The premise of this book and this chapter is that systems to support decision making produce better decision making by managers and employees, aboveaverage returns on investment for the firm, and ultimately higher profitability. However, information systems cannot improve every decision taking place in an organization. Let’s examine the role of managers and decision making in organizations to see why this is so.

1. Managerial Roles

Managers play key roles in organizations. Their responsibilities range from making decisions, to writing reports, to attending meetings, to arranging birthday parties. We are able to better understand managerial functions and roles by examining classical and contemporary models of managerial behavior.

The classical model of management, which describes what managers do, was largely unquestioned for more than 70 years after the 1920s. Henri Fayol and other early writers first described the five classical functions of managers as planning, organizing, coordinating, deciding, and controlling. This description of management activities dominated management thought for a long time, and it is still popular today.

The classical model describes formal managerial functions but does not address exactly what managers do when they plan, decide things, and control the work of others. For this, we must turn to the work of contemporary behavioral scientists who have studied managers in daily action. Behavioral models argue that the actual behavior of managers appears to be less systematic, more informal, less reflective, more reactive, and less well organized than the classical model would have us believe.

Observers find that managerial behavior actually has five attributes that differ greatly from the classical description. First, managers perform a great deal of work at an unrelenting pace — studies have found that managers engage in more than 600 different activities each day, with no break in their pace. There is never enough time to do everything for which a CEO is responsible (Porter and Nohria, 2018). Second, managerial activities are fragmented; most activities last for less than nine minutes, and only 10 percent of the activities exceed one hour in duration. Third, managers prefer current, specific, and ad hoc information (printed information often will be too old). Fourth, they prefer oral forms of communication to written forms because oral media provide greater flexibility, require less effort, and bring a faster response. Fifth, managers give high priority to maintaining a diverse and complex web of contacts that acts as an informal information system and helps them execute their personal agendas and short- and long-term goals.

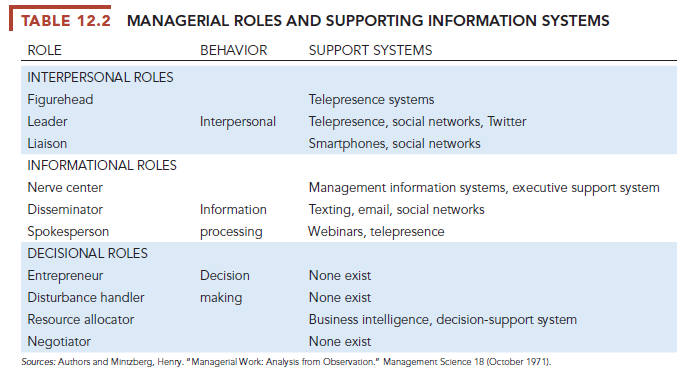

Analyzing managers’ day-to-day behavior, Henry Mintzberg found that it could be classified into 10 managerial roles (Mintzberg, 1971). Managerial roles are expectations of the activities that managers should perform in an organization. Mintzberg found that these managerial roles fell into three categories: interpersonal, informational, and decisional.

1.1. Interpersonal Roles

Managers act as figureheads for the organization when they represent their companies to the outside world and perform symbolic duties, such as giving out employee awards, in their interpersonal role. Managers act as leaders, attempting to motivate, counsel, and support subordinates. Managers also act as liaisons between various organizational levels; within each of these levels, they serve as liaisons among the members of the management team. Managers provide time and favors, which they expect to be returned.

1.2. Informational Roles

In their informational role, managers act as the nerve centers of their organizations, receiving the most concrete, up-to-date information and redistributing it to those who need to be aware of it. Managers are therefore information disseminators and spokespersons for their organizations.

1.3. Decisional Roles

Managers make decisions. In their decisional role, they act as entrepreneurs by initiating new kinds of activities, they handle disturbances arising in the organization, they allocate resources to staff members who need them, and they negotiate conflicts and mediate between conflicting groups.

Table 12.2, based on Mintzberg’s role classifications, is one look at where systems can and cannot help managers. The table shows that information systems are now capable of supporting most, but not all, areas of managerial life.

2. Real-World Decision Making

We now see that information systems are not helpful for all managerial roles. And in those managerial roles where information systems might improve decisions, investments in information technology do not always produce positive results. There are three main reasons: information quality, management filters, and organizational culture (see Chapter 3).

2.1. Information Quality

High-quality decisions require high-quality information. Table 12.3 describes information quality dimensions that affect the quality of decisions.

If the output of information systems does not meet these quality criteria, decision making will suffer. Chapter 6 describes how corporate databases and files have varying levels of inaccuracy and incompleteness, which in turn will degrade the quality of decision making.

2.2. Management Filters

Even with timely, accurate information, managers often make bad decisions. Managers (like all human beings) absorb information through a series of filters to make sense of the world around them. Cognitive scientists, behavioral economists, and recently neuro-economists have found that managers, like other humans, are poor at assessing risk, and are risk averse; perceive patterns where none exist; and make decisions based on intuition, feelings, and the framing of the problem as opposed to empirical data (Kahneman, 2011; Tversky and Kahneman, 1986).

For instance, Wall Street firms such as Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers imploded in 2008 because they underestimated the risk of their investments in complex mortgage securities, many of which were based on subprime loans that were more likely to default. The computer models they and other financial institutions used to manage risk were based on overly optimistic assumptions and overly simplistic data about what might go wrong. Management wanted to make sure that their firms’ capital was not all tied up as a cushion against defaults from risky investments, preventing them from investing it to generate profits. So the designers of these risk management systems were encouraged to measure risks in a way that minimized their risk.

2.3. Organizational Inertia and Politics

Organizations are bureaucracies with limited capabilities and competencies for acting decisively. When environments change and businesses need to adopt new business models to survive, strong forces within organizations resist making decisions calling for major change. Decisions taken by a firm often represent a balancing of the firm’s various interest groups rather than the best solution to the problem.

Studies of business restructuring find that firms tend to ignore poor performance until threatened by outside takeovers, and they systematically blame poor performance on external forces beyond their control-such as economic conditions (the economy), foreign competition, and rising prices-rather than blaming senior or middle management for poor business judgment. When the external business environment is positive and firm performance improves, managers typically credit themselves for the improved performance rather than the positive environment.

3. High-Velocity Automated Decision Making

Today, many decisions made by organizations are not made by managers-or any humans. For instance, when you enter a query into Google’s search engine, Google has to decide which URLs to display in about half a second on average (500 milliseconds). High-frequency traders at electronic stock exchanges execute their trades in under 30 milliseconds.

In high-velocity decision environments, the intelligence, design, choice, and implementation parts of the decision-making process are captured by the software’s algorithms. The humans who wrote the software have already identified the problem, designed a method for finding a solution, defined a range of acceptable solutions, and implemented a solution. Obviously, with humans out of the loop, great care needs to be taken to ensure the proper operation of these systems to prevent significant harm.

Organizations in these areas are making decisions faster than what managers can monitor or control. The past few years have seen a series of breakdowns in computerized trading systems, including one on August 1, 2012, when a software error caused Knight Capital to enter millions of faulty trades in less than an hour. The trading glitch created wild surges and plunges in nearly 150 stocks and left Knight with $440 million in losses.

Source: Laudon Kenneth C., Laudon Jane Price (2020), Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, Pearson; 16th edition.

I used to be recommended this website through my cousin. I’m no longer sure whether or not this post is written by means of him as no one else know such designated approximately my difficulty. You are wonderful! Thanks!

whoah this blog is great i love reading your articles. Keep up the great work! You know, many people are looking around for this info, you can aid them greatly.