A decision is a choice made from available alternatives. For example, an accounting man- ager’s selection among Colin, Tasha, and Carlos for the position of junior auditor is a decision. Many people assume that making a choice is the major part of decision making, but it is only a part.

Decision making is the process of identifying problems and opportunities and then resolving them. Decision making involves effort both before and after the actual choice. Thus, the decision as to whether to select Colin, Tasha, or Carlos requires the accounting manager to ascertain whether a new junior auditor is needed, determine the availability of potential job candidates, interview candidates to acquire necessary information, select one candidate, and follow up with the socialization of the new employee into the organization to ensure the decision’s success.

1. PROGRAMMED AND NONPROGRAMMED DECISIONS

Management decisions typically fall into one of two categories: programmed and nonpro- grammed. Programmed decisions involve situations that have occurred often enough to enable decision rules to be developed and applied in the future.4 Programmed decisions are made in response to recurring organizational problems. The decision to reorder paper and other office supplies when inventories drop to a certain level is a programmed decision. Other programmed decisions concern the types of skills required to fill certain jobs, the reorder point for manufacturing inventory, exception reporting for expenditures 10 percent or more over budget, and selection of freight routes for product deliveries. After managers formulate decision rules, subordinates and others can make the decision, freeing managers for other tasks.

Nonprogrammed decisions are made in response to situations that are unique, are poorly defined and largely unstructured, and have important consequences for the organiza- tion. Many nonprogrammed decisions involve strategic planning because uncertainty is great, and decisions are complex. Decisions to build a new factory, develop a new product or service, enter a new geographical market, or relocate headquarters to another city are all non- programmed decisions. One good example of a nonprogrammed decision is ExxonMobil’s decision to form a consortium to drill for oil in Siberia. One of the largest foreign invest- ments in Russia, the consortium committed $4.5 billion before pumping the first barrel and expects a total capital cost of $12+ billion. The venture could produce 250,000 barrels a day, about 10 percent of ExxonMobil’s global production. But if things go wrong, the oil giant, which has already invested some $4 billion, will take a crippling hit. At General Motors, top executives are facing multiple, enormously complex nonprogrammed decisions. The com- pany has been rapidly losing market share, and 2005 losses totaled $10.6 billion. The giant corporation is also subject to six Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) probes; is en- tangled in the impending bankruptcy of its largest supplier, Delphi; and is burdened by massive health care and unionized labor costs. Top GM executives have to analyze complex problems, evaluate alternatives, and make decisions about the best way to reverse GM’s sag- ging fortunes and keep the company out of bankruptcy.5

2. CERTAINTY, RISK, UNCERTAINTY, AND AMBIGUITY

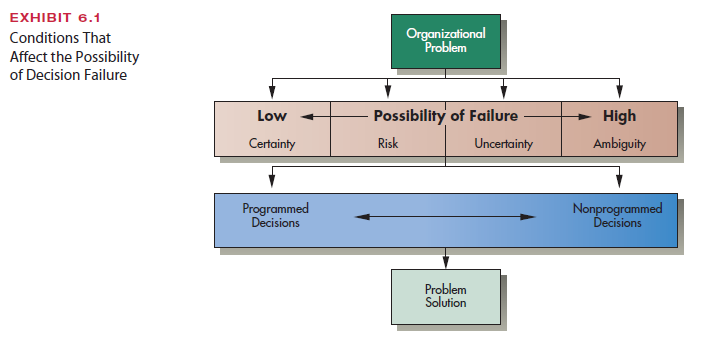

One primary difference between programmed and nonprogrammed decisions relates to the degree of certainty or uncertainty that managers deal with in making the decision. In a per- fect world, managers would have all the information necessary for making decisions. In re- ality, however, some things are unknowable; thus, some decisions will fail to solve the problem or attain the desired outcome. Managers try to obtain information about decision alternatives that will reduce decision uncertainty. Every decision situation can be organized on a scale according to the availability of information and the possibility of failure. The four positions on the scale are certainty, risk, uncertainty, and ambiguity, as illustrated in Exhibit 6.1. Whereas programmed decisions can be made in situations involving certainty, many situations that managers deal with every day involve at least some degree of uncer- tainty and require nonprogrammed decision making.

Certainty. Certainty means that all the information the decision maker needs is fully available.6 Managers have information on operating conditions, resource costs or constraints, and each course of action and possible outcome. For example, if a company considers a $10,000 investment in new equipment that it knows for certain will yield $4,000 in cost savings per year over the next five years, managers can calculate a before-tax rate of return of about 40 percent. If managers compare this investment with one that will yield only $3,000 per year in cost savings, they can confidently select the 40 percent return. However, few decisions are certain in the real world. Most contain risk or uncertainty.

Risk. Risk means that a decision has clear-cut goals and that good information is avail- able, but the future outcomes associated with each alternative are subject to chance. How- ever, enough information is available to allow the probability of a successful outcome for each alternative to be estimated.7 Statistical analysis might be used to calculate the proba- bilities of success or failure. The measure of risk captures the possibility that future events will render the alternative unsuccessful. For example, to make restaurant location decisions, McDonald’s can analyze potential customer demographics, traffic patterns, supply logistics, and the local competition, and come up with reasonably good forecasts of how successful a restaurant will be in each possible location.8

Uncertainty. Uncertainty means that managers know which goals they want to achieve, but information about alternatives and future events is incomplete. Managers do not have enough information to be clear about alternatives or to estimate their risk. Fac- tors that may affect a decision, such as price, production costs, volume, or future interest rates are difficult to analyze and predict. Managers may have to make assumptions from which to forge the decision even though it will be wrong if the assumptions are incorrect. Managers may have to come up with creative approaches to alternatives and use personal judgment to determine which alternative is best.

Managers at Wolters Kluwer, a leader in online information services based in The Netherlands, faced uncertainty as they considered ways to spark growth. The company had historically grown through acquisition, but that strategy had reached its limit. CEO Nancy McKinstry and other top managers talked with customers, analyzed the industry and Wolters Kluwer’s market position and capabilities, and decided to shift the company toward growing through internal development of new products and services. Wolters Kluwer didn’t have a track record in internal growth, and analysts were skeptical. Decisions about how to finance the internal development were complex and unclear, involving such considerations as staff reductions, restructuring of departments and divisions, and shifting operations to lower-cost facilities. Furthermore, decisions had to be made about which new and existing products to fund and at what levels.9 These decisions and others like them have no clear-cut solutions and require that managers rely on creativity, judgment, intu- ition, and experience to craft a response.

Many decisions made under uncertainty do not produce the desired results, but manag- ers face uncertainty every day. They find creative ways to cope with uncertainty to make more effective decisions.

Ambiguity. Ambiguity is by far the most difficult decision situation. Ambiguity means that the goals to be achieved or the problem to be solved is unclear, alternatives are difficult to define, and information about outcomes is unavailable.10 Ambiguity is what students would feel if an instructor created student groups, told each group to complete a project, but gave the groups no topic, direction, or guidelines whatsoever. Ambiguity has been called a wicked decision problem. Managers have a difficult time coming to grips with the issues. Wicked problems are associated with manager conflicts over goals and decision alternatives, rapidly changing circumstances, fuzzy information, and unclear linkages among decision ele- ments.11 Sometimes managers will come up with a “solution” only to realize that they hadn’t clearly defined the real problem to begin with.12 One example of a wicked decision problem was when managers at Ford Motor Company and Firestone confronted the problem of tires used on the Ford Explorer coming apart on the road, causing deadly blowouts and rollovers. Just defining the problem and whether the tire itself or the design of the Explorer was at fault was the first hurdle. Information was fuzzy and fast-changing, and managers were in conflict over how to handle the problem. Neither side dealt effectively with this decision situation, and the reputations of both companies suffered as a result. Fortunately, most decisions are not characterized by ambiguity. But when they are, managers must conjure up goals and develop reasonable scenarios for decision alternatives in the absence of information.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

6 May 2021

5 May 2021

5 May 2021

13 Dec 2018

6 May 2021

5 May 2021