Process theories explain how people select behavioral actions to meet their needs and determine whether their choices were successful. The two basic process theories are equity theory and expectancy theory.

1. EQUITY THEORY

Equity theory focuses on individuals’ perceptions of how fairly they are treated comp- ared with others. Developed by J. Stacy Adams, equity theory proposes that people are motivated to seek social equity in the rewards they expect for performance.21

According to equity theory, if people perceive their compensation as equal to what oth- ers receive for similar contributions, they will believe that their treatment is fair and equita- ble. People evaluate equity by a ratio of inputs to outcomes. Inputs to a job include education, experience, effort, and ability. Outcomes from a job include pay, recognition, benefits, and promotions. The input-to-outcome ratio may be compared to another person in the work group or to a perceived group average. A state of equity exists whenever the ratio of one person’s outcomes to inputs equals the ratio of another’s outcomes to inputs.

Inequity occurs when the input-to-outcome ratios are out of balance, such as when a person with a high level of education or experience receives the same salary as a new, less- educated employee. Interestingly, perceived inequity also occurs in the other direction. Thus, if an employee discovers she is making more money than other people who contrib- ute the same inputs to the company, she may feel the need to correct the inequity by work- ing harder, getting more education, or considering lower pay. Studies of the brain have shown that people get less satisfaction from money they receive without having to earn it than they do from money they work to receive.22 Perceived inequity creates tensions within individuals that motivate them to bring equity into balance.23

The most common methods for reducing a perceived inequity are these:

- Change inputs. A person may choose to increase or decrease his or her inputs to the orga- nization. For example, underpaid individuals may reduce their level of effort or increase their absenteeism. Overpaid people may increase their effort on the job.

- Change outcomes. A person may change his or her outcomes. An underpaid person may request a salary increase or a bigger office. A union may try to improve wages and work- ing conditions to be consistent with a comparable union whose members make more money.

- Distort perceptions. Research suggests that people may distort perceptions of equity if they are unable to change inputs or outcomes. They may artificially increase the status attached to their jobs or distort others’ perceived rewards to bring equity into balance.

- Leave the job. People who feel inequitably treated may decide to leave their jobs rather than suffer the inequity of being underpaid or overpaid. In their new jobs, they expect to find a more favorable balance of rewards.

The implication of equity theory for managers is that employees indeed evaluate the perceived equity of their rewards compared to others’. An increase in salary or a promotion will have no motivational effect if it is perceived as inequitable relative to that of other employees.

At Meadowcliff Elementary School in Little Rock, Arkansas, principal Karen Carter used the ideas of equity theory to devise a bonus system for teachers. Carter implemented several new programs designed to improve student learning, and she wanted to reward teachers for their efforts. To avoid fears of bias or favoritism, Carter and the Public Educa- tion Foundation of Little Rock decided to use Stanford Achievement Test results as a basis for bonuses. For each student whose Stanford score rose up to 4 percent over the course of the year, the teacher involved would get $100; 5 percent to 9 percent, $200; 10 percent to

14 percent, $300; and more than 15 percent, $400. The school’s scores on the test rose by an average of 17 percent over the course of the year. The base line test gave teachers a way to analyze individual students’ strengths and weaknesses and tailor instruction for each stu- dent. And because teachers felt the bonus system was equitable, it proved to be a powerful incentive. Administrators think the bonus system is helping to retain the best teachers at Meadowcliff, which serves primarily low-income students.24 If bonuses were based on sub- jective judgment, some teachers would likely be concerned that rewards were not being distributed equitably.

Inequitable pay puts pressure on employees that is sometimes almost too great to bear. They attempt to change their work habits, try to change the system, or leave the job.25

Consider Deb Allen, who went into the office on a weekend to catch up on work and found a document accidentally left on the copy machine. When she saw that some new hires were earning $200,000 more than their counterparts with more experience, and that “a noted screw-up” was making more than highly competent people, Allen began questioning why she was working on weekends for less pay than many others were receiving. Allen became so demoralized by the inequity that she quit her job three months later.26

2. EXPECTANCY THEORY

Expectancy theory suggests that motivation depends on individuals’ expectations about their ability to perform tasks and receive desired rewards. Expectancy theory is associated with the work of Victor Vroom, although a number of scholars have made contributions in this area.27 Expectancy theory is concerned not with identifying types of needs but with the thinking process that individuals use to achieve rewards. Consider Amy Huang, a univer- sity student with a strong desire for a B in her accounting course. Amy has a C+ average and one more exam to take. Amy’s motivation to study for that last exam will be influenced by (1) the expectation that hard study will lead to an A on the exam and (2) the expectation that an A on the exam will result in a B for the course. If Amy believes she cannot get an A on the exam or that receiving an A will not lead to a B for the course, she will not be motivated to study exceptionally hard.

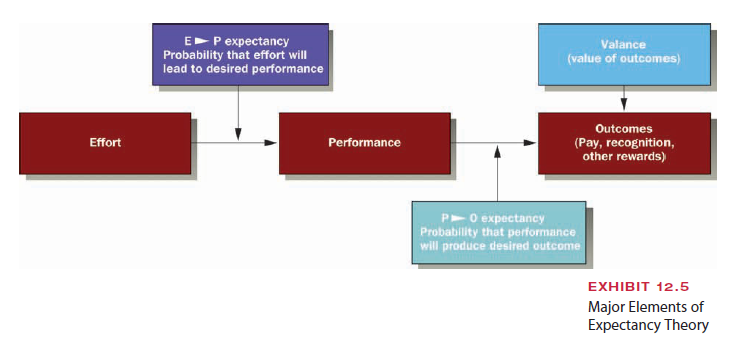

Elements of Expectancy Theory. Expectancy theory is based on the rela- tionship among the individual’s effort, the individual’s performance, and the desirability of outcomes associated with high performance. These elements and the relationships among them are illustrated in Exhibit 12.5. The keys to expectancy theory are the expectancies for the relationships among effort, performance, and the value of the outcomes to the individual.

E -> P expectancy involves determining whether putting effort into a task will lead to high performance. For this expectancy to be high, the individual must have the ability, previous experience, and necessary machinery, tools, and opportunity to perform. For Amy Huang to get a B in the accounting course, the E P expectancy is high if Amy truly be- lieves that with hard work, she can get an A on the final exam. If Amy believes she has nei- ther the ability nor the opportunity to achieve high performance, the expectancy will be low, and so will be her motivation.

P ->O expectancy involves determining whether successful performance will lead to the desired outcome. In the case of a person who is motivated to win a job-related award, this expectancy concerns the belief that high performance will truly lead to the award. If the P O expectancy is high, the individual will be more highly motivated. If the expectancy is that high performance will not produce the desired outcome, motivation will be lower. If an A on the final exam is likely to produce a B in the accounting course, Amy Huang’s P O expectancy will be high. Amy might talk to the professor to see whether an A will be sufficient to earn her a B in the course. If not, she will be less motivated to study hard for the final exam.

Valence is the value of outcomes, or attraction to outcomes, for the individual. If the outcomes that are available from high effort and good performance are not valued by employees, motivation will be low. Likewise, if outcomes have a high value, motivation will be higher.

Expectancy theory attempts not to define specific types of needs or rewards but only to establish that they exist and may be different for every individual. One employee might want to be promoted to a position of increased responsibility, and another might have high va- lence for good relationships with peers. Consequently, the first person will be motivated to work hard for a promotion and the second for the opportunity of a team position that will keep him or her associated with a group. Recent studies by the Gallup Organization sub- stantiate the idea that rewards need to be individualized to be motivating. A recent finding from the U.S. Department of Labor shows that the number 1 reason people leave their jobs is because they “don’t feel appreciated.” Yet Gallup’s analysis of 10,000 work groups in 30 industries found that making people feel appreciated depends on finding the right kind of reward for each individual. Some people prefer tangible rewards or gifts, whereas others place high value on words of recognition. In addition, some want public recognition, whereas others prefer to be quietly praised by someone they admire and respect.28 Many of today’s managers are also finding that praise and recognition from one’s peers often means more than a pat on the back from a supervisor, so they are implementing peer-recognition pro- grams that encourage employees to applaud one another for accomplishments.29

A simple sales department example illustrates how the expectancy model in Exhibit 12.5 works. If Carlos, a salesperson at the Diamond Gift Shop, believes that increased selling ef- fort will lead to higher personal sales, we can say that he has a high E P expectancy. Moreover, if Carlos also believes that higher personal sales will lead to a promotion or pay raise, we can say that he has a high P O expectancy. Finally, if Carlos places a high value on the promotion or pay raise, valence is high, and he will have a high motivational force. On the other hand, if either the E P or P O expectancy is low, or if the money or promotion has low valence for Carlos, the overall motivational force will be low. For an em- ployee to be highly motivated, all three factors in the expectancy model must be high.30

Implications for Managers. The expectancy theory of motivation is similar to the path–goal theory of leadership described in Chapter 11. Both theories are personalized to subordinates’ needs and goals. Managers’ responsibility is to help subordinates meet their needs and at the same time attain organizational goals. Managers try to find a match between a subordinate’s skills and abilities, job demands, and available rewards. To increase motivation, managers can clarify individuals’ needs, define the outcomes available from the organization, and ensure that each individual has the ability and support (namely, time and equipment) needed to attain outcomes.

Some companies use expectancy theory principles by designing incentive systems that identify desired organizational outcomes and give everyone the same shot at getting the re- wards. The trick is to design a system that fits with employees’ abilities and needs. When goal-setting isn’t used, results can be disastrous, as shown in the Business Blooper.

3. GOAL-SETTING THEORY

Recall from Chapter 5 our discussion of the importance and purposes of goals. Numerous studies have shown that people are more motivated when they have specific targets or objec- tives to work toward.31 You have probably noticed in your own life that you are more moti- vated when you have a specific goal, such as making an A on a final exam, losing 10 pounds before spring break, or earning enough money during the summer to buy a used car.

Goal-setting theory, described by Edwin Locke and Gary Latham, proposes that managers can increase motivation by setting specific, challenging goals that are accepted as valid by subordinates, and then helping people track their progress toward goal achieve- ment by providing timely feedback. The four key components of goal-setting theory in- clude the following:32

- Goal specificity refers to the degree to which goals are concrete and unambiguous. Specific goals such as “Visit one new customer each day,” or “Sell $1,000 worth of merchandise a week” are more motivating than vague goals such as “Keep in touch with new customers” or “Increase merchandise sales.” The first, critical step in any pay-for-performance sys- tem is to clearly define exactly what managers want people to accomplish. Lack of clear, specific goals is a major cause of the failure of incentive plans in many organizations.33

- In terms of goal difficulty, hard goals are more motivating than easy ones. Easy goals pro- vide little challenge for employees and don’t require them to increase their output. Highly ambitious but achievable goals ask people to stretch their abilities.

- Goal acceptance means that employees have to “buy into” the goals and be committed to them. Managers often find that having people participate in setting goals is a good way to increase acceptance and commitment. At Aluminio del Caroni, a state-owned alumi- num company in southeastern Venezuela, plant workers felt a renewed sense of commit- ment when top leaders implemented a co-management initiative that has managers and lower-level employees working together to set budgets, determine goals, and make deci- sions. “The managers and the workers are running this business together,” said one employee who spends his days shoveling molten aluminum down a channel from an industrial oven to a cast. “It gives us the motivation to work hard.” 34

- Finally, the component of feedback means that people get information about how well they are doing in progressing toward goal achievement. It is important for managers to provide performance feedback on a regular, ongoing basis. However, self-feedback, where people are able to monitor their own progress toward a goal, has been found to be an even stronger motivator than external feedback.35

Managers at Advanced Circuits of Aurora, Colorado, which makes custom-printed cir- cuit boards, steer employee performance toward goals by giving everyone ongoing numeri- cal feedback about every aspect of the business. Employees are so fired up that they check the data on the intranet throughout the day as if they were checking the latest sports scores. The system enables people to track their progress toward achieving goals, such as reaching sales targets or solving customer problems within specified time limits. “The more goals we get, the better it is for us,” says employee Barb Frevert. “The more we do for Ron, the more he does for us.”36

Why does goal setting increase motivation? For one thing, it enables people to focus their energies in the right direction. People know what to work toward, so they can direct their efforts toward the most important activities to accomplish the goals. Goals also ener- gize behavior because people feel compelled to develop plans and strategies that keep them focused on achieving the target. Specific, difficult goals provide a challenge and encourage people to put forth high levels of effort. In addition, when goals are achieved, pride and satisfaction increase, contributing to higher motivation and morale.39 One company that learned to use these principles is Best Buy.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

We’re a bunch of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our community. Your web site provided us with useful information to work on. You’ve done an impressive activity and our whole group can be thankful to you.

As a Newbie, I am permanently browsing online for articles that can aid me. Thank you