In this section, we discuss distribution network choices from the manufacturer to the end consumer. When considering distribution between any other pair of stages, such as supplier to manufacturer or even a service company serving its customers through a distribution network, many of the same options still apply. Managers must make two key decisions when designing a distribution network:

- Will product be delivered to the customer location or picked up from a prearranged site?

- Will product flow through an intermediary (or intermediate location)?

Based on the firm’s industry and the answers to these two questions, one of six distinct distribution network designs may be used to move products from factory to customer. These designs are classified as follows:

- Manufacturer storage with direct shipping

- Manufacturer storage with direct shipping and in-transit merge

- Distributor storage with carrier delivery

- Distributor storage with last-mile delivery

- Manufacturer/distributor storage with customer pickup

- Retail storage with customer pickup

1. Manufacturer storage with Direct shipping

In this option, product is shipped directly from the manufacturer to the end customer, bypassing the retailer (who takes the order and initiates the delivery request). This option is also referred to as drop-shipping. The retailer carries no inventory. Information flows from the customer, via the retailer, to the manufacturer, and product is shipped directly from the manufacturer to customers, as shown in Figure 4-6. Online retailers such as eBags and Nordstrom.com use drop-shipping to deliver goods to the end consumer. eBags holds few bags in inventory. Nordstrom carries some products in inventory and uses the drop-ship model for slow-moving footwear. W.W. Grainger also uses drop-shipping to deliver slow-moving items to customers.

The biggest advantage of drop-shipping is the ability to centralize inventories at the manufacturer, which can aggregate demand across all retailers that it supplies. As a result, the supply chain is able to provide a high level of product availability with lower levels of inventory. A key issue with regard to drop-shipping is the ownership structure of the inventory at the manufacturer. If specified portions of inventory at the manufacturer are allocated to individual retailers, there is little benefit of aggregation even though the inventory is physically aggregated. Benefit of aggregation is achieved only if the manufacturer can allocate at least a portion of the available inventory across retailers on an as-needed basis. The benefits from centralization are highest for high-value, low-demand items with unpredictable demand. The decision of Nordstrom to drop- ship low-demand shoes satisfies these criteria. Similarly, bags sold by eBags tend to have high value and relatively low demand per SKU. The inventory benefits of aggregation are small for items with predictable demand and low value. Thus, drop-shipping does not offer a significant inventory advantage to an online grocer selling a staple item such as detergent. For slow-moving items, inventory turns can increase by a factor of six or higher if drop-shipping is used instead of storage at retail stores.

Drop-shipping also offers the manufacturer the opportunity to postpone customization until after a customer has placed an order. Postponement, if implemented, further lowers inventories by aggregating to the component level. For example, a publisher may drop-ship books that have been printed on demand, thus reducing the value of inventory held.

Although inventory costs are typically low with drop-shipping, transportation costs are high because manufacturers are farther from the end consumer. With drop-shipping, a customer order including items from several manufacturers will involve multiple shipments to the customer. This loss in aggregation of outbound transportation also increases cost.

Supply chains save on the fixed cost of facilities when using drop-shipping because all inventories are centralized at the manufacturer. This eliminates the need for other warehousing space in the supply chain. There can be some savings of handling costs as well, because the transfer from manufacturer to retailer no longer occurs. Handling cost savings must be evaluated carefully, however, because the manufacturer is now required to transfer items to the factory warehouse in full cases and then ship out from the warehouse in single units. The inability of a manufacturer to develop single-unit delivery capabilities can have a significant negative effect on handling cost and response time. Handling costs can be reduced significantly if the manufacturer has the capability to ship orders directly from the production line.

A good information infrastructure is needed between the retailers and the manufacturer so the retailer can provide product availability information to the customer, even though the inventory is located at the manufacturer. The customer should also have visibility into order processing at the manufacturer, even with the order being placed with the retailer. Drop-shipping generally requires significant investment in information infrastructure.

Response times tend to be long when drop-shipping is used because the order must be transmitted from the retailer to the manufacturer and shipping distances are generally longer from the manufacturer’s centralized site. eBags, for example, states that order processing may take from 1 to 5 days and ground transportation after that may take from 3 to 11 business days. This implies that customer response time at eBags will be 4 to 16 days using ground transportation and drop-shipping.

Another issue is that the response time need not be identical for every manufacturer that is part of a customer order. Given an order containing products from several sources, the customer will receive multiple partial shipments over time, making receiving more complicated for the customer.

Manufacturer storage allows a high level of product variety to be available to the customer. With a drop-shipping model, every product at the manufacturer can be made available to the customer without any limits imposed by shelf space. W.W. Grainger is able to offer hundreds of thousands of slow-moving items from thousands of manufacturers using drop-shipping. This would be impossible if each product had to be stored by W.W. Grainger. Drop-shipping allows a new product to be available to the market on the day the first unit is produced.

Drop-shipping provides a good customer experience in the form of delivery to the customer location. The experience, however, suffers when a single order containing products from several manufacturers is delivered in partial shipments.

Order visibility is important in the context of manufacturer storage, because two stages in the supply chain are involved in every customer order. Failure to provide this capability is likely to have a significant negative effect on customer satisfaction. Order tracking, however, becomes harder to implement in a drop-ship system because it requires complete integration of information systems at both the retailer and the manufacturer.

A manufacturer storage network is likely to have difficulty handling returns, hurting customer satisfaction. The handling of returns is more expensive under drop-shipping because each order may involve shipments from more than one manufacturer. Returns can be handled in two ways. One is for the customer to return the product directly to the manufacturer. The second approach is for the retailer to set up a separate facility (across all manufacturers) to handle returns. The first approach incurs high transportation and coordination costs, whereas the second approach requires investment in a facility to handle returns.

The performance characteristics of drop-shipping along various dimensions are summarized in Table 4-1.

Given its performance characteristics, manufacturer storage with direct shipping is best suited for a large variety of low-demand, high-value items for which customers are willing to wait for delivery and accept several partial shipments. Manufacturer storage is also suitable if it allows the manufacturer to postpone customization, thus reducing inventories. It is thus ideal for direct sellers that are able to build to order. For drop-shipping to be effective, there should be few sourcing locations per order.

2. Manufacturer Storage with Direct Shipping and in-Transit Merge

Unlike pure drop-shipping, under which each product in the order is sent directly from its manufacturer to the end customer, in-transit merge combines pieces of the order coming from different locations so the customer gets a single delivery. Information and product flows for the in-transit merge network are shown in Figure 4-7. In-transit merge has been used by Dell and can be used by companies implementing drop-shipping. When a customer ordered a PC from Dell along with a Sony monitor (during Dell’s direct selling period), the package carrier picked up the PC from the Dell factory and the monitor from the Sony factory; it then merged the two at a hub before making a single delivery to the customer.

As with drop-shipping, the ability to aggregate inventories and postpone product customization is a significant advantage of in-transit merge. In-transit merge allowed Dell and Sony to hold all their inventories at the factory. This approach has the greatest benefits for products with high value whose demand is difficult to forecast, particularly if product customization can be postponed.

Although an increase in coordination is required, in-transit merge decreases transportation costs relative to drop-shipping by aggregating the final delivery.

Facility and processing costs for the manufacturer and the retailer are similar to those for drop-shipping. The party performing the in-transit merge has higher facility costs because of the merge capability required. Receiving costs at the customer are lower because a single delivery is received. Overall supply chain facility and handling costs are somewhat higher than with drop-shipping.

A sophisticated information infrastructure is needed to allow in-transit merge. In addition to information, operations at the retailer, manufacturers, and the carrier must be coordinated. The investment in information infrastructure is higher than that for drop-shipping.

Response times, product variety, availability, and time to market are similar to those for drop-shipping. Response times may be higher if the shipments from the various sources are not coordinated. Customer experience is likely to be better than with drop-shipping, because the customer receives only one delivery for an order instead of many partial shipments. Order visibility is an important requirement. Although the initial setup is difficult because it requires integration of manufacturer, carrier, and retailer, tracking itself becomes easier given the merge that occurs at the carrier hub.

Returnability is similar to that with drop-shipping. As with drop-shipping, problems in handling returns are likely, and the reverse supply chain will continue to be expensive and difficult to implement.

The performance of factory storage with in-transit merge is compared with that of dropshipping in Table 4-2. The main advantages of in-transit merge over drop-shipping are lower transportation cost and improved customer experience. The major disadvantage is the additional effort during the merge itself. Given its performance characteristics, manufacturer storage with in-transit merge is best suited for low- to medium-demand, high-value items the retailer is sourcing from a limited number of manufacturers. Compared with drop-shipping, in-transit merge requires a higher demand from each manufacturer (not necessarily each product) to be effective. When there are too many sources, in-transit merge can be difficult to coordinate and implement. In-transit merge is best implemented if there are no more than four or five sourcing locations. The in-transit merge of a Dell PC with a Sony monitor was appropriate because product variety was high, but there were few sourcing locations with relatively large total demand from each sourcing location.

3. Distributor Storage with Carrier Delivery

Under this option, inventory is held not by manufacturers at the factories, but by distributors/ retailers in intermediate warehouses, and package carriers are used to transport products from the intermediate location to the final customer. Amazon and industrial distributors such as W.W. Grainger and McMaster-Carr have used this approach combined with drop-shipping from a manufacturer (or distributor). Information and product flows when using distributor storage with delivery by a package carrier are shown in Figure 4-8.

Relative to manufacturer storage, distributor storage requires a higher level of inventory because of a loss of aggregation. From an inventory perspective, distributor storage makes sense for products with somewhat higher demand. This is seen in the operations of both Amazon and W.W. Grainger. They stock only the slow- to fast-moving items at their warehouses, with very- slow-moving items stocked farther upstream. In some instances, postponement of product differentiation can be implemented with distributor storage, but it does require that the warehouse develop some assembly capability. Distributor storage, however, requires much less inventory than a retail network. In 2013, Amazon used warehouse storage to turn its inventory about twice as fast as the retail network of Barnes & Noble.

Transportation costs are somewhat lower for distributor storage compared with those for manufacturer storage because an economic mode of transportation (e.g., truckloads) can be employed for inbound shipments to the warehouse, which is closer to the customer. Unlike manufacturer storage, under which multiple shipments may need to go out for a single customer order with multiple items, distributor storage allows outbound orders to the customer to be bundled into a single shipment, further reducing transportation cost. Distributor storage provides savings on the transportation of faster-moving items relative to manufacturer storage.

Compared with those for manufacturer storage, facility costs (of warehousing) are somewhat higher with distributor storage because of a loss of aggregation. Processing and handling costs are comparable to those of manufacturer storage unless the factory is able to ship to the end customer directly from the production line. In that case, distributor storage has higher processing costs. From a facility cost perspective, distributor storage is not appropriate for extremely slow- moving items.

The information infrastructure needed with distributor storage is significantly less complex than that needed with manufacturer storage. The distributor warehouse serves as a buffer between the customer and the manufacturer, decreasing the need to coordinate the two completely. Real-time visibility between customers and the warehouse is needed, whereas real-time visibility between the customer and the manufacturer is not. Visibility between the distributor warehouse and manufacturer can be achieved at a much lower cost than real-time visibility between the customer and manufacturer.

Response time under distributor storage is better than under manufacturer storage because distributor warehouses are, on average, closer to customers, and the entire order is aggregated at the warehouse before being shipped. Amazon, for example, processes most warehouse-stored items within a day and then it takes three to five business days using ground transportation for the order to reach the customer. W.W. Grainger processes customer orders on the same day and has enough warehouses to deliver most orders the next day using ground transport. Warehouse storage limits to some extent the variety of products that can be offered. W.W. Grainger does not store very-low-demand items at its warehouse, relying on manufacturers to drop-ship those products to the customer. Customer convenience is high with distributor storage because a single shipment reaches the customer in response to an order. Time to market under distributor storage is somewhat higher than that under manufacturer storage because of the need to stock another stage in the supply chain. Order visibility becomes easier than with manufacturer storage because there is a single shipment from the warehouse to the customer and only one stage of the supply chain is directly involved in filling the customer order. Returnability is better than it is with manufacturer storage because all returns can be processed at the warehouse itself. The customer also has to return only one package, even if the items are from several manufacturers.

The performance of distributor storage with carrier delivery is summarized in Table 4-3. Distributor storage with carrier delivery is well suited for slow- to fast-moving items. Distributor storage also makes sense when customers want delivery faster than is offered by manufacturer storage but do not need delivery immediately. Distributor storage can handle somewhat lower variety than manufacturer storage but can handle a much higher level of variety than a chain of retail stores.

4. Distributor Storage with Last-Mile Delivery

Last-mile delivery refers to the distributor/retailer delivering the product to the customer’s home instead of using a package carrier. AmazonFresh, Peapod, and Tesco have used last-mile delivery in the grocery industry. Companies such as Kozmo and Urbanfetch tried to set up home-delivery networks for a variety of products, but they failed to survive. The automotive spare parts industry is one in which distributor storage with last-mile delivery is the dominant model. It is too expensive for dealers to carry all spare parts in inventory. Thus, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) tend to carry most spare parts at a local distribution center typically located no more than a couple of hours’ drive from their dealers and often managed by a third party. The local distribution center is responsible for delivering needed parts to a set of dealers and makes multiple deliveries per day. Unlike package carrier delivery, last-mile delivery requires the distributor warehouse to be much closer to the customer. Given the limited radius that can be served with last-mile delivery, more warehouses are required compared to when package delivery is used. The warehouse storage with last-mile delivery network is as shown in Figure 4-9.

Distributor storage with last-mile delivery requires higher levels of inventory than the other options (except for retail stores) because it has a lower level of aggregation. From an inventory perspective, warehouse storage with last-mile delivery is suitable for relatively fast-moving items that are needed quickly and for which some level of aggregation is beneficial. Auto parts required by car dealers fit this description.

Among all the distribution networks, transportation costs are highest for last-mile delivery, especially when delivering to individuals. This is because package carriers aggregate delivery across many retailers and are able to obtain better economies of scale than are available to a distributor/retailer attempting last-mile delivery. Delivery costs (including transportation and processing) can be more than $20 per home delivery in the grocery industry. Last-mile delivery may be somewhat less expensive in large, dense cities, especially if the distributor has very large sales and carries a wide range of products. Amazon, with high sales across a wide variety of product categories, seems better equipped for last-mile delivery than Peapod, which carries only grocery items. A third party serving a wide variety of retailers may also be able to provide last- mile delivery effectively, given its ability to amortize its distribution costs across a large stream of deliveries. Transportation costs may also be justifiable for bulky products for which the customer is willing to pay for home delivery. Home delivery of water and large bags of rice has proved quite successful in China, where the high population density has helped decrease delivery costs. Transportation costs of last-mile delivery are best justified in settings where the customer is purchasing in large quantities. This is rare for individual customers, but businesses such as auto dealerships purchase large quantities of spare parts on a daily basis and can thus justify daily delivery. Home delivery to individual customers can be justified for bulky items such as five-gallon jugs of water in the United States and large bags of rice in China. In each instance, last-mile delivery is cheaper and more convenient than customers picking up their own bottles or bags.

Using this option, facility costs are somewhat lower than those for a network with retail stores but much higher than for either manufacturer storage or distributor storage with package carrier delivery. Processing costs, however, are much higher than those for a network of retail stores because all customer participation is eliminated. A grocery store using last-mile delivery performs all the processing until the product is delivered to the customer’s home, unlike a supermarket, where the customer does much more work.

The information infrastructure with last-mile delivery is similar to that for distributor storage with package carrier delivery. However, it requires the additional capability of scheduling deliveries.

Response times for last-mile delivery are faster than those for package carriers. Kozmo and Urbanfetch tried to provide same-day delivery, whereas online grocers typically provide next- day delivery. Product variety is generally lower than for distributor storage with carrier delivery. The cost of providing product availability is higher than for every option other than retail stores. The customer experience can be good using this option, particularly for bulky, hard-to-carry items. Time to market is even higher than for distributor storage with package carrier delivery because the new product has to penetrate deeper before it is available to the customer. Order visibility is less of an issue, given that deliveries are made within 24 hours. The order-tracking feature does become important to handle exceptions in case of incomplete or undelivered orders. Of all the options discussed, returnability is best with last-mile delivery, because trucks making deliveries can also pick up returns from customers. Returns are still more expensive to handle in this manner than at a retail store, where a customer can bring the product back.

The performance characteristics of distributor storage with last-mile delivery are summarized in Table 4-4. In areas with high labor costs, it is hard to justify last-mile delivery to individual consumers on the basis of efficiency or improved margin. Last-mile delivery may be justifiable if customer orders are large enough to provide some economies of scale and customers are willing to pay for this convenience. Peapod has changed its pricing policies to reflect this idea. Its minimum order size is $60 (with a delivery charge of $9.95), and delivery charges drop to $6.95 for orders totaling more than $100. Peapod offers discounts for deliveries during slower periods based on what its schedule looks like. Last-mile delivery is easier to justify when the customer is a business like an auto dealer purchasing large quantities.

5. Manufacturer or Distributor Storage with Customer Pickup

In this approach, inventory is stored at the manufacturer or distributor warehouse, but customers place their orders online or on the phone and then travel to designated pickup points to collect their merchandise. Orders are shipped from the storage site to the pickup points as needed. Examples include 7dream.com and Otoriyose-bin, operated by Seven-Eleven Japan, which allow customers to pick up online orders at a designated store. Tesco has implemented such a service in the United Kingdom, where customers can pick up orders they have placed online. Amazon is also experimenting with Amazon lockers, where customers can pick up their shipments. A business-to- business (B2B) example is W.W. Grainger, whose customers can pick up their orders at one of the W.W. Grainger retail outlets. Some items are stored at the pickup location, whereas others may come from a central location. In the case of 7dream.com, the order is delivered from a manufacturer or distributor warehouse to the pickup location. In 2007, Walmart launched its “Site to Store” service, which allows customers to order thousands of products online at Walmart.com and have them shipped free to a local Walmart store. Items arrive in stores 7 to 10 business days after the order is processed, and customers receive an e-mail notification when their order is ready for pickup.

The information and product flows shown in Figure 4-10 are similar to those in the Seven- Eleven Japan network. Seven-Eleven has distribution centers where product from manufacturers is cross-docked and sent to retail outlets on a daily basis. An online retailer delivering an order through Seven-Eleven can be treated as one of the manufacturers, with deliveries cross-docked and sent to the appropriate Seven-Eleven outlet. Serving as an outlet for online orders allows Seven-Eleven to improve utilization of its existing logistical assets.

Inventory costs using this approach can be kept low, with either manufacturer or distributor storage to exploit aggregation. W.W. Grainger keeps its inventory of fast-moving items at pickup locations, whereas slow-moving items are stocked at a central warehouse or in some cases at the manufacturer.

Transportation cost is lower than for any solution using package carriers because significant aggregation is possible when delivering orders to a pickup site. This allows the use of truckload or less-than-truckload carriers to transport orders to the pickup site. For a company such as Seven-Eleven Japan or Walmart, the marginal increase in transportation cost is small because trucks are already making deliveries to the stores, and their utilization can be improved by including online orders. As a result, Seven-Eleven Japan and Walmart allow customers to pick up orders without a shipping fee.

Facility costs are high if new pickup sites have to be built. A solution using existing sites can lower the additional facility costs. This, for example, is the case with 7dream.com, Walmart, and W.W. Grainger, for which the stores already exist. Processing costs at the manufacturer or the warehouse are comparable to those of other solutions. Processing costs at the pickup site are high because each order must be matched with a specific customer when he or she arrives. Creating this capability can increase processing costs significantly if appropriate storage and information systems are not provided. Increased processing cost and potential errors at the pickup site are the biggest hurdle to the success of this approach.

A significant information infrastructure is needed to provide visibility of the order until the customer picks it up. Good coordination is needed among the retailer, the storage location, and the pickup location.

In this case, a response time comparable to that using package carriers can be achieved. Variety and availability comparable to any manufacturer or distributor storage option can be provided. There is some loss of customer experience, because unlike the other options discussed, customers must pick up their own orders. On the other hand, customers who do not want to pay online can pay by cash using this option. In countries like Japan, where Seven-Eleven has more than 15,000 outlets, it can be argued that the loss of customer convenience is small, because most customers are close to a pickup site and can collect an order at their convenience. In some cases, this option is considered more convenient because it does not require the customer to be at home at the time of delivery. Time to market for new products can be as short as with manufacturer storage.

Order visibility is extremely important for customer pickups. The customer must be informed when the order has arrived, and the order should be easily identified once the customer arrives to pick it up. Such a system is hard to implement because it requires integration of several stages in the supply chain. Returns can potentially be handled at the pickup site, making it easier for customers. From a transportation perspective, return flows can be handled using the delivery trucks.

The performance characteristics of manufacturer or distributor storage with consumer pickup sites are summarized in Table 4-5. The main advantages of a network with consumer pickup sites are that it can lower the delivery cost and expand the set of products sold and customers served online. The major hurdle is the increased handling cost and complexity at the pickup site. Such a network is likely to be most effective if existing retail locations are used as pickup sites, because this type of network improves the economies from existing infrastructure. In particular, such a network can be effective for firms like Seven-Eleven Japan, Walmart, and W.W. Grainger, which have both a network of stores and an online business. Unfortunately, such retail sites are typically designed to allow the customer to do the picking and need to develop the capability of picking a customer-specific order.

6. Retail Storage with Customer Pickup

In this option, often viewed as the most traditional type of supply chain, inventory is stored locally at retail stores. Customers walk into the retail store or place an order online or by phone and pick it up at the retail store. Examples of companies that offer multiple options of order placement include Walmart and Tesco. In either case, customers can walk into the store or order online. A B2B example is W.W. Grainger: Customers can order online, by phone, or in person and pick up their order at one of W.W. Grainger’s retail outlets.

Local storage increases inventory costs because of the lack of aggregation. For fast- to very- fast-moving items, however, there is marginal increase in inventory, even with local storage. Walmart uses local storage for its fast-moving products while delivering a wider variety of products from its central location for pickup at the store. Similarly, W.W. Grainger keeps its inventory of fast-moving items at pickup locations, whereas slow-moving items are stocked at a central warehouse.

Transportation cost is much lower than with other solutions because inexpensive modes of transport can be used to replenish product at the retail store. Facility costs are high because many local facilities are required. A minimal information infrastructure is needed if customers walk into the store and place orders. For online orders, however, a significant information infrastructure is needed to provide visibility of the order until the customer picks it up.

Good response times can be achieved with this system because of local storage. For example, both Tesco and W.W. Grainger offer same-day pickup from their retail locations. Product variety stored locally is lower than that under other options. It is more expensive than with all other options to provide a high level of product availability. Customer experience depends on whether or not the customer likes to shop. Time to market is the highest with this option because the new product must penetrate through the entire supply chain before it is available to customers. Order visibility is extremely important for customer pickups when orders are placed online or by phone. Returns can be handled at the pickup site. Overall, returnability is fairly good using this option.

The performance characteristics of a network with customer pickup sites and local retail storage are summarized in Table 4-6. The main advantage of a network with retail storage is that it can lower delivery costs and provide a faster response than other networks. The major disadvantage is the increased inventory and facility costs. Such a network is best suited for fast-moving items or items for which customers value rapid response.

7. Selecting a Distribution Network Design

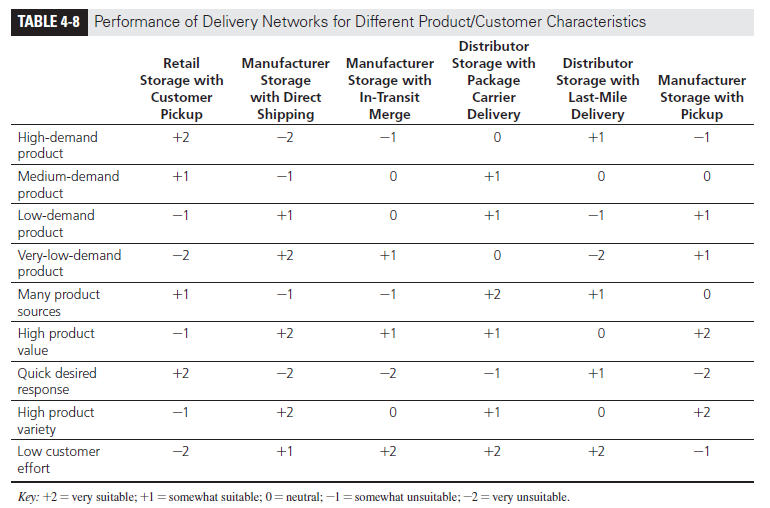

A network designer needs to consider product characteristics as well as network requirements when deciding on the appropriate delivery network. The various networks considered earlier have different strengths and weaknesses. In Table 4-7, the various delivery networks are ranked relative to one another along different performance dimensions. A ranking of 1 indicates the best performance along a given dimension; as the relative performance worsens, the ranking number increases.

Only niche companies end up using a single distribution network. Most companies are best served by a combination of delivery networks. The combination used depends on product characteristics and the strategic position that the firm is targeting. The suitability of different delivery designs (from a supply chain perspective) in various situations is shown in Table 4-8.

An excellent example of a hybrid network is that of W.W. Grainger, which combines all the aforementioned options in its distribution network. The network, however, is tailored to match the characteristics of the product and the needs of the customer. Fast-moving and emergency items are stocked locally, and customers can either pick them up or have them shipped, depending on the urgency. Slower-moving items are stocked at a national DC and shipped to the customer within a day or two. Very-slow-moving items are typically drop-shipped from the manufacturer and carry a longer lead time. Another hybrid network is used by Amazon, which stocks fast-moving items at most of its warehouses and slower-moving items at fewer warehouses; very-slow-moving items may be drop-shipped from suppliers.

We can now revisit the examples from the computer industry discussed at the beginning of the chapter. Gateway’s decision to create a network of retail stores without exploiting any of the supply chain advantages such a network offers was flawed. To fully exploit the benefits of the retail network, Gateway should have stocked its standard configurations (likely to have high demand) at the retail stores, with all other configurations drop-shipped from the factory (perhaps with local pickup at the retail stores if that was economical). Instead, it drop-shipped all configurations from the factory. Apple has opened several retail stores and actually carries products for sale at these stores. This makes sense, given the low variety and high demand for Apple products. In fact, Apple has seen consistent growth in sales and profits through its retail outlets.

Source: Chopra Sunil, Meindl Peter (2014), Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, Pearson; 6th edition.

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

14 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021

15 Jun 2021