Defining and communicating an organization’s strategic objectives is a key element of any strategy process model since (1) the strategy definition and implementation elements of strategy must be directed at how best to achieve the objectives, (2) the overall success of e-business strategy will be assessed by comparing actual results against objectives and taking action to improve strategy and (3) clear, realistic objectives help communicate the goals and significance of an e-business initiative to employees and partners. Note that objective setting typically takes place in parallel with strategic analysis, defining a vision and strategy for e-business as part of an iterative process.

Figure 5.11 highlights some of the key aspects of strategic objective setting that will be covered in this section.

1. Defining vision and mission

Corporate vision is defined in Lynch (2000) as ‘a mental image of the possible and desirable future state of the organization’. A clear vision provides a summary for the development of purpose and strategy of the organization. Defining a specific company vision for e-business is helpful since it contextualizes e-business in relation to a company’s strategic initiatives (business alignment) and its marketplace. It also helps give a long-term emphasis on e-business transformation initiatives within an organization.

Vision or mission statements for e-businesses are a concise summary defining the scope and broad aims of digital channels in the future, explaining how they will contribute to the organization and support customers and interactions with partners. Jelassi and Enders (2008) explain that developing a mission statement should provide definition of:

- Business scope (where?). Markets including products, customer segments and geographies where the company wants to compete online.

- Unique competencies (how?). A high-level view of how the company will position and differentiate itself in terms of e-business products or services.

- Values (why?). Less commonly included, this is an emotional element of the mission statement which can indicate what inspires the organization or its e-business initiative.

Many organizations have a top-level mission statement which is used to scope the ambition of the company and to highlight the success factors for the business.

Vision statements can also be used to define a longer-term, 2-to-5 year picture of how the channel will support the organization through defining strategic priorities. The disadvantage with brief vision statements such as those shown in Box 5.3 is that they can be generic, so it is best to develop a more detailed vision or make them as specific as possible by:

- Referencing key business strategy and industry issues and goals;

- Referencing aspects of online customer acquisition, conversion or experience and retention;

- Making memorable through acronyms or mnemonics, e.g. the 123 of our digital strategy, the 8 Cs of our online value proposition;

- Linking through to objectives and strategies to achieve them through high-level goals.

Dell expands on the simple vision outline in the box to explain:

Our core business strategy is built around our direct customer model, relevant technologies and solutions, and highly efficient manufacturing and logistics; and we are expanding that core strategy by adding new distribution channels to reach even more commercial customers and individual consumers around the world. Using this strategy, we strive to provide the best possible customer experience by offering superior value; high-quality, relevant technology; customized systems and services; superior service and support; and differentiated products and services that are easy to buy and use.

An example of a more detailed vision statement for a multi-channel retailer might read:

Our digital channels will make it easy for shoppers to find, compare and select products using a structured approach to merchandising and improving conversion to produce an experience rated as excellent by the majority of our customers.

Different aspects of the vision statement (underlined) can then be expanded upon when discussing with colleagues, e.g.

- Digital channels = the web site supported by e-mail and mobile messaging

- Find = improvements to site search functionality

- Compare and select = using detailed product descriptions, rich media and ratings

- Merchandising and improving conversion = through delivery of automated merchandising facilities to present relevant offers to maximize conversion and average order value. Additionally, use of structured testing techniques such as AB testing (see Chapter 12) and multivariate testing will be used

- Experience rated as excellent = we will regularly review customer satisfaction and advocacy against direct competitors and out-of-sector to drive improvements with the web site.

Scenario-based analysis is a useful approach to discussing alternative visions of the future prior to objective setting. Lynch (2000) explains that scenario-based analysis is concerned with possible models of the future of an organization’s environment. He says:

The aim is not to predict, but to explore a set of possibilities; scenarios take different situations with different starting points.

Lynch distinguishes qualitative scenario-based planning from quantitative prediction based on demand analysis, for example. In an e-business perspective, scenarios that could be explored include:

- One player in our industry becomes dominant through use of the Internet.

- Major customers do not adopt e-commerce due to organizational barriers.

- Major disintermediation (Chapter 2) occurs in our industry.

- B2B marketplaces do or do not become dominant in our industry.

- New entrants or substitute products change our industry.

Through performing this type of analysis, better understanding of the drivers for different views of the future will result, new strategies can be generated and strategic risks can be assessed. It is clear that the scenarios above will differ between worst-case and best-case scenarios.

Simons (2000a), in referring to the vision of Barclays Bank, illustrates the change in thinking required for e-business vision. He reports that to execute the vision of the bank ‘a high tolerance of uncertainty’ must be introduced. The group CEO of Barclays (Matt Barrett) said:

our objective is to use technology to develop entirely new business models … while transforming our internal structure to make us more efficient and effective. Any strategy that does not achieve both is fundamentally flawed.

Speaking at E-metrics 2008, Julian Brewer, Head of Online Sales and Content, Barclays UK Retail Banking explained how Barclays Bank was using digital technology today to make their e-commerce more efficient and effective, including:

- Using predictive web analytics (see Chapter 12) which connects online data to effective action by drawing reliable conclusions about current conditions and future events;

- Advanced tracking of different online media across customer touchpoints, in particular paid search such as Google AdWords which accounts for 60% of Barclays spend on digital media.

Benefits in 2006 were a 5% improvement in paid search costs worth £400k in saved costs (showing that around £8 million annually were spent on paid search and the importance of developing a search engine marketing strategy). An additional 6% of site traffic was generated by applying analytics to improve search practice equating to £1.3 million income (Brewer, 2008).

From a sell-side e-commerce perspective, a key aspect of vision is how the Internet will primarily complement the company’s other channels or whether it will replace other channels. Whether the vision is to complement or replace it is important to communicate this to staff and other stakeholders such as customers, suppliers and shareholders.

Clearly, if it is believed that e-commerce will primarily replace other channels, then it is important to invest in the technical, human and organizational resources to achieve this. Kumar (1999) suggests that replacement is most likely to happen when:

- customer access to the Internet is high;

- the Internet can offer a better value proposition than other media (i.e. propensity to purchase online is high);

- the product can be delivered over the Internet (it can be argued that this is not essential for replacement);

- the product can be standardized (user does not usually need to view to purchase).

If at least two of Kumar’s conditions are met there may be a replacement effect. For example, purchase of travel services or insurance online fulfils criteria 1, 2 and 4. As a consequence, physical outlets for these products may no longer be viable since the service can be provided in a cheaper, more convenient form online. The closure of British Airways travel retail units and AA shops is indicative of this change, with the business being delivered completely by a phone or online sales channel. The extent to which these conditions are met will vary through time, for example as access to the Internet and propensity to purchase online increase. A similar test is de Kare-Silver’s (2000) Electronic Shopping Test (Chapter 8, p. 435).

A similar vision of the future can be developed for buy-side activities such as procurement. A company can have a vision for how e-procurement and e-enabled supply chain management (SCM) will complement or replace paper-based procurement and SCM over a future time period.

2. How can e-business create business value?

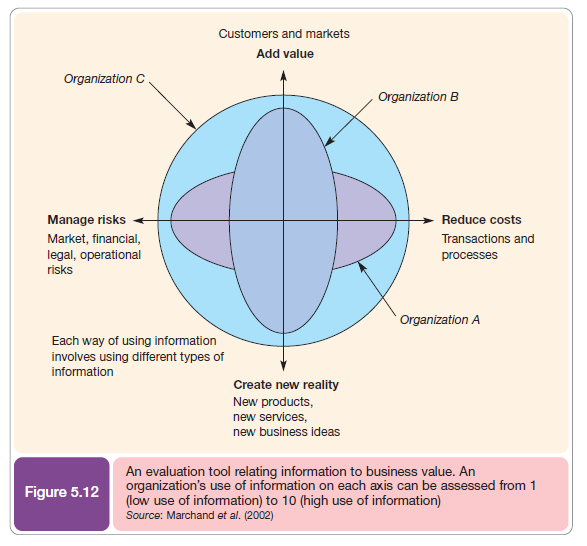

As Chaffey and Wood (2004) have emphasized, much of the organizational value created by e-business is due to more effective use of information. The strategic importance of business information management in an organization can be reviewed and communicated as part of vision using Figure 5.12. This analytic tool, devised by Professor Don Marchand, shows different ways in which information can create value for organizations.

The main methods are:

- Adding value. Value is added through providing better-quality products and services to an organization’s customers. Information can be used to better understand customer characteristics and needs and their level of satisfaction with services. Information is also used to sense and respond to markets. Information about trends in demands, competitor products and activities must be monitored so organizations can develop strategies to compete in the marketplace. For example, all organizations will use databases to store personal characteristics of customers and details of their transaction history which shows when they have purchased different products, responded to marketing campaigns or used different online services. Analysis of these databases using data mining can then be used to understand customer preferences and market products that better meet their needs. Companies can use sense and respond communications. The classic example of this is the personalization facilities provided by Amazon where personal recommendations are provided.

- Reduce costs. Cost reduction through information is achieved through making the business processes shown in Figure 10.2 more efficient. Efficiency is achieved through using information to source, create, market and deliver services using fewer resources than previously. Technology is applied to reduce paperwork, reduce the human resources needed to operate the processes through automation and improve internal and external communications. Capital One (Case Study 5.1) has used Internet technology so that customers can apply for and service their credit cards online – the concept of ‘web self-service’.

- Manage risks. Risk management is a well-established use of information within organizations. Marchand (1999) notes how risk management within organizations has created different functions and professions such as finance, accounting, auditing and corporate performance management. For example, Capital One uses information to manage its financial risks and promotions through extensive modelling and analysis of customer behaviour.

- Create new reality. Marchand uses the expression ‘create new reality’ to refer to how information and new technologies can be used to innovate, to create new ways in which products or services can be developed. This is particularly apt for e-business. Capital One has used technology to facilitate the launch of flexible new credit products which are microtargeted to particular audiences.

3. Objective setting

Effective strategies link objectives, strategies and performance. One method of achieving this is through tabulation as shown for a fictitious company in Table 5.6. Each of the performance indicators should also have a timeframe in which to achieve these objectives. Despite the dynamism of e-business, some of the goals that require processes to be re-engineered cannot be achieved immediately. Prioritization of objectives, in this case from 1 to 6, can help in communicating the e-business vision to staff and also when allocating resources to achieve the strategy. As with other forms of strategic objectives, e-business objectives should be SMART (Box 5.4) and include both efficiency and effectiveness measures.

Put simply, efficiency is ‘doing the thing right’ – it defines whether processes are completed using the least resources and in the shortest time possible. Effectiveness is ‘doing the right thing’. ‘Doing the right thing’ means conducting the right activities and applying the best strategies for competitive advantage. From a process viewpoint it is producing the required outputs and outcomes, in other words meeting objectives. When organizations set goals for e-business and e-commerce, there is a tendency to focus on the efficiency metrics such as time to complete a process and reducing costs. Such measures often do not capture the overall value that can be derived from e-business. Effectiveness measures will assess how many customers or partners are using the e-business services and the incremental benefits that contribute to profitability. For example, an airline such as BA.com could use its e-channel services to reduce costs (increased efficiency), but could be facing a declining share of online bookers (decreased effectiveness). Effectiveness may also refer to the relative importance of objectives for revenue generation through online sales and improving internal process or supply chain efficiency. It may be more effective to focus on the latter.

As for improving any aspect of business performance, performance management systems are needed to monitor, analyse and refine the performance of an organization. The use of systems such as web analytics in achieving this is covered in Chapter 12.

3.1. The online revenue contribution

By considering the demand analysis, competitor analysis and factors such as those defined by Kumar (1999) an Internet or online revenue contribution (ORC) objective can be set.

This key e-business objective states the percentage of company revenue directly generated through online transactions. However, for some companies such as B2B service companies, it is unrealistic to expect a high direct online contribution. In this case, an indirect online contribution can be stated; this is where the sale is influenced by the online presence but purchase occurs using conventional channels, for example a customer selecting a product on a web site and then phoning to place the order. Online revenue contribution objectives can be specified for different types of products, customer segments and geographic markets. They can also be set for different digital channels such as web or mobile commerce.

3.2. Conversion modelling for sell-side e-commerce

Experienced e-commerce managers build conversion or waterfall models of the efficiency of their web marketing to assist with forecasting future sales. Using this approach, the total online demand for a service in a particular market can be estimated and then the success of the company in achieving a share of this market determined. Conversion marketing tactics can then be created to convert as many potential site visitors into actual visitors and then convert these into leads, customers and repeat customers as explained in later chapters on online marketing. Box 5.5gives further details.

So, to assess the potential impact of digital channels it is useful to put in place tracking or research which assesses the cross-channel conversions at different stages in the buying process. For example, phone numbers which are unique to the web site can be used as an indication of the volume of callers to a contact centre influenced by the web site. This insight can then be built into budget models of sales levels such as that shown in Figure 5.14. This shows that of the 100,000 unique visitors in a period we can determine that 5,000 (5%) may actually become offline leads.

Another important type of high-level contribution objective is the e-channel service contribution. This gives an indication of the proportion of service-type processes that are completed using electronic channels. Examples include e-service (proportion of customers who use web self-service), e-procurement (proportion of different types of purchases bought online) and administrative process facilities used via an intranet or extranet.

An equivalent buy-side measure to the online revenue contribution is the proportion of procurement that is achieved online. This can be broken down into the proportions of electronic transactions for ordering, invoicing, delivery and payment, as described in Chapter 7. Deise et al. (2000) note that the three business objectives for procuring materials and services should be improving supplier performance, reducing cycle time and cost for indirect procurement, and reducing total acquisition costs. Metrics can be developed for each of these.

3.3. The balanced scorecard approach to objective setting

Integrated metrics such as the balanced scorecard have become widely used as a means of translating organizational strategies into objectives and then providing metrics to monitor the execution of the strategy. Since the balanced business scorecard is a well-known and widely used framework, it can be helpful to define objectives for e-business in the categories below.

The balanced scorecard, popularized in a Harvard Business Review article by Kaplan and Norton (1993), can be used to translate vision and strategy into objectives. In part, it was a response to over-reliance on financial metrics such as turnover and profitability and a tendency for these measures to be retrospective rather than looking at future potential as indicated by innovation, customer satisfaction and employee development. In addition to financial data, the balanced scorecard uses operational measures such as customer satisfaction, efficiency of internal processes and also the organization’s innovation and improvement activities including staff development.

The main areas of the balanced scorecard are:

- Customer concerns. These include time (lead time, time to quote, etc.), quality, performance, service and cost. Example measures from Halifax Bank from Olve (1999): satisfaction of mystery shoppers visiting branches and from branch customer surveys.

- Internal measures. Internal measures should be based on the business processes that have the greatest impact on customer satisfaction: cycle time, quality, employee skills, productivity. Companies should also identify critical core competencies and try to guarantee market leadership. Example measures from Halifax Bank: ATM availability (%), conversion rates on mortgage applications (%), arrears on mortgage (%).

- Financial measures. Traditional measures such as turnover, costs, profitability and return on capital employed. For publicly quoted companies this measure is key to shareholder value. Example measures from Halifax Bank: gross receipts (£), mortgage offers (£), loans (£).

- Learning and growth: innovation and staff development. Innovation can be measured by change in value through time (employee value, shareholder value, percentage and value of sales from new products). Examples: management performance, training performance, new product development.

For each of these four areas management teams will define objectives, specific measures, targets and initiatives to achieve these targets. For some companies, such as Skandia Life, the balanced scorecard becomes much more than a performance measurement system and provides a framework for the entire business strategy process. Olve et al. (1999) make the point that a further benefit of the scorecard is that it does not solely focus on outcomes, but also considers measures that are performance drivers that should positively affect the outcomes. For example, investment in technology and in employee training are performance drivers.

More recently, as the scorecard has been widely used, it has been suggested that it provides a useful tool for aligning business and IS strategy, see for example der Zee and de Jong (1999).

Table 5.8 outlines how the balanced scorecard could be deployed in a B2B organization to support its e-business strategy. A more detailed example of how the balanced scorecard can be used for specific e-business processes such as Internet marketing is given in Chapter 8.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

My spouse and I stumbled over here by a different page and thought I might as well check things out. I like what I see so now i am following you. Look forward to going over your web page yet again.