The shareholders are the owners of the firm. But most shareholders do not feel like the boss, and with good reason. Try buying one share of IBM stock and marching into the boardroom for a chat with your employee, the CEO. (However, if you own 50 million IBM shares, the CEO will travel to see you.)

The ownership and management of large corporations are separated. Shareholders elect the board of directors but have little direct say in most management decisions. Agency costs arise when managers or directors are tempted to make decisions that are not in the shareholders’ interests.

As we pointed out in Chapter 1, there are many forces and constraints working to keep managers’ and shareholders’ interests in line. But what can be done to ensure that the board has engaged the most talented managers? What happens if managers are inadequate? What if the board is derelict in monitoring the performance of managers? Or what if the firm’s managers are fine but the resources of the firm could be used more efficiently by merging with another firm? Can we count on managers to pursue policies that might put them out of a job?

These are all questions about the market for corporate control, the mechanisms by which firms are matched up with owners and management teams who can make the most of the firm’s resources. You should not take a firm’s current ownership and management for granted. If it is possible for the value of the firm to be enhanced by changing management or by reorganizing under new owners, there will be incentives for someone to make the change.

There are three ways to change the management of a firm: (1) a successful proxy contest in which a group of shareholders votes in a new board of directors who then pick a new management team, (2) a takeover of one company by another, and (3) a leveraged buyout of the firm by a private group of investors. We focus here on the first two methods and postpone discussion of buyouts until the next chapter.

1. Proxy Contests

Shareholders elect the board of directors to keep watch on management and replace unsatisfactory managers. If the board is lax, shareholders are free to elect a different board.

When a group of investors believes that the board and its management should be replaced, they can launch a proxy contest at the next annual meeting. A proxy is the right to vote another shareholder’s shares. In a proxy contest, the dissident shareholders attempt to obtain enough proxies to elect their own slate to the board of directors. Once the new board is in control, management can be replaced and company policy changed. A proxy fight is therefore a direct contest for control of the corporation. Many proxy fights are initiated by major shareholders who consider the firm poorly managed. In other cases a fight may be a prelude to the merger of two firms. The proponent of the merger may believe that a new board will better appreciate the advantages of combining the two firms.

Proxy contests are expensive and difficult to win. Dissidents who engage in proxy fights must use their own money, but management can use the corporation’s funds and lines of communications with shareholders to defend itself. To level the playing field somewhat, the SEC has introduced new rules to make it easier to mount a proxy fight.

Institutional shareholders, such as large hedge funds, have become more aggressive in pressing for managerial accountability and have been able to gain concessions by initiating proxy fights. For example, in 2017, hedge fund manager Nelson Peltz sought to persuade Procter & Gamble to make changes to its corporate structure and its brand policy. After failing to persuade management to offer him a board seat, he launched a proxy battle. The contest cost the two sides a reported $60 million and resulted in a victory for Peltz by a margin of .002%. Peltz believed that as a board member, he would be better placed to secure reforms.

2. Takeovers

The alternative to a proxy fight is for the would-be acquirer to make a tender offer directly to the shareholders. If the offer is successful, the new owner is free to make any management changes. The management of the target firm may advise its shareholders to accept the offer, or it may fight the bid in the hope that the acquirer will either raise its offer or throw in the towel.

In the United States, the rules for tender offers are set largely by the Williams Act of 1968 and by state laws. The Williams Act obliges firms that own 5% or more of another company’s shares to tip their hand by reporting their holding to the SEC and to outline their intentions in a Schedule 13(d) filing. This filing is often an invitation for other bidders to enter the fray and to force up the takeover premium. The consolation for the initial bidder is that if its bid is ultimately unsuccessful, it may be able to sell off its holding in the target at a substantial profit.

The courts act as a referee to see that contests are conducted fairly. The problem in setting these rules is that it is unclear who requires protection. Should the management of the target firm be given more weapons to defend itself against unwelcome predators? Or should it simply be encouraged to sit the game out? Or should it be obliged to conduct an auction to obtain the highest price for its shareholders?[1] And what about would-be acquirers? Should they be forced to reveal their intentions at an early stage, or would that allow other firms to piggyback on their good ideas by entering bids of their own? Keep these questions in mind as we review a recent takeover battle.

3. Valeant Bids for Allergan

Allergan is a U.S. specialty pharmaceutical company, best known as the maker of Botox. In 2014, its independence was threatened by the Canadian firm, Valeant, which, in an unusual move, teamed up with the hedge fund, Pershing Square, to acquire Allergan. Between February and April 2014, Bill Ackman, the manager of Pershing, built up a holding of 9.7% of Allergan’s shares. Then on April 21, Valeant announced its offer for Allergan of $47 billion in a mixture of stock and cash, a premium of about 17% over Allergan’s previous day’s market value.

Allergan’s management rejected the offer as undervaluing the company. It accused Valeant of following a strategy of gobbling up acquisitions and starving them of funds. In turn, Valeant accused Allergan’s management of spending too freely on research and development and on sales and marketing. It promised that it would cut the combined company’s R&D spending by more than two-thirds.

As soon as Allergan became aware of Valeant’s offer, the board sought to protect itself by putting in place a poison pill. If any single shareholder acquired a holding of more than 10% of Allergan stock, the poison pill would allow Allergan to offer its other shareholders additional shares at a substantial discount. The immediate effect of Allergan’s pill was to stop Pershing from increasing its holding.

In May, Valeant moved to anticipate any antitrust objections to the merger by selling off the rights to some of its skin care products that competed with Allergan’s. It then raised its offer to $49.4 billion, and three days later, raised it again to $53 billion. Subsequently, in October, Valeant wrote to Allergan that it was prepared to raise its offer to at least $59 billion, though it stopped short of actually doing so.

As Allergan’s board continued to reject Valeant’s offers, Pershing proposed to call a special meeting of Allergan’s shareholders to replace the board with new members who would be more receptive to Valeant’s bid. Such a meeting would require the support of 25% of Allergan’s shareholders. Because the poison pill effectively grouped together any shareholders who acted jointly, Pershing needed to be sure that any demand for a special meeting would not trigger the poison pill. Whether Pershing would get the necessary support depended heavily on the response of arbitrageurs who owned at least 20% of Allergan’s shares.[2]

In the end, Pershing did not need the support of Allergan’s shareholders for a special meeting. Allergan settled the pending litigation by agreeing to hold the meeting in December, giving Pershing the chance to attempt its threatened replacement of Allergan’s board.

But not everything was going well for Pershing and Valeant. In November 2014, a federal district court ruled that there were serious questions as to whether Pershing’s collaboration with Valeant involved insider trading and enjoined Pershing Square from voting its shares at Allergan’s special meeting unless it disclosed the facts underlying its exposure to liability for insider trading.

Although the poison pill could not prevent Pershing from calling the special meeting to unseat Allergan’s directors, it did give Allergan breathing space. So, while the parties were fighting their battles in the courts, Allergan started looking around for a more congenial partner. At first, it thought it had found one in Salix Pharmaceuticals. A combined company of Allergan and Salix would have been too large a fish for Valeant to swallow. Reports of the negotiations with Salix led Pershing to threaten that if Allergan went ahead with a bid for Salix, Pershing would immediately bring litigation against Allergan’s board for breach of fiduciary duty. But by then, Allergan had become disenchanted with the possible Salix merger. Shortly afterward, it found a more attractive partner in Actavis. In November 2014, Allergan agreed to a $66 billion offer from Actavis, and the long, acrimonious battle for Allergan was finally over.

Postscript: Allergan still continued to make the headlines. After the merger, Actavis sold off much of its existing business and changed its name to Allergan. In 2015, Allergan again found itself involved in a merger negotiation as the pharmaceutical giant Pfizer launched, but subsequently withdrew, a friendly $160 billion bid for the company.

Valeant also stayed in the news, but it was not news that its shareholders wanted to hear. Its shares plummeted more than 90% after the company uncovered accounting irregularities, warned of a potential default on its $30 billion of debt, and revealed it was under investigation by the SEC.

4. Takeover Defenses

What are the lessons from the battle for Allergan? First, the example illustrates some of the strategies of modern merger warfare. Firms such as Allergan that are worried about being taken over usually prepare their defenses in advance. Often they persuade shareholders to agree to shark-repellent changes to the corporate charter. For example, the charter may be amended to require that any merger must be approved by a supermajority of 80% of the shares rather than the normal 50%. Although shareholders are generally prepared to go along with management’s proposals, it is doubtful whether such shark-repellent defenses are truly in their interest. Managers who are protected from takeover appear to enjoy higher remuneration and to generate less wealth for their shareholders.

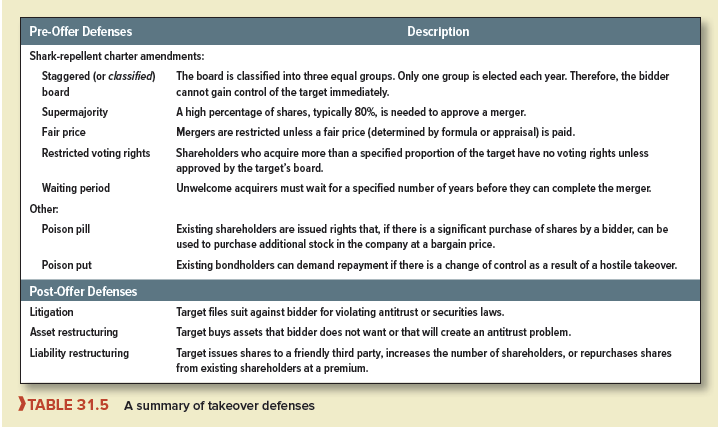

Many firms follow Allergan’s example and deter potential bidders by devising poison pills that make the company unappetizing. For example, the poison pill may give existing shareholders the right to buy the company’s shares at half price as soon as a bidder acquires more than 15% of the shares. The bidder is not entitled to the discount. Thus, the bidder resembles Tantalus—as soon as it has acquired 15% of the shares, control is lifted away from its reach. These and other lines of defense are summarized in Table 31.5.

Why did Allergan’s management contest the takeover bid? One possible reason was to extract a higher price for the stock, for Valeant was twice led to raise its offer. But on other occasions the target’s management may reject a bid because it wishes to protect its position within the firm. Companies sometimes reduce these conflicts of interest by offering their managers golden parachutes—that is, generous payoffs if the managers lose their jobs as a result of a takeover. It may seem odd to reward managers for being taken over. However, if a soft landing overcomes their opposition to takeover bids, a few million may be a small price to pay.

Any management team that tries to develop improved weapons of defense must expect challenge in the courts. In the early 1980s, the courts tended to give managers the benefit of the doubt and respect their business judgment about whether a takeover should be resisted. But the courts’ attitudes to takeover battles have shifted. For example, in 1993 a court blocked Viacom’s agreed takeover of Paramount on the grounds that Paramount directors did not do their homework before turning down a higher offer from QVC. Paramount was forced to give up its poison-pill defense and the stock options that it had offered to Viacom. Such decisions have led managers to become more careful in opposing bids, and they do not throw themselves blindly into the arms of any white knight.

At the same time, companies have acquired some new defensive weapons. In 1987, the Supreme Court upheld state laws that allow companies to deprive an investor of voting rights as soon as the investor’s share in the company exceeds a certain level. Since then, state antitakeover laws have proliferated. Many allow boards of directors to block mergers with hostile bidders for several years and to consider the interests of employees, customers, suppliers, and their communities in deciding whether to try to block a hostile bid.

Anglo-Saxon countries used to have a near-monopoly on hostile takeovers. That is no longer the case. Takeover activity in Europe often exceeds that in the United States, and in recent years, some of the most bitterly contested takeovers have involved European companies.

For example, Mittal’s $27 billion takeover of Arcelor resulted from a fierce and highly politicized five-month battle. Arcelor used every defense in the book—including inviting a Russian company to become a leading shareholder.

Mittal is now based in Europe, but it began operations in Indonesia. This illustrates another change in the merger market. Acquirers are also no longer confined to the major industrialized countries. They now include Brazilian, Indian, and Chinese companies. For example, Tetley Tea, Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus, and Jaguar and Land Rover have all been acquired by Indian conglomerate Tata Group. In China, Lenovo acquired IBM’s personal computer business, Geely bought Volvo from Ford, and China National Chemical bought Syngenta, the Swiss agrichemical busines. In Brazil, Vale purchased Inco, the Canadian nickel producer, and Cutrale-Safra bought the U.S. banana company Chiquita Brands.

5. Who Gains Most in Mergers?

As our brief history illustrates, in mergers sellers generally do better than buyers. Why do sellers earn higher returns? There are two reasons. First, buying firms are typically larger than selling firms. In many mergers, the buyer is so much larger that even substantial net benefits would not show up clearly in the buyer’s share price. Suppose, for example, that company A buys company B, which is only one-tenth A’s size. Suppose the dollar value of the net gain from the merger is split equally between A and B.[4] Each company’s shareholders receive the same dollar profit, but B’s receive 10 times A’s percentage return.

The second, and more important, reason is the competition among potential bidders. Once the first bidder puts the target company “in play,” one or more additional suitors often jump in, sometimes as white knights at the invitation of the target firm’s management. Every time one suitor tops another’s bid, more of the merger gain slides toward the target. At the same time, the target firm’s management may mount various legal and financial counterattacks, ensuring that capitulation, if and when it comes, is at the highest attainable price.

Identifying attractive takeover candidates and mounting a bid are high-cost activities. So why should anyone incur these costs if other bidders are likely to jump in later and force up the takeover premium? Mounting a bid may be more worthwhile if a company can first accumulate a holding in the target company. The Williams Act allows a company to acquire a toehold of up to 5% of the target’s shares before it is obliged to reveal its holding and outline its plans. So, even if the bid is ultimately unsuccessful, the company may be able to sell off its holding in the target at a substantial profit.

Bidders and targets are not the only possible winners. Other winners include investment bankers, lawyers, accountants, and in some cases arbitrageurs such as hedge funds, which speculate on the likely success of takeover bids.[5] “Speculate” has a negative ring, but it can be a useful social service. A tender offer may present shareholders with a difficult decision. Should they accept, should they wait to see if someone else produces a better offer, or should they sell their stock in the market? This dilemma presents an opportunity for hedge funds, which specialize in answering such questions. In other words, they buy from the target’s shareholders and take on the risk that the deal will not go through.

24 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

25 Jun 2021

23 Jun 2021

24 Jun 2021