Our entire discussion of methods of capital budgeting has rested on the proposition that the wealth of a firm’s shareholders is highest if the firm accepts every project that has a positive net present value. Suppose, however, that there are limitations on the investment program that 9In Chapter 22, we discuss when it may pay a company to delay undertaking a positive-NPV project. We will see that when projects are “deep-in-the-money” (project A), it generally pays to invest right away and capture the cash flows. However, in the case of projects that are “close-to-the-money” (project B), it makes more sense to wait and see.

prevent the company from undertaking all such projects. Economists call this capital rationing. When capital is rationed, we need a method of selecting the package of projects that is within the company’s resources yet gives the highest possible net present value.

1. An Easy Problem in Capital Rationing

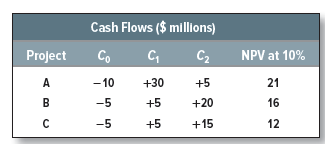

Let us start with a simple example. The opportunity cost of capital is 10%, and our company has the following opportunities:

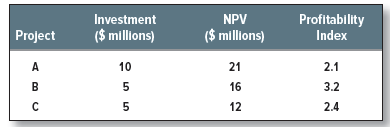

All three projects are attractive, but suppose that the firm is limited to spending $10 million. In that case, it can invest either in project A or in projects B and C, but it cannot invest in all three. Although individually B and C have lower net present values than project A, when taken together they have the higher net present value. Here we cannot choose between projects solely on the basis of net present values. When money is limited, we need to concentrate on getting the biggest bang for our buck. In other words, we must pick the projects that offer the highest net present value per dollar of initial outlay. This ratio is known as the profitability index:10

![]()

For our three projects the profitability index is calculated as follows:11

Project B has the highest profitability index and C has the next highest. Therefore, if our budget limit is $10 million, we should accept these two projects.[1] [2] [3]

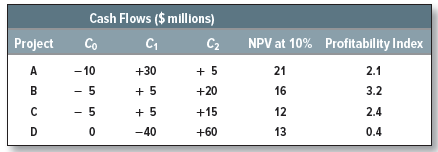

Unfortunately, there are some limitations to this simple ranking method. One of the most serious is that it breaks down whenever more than one resource is rationed.[4] For example, suppose that the firm can raise only $10 million for investment in each of years 0 and 1 and that the menu of possible projects is expanded to include an investment next year in project D:

One strategy is to accept projects B and C; however, if we do this, we cannot also accept D, which costs more than our budget limit for period 1. An alternative is to accept project A in period 0. Although this has a lower net present value than the combination of B and C, it provides a $30 million positive cash flow in period 1. When this is added to the $10 million budget, we can also afford to undertake D next year. A and D have lower profitability indexes than B and C, but they have a higher total net present value.

The reason that ranking on the profitability index fails in this example is that resources are constrained in each of two periods. In fact, this ranking method is inadequate whenever there is any other constraint on the choice of projects. This means that it cannot cope with cases in which two projects are mutually exclusive or in which one project is dependent on another.

For example, suppose that you have a long menu of possible projects starting this year and next. There is a limit on how much you can invest in each year. Perhaps also you can’t undertake both project alpha and beta (they both require the same piece of land), and you can’t invest in project gamma unless you also invest in delta (gamma is simply an add-on to delta). You need to find the package of projects that satisfies all these constraints and gives the highest NPV.

One way to tackle such a problem is to work through all possible combinations of projects. For each combination you first check whether the projects satisfy the constraints and then calculate the net present value. But it is smarter to recognize that linear programming (LP) techniques are specially designed to search through such possible combinations.

2. Uses of Capital Rationing Models

Linear programming models seem tailor-made for solving capital budgeting problems when resources are limited. Why then are they not universally accepted either in theory or in practice? One reason is that these models can turn out to be very complex. Second, as with any sophisticated long-range planning tool, there is the general problem of getting good data. It is just not worth applying costly, sophisticated methods to poor data. Furthermore, these models are based on the assumption that all future investment opportunities are known. In reality, the discovery of investment ideas is an unfolding process.

Our misgivings center in part on the basic assumption that capital is limited. This may often be the case in countries such as China and India with financial markets that are not as fully developed as those in the United States, Europe, and Japan, but, when we come to discuss company financing, we shall see that large corporations in the latter economies do not face capital rationing and can raise large sums of money on fair terms. Why then do many company presidents in these countries tell their subordinates that capital is limited? If they are right, the financial markets are seriously imperfect. What then are they doing maximizing

NPV?[5] We might be tempted to suppose that if capital is not rationed, they do not need to use linear programming and, if it is rationed, then surely they ought not to use it. But that would be too quick a judgment. Let us look at this problem more deliberately.

Soft Rationing Many firms’ capital constraints are “soft.” They reflect no imperfections in financial markets. Instead they are provisional limits adopted by management as an aid to financial control.

Some ambitious divisional managers habitually overstate their investment opportunities. Rather than trying to distinguish which projects really are worthwhile, headquarters may find it simpler to impose an upper limit on divisional expenditures and thereby force the divisions to set their own priorities. In such instances, budget limits are a rough but effective way of dealing with biased cash-flow forecasts. In other cases, management may believe that very rapid corporate growth could impose intolerable strains on management and the organization. Since it is difficult to quantify such constraints explicitly, the budget limit may be used as a proxy.

Because such budget limits have nothing to do with any inefficiency in the financial market, there is no contradiction in using an LP model in the division to maximize net present value subject to the budget constraint. On the other hand, there is not much point in elaborate selection procedures if the cash-flow forecasts of the division are seriously biased.

Even if capital is not rationed, other resources may be. The availability of management time, skilled labor, or even other capital equipment often constitutes an important constraint on a company’s growth. In such cases also there is no contradiction in using an LP model to select the package of projects that maximizes NPV.

Hard Rationing Soft rationing should never cost the firm anything. If capital constraints become tight enough to hurt—in the sense that projects with significant positive NPVs are passed up—then the firm raises more money and loosens the constraint. But what if it can’t raise more money—what if it faces hard rationing?

Hard rationing implies market imperfections, but that does not necessarily mean we have to throw away net present value as a criterion for capital budgeting. It depends on the nature of the imperfection.

Arizona Aquaculture Inc. (AAI) borrows as much as the banks will lend it, yet it still has good investment opportunities. This is not hard rationing so long as AAI can issue stock. But perhaps it can’t. Perhaps the founder and majority shareholder vetoes the idea from fear of losing control of the firm. Perhaps a stock issue would bring costly red tape or legal complications.[6]

This does not invalidate the NPV rule. AAI’s shareholders can borrow or lend, sell their shares, or buy more. They have free access to security markets. The type of portfolio they hold is independent of AAI’s financing or investment decisions. The only way AAI can help its shareholders is to make them richer. Thus, AAI should invest its available cash in the package of projects having the largest aggregate net present value.

A barrier between the firm and financial markets does not undermine net present value so long as the barrier is the only market imperfection. The important thing is that the firm’s shareholders have free access to well-functioning financial markets.

The net present value rule is undermined when imperfections restrict shareholders’ portfolio choice. Suppose that Nevada Aquaculture Inc. (NAI) is solely owned by its founder,

Alexander Turbot. Mr. Turbot has no cash or credit remaining, but he is convinced that expansion of his operation is a high-NPV investment. He has tried to sell stock but has found that prospective investors, skeptical of prospects for fish farming in the desert, offer him much less than he thinks his firm is worth. For Mr. Turbot, financial markets hardly exist. It makes little sense for him to discount prospective cash flows at a market opportunity cost of capital.

23 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021