1. ETHICS AS A FOUNDATION

Before writing a scientific paper and submitting it to a journal—and indeed, before embarking on your research—you should know the basic ethical norms for scientific conduct and scientific publishing. Some of these norms may be obvious, others not. Therefore, a basic overview is provided below. Graduate students and others seeking further information on ethics in scientific publishing and more broadly in science may do well to consult On Being a Scientist: Responsible Conduct in Research (Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy 2009), which contains both guidance and case studies and is accompanied online by a video. Other resources include ethics chapters in style manuals in the sciences.

2. AUTHENTICITY AND ACCURACY

That research reported in a journal should actually have been done may seem too obvious to mention. Yet cases exist in which the author simply made up data in a paper, without ever doing the research. Clearly, such “dry-labbing,” or fabrication, is unethical. Fiction can be a grand pursuit, but it has no place in a scientific paper.

More subtle, and probably more common, are lesser or less definite deviations from accuracy: omitting outlying points from the data reported, preparing figures in ways that accentuate the findings misleadingly, or doing other tweaking. Where to draw the line between editing and distortion may not always be apparent. If in doubt, seek guidance from a more experienced scientist in your field—perhaps one who edits a journal.

The advent of digital imaging has given unethical researchers new ways to falsify findings. (Journal editors, though, have procedures to detect cases in which such falsification of images seems probable.) And ethical researchers may rightly wonder what manipulations of digital images are and are not valid. Sources of guidance in this regard include recent sets of guidelines for use and manipulation of scientific digital images (Cromey 2010, 2012).

For research that includes statistical analysis, reporting accurately includes using appropriate statistical procedures, not those that may distort the findings. If in doubt, obtain the collaboration of a statistician. Enlist the statistician early, while still planning the research, to help ensure that you collect appropriate data. Otherwise, ethical problems may include wasting resources and time. In the words of R.A. Fisher (1938), “To consult the statistician after an experiment is finished is often merely to ask him to conduct a post mortem examination.”

3. ORIGINALITY

As discussed in the previous chapter, the findings in a scientific paper must be new. Except in rare and highly specialized circumstances, they cannot have appeared elsewhere in the primary literature. In the few instances in which republication of data may be acceptable—for example, in a more extensive case series or if a paper is republished in another language—the original article must be clearly cited, lest readers erroneously conclude that the old observations are new. To republish a paper (either in another language or for readers in another field) permission normally must be obtained from the journal that originally published the paper.

Beginning scientists sometimes wonder whether they may submit the same manuscript to two or more journals simultaneously. After all, a candidate can apply to several graduate programs at once and then choose among those offering acceptance. An analogous situation does not hold for scientific papers. Simultaneous submission wastes resources and is considered unethical. Therefore, begin by submitting your paper only to your first-choice journal. If that journal does not accept your paper, you can then proceed to the next journal on your list.

Originality also means avoiding “salami science” (or, for vegetarians, “cucumber science”)—that is, thinly slicing the findings of a research project, as one might slice a sausage or cuke, in order to publish several papers instead of one (or, in the case of a large research project, many papers instead of a few). Good scientists respect the integrity of their research and do not divide it excessively for publication. Likewise, good hiring committees and promotion committees look at the content of publications, rather than only the number, and so are not fooled by salami science.

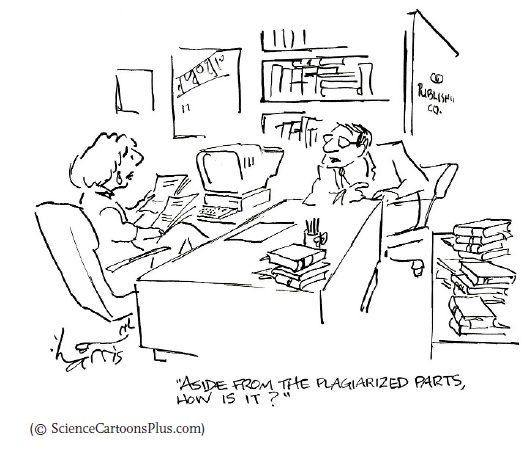

4. CREDIT

Good scientists build on each other’s work. They do not, however, take credit for others’ work.

If your paper includes information or ideas that are not your own, be sure to cite the source. Likewise, if you use others’ wording, remember to place it in quotation marks (or to indent it, if the quoted material is long) and to provide a reference. Otherwise, you will be guilty of plagiarism, which the U.S. National Institutes of Health defines as “the appropriation of another person’s ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit” (National Institutes of Health 2010). To avoid inadvertent plagiarism, be sure to include information about the source when you copy or download materials others have written. To avoid the temptation to use others’ wording excessively, consider drafting paragraphs without looking directly at the source materials; then look at the materials to check for accuracy.

In journal articles in most fields of science, it is unusual to include quotations from others’ work. Rather, authors paraphrase what others have said. Doing so entails truly presenting the ideas in one’s own way; changing a word or two does not constitute paraphrasing. On rare occasions—for example, when an author has phrased a concept extraordinarily well—quoting the author’s own phrasing may be justified. If you are unsure whether to place in quotation marks a series of words from a publication, do so. If the quotation marks are unnecessary, an editor at the journal can easily remove them. If, however, they are missing but should have been included, the editor might not discover that fact (until, perhaps, a reader later does), or the editor might suspect the fact and send you an inquiry that requires a time-consuming search. Be cautious, and thus save yourself from embarrassment or extra work.

Resources to educate oneself about plagiarism, and thus learn better how to avoid it, include a tutorial from Indiana University (Frick and others 2016), an online guide to ethical writing (Roig 2003), and a variety of materials posted on websites of university writing centers. Another resource to consider is plagiarism-checking software. Such software helps identify passages of writing that seem suspiciously similar to text elsewhere; one can then see whether it does indeed appear to be plagiarized. Such software, such as Turnitin, is available at many academic institutions. Free plagiarism checkers, seemingly of varied quality, also exist. Many journal publishers screen submissions with plagiarism checking software, such as CrossCheck. Consider pre-screening your work yourself to detect and remove inadvertent plagiarism.

Also be sure to list as an author of your paper everyone who qualifies for authorship. (See Chapter 8 for more in this regard.) Remember as well to include in the acknowledgments those sources of help or other support that should be listed (see Chapter 14).

5. ETHICAL TREATMENT OF HUMANS AND ANIMALS

If your research involves human subjects or animals, the journal to which you submit your paper is likely to require documentation that they were treated ethically. Before beginning your study, obtain all needed permissions with regard to human or animal research. (In the United States, doing so entails having your research protocol reviewed by a designated committee at your institution.)

Then, in your paper, provide the needed statement(s) in this regard. For guidance, see the instructions to authors for the journal to which you are submitting your paper, and use as models papers similar to yours that have appeared in the journal. You may also find it useful to consult relevant sections of style manuals in the sciences. If in doubt, check with the publication office of the journal.

6. DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors of scientific papers sometimes have conflicts of interest—that is, outside involvements that could, at least in theory, interfere with their objectivity in the research being reported. For example, they may own stock in the company making the product being studied, or they may be consultants to such a company.

Increasingly, it seems, journals are requiring authors to report such conflicts of interest. Some have checklists for doing so, and others ask more generally for disclosure. Journals vary in the degree to which they note conflicts of interest along with published papers (Clark 2005).

Ethics requires honest reporting of conflicts of interest. More importantly, ethics demands that such involvements not interfere with the objectivity of your research. Some scientists avoid all such involvements to prevent even the possibility of seeming biased.

Source: Gastel Barbara, Day Robert A. (2016), How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, Greenwood; 8th edition.

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after checking through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyhow, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be bookmarking and checking back often!

I was reading through some of your content on this internet site and I conceive this website is very informative ! Keep on posting.