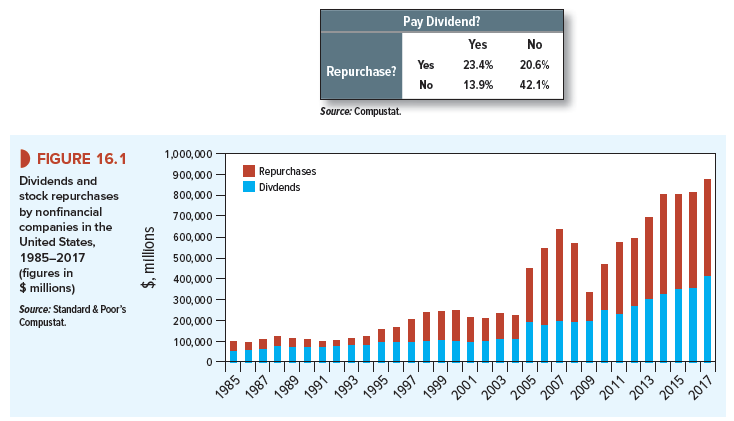

Corporations pay out cash by distributing dividends or by buying back some of their outstanding shares. Repurchases were rare in the early 1980s, but Figure 16.1 shows that the total value of repurchases in the United States is now similar to total dividends.

Figure 16.1 shows that dividends are more stable than repurchases. Notice how repurchases were cut back in the early 2000s and in the crisis of 2007-2009. Dividends also fell in the crisis, but by less than repurchases.

Cash-rich corporations sometimes undertake massive repurchase programs, but they often increase dividends at the same time. Here are four examples:

• Cisco Systems: A $25 billion repurchase program an a 14% increase in dividends.

• Mastercard: A $4 billion repurchase program and an increase in annual dividends from $.88 to $1.00 per share.

• Boeing: An $18 billion repurchase program and a 20% dividend increase to $1.71 per share.

• AbbVie, a pharmaceutical company: $10 billion repurchase program and a dividend increase from $.71 to $.96 per share.

The fraction of public industrial corporations that paid dividends was 57% in 1980. But the fraction decreased steadily in the 1980s and 1990s to about 16% at the turn of the century, then rebounded to about 42% in 2017. Repurchases in 1980 were tiny, but by 2017, about 48% of industrial companies repurchased. The fraction of banks that pay dividends has been much higher than for industrial companies, but the fraction of banks that repurchase has been about the same.1 Here is a table of payout practices, by nonfinancial firms, from 2011 to 2017:

On average in each year, 23.4% of the firms paid a dividend and also repurchased shares. The fraction that paid dividends but did not repurchase was 13.9%. The corresponding fraction for repurchases but no dividends was 20.6%. But 42.1% of firms did not pay dividends or repurchase shares.

Who are the nondividend payers? Some are companies that used to pay dividends, but then fell on hard times and had to cut back. However, most nondividend payers are growth companies that have never paid a dividend and will not pay one in the foreseeable future. The zero-dividend companies also include such household names as Berkshire Hathaway, Alphabet (Google), and Amazon.

1. How Firms Pay Dividends

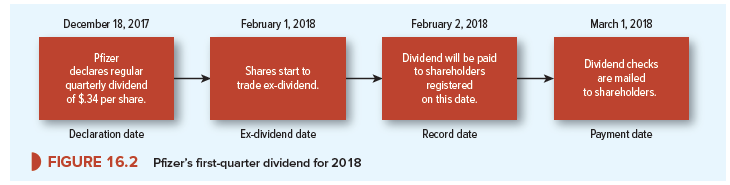

On December 18, 2017, Pfizer’s board of directors announced a quarterly cash dividend of $.34 per share. Who received this dividend? That may seem an obvious question, but shares trade constantly, and the firm’s records of who owns its shares are never fully up to date. So corporations specify a particular day’s roster of shareholders who qualify to receive each dividend. For example, Pfizer announced that it would send a dividend check on March 1, 2018 (the payment date), to all shareholders recorded in its books on February 2 (the record date).

One day before the record date, Pfizer stock began to trade ex-dividend. Investors who bought shares on or after that date did not have their purchases registered by the record date and were not entitled to the dividend. Other things equal, a stock is worth less if you miss out on the dividend. So when a stock “goes ex-dividend,” its price falls by about the amount of the dividend. Figure 16.2 illustrates the sequence of the key dividend dates. This sequence is the same whenever companies pay a dividend (though of course the actual dates will differ).

Corporations are not free to declare whatever dividend they choose. In some countries, such as Brazil and Chile, companies are obliged by law to pay out a minimum proportion of their earnings. Conversely, some restrictions may be imposed by lenders, who are concerned that excessive dividend payments would not leave enough in the kitty to repay their loans. In the United States, state law also helps to protect the firm’s creditors against excessive dividend payments. For example, companies are not allowed to pay a dividend out of legal capital, which is generally defined as the par value of outstanding shares.[1]

Most U.S. companies pay a regular cash dividend each quarter, but occasionally this is supplemented by a one-off extra or special dividend. Many companies offer shareholders automatic dividend reinvestment plans (DRIPs). Often, the new shares are issued at a 5% discount from the market price. Sometimes 10% or more of total dividends will be reinvested under such plans.

Dividends are not always in the form of cash. Companies also declare stock dividends. For example, if the firm pays a stock dividend of 5%, it sends each shareholder 5 extra shares for every 100 shares currently owned. A stock dividend is essentially the same as a stock split. Both increase the number of shares but do not affect the company’s assets, profits, or total value. So both reduce value per share.4 In this chapter, we focus on cash dividends.

2. How Firms Repurchase Stock

Instead of paying a dividend to its stockholders, the firm can use the cash to repurchase stock. The reacquired shares are kept in the company’s treasury and may be resold if the company needs money. There are four main ways to repurchase stock. By far the most common method is for the firm to announce that it plans to buy its stock in the open market, just like any other investor.5 However, companies sometimes use a tender offer where they offer to buy back a stated number of shares at a fixed price, which is typically set at about 20% above the current market level. Shareholders can then choose whether to accept this offer. A third procedure is to employ a Dutch auction. In this case, the firm states a series of prices at which it is prepared to repurchase stock. Shareholders submit offers declaring how many shares they wish to sell at each price and the company calculates the lowest price at which it can buy the desired number of shares. Finally, repurchase sometimes takes place by direct negotiation with a major shareholder.

In the past, many countries banned or severely restricted the use of stock repurchases. As a result, firms that had amassed large amounts of cash were tempted to invest it at low rates of return rather than hand it back to shareholders, who could have reinvested it in firms that were short of cash. But most of these limitations have now been removed, and many multinational giants now repurchase huge amounts of stock. For example, Royal Dutch Shell, Siemens, Toyota, and Novartis have all spent large sums on buying back their stock.

I always was concerned in this subject and stock still am, thankyou for putting up.

Some truly nice and useful info on this internet site, as well I think the pattern has good features.