1. PURPOSE OF THE THESIS

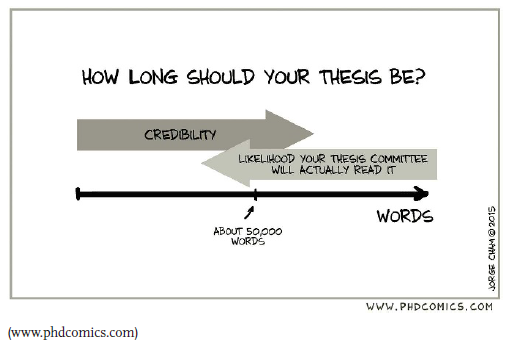

A Ph.D. thesis in the sciences is supposed to present the candidate’s original research. Its purpose is to prove that the candidate can do and communicate such research. Therefore, a thesis should exhibit the same type of disciplined writing that is required in a journal publication. Unlike a scientific paper, a thesis may address more than one topic, and it may present more than one approach to some topics. The thesis may present all or most of the data obtained in the student’s thesis-related research. Therefore, the thesis usually is longer and more involved than a scientific paper. But the concept that a thesis must be a bulky 200-page tome is wrong, dead wrong. Many 200-page theses contain only 50 pages of good science. The other 150 pages comprise turgid descriptions of insignificant details.

We have seen many Ph.D. theses, and we have assisted with the writing and organization of a good number of them. On the basis of this experience, we have concluded that there are almost no generally accepted rules for thesis preparation. Most types of scientific writing are highly structured. Thesis writing is not. The “right” way to write a thesis varies widely from institution to institution and even from professor to professor within the same department of the same institution.

Reid (1978) is one of many over the years who have suggested that the traditional thesis no longer serves a purpose. In Reid’s words, “Requirements that a candidate must produce an expansive traditional-style dissertation for a Ph.D. degree in the sciences must be abandoned. . . . The expansive traditional dissertation fosters the false impression that a typed record must be preserved of every table, graph, and successful or unsuccessful experimental procedure.” Indeed, in some settings, the core of a thesis now normally consists of scientific papers that the student has published.

If a thesis serves any real purpose, that purpose might be to determine literacy. Perhaps universities have always worried about what would happen to their image if a Ph.D. degree turned out to have been awarded to an illiterate. Hence, the thesis requirement. Stated more positively, the candidate has been through a process of maturation, discipline, and scholarship. The “ticket out” is a satisfactory thesis.

It may be useful to mention that theses at European universities have tended to be taken much more seriously. They are designed to show that the candidate has reached maturity and can both do science and write science. Such theses may be submitted after some years of work and a number of primary publications, with the thesis itself being a “review paper” that brings it all together.

By the way, sometimes the word “dissertation” is used instead of “thesis.” For example, at some U.S. universities, one speaks of a master’s thesis but a doctoral dissertation. Whatever term one uses, the principles are much the same for preparing the less extensive master’s-level document and the more extensive doctoral one.

2. TIPS ON WRITING

Few rules exist for writing a thesis, except those that may prevail in your own institution. Check whether your institution has a thesis manual or other set of instructions. If it does, obtain it and follow it carefully. Otherwise, your graduation may be delayed because of failure to use the required thesis format. If you do not have rules to follow, or even if you do, go to your departmental library— or, increasingly, your institutional library’s online collection of theses—and examine the theses submitted by previous graduates of the department, especially those who have gone on to fame and fortune. Perhaps you will be able to detect a common flavor. Whatever ploys worked in the past for others are likely to work for you now.

Theses typically consist of several chapters. Sometimes the chapters correspond to the parts of an IMRAD scientific paper: introduction, methods, results, and discussion. Or, if a thesis reports a number of studies, the central part may include a chapter about each study. As noted, sometimes a thesis consists mainly of a set of published papers. In addition to chapters, common components of theses include a title page, acknowledgments, an abstract, a table of contents, a list of figures and tables, a list of abbreviations, and appendixes.

A thesis also should contain a substantial reference list, helping to demonstrate your familiarity with the literature in your field. In this regard, a thesis can resemble a review paper. Indeed, the introduction or a separate literature- review chapter generally should present a thorough review of previous work to which yours is related. Further, it is often desirable to go back into the history of your subject. You might thus compile a really valuable review of the literature of your field, while at the same time learning something about the history of science, which could turn out to be a most valuable part of your education.

Start with and work from carefully prepared outlines. Be careful about what goes in what section. If you have one or several results sections, the content must be your results, not a mixture of your results with those of others. If you need to present results of others, to show how they confirm or contrast with your own, you should do this within a discussion section. Otherwise, confusion may result, or, worse, you could be charged with lifting data from the published literature.

Give special attention to the introduction in your thesis for two reasons. First, for your own benefit, you need to clarify what problem you attacked, how and why you chose that problem, how you attacked it, and what you learned during your studies. The rest of the thesis should then flow easily and logically from the introduction. Second, first impressions are important, and you would not want to lose your readers in a cloud of obfuscation right at the outset.

Writing a thesis is a good chance to develop your skill in scientific writing. If a committee of faculty members is supervising your thesis research, seek feedback on one or more drafts of your thesis from committee members, especially the committee chair. (If you can choose the committee members, try to include someone who writes very well and is willing to help others with writing.) Seek feedback early from the committee chair and others, to help prevent the need for extensive revisions at the end.

Universities keep copies of theses so that those interested can read them. Increasingly, they have been requiring electronic copies for this purpose. Use of electronic rather than paper copies saves space in libraries; can make theses easier for readers to obtain; and can let you include materials, such as videos or animations, that are difficult or impossible to provide in a bound thesis. Be sure to find out whether your institution requires you to submit your thesis electronically and, if so, what the instructions are.

3. WHEN TO WRITE THE THESIS

You would be wise to begin writing your thesis long before it is due. In fact, when a particular set of experiments or some major facet of your work has been completed, you should write it up while it is still fresh in your mind. If you save everything until the end, you may find that you have forgotten important details. Worse, you may find that you lack time to do a proper writing job. If you have not done much writing before, you might be amazed at what a painful and time-consuming process it is. You are likely to need a total of three months to write the thesis, on a relatively full-time basis. You will not have full time, however, nor can you count on the ready availability of your thesis advisor. Allow at least 6 months.

As implied in the preceding paragraph, a thesis need not be written from beginning to end. Work on the literature review section generally should start early, because your research should be based on previous research. Regardless

of whether you do laboratory research or other investigation (such as field research or social-science surveys), you should draft descriptions of methods soon after methods are used, while memory is still complete. Often, the introduction is best drafted after the sections presenting and discussing the results, so the introduction can effectively prepare readers for what will follow.

Of course, ideas for any part of your thesis may occur to you at any time. Early in your research, consider establishing a physical or electronic file for each part of your thesis. Any time ideas occur to you for the thesis, put the ideas in the appropriate file. Similarly, if you come across readings that might be relevant to a given section, include or mention them in the file. Such files help keep you from losing ideas and materials that could contribute to your thesis. They also give you content to consider using as you begin drafting each section.

Perhaps you noticed that we said “drafting,” not “writing.” Much to the surprise of some graduate students, a good thesis is likely to require multiple drafts. Some graduate students think that once the last word leaves the keyboard, the thesis is ready to turn in. However, as with journal articles, considerable revision commonly is needed for the thesis to achieve its potential. Indeed, using feedback from one’s graduate committee to strengthen the content, organization, and wording of one’s thesis can be an important part of one’s graduate education. Be prepared to need more time than expected to put your thesis in final form. Both in terms of the quality of the product and in terms of learning obtained that can aid in your future writing, the time is likely to be well spent.

4. RELATIONSHIP TO THE OUTSIDE WORLD

Remember, your thesis will bear only your name. Theses are normally copyrighted in the name of the author. The quality of your thesis and of any related publications in the primary literature probably will affect your early reputation and your job prospects. A tightly written, coherent thesis will get you off to a good start. An overblown encyclopedia of minutiae will do you no credit. The writers of good theses try hard to avoid the verbose, the tedious, and the trivial.

Be particularly careful in writing the abstract of your thesis. The abstracts of doctoral dissertations from many institutions are published in Dissertation Abstracts International, thus being made available to the larger scientific community.

Writing a thesis is not a hurdle to overcome before starting your scientific career. Rather, it is a beginning step in your career and a foundation for your later writing. Prepare your thesis carefully, and use the experience as a chance to refine your writing skills. The resulting document and abilities will then serve you well.

5. FROM THESIS TO PUBLICATION

People sometimes speak of “publishing a thesis.” However, theses themselves are rarely, if ever, publishable. One reason is that theses commonly are intended partly to show that the graduate student has amassed considerable knowledge, and so they tend to contain much material that helps demonstrate scholarship but would not interest readers. Extracting one or more publications from a thesis generally entails considerable trimming and condensation. More specifically, writing one or more scientific papers based on a thesis requires determining what in a thesis is new and of interest to others and then presenting it in appropriate format and at an appropriate level of detail. In fields in which books present new scholarship, converting a dissertation to a book (Germano 2013) often includes decreasing the manuscript to a marketable length, dividing it into more chapters, using fewer quotations and examples, and otherwise making the manuscript more readable, cohesive, and engaging.

When you finish your thesis, promptly prepare and submit any manuscripts based on it, if you have not yet done so. Do so even if you are tired of your thesis topic—and tired from writing and defending a thesis. The longer you wait, the harder it is to return to your thesis and prepare a suitable manuscript based on it. And importantly, having one or more thesis-based writings published or in press can help catapult you into the next stage of your career.

Source: Gastel Barbara, Day Robert A. (2016), How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, Greenwood; 8th edition.

Its fantastic as your other posts : D, appreciate it for putting up. “The squeaking wheel doesn’t always get the grease. Sometimes it gets replaced.” by Vic Gold.

I do not even know how I finished up here, but I assumed this submit used to be good. I do not realize who you’re however certainly you’re going to a famous blogger when you aren’t already 😉 Cheers!