A lot or batch size is the quantity that a stage of a supply chain either produces or purchases at a time. Consider, for example, a computer store that sells an average of four printers a day. The store manager, however, orders 80 printers from the manufacturer each time he places an order. The lot or batch size in this case is 80 printers. Given daily sales of four printers, it takes an average of 20 days before the store sells the entire lot and purchases a replenishment lot. The computer store holds an inventory of printers because the manager purchases a lot size larger than the store’s daily sales. Cycle inventory is the average inventory in a supply chain due to either production or purchases in lot sizes that are larger than those demanded by the customer.

In the rest of this chapter, we use the following notation:

Q: Quantity in a lot or batch size

D: Demand per unit time

Here, we ignore the impact of demand variability and assume that demand is stable. In Chapter 12, we introduce demand variability and its impact on safety inventory.

Let us consider the cycle inventory of jeans at Jean-Mart, a department store. The demand for jeans is relatively stable at D = 100 pairs of jeans per day. The store manager at Jean-Mart currently purchases in lots of Q = 1,000 pairs. The inventory profile of jeans at Jean-Mart is a plot depicting the level of inventory over time, as shown in Figure 11-1.

Because purchases are in lots of Q = 1,000 units, whereas demand is only D = 100 units per day, it takes 10 days for an entire lot to be sold. Over these 10 days, the inventory of jeans at Jean-Mart declines steadily from 1,000 units (when the lot arrives) to 0 (when the last pair is sold). This sequence of a lot arriving and demand depleting inventory until another lot arrives repeats itself every 10 days, as shown in the inventory profile in Figure 11-1.

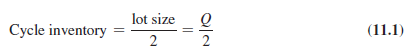

When demand is steady, cycle inventory and lot size are related as follows:

For a lot size of 1,000 units, Jean-Mart carries a cycle inventory of Q/2 = 500 pairs of jeans. From Equation 11.1, we see that cycle inventory is proportional to the lot size. A supply chain in which stages produce or purchase in larger lots has more cycle inventory than a supply chain in which stages produce and purchase in smaller lots. For example, if a competing department store with the same demand purchases in lot sizes of 200 pairs of jeans, it will carry a cycle inventory of only 100 pairs of jeans.

Lot sizes and cycle inventory also influence the flow time of material within the supply chain. Recall from Little’s Law (Equation 3.1) that

![]()

For any supply chain, average flow rate equals demand. We thus have

Average flow time resulting from cycle inventory

![]()

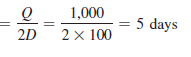

For lot sizes of 1,000 pairs of jeans and daily demand of 100 pairs of jeans, we obtain

Average flow time resulting from cycle inventory

Cycle inventory at the Jean-Mart store thus adds five days to the average amount of time that jeans spend in the supply chain. The larger the cycle inventory, the longer the lag time between when a product is produced and when it is sold. A lower level of cycle inventory is always desirable, because long time lags leave a firm vulnerable to demand changes in the marketplace. A lower cycle inventory also decreases a firm’s working capital requirement. Toyota, for example, keeps a cycle inventory of only a few hours of production between the factory and most suppliers. As a result, Toyota is never left with unneeded parts, and its working capital requirements are less than those of its competitors. Toyota also allocates very little space in the factory to inventory.

Zara and Seven-Eleven Japan are two companies that have built their strategy on the ability to replenish their stores in small lots. Seven-Eleven replenishes its stores in Japan with fresh food three times a day. The small replenishment batch allows Seven-Eleven to provide product that is is always very fresh. Zara replenishes its European stores up to three times a week. Each replenishment batch thus contains only about two days of demand. This ensures that Zara’s inventory on hand closely tracks customer demand. In both instances the firms have used small batch replenishment to ensure that their supply closely tracks customer demand trends.

Before we suggest actions that a manager can take to reduce cycle inventory, it is important to understand why stages of a supply chain produce or purchase in large lots and how lot size reduction affects supply chain performance.

Cycle inventory is held to take advantage of economies of scale and reduce cost within a supply chain. For example, apparel is shipped from Asia to North America in full container loads to reduce the transportation cost per unit. Similarly, an integrated steel mill produces hundreds of tons of steel per lot to spread that high cost of setup over a large batch. To understand how the supply chain achieves these economies of scale, we first identify supply chain costs that are influenced by lot size.

The average price paid per unit purchased is a key cost in the lot-sizing decision. A buyer may increase the lot size if this action results in a reduction in the price paid per unit purchased. For example, if the jeans manufacturer charges $20 per pair for orders under 500 pairs of jeans and $18 per pair for larger orders, the store manager at Jean-Mart gets the lower price by ordering in lots of at least 500 pairs of jeans. The price paid per unit is referred to as the material cost and is denoted by C. It is measured in dollars per unit. In many practical situations, material cost displays economies of scale—increasing lot size decreases material cost.

The fixed ordering cost includes all costs that do not vary with the size of the order but are incurred each time an order is placed. There may be a fixed administrative cost to place an order, a fixed trucking cost to transport the order, and a fixed labor cost to receive the order. Jean-Mart incurs a cost of $400 for the truck regardless of the number of pairs of jeans shipped. If the truck can hold up to 2,000 pairs of jeans, a lot size of 100 pairs results in a transportation cost of $4/pair, whereas a lot size of 1,000 pairs results in a transportation cost of $0.40/pair. Given the fixed transportation cost per batch, the store manager can reduce transportation cost per unit by increasing the lot size. The fixed ordering cost per lot or batch is denoted by S (commonly thought of as a setup cost) and is measured in dollars per lot. The ordering cost also displays economies of scale—increasing the lot size decreases the fixed ordering cost per unit purchased.

Holding cost is the cost of carrying one unit in inventory for a specified period of time, usually one year. It is a combination of the cost of capital, the cost of physically storing the inventory, and the cost that results from the product becoming obsolete. The holding cost is denoted by H and is measured in dollars per unit per year. It may also be obtained as a fraction, h, of the unit cost of the product. Given a unit cost of C, the holding cost H is given by

H = hC (11.2)

The total holding cost increases with an increase in lot size and cycle inventory.

To summarize, the following costs must be considered in any lot-sizing decision:

- Average price per unit purchased, $C/unit

- Fixed ordering cost incurred per lot, $S/lot

- Holding cost incurred per unit per year, $H/unit/year = hC

Later in the chapter, we discuss how the various costs may be estimated in practice. However, for the purposes of this discussion, we assume they are already known.

The primary role of cycle inventory is to allow different stages in a supply chain to purchase product in lot sizes that minimize the sum of the material, ordering, and holding costs. If a manager considers the holding cost alone, he or she will reduce the lot size and cycle inventory. Economies of scale in purchasing and ordering, however, motivate a manager to increase the lot size and cycle inventory. A manager must make the trade-off that minimizes total cost when making lot-sizing decisions.

Ideally, cycle inventory decisions should be made considering the total cost across the entire supply chain. In practice, however, it is generally the case that each stage makes its cycle inventory decisions independently. As we discuss later in the chapter, this practice increases the level of cycle inventory as well as the total cost in the supply chain.

Any stage of the supply chain exploits economies of scale in its replenishment decisions in the following three typical situations:

- A fixed cost is incurred each time an order is placed or produced.

- The supplier offers price discounts based on the quantity purchased per lot.

- The supplier offers short-term price discounts or holds trade promotions.

In the following sections, we review how purchasing managers can best respond to these situations.

Source: Chopra Sunil, Meindl Peter (2014), Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, Pearson; 6th edition.

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

14 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021