to a companion, who replies, “Everyone knows that.” The first speaker then tries to save face with a twist on some other conventional wisdom, such as that Pinocchio was a poor motivational speaker or Old McDonald was a really bad speller. The multiple campaigns complement each other and build on each other’s success; the company dominates the TV airwaves with so many varied car insurance messages that competitors’ ads are lost.

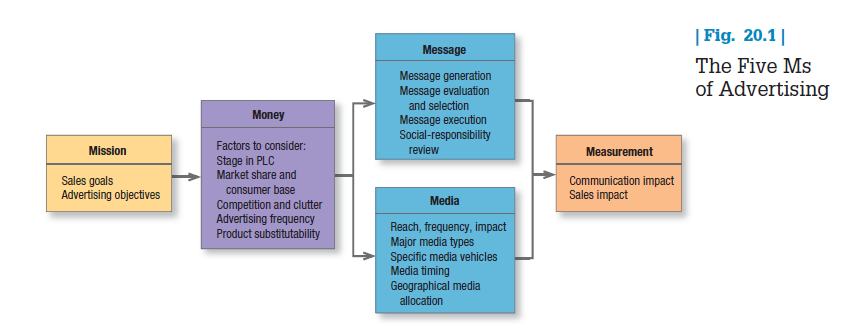

In developing an advertising program, marketing managers must always start by identifying the target market and buyer motives. Then they can make the five major decisions known as “the five Ms”:

- Message: What should the ad campaign say?

- Media: What media should we use?

- Measurement: How should we evaluate the results?

These decisions are summarized in Figure 20.1 and described in the following sections.

1. SETTING THE ADVERTISING OBJECTIVES

Advertising objectives must flow from earlier decisions about target market, brand positioning, and the marketing program. An advertising objective (or goal) is a specific communications task and achievement level to be accomplished with a specific audience in a specific period of time:4

To increase among 30 million homemakers who own automatic washers the number who identify brand X as a low-sudsing detergent, and who are persuaded that it gets clothes cleaner, from 10 percent to 40 percent in one year.

We classify advertising objectives according to whether they aim to inform, persuade, remind, or reinforce. These goals correspond to stages in the hierarchy-of-effects model discussed in Chapter 19.

- Informative advertising aims to create brand awareness and knowledge of new products or new features of existing products.5 Consumer packaged goods companies like Colgate, General Mills, and Unilever will often focus on key product benefits.

- Persuasive advertising aims to create liking, preference, conviction, and purchase of a product or service. Some persuasive advertising is comparative advertising, which explicitly compares the attributes of two or more brands, such as the Chrysler TV ad for the Dodge Ram that asks, “What if you were to take away horsepower, torque and warranty coverage from a Ram? Well, youd end up with a Ford F-150.”6 Comparative advertising works best when it elicits cognitive and affective motivations simultaneously and when consumers are processing advertising in a detailed, analytical mode.7

- Reminder advertising aims to stimulate repeat purchase of products and services. Expensive, four-color Coca-Cola ads in magazines remind people to purchase Coca-Cola.

- Reinforcement advertising aims to convince current purchasers they made the right choice. Automobile ads often depict satisfied customers enjoying special features of their new car.

The advertising objective should emerge from a thorough analysis of the current marketing situation. If the product class is mature, the company is the market leader, and brand usage is low, the objective is to stimulate more usage. If the product class is new, the company is not the market leader, and the brand is superior to the leader, the objective is to convince the market of the brand’s superiority.

2. DECIDING ON THE ADVERTISING BUDGET

How does a company know it’s spending the right amount? Although advertising is treated as a current expense, part of it is really an investment in building brand equity and customer loyalty. When a company spends $5 million on capital equipment, it can call the equipment a five-year depreciable asset and write off only one-fifth of the cost in the first year. When it spends $5 million on advertising to launch a new product, however, it must write off the entire cost in the first year, reducing its reported profit, even if the benefits will persist for many years to come.

FACTORS AFFECTING BUDGET DECISIONS Here are five specific factors to consider when setting the advertising budget:8

- Stage in the product life cycle—New products typically merit large advertising budgets to build awareness and gain consumer trial. Established brands usually are supported by lower advertising budgets, measured as a ratio to sales.

- Market share and consumer base—High-market-share brands usually require less advertising expenditure as a percentage of sales to maintain share. Building share by increasing market size requires larger expenditures.

- Competition and clutter—In a market with a large number of competitors and high advertising spending, a brand must advertise more heavily to be heard. Even advertisements not directly competitive to the brand create clutter and a need for heavier advertising.

- Advertising frequency—The number of repetitions needed to put the brand’s message across to consumers has an obvious impact on the advertising budget.

- Product substitutability—Brands in less-differentiated or commodity-like product classes (beer, soft drinks, banks, and airlines) require heavy advertising to establish a unique image.

ADVERTISING ELASTICITY The predominant response function for advertising is often concave but can be S-shaped. When it is S-shaped, some positive amount of advertising is necessary to generate any sales impact, but sales increases eventually flatten out.9

One classic study found that increasing the TV advertising budget had a measurable effect on sales only half the time. The success rate was higher for new products and line extensions than for established brands and when there were changes in copy or in media strategy (such as an expanded target market). When advertising increased sales, its impact lasted up to two years after peak spending. Long-term incremental sales were approximately double those in the first year of an advertising spending increase.10

Other research reinforces these conclusions. In a 2004 IRI study of 23 brands, advertising often didn’t increase sales for mature brands or categories in decline. A review of academic research found that advertising elasticities were estimated to be higher for new (.3) than for established (.1) products.11 Research has also found that what you say (ad copy) is more important than the number of times you say it (ad frequency).12

3. DEVELOPING THE ADVERTISING CAMPAIGN

Advertisers employ both art and science to develop the message strategy or positioning of an ad—what it attempts to convey about the brand—and its creative strategy—how it expresses the brand claims. They use three steps: message generation and evaluation, creative development and execution, and social-responsibility review.

MESSAGE GENERATION AND EVALUATION Advertisers are always seeking “the big idea” that connects with consumers rationally and emotionally, distinguishes the brand from competitors, and is broad and flexible enough to translate to different media, markets, and time periods. Fresh insights are important for creating unique appeals and position.13

GOT MILK? After a 20-year decline in milk consumption among Californians, in 1993 milk processors from across the state formed the California Milk Processor Board (CMPB) with one goal in mind: to get people to drink more milk. The ad agency commissioned by the CMPB, Goodby, Silverstein & Partners, developed a novel approach to pitching milk’s benefits. Research had shown most consumers already believed milk was good for them. So the campaign reminded them of the inconvenience of running out of it, which became known as the “milk deprivation” strategy. The “got milk?” tagline reminded consumers to make sure they had enough milk in their refrigerators. A year after the launch, sales volume had increased 1.07 percent. In 1995, the “got milk?” campaign was licensed to the National Dairy Board. In 1998, the National Fluid Milk Processor Education Program, which had been using the “milk mustache” campaign since 1994 to boost sales, bought the rights to the “got milk?” tagline, which it used for the next 15 years. The “got milk?” campaign paid strong dividends by halting the decline in sales of milk in California, even more than a decade after its launch.

A good ad normally focuses on one or two core selling propositions. As part of refining the brand positioning, the advertiser should conduct market research to determine which appeal works best with its target audience and then prepare a creative brief, typically one or two pages. This is an elaboration of the positioning strategy and includes considerations such as key message, target audience, communications objectives (to do, to know, to believe), key brand benefits, supports for the brand promise, and media.

How many ad themes should the advertiser create before choosing one? The more themes explored, the higher the probability of finding an excellent one. Fortunately, an ad agency’s creative department can inexpensively compose many alternatives in a short time by drawing still and video images from computer files. Marketers can also cut the cost of creative dramatically by using consumers as their creative team, a strategy sometimes called “open sourcing” or “crowdsourcing.”14

CONSUMER-GENERATED ADVERTISING consumer-generated ads was Converse, whose award-winning campaign “Brand Democracy” used films created by consumers in a series of TV and Web ads. H. J. Heinz ran a “Top This TV Challenge,” inviting the public to create the next commercial for its Heinz Ketchup brand and win $57,000. More than 6,000 submissions and 10 million online views resulted, and sales rose more than 13 percent year over year. In addition to creating ads, consumers can help disseminate advertising. A UK “Life’s for Sharing” ad for T-Mobile in which 400 people break into a choreographed dance routine in the Liverpool Street Station was shown exactly once on the Celebrity Big Brother television show, but it was watched more than 15 million times online when word about it spread via e-mail messages, blogs, and social networks. McDonald’s similarly ran a popular user-generated campaign for its 2012 London Olympics sponsorship. Academic researchers have shown that consumer-generated ads can create more emotional and personal appeal, be deemed more credible and authentic, and lead to higher levels of brand loyalty and purchase intentions among viewers than company-produced ads, at least as long as consumers are not overly skeptical.

Although entrusting consumers with a brand’s marketing effort can be pure genius, it can also be a regrettable failure. When Kraft sought a hip name for a new flavor of its iconic Vegemite product in Australia, it labeled the first 3 million jars “Name Me” to enlist consumer support. From 48,000 entries, however, the marketer selected one that was thrown in as a joke—iSnack 2.0—and sales plummeted. The company had to pull iSnack jars from the shelves and start from scratch in a more conventional fashion, choosing the new name Cheesybite.15

CREATIVE DEVELOPMENT AND EXECUTION The ad’s impact depends not only on what it says but, often more important, on how it says it. Creative execution can be decisive.16 Every advertising medium has advantages and disadvantages. Here, we briefly review television, print, and radio advertising media.

Television Ads Television is generally acknowledged as the most powerful advertising medium and reaches a broad spectrum of consumers at low cost per exposure. TV advertising has two particularly important strengths. First, it can vividly demonstrate product attributes and persuasively explain their corresponding consumer benefits. Second, it can dramatically portray user and usage imagery, brand personality, and other intangibles.

Because of the fleeting nature of the ad, however, and the distracting creative elements often found in it, product-related messages and the brand itself can be overlooked. Moreover, the high volume of nonprogramming material on television creates clutter that makes it easy for consumers to ignore or forget ads. Nevertheless, properly designed and executed TV ads can still be a powerful marketing tool that improves brand equity, sales, and profits. In the highly competitive insurance category, advertising can help a brand to stand out.17

AFLAC Aflac, the largest supplier of supplemental insurance, was relatively unknown until a highly creative ad campaign made it one of the most recognized brands in recent history. (Aflac stands for American Family Life Assurance Company.) Created by the Kaplan Thaler ad agency, the lighthearted campaign features an irascible duck incessantly squawking the company’s name, “Aflac!” while consumers or celebrities discuss its products. The duck’s frustrated bid for attention appealed to consumers. Sales were up 28 percent in the first year the duck aired, and name recognition went from 13 percent to 91 percent. Aflac has stuck with the duck in its advertising, even incorporating it into its corporate logo in 2005. Social media have allowed marketers to further develop the duck’s personality—it has 515,000 Facebook fans and counting. The Aflac duck is not just a U.S. phenomenon. It also stars in Japanese TV ads—with a somewhat brighter disposition—where it has been credited with helping drive sales in Aflac’s biggest market.

Radio Ads Radio is a pervasive medium: Ninety-three percent of all U.S. citizens age 12 and older listen daily and for about 20 hours a week on average, numbers that have held steady in recent years. Much radio listening occurs in the car and out of home. To be successful, radio networks are going multi-platform with a strong digital presence to allow listeners to tune in anytime, anywhere.

Perhaps radio’s main advantage is flexibility—stations are very targeted, ads are relatively inexpensive to produce and place, and short closings for scheduling them allow for quick response. Radio can engage listeners through a combination of popular brands, local presence, and strong personalities.21 It is a particularly effective medium in the morning; it can also let companies achieve a balance between broad and localized market coverage.

Radio’s obvious disadvantages are its lack of visual images and the relatively passive nature of the consumer processing that results. Nevertheless, radio ads can be extremely creative. Clever use of music, sound, and other creative devices can tap into the listener’s imagination to create powerfully relevant images. Here is an example:22

MOTEL 6 Motel 6, the nation’s largest budget motel chain, was founded in 1962 when the “6” stood for $6 a night. After its business fortunes hit bottom in 1986 with an occupancy rate of only 66.7 percent, the company made a number of marketing changes, including the launch of humorous 60-second radio ads featuring folksy writer Tom Bodett delivering the clever tagline “We’ll Leave the Light on for You.” Named one of Advertising Age’s Top 100 Ad Campaigns of the Twentieth Century, the campaign continues to receive awards, including the 2009 Radio Mercury Awards grand prize for an ad called “DVD.” In this ad, Bodett introduces the “DVD version” of his latest commercial, utilizing his trademark selfdeprecating style to provide “behind the scenes” commentary on his own performance. Still going strong, the campaign is credited with a rise in occupancy and a revitalization of the brand that continues to this day.

LEGAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES To break through clutter, some advertisers believe they have to push the boundaries of what advertising consumers are used to seeing. They must be sure, however, not to overstep social and legal norms or offend the general public or ethnic, racial, or special-interest groups.

A substantial body of U.S. laws and regulations governs advertising. Advertisers must not make false claims, use false demonstrations, or create ads with the capacity to deceive, even if no one is actually deceived. A floor wax advertiser can’t say the product gives six months’ protection unless it does so under typical conditions, and a diet bread baker can’t say its product has fewer calories simply because its slices are thinner. The challenge is telling the difference between deception and “puffery”—simple exaggerations that are not meant to be believed and that are permitted by law. “Marketing Insight: Off-Air Ad Battles” describes a few recent legal disputes about what should be permissible in a brand’s advertising.

Sellers in the United States are legally obligated to avoid bait-and-switch advertising that attracts buyers under false pretenses. Suppose a seller advertises a sewing machine at $149. When consumers try to buy the advertised machine, the seller cannot then refuse to sell it, downplay its features, show a faulty one, or promise unreasonable delivery dates in order to switch the buyer to a more expensive machine.23

Advertising can play a more positive broader social role. The Ad Council is a nonprofit organization that uses top-notch industry talent to produce and distribute public service announcements for nonprofits and government agencies. From its early origins with “Buy War Bonds” posters, the Ad Council has tackled innumerable pressing social issues through the years, from drunk driving to AIDS prevention to its current focus on domestic violence.

4. MARKETING MEMO Print Ad Evaluation Criteria

In judging the effectiveness of a print ad, marketers should be able to answer yes to the following questions about its execution:

- Is the message clear at a glance? Can you quickly tell what the ad is all about?

- Is the benefit in the headline?

- Does the illustration support the headline?

- Does the first line of the copy support or explain the headline and illustration?

- Is the ad easy to read and follow?

- Is the product easily identified?

- Is the brand or sponsor clearly identified?

Source: Adapted from Scott C. Purvis and Philip Ward Burton, Which Ad Pulled Best, 9th ed. (Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books, 2002).

5. MARKETING INSIGHT Off-Air Ad Battles

In a highly competitive environment, perhaps it is not surprising that not everyone sees eye to eye on what is suitable advertising. Here are two notable recent disputes.

Splenda

Splenda’s tagline for its artificial sweetener was “Made from sugar, so it tastes like sugar,” with “but it’s not sugar” in small writing almost as an afterthought. McNeil Nutritionals, Splenda’s manufacturer, does begin production of Splenda with pure cane sugar but burns it off in the manufacturing process.

Merisant, maker of Equal, claimed that Splenda’s advertising confused consumers who were likely to conclude that a product “made from sugar” is healthier than one made from aspartame, Equal’s main ingredient. A document from McNeil’s own files and used in court says consumers’ perception of Splenda as “not an artificial sweetener” was one of the biggest triumphs of the company’s marketing campaign, which began in 2003.

Splenda became the runaway leader in the sugar-substitute category with 60 percent of the market, leaving roughly 14 percent each to Equal and Sweet’N Low. Although McNeil eventually agreed to settle the lawsuit and pay Merisant an undisclosed but “substantial” award (and change its advertising), it may have been too late to change consumers’ perception of Splenda as something sugary and sugar-free.

POM Wonderful

In May 2012, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a “cease- and-desist” order against POM Wonderful, saying the company had spread deceptive claims in print publications and billboards and online that its POM pomegranate juice could treat or prevent erectile dysfunction, prostate cancer, and heart disease. The ruling came after two years of legal back and forth. Oddly, however, POM appeared to declare victory, running a full-page ad in the New York Times lauding the fact that the ruling did not force it to seek re-approval from the Food and Drug Administration (as drug companies must do). A later appeal was rejected as the FTC continued to rule against POM ads using headlines such as “Cheat Death” without stronger evidence.

POM was not the only one to run into trouble over pomegranates. Welch’s settled two class-action suits for $30 million because labels on its 100% Juice White Grape Pomegranate Flavored 3 Juice Blend claimed more pomegranate than it really had—only 1 ounce in a 64-ounce bottle.

Sources: Sarah Hills, “McNeil and Sugar Association Settle Splenda Dispute,” Food Navigator-usa.com, www.foodnavigator-usa.com, November 18, 2008; James P Miller, “Bitter Sweets Fight Ended,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 2007; Avery Johnson, “How Sweet It Isn’t: Maker of Equal Says Ads for J&J’s Splenda Misled; Chemistry Lesson for Jurors,” Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2007; “In Lawsuit Brought by POM Wonderful, a Federal Jury Finds Juice Maker Welch’s Intentionally Misled Consumers,” Reuters, September 15, 2010; Ily Goyanes, “Welch’s Lies about Its Juice, Pays $30 Million and No One Notices,” Miami New Times, February 24, 2011; Charlie Minato, “POM Wonderful Is Bragging about Loss to FTC in Full Page Ads in the NY Times,” Business Insider, May 24, 2012; Alicia Mundy, “FTC Bars Pom Juice’s Health Claims,” Wall Street Journal, January 16, 2013. For a discussion of the possible role of corrective advertising, see Peter Darke, Laurence Ashworth, and Robin J. B. Ritchie, “Damage from Corrective Advertising: Causes and Cures,” Journal of Marketing 72 (November 2008), pp. 81-97.

6. CHOOSING MEDIA

After choosing the message, the advertiser’s next task is to select media to carry it. The steps here are deciding on desired reach, frequency, and impact; choosing among major media types; selecting specific media vehicles; and setting media timing and geographical allocation. Then the marketer evaluates the results of these decisions.

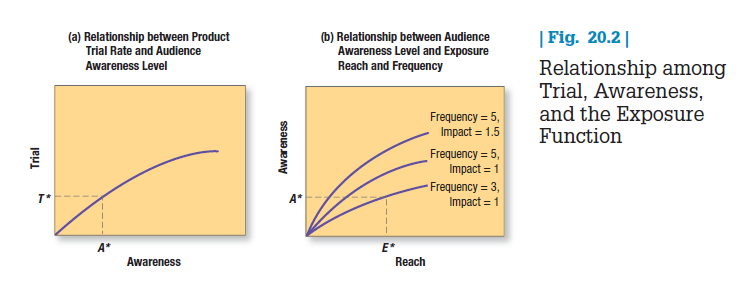

REACH, FREQUENCY, AND IMPACT Media selection is finding the most cost-effective media to deliver the desired number and type of exposures to the target audience. What do we mean by the desired number of exposures? The advertiser seeks a specified advertising objective and response from the target audience—for example, a target level of product trial. This level depends on, among other things, level of brand awareness. Suppose the rate of product trial increases at a diminishing rate with the level of audience awareness, as shown in Figure 20.2(a). If the advertiser seeks a product trial rate of T *, it will be necessary to achieve a brand awareness level of A*.

The next task is to find out how many exposures, E *, will produce a level of audience awareness of A*. The effect of exposures on audience awareness depends on the exposures’ reach, frequency, and impact:

- Reach (R). The number of different persons or households exposed to a particular media schedule at least once during a specified time period

- Frequency (F). The number of times within the specified time period that an average person or household is exposed to the message

- Impact (I). The qualitative value of an exposure through a given medium (thus, a food ad should have a higher impact in Bon Appetit than in Fortune magazine)

Figure 20.2(b) shows the relationship between audience awareness and reach. Audience awareness will be greater the higher the exposures’ reach, frequency, and impact. There are important trade-offs here. Suppose the planner has an advertising budget of $1,000,000 and the cost per thousand exposures of average quality is $5. This means 200,000,000 exposures ($1,000,000 [$5/1,000]). If the advertiser seeks an average exposure frequency of 10, it can reach 20,000,000 people (200,000,000 10) with the given budget. But if the advertiser wants higher-quality media costing $10 per thousand exposures, it will be able to reach only 10,000,000 people unless it is willing to lower the desired exposure frequency.

The relationship between reach, frequency, and impact is captured in the following concepts:

- Total number of exposures (E). This is the reach times the average frequency; that is, E = R x F, also called the gross rating points (GRP). If a given media schedule reaches 80 percent of homes with an average exposure frequency of 3, the media schedule has a GRP of 240 (80 x 3). If another media schedule has a GRP of 300, it has more weight, but we cannot tell how this weight breaks down into reach and frequency.

- Weighted number of exposures (WE). This is the reach times average frequency times average impact, that is WE = R x F x I.

Reach is most important when launching new products, flanker brands, extensions of well-known brands, and infrequently purchased brands or when going after an undefined target market. Frequency is most important where there are strong competitors, a complex story to tell, high consumer resistance, or a frequent- purchase cycle.24

A key reason for repetition is forgetting. The higher the forgetting rate associated with a brand, product category, or message, the higher the warranted level of repetition. However, advertisers should not coast on a tired ad but insist on fresh executions by their ad agency.25

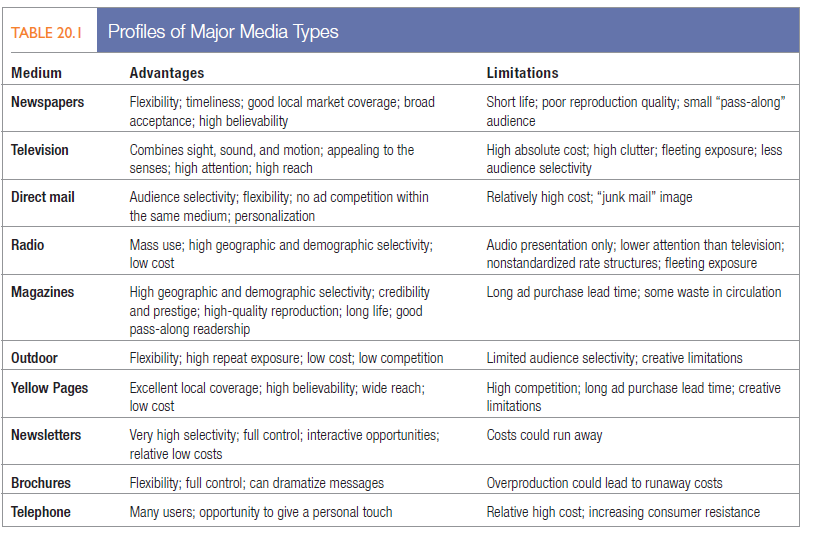

CHOOSING AMONG MAjOR MEDiA TYPES The media planner must know the capacity of the major advertising media types to deliver reach, frequency, and impact. The major advertising media along with their costs, advantages, and limitations are profiled in Table 20.1. Media planners make their choices by considering factors such as target audience media habits, product characteristics, message requirements, and cost.

PLACE ADVERTISING OPTIONS Place advertising, or out-of-home advertising, is a broad category including many creative and unexpected forms to grab consumers’ attention where they work, play, and, of course, shop. Popular options include billboards, public spaces, product placement, and point of purchase.

Billboards Billboards use colorful, digitally produced graphics, backlighting, sounds, movement, and unusual— even 3D—images.26 In New York, manhole covers have been reimagined as steaming cups of Folgers coffee; in Belgium, eBay posted “Moved to eBay” stickers on empty storefronts; and in Germany, imaginary workers toiling inside vending machines, ATMs, and photo booths were justification for a German job-hunting Web site to proclaim, “Life Is Too Short for the Wrong Job.”27

New “Eyes On” measurement techniques allow marketers to better understand who has seen their outdoor ads.28 A strong creative message can make all the difference. Chang Soda in Bangkok had enough money in its budget for only one digital billboard. To maximize impact, it built a giant bubbling bottle onto the billboard to illustrate the product’s carbonation. Word-of-mouth buzz quintupled bottle sales from 200,000 to 1 million.29

Public Spaces Ads are appearing in such unconventional places as movie screens, airplane bodies, and fitness equipment, as well as in classrooms, sports arenas, office and hotel elevators, and other public places.30 Transit ads on buses, subways, and commuter trains have become a valuable way to reach working women. “Street furniture”— bus shelters, kiosks, and public areas—is another fast-growing option.

Advertisers can buy space in stadiums and arenas and on garbage cans, bicycle racks, parking meters, airport luggage carousels, elevators, gasoline pumps, the bottom of golf cups and swimming pools, airline snack packages, and supermarket produce in the form of tiny labels on apples and bananas. They can even buy space in toilet stalls and above urinals, which office workers visit an average of three to four times a day for roughly four minutes per visit.31

Product Placement Marketers pay $100,000 to $500,000 so their products will make cameo appearances in movies and on television.32 Sometimes such product placements are the result of a larger network advertising deal, but small product-placement shops also maintain ties with prop masters, set designers, and production executives.

Some firms get product placement at no cost. Nike does not pay to be in movies but often supplies shoes, jackets, bags, and so on. Increasingly, products and brands are being woven directly into the story, as when a new iPad for the gadget-loving dad of Modern Family became the story arc of a whole episode. In some cases, however, brands pay for the rights to appear in a movie, as with Skyfall.33

SKYFALL With Skyfall, the 23rd film in the franchise, Heineken reportedly paid almost $40 million for the rights to have James Bond drink its beer instead of his traditional vodka martini, covering a third of the film’s estimated production budget. Marketers with the most on-screen presence beyond Heineken’s in the film included Adidas, Aston Martin, Audi, Omega, Sony, and Tom Ford. One research firm estimated that brands in the film received more than $7.6 million worth of exposure during its opening weekend. Some brands featured their movie promotion off-screen too. Heineken shot an extravagant 90-second ad featuring an inventive chase on a train that ended with a cameo appearance by Daniel Craig, the British actor currently playing Bond. More than 22 million people viewed the campaign online, and Heineken’s “Crack the Case” promotion invited consumers in major cities to demonstrate their Bond-like skills in a game.

Product placement is not immune to criticism; lawmakers fault its stealth nature, threatening to force more explicit disclosure of participating advertisers.34

Point of Purchase Chapter 18 discussed shopper marketing and in-store marketing efforts. The appeal of point-of-purchase advertising is that consumers make many brand decisions in the store—74 percent according to one study.35

There are many ways to communicate at the point of purchase (P-O-P), including ads on shopping carts, cart straps, aisles, and shelves and in-store demonstrations, live sampling, and instant coupon machines.36 Some supermarkets are selling floor space for company logos and experimenting with talking shelves. Mobile marketing reaches consumers via smart phones when in store. P-O-P radio provides FM-style programming and commercial messages to thousands of food stores and drugstores nationwide. Video screens in some stores, such as Walmart, play TV-type ads.37

WALMART SMART NETWORK Walmart, an in-store advertising pioneer, replaced its original program with a new SMART network in 2008 playing on 27,000 individual screens in its 2,700 stores nationwide. Programming reaches 160 million viewers every four weeks with large welcome screens at the entrance of the store, a category screen in departments, and endcap screens on each aisle. Advertisers pay $325,000 for 30-second spots per two-week cycle in the grocery section and $650,000 per four-week run in the health and beauty department. Five-second ads running every two minutes for two weeks on the welcome screens are $80,000, and 10-second spots running twice every six minutes on the full network cost $50,000 per week. By linking the time when ads were shown and when product sales were made, Walmart can estimate how much ads increase sales by department (from 7 percent in Electronics to 28 percent in Health & Beauty) and by product type (mature items increase 7 percent, seasonal items 18 percent).

EVALUATING ALTERNATE MEDIA Nontraditional media can often reach a very precise and captive audience in a cost-effective manner, with ads anywhere consumers have a few seconds to notice them. The message must be simple and direct. Outdoor advertising, for example, is often called the “15-second sell.” It’s more effective at enhancing brand awareness or brand image than at creating new brand associations.

Unique ad placements designed to break through clutter may also be perceived as invasive and obtrusive, however, especially in traditionally ad-free spaces such as in schools, on police cruisers, and in doctors’ waiting rooms. Nevertheless, perhaps because of their sheer pervasiveness, some consumers seem less bothered by nontraditional media now than in the past. “Marketing Insight: Playing Games with Brands” describes the how brands have become infused in gaming.

The challenge for nontraditional media is demonstrating its reach and effectiveness through credible, independent research. But there will always be room for creativity, as when Intel struck a five-year deal with the famed FC Barcelona soccer team to place its Intel Inside logo on the inside of players’ jerseys, so when they lifted their shirts after scoring a goal, a customary gesture, the logo would appear.38

SELECTING SPECIFIC MEDIA VEHICLES The media planner must choose the most cost-effective vehicles within each chosen media type. The advertiser who decides to buy 30 seconds of advertising on network television can pay $75,000 for a new show, $350,000 for a popular prime-time show such as Sunday Night Football, The Big Bang Theory, or The Voice, or almost $4 million for the Super Bowl.39 These choices are critical: The average cost to produce a national 30-second television commercial is about $300,000,40 so it can cost as much to run an ad once on network TV as to create and produce it to start with! “Marketing Memo: Winning The Super Bowl of Advertising” describes how marketers approach the biggest event on the U.S. sports scene.

Media planners rely on measurement services that estimate audience size, composition, and media cost and then calculate the cost per thousand persons reached. A full-page, four-color ad in Sports Illustrated cost approximately $412,500 in 2014. If Sports Illustrated’s estimated readership was 3 million people, the cost of exposing the ad to 1,000 persons was $13.75. The same ad in People cost approximately $337,400 and reached 3.475 million people—at a lower cost-per-thousand of $9.71.41 Magazines often put together a “reader profile” for their advertisers, describing average readers’ age, income, residence, marital status, and leisure activities.

Marketers need to adjust the cost-per-thousand measure. First, consider audience quality. For a baby lotion ad, a magazine read by 1 million young parents has an exposure value of 1 million; if read by 1 million teenagers, it has an exposure value of almost zero. Second, look at audience-attention probability. Readers of Vogue may pay more attention to ads than do readers of Sports Illustrated. Third is the medium’s editorial quality, meaning its prestige and believability. People are more likely to believe a TV or radio ad when it appears within a program they like. Fourth, consider the value of ad placement policies and extra services, such as regional or occupational editions and lead-time requirements for magazines.

Media planners are using more sophisticated measures of effectiveness and employing them in mathematical models to arrive at the best media mix.42 Many advertising agencies use software programs to select the initial media and make improvements based on subjective factors.

SELECTING MEDIA TIMING AND ALLOCATION In choosing media, the advertiser makes both a macroscheduling and a microscheduling decision. The macroscheduling decision relates to seasons and the business cycle. Suppose 70 percent of a product’s sales occur between June and September. The firm can vary its advertising expenditures to follow the seasonal pattern, to oppose the seasonal pattern, or to be constant throughout the year.

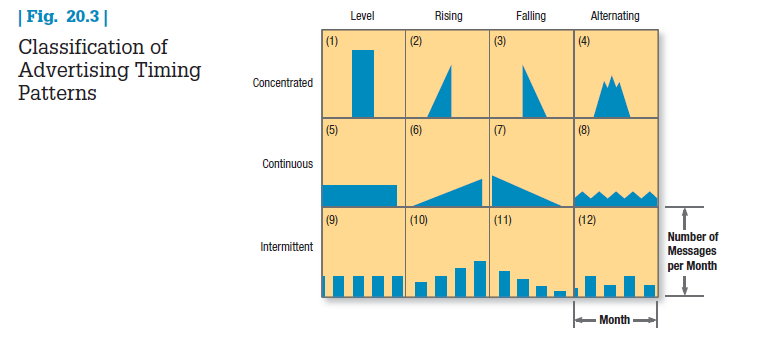

The microscheduling decision calls for allocating advertising expenditures within a short period to obtain maximum impact. Suppose the firm decides to buy 30 radio spots in September. The left side of Figure 20.3 shows that advertising messages for the month can be concentrated (“burst” advertising), dispersed continuously throughout the month, or dispersed intermittently. The top side shows they can be beamed with a level, rising, falling, or alternating frequency.

The chosen pattern should meet the marketer’s communications objectives and consider three factors. Buyer turnover expresses the rate at which new buyers enter the market; the higher this rate, the more continuous the advertising should be. Purchase frequency is the number of times the average buyer buys the product during the period; the higher the purchase frequency, the more continuous the advertising should be. The forgetting rate is the rate at which the buyer forgets the brand; the higher the forgetting rate, the more continuous the advertising should be.

In launching a new product, the advertiser must choose among continuity, concentration, flighting, and pulsing.

- Continuity means exposures appear evenly throughout a given period. Generally, advertisers use continuous advertising in expanding markets, with frequently purchased items, and in tightly defined buyer categories.

- Concentration calls for spending all the advertising dollars in a single period. This makes sense for products with one selling season or related holiday.

- Flighting calls for advertising during a period, followed by a period with no advertising, followed by a second period of advertising activity. It is useful when funding is limited, the purchase cycle is relatively infrequent, or items are seasonal.

- Pulsing is continuous advertising at low levels, reinforced periodically by waves of heavier activity. It draws on the strengths of continuous advertising and flights to create a compromise scheduling strategy. Those who favor pulsing believe the audience will learn the message more thoroughly and at a lower cost to the firm.43

A company must allocate its advertising budget over space as well as over time. It makes “national buys” when it places ads on national TV networks or in nationally circulated magazines. It makes “spot buys” when it buys TV time in just a few markets or in regional editions of magazines. These markets are called areas of dominant influence (ADIs) or designated marketing areas (DMAs). The company makes “local buys” when it advertises in local newspapers, radio, or outdoor sites.

7. MARKETING insight Playing Games with Brands

More than half of U.S. adults and virtually all teens (97 percent) play video games, and about one in five play every day or almost every day. About 40 percent of gamers are women, who prefer puzzles and collaborative games, whereas men seem more attracted to competitive or simulation games. Given this explosive popularity, many advertisers have gotten on board.

A top-notch “advergame” can cost between $100,000 and $500,000 to develop. The game can be played on the sponsor’s corporate homepage, on gaming portals, or even at public locations such as restaurants. Apple Jacks has an advergame on its Web site called Race to the Bowl Rally that targets kids and gives point bonuses for picking up Apple Jacks on the race course. In the M&M Chocolate Factory game, users help the M&M characters make their way through 12 different game levels inside a candy factory and can share content via Facebook and Twitter. Marketers collect valuable customer data upon registration and often seek permission to send e-mail. Among players of a game sponsored by Ford Escape SUV, 54 percent signed up for e-mail.

Marketers are also starring in popular games. Gatorade appears in NBA 2k13, AXE body spray in Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory, and White Castle in Homefront. Mainstream marketers such as Apple, Procter & Gamble, Toyota, and Visa have all developed games. By integrating branded structures into a city-building game called We City for mobile devices, Century 21 increased brand awareness with key 25- to 34-year-old targets.

Research suggests gamers are fine with ads and the way they affect the game experience. One study showed 70 percent of gamers felt dynamic in-game ads “contributed to realism,” “fit the games” in which they served, and looked “cool.”

Sources: Lauren Johnson, “Mars Ups Brand-Building Efforts through Mobile Game,” Mobile Marketer, December 12, 2012; Molly Soat, “Virtual Development,” Marketing News, May 31,2103; Michelle Kung, “We Interrupt This Video Game for a Word from Our Sponsor,” Wall Street Journal, June 13, 2011; www.applejacks. com/games/race-to-the-rally; Amanda Lenhart, “Video Games: Adults Are Players Too,” Pew Internet & American Life Project, www.pewresearch.org, December 7, 2008; Erika Brown, “Game On!” Forbes, July 24, 2006, pp. 84-86.

8. MARKETING MEMO Winning The Super Bowl of Advertising

The Super Bowl attracts the largest audience on television; 111 million viewers watched Fox’s broadcast in 2014. With an audience that large, a 30-second ad slot sold for a pricey $4 million.

From the first game in 1975, Super Bowl advertising has grown in importance as football has become more popular. Apple’s iconic “1984” spot launching Macintosh computers featured a futuristic Orwellian world shot by famed film director Ridley Scott and ushered in a new world of Super Bowl advertising. Appearing just once during a one-sided victory by the Los Angeles Raiders over the Washington Redskins, the ad became the talk of the game, and marketers and ad agencies began to look at advertising in the game in a more ambitious way.

The introduction of the USA Today ad meter in 1989 focused even more consumer attention on the ads and their entertainment value. While the normal rate of audience tune-out during a commercial is 4 percent, Super Bowl ads average less than 1 percent. They have been shown to be more memorable and likable than typical ads and can even give a firm’s stock price a bump.

Many Super Bowl ads now have a new purpose: to create curiosity and interest so consumers will go online and engage in social media and word of mouth to uncover more detailed information. The most popular—like a Honda CR-V ad with Matthew Broderick spoofing his Ferris Bueller film role and a VW ad with a young kid playing Darth Vader—drew tens of millions of YouTube views. Increasingly, ads are released online before the game as firms attempt to maximize their social media and PR power.

Given the large and diverse audience, many Super Bowl advertisers try to please as many people as possible, employing cute babies, playful animals, and slapstick humor. But Paul Venables, a Super Bowl ad veteran, recommends being as clear as possible about the strategic goal sought. Is it to generate social media buzz, online product searches, or store or dealer visits? As he says, “There are a million metrics and you have to decide what you are measuring.” Another agency leader, Brad Kay, advocates a holistic approach, leveraging the high-profile TV spot to create more conversion opportunities online.

Sources: Ellen Killoran, “Super Bowl Ads 2014: What Does $4 Million Really Buy You?,” International Business Times, January 30, 2014; Jin-Woo Kim, Traci H. Freling, and Douglas B. Grisaffe, “The Secret Sauce for Super Bowl Advertising,” Journal of Advertising Research 53 (June 2013), pp. 134-49; Noreen O’Leary, “How to Win the Super Bowl,” Adweek, January 28, 2013; Lucia Moses, “Ad Play,” Adweek, January 28, 2013; Alex Konrad, “5 Ways the Super Bowl Ad Playbook Has Changed,” www.tech .fortune.cnn.com, February 2, 2012; Michael Learmonth, “How USA Today’s Ad Meter Broke Super Bowl Advertising,” Advertising Age, January 30, 2012; Bruce Horovitz, “Super Bowl Marketers Go All Out to Create Hype, Online Buzz,” USA Today, February 8, 2010.

9. EVALUATING ADVERTISING EFFECTIVENESS

Most advertisers try to measure the communication effect of an ad—that is, its potential impact on awareness, knowledge, or preference. They would also like to measure its sales effect.

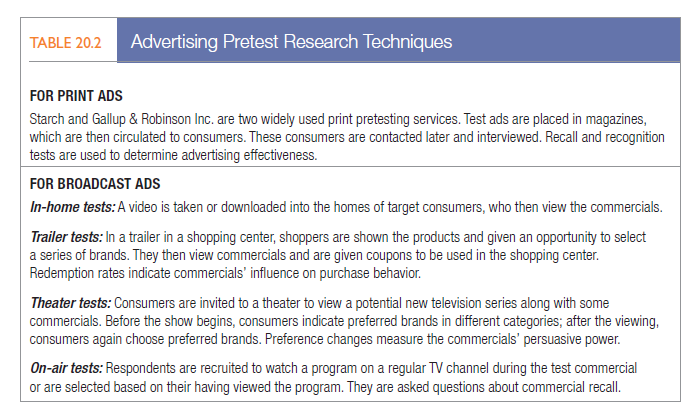

COMMUNICATION-EFFECT RESEARCH Communication-effect research, called copy testing, seeks to determine whether an ad is communicating effectively. Marketers should perform this test both before an ad is put into media and after it is printed or broadcast. Table 20.2 describes some specific advertising pretest research techniques.

Pretest critics maintain that agencies can design ads that test well but may not necessarily perform well in the marketplace. Proponents maintain that useful diagnostic information can emerge and that pretests should not be used as the sole decision criterion anyway. Widely acknowledged as one of the best advertisers around, Nike is known for doing very little ad pretesting.

Many advertisers use posttests to assess the overall impact of a completed campaign. If a company hoped to increase brand awareness from 20 percent to 50 percent and succeeded in increasing it to only 30 percent, then it is not spending enough, its ads are poor, or it has overlooked some other factor.

SALES-EFFECT RESEARCH What sales are generated by an ad that increases brand awareness by 20 percent and brand preference by 10 percent? The fewer or more controllable other factors such as features and price are, the easier it is to measure advertising’s effect on sales. The sales impact is easiest to measure in direct marketing situations and hardest in brand or corporate image-building advertising.

Companies want to know whether they are overspending or underspending on advertising. One way to answer this question is to work with the formulation shown in Figure 20.4. A company’s share of advertising expenditures produces a share of voice (proportion of company advertising of that product to all advertising of that product) that earns a share of consumers’ minds and hearts and, ultimately, a share of market.

Researchers can measure sales impact with the historical approach, which uses advanced statistical techniques to correlate past sales to past advertising expenditures.44 Other researchers use experimental data to measure advertising’s sales impact. A growing number of researchers measure the sales effect of advertising expenditures instead of settling for communication-effect measures.45 Millward Brown International has conducted tracking studies for years to help advertisers decide whether their advertising is benefiting their brand.46

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

he blog was how do i say it… relevant, finally something that helped me. Thanks