1. THE LABOUR-CAPITAL PARTNERSHIP

Sections 4 and 5 have been concerned with the difficulties faced by cooperative and profit-sharing enterprises when confronting investment and employment decisions. The labour-capital partnership is a form of organisation which has some attractive theoretical properties and is discussed in detail by Meade (1989). It is distinguished from the worker cooperative in having outside holders of shares. It is distinguished from Weitzman’s profitsharing enterprise in that workers are issued with labour share certificates. The raising of more capital would require the issue of more capital share certificates, while the recruitment of more labour would involve granting the new workers extra labour share certificates. All share certificates would entitle the holder to the same dividend. In Meade’s presentation, equal numbers of Board members are elected by the group of capital shareholders and the group of labour shareholders respectively.

Because capital share certificates are freely tradable, the time-horizon problem associated with pure worker cooperatives and labour-managed firms is circumvented. Any capital project which adds to the total distributable surplus more than is required to pay the dividend on the new capital share certificates, will be approved by all existing holders of capital and labour share certificates. Similarly, any extra worker who raises the distributable surplus by more than is required to pay the dividend on his or her labour share certificates will be unanimously approved. Tension between capital and labour over investment plans and team size is thereby reduced.

The ‘perverse supply response’ of the labour-managed firm in Figure 10.4(a) is also overcome. A rise in the price of the firm’s product will not lead to a reduction of employment because existing employee-sharers have labour share certificates which entitle them to a dividend whether or not the firm makes use of their services. In other words, the firm cannot simply fire workers and reduce its size. Members have rights to a share in the residual, providing they are available for work. There would still be resistance to increasing the size of the team in the face of temporary price rises, however, because this would leave it too large in the long run. Since the employment of newcomers involves long-run commitments, the number of worker- sharers would be determined by long-run considerations. Greater short-run flexibility would require the firm to employ some people on short-term wage contracts, thus introducing two classes of worker.14

Favourable conditions which are not transitory will imply that new workers will require to be issued with fewer labour share certificates (since the expected dividends on all shares are higher). Existing labour shareholders therefore do not have to give up a portion of the reward from past successes to newcomers and will be more inclined to accept them. All workers receive the same dividend on their certificates, but the number of certificates they hold will depend on when they joined the firm. This is why Meade refers to firms structured in this way as discriminating labour-capital partnerships. Some of the return on the certificates of older workers may therefore be seen as reflecting the build-up over time of their firm-specific human capital, a reward for participating in the development of a successful ‘architecture’, and a return to entrepreneurship. It is possible to imagine a portion of a worker’s labour share certificates being converted over time into capital share certificates in recognition of this process. However, if firm-specific human capital were represented by a tradable capital share certificate, the worker embodying that human capital would no longer be firm dependent. He or she could, without penalty, leave the firm for a job elsewhere and sell the capital share certificates on the capital market. In other words, this policy might lead to the dissipation of the specific human capital in the firm unless workers converting labour into capital share certificates could bind themselves not to leave the team.15

Retirement of workers presents another difficulty for the labour-capital partnership. If the retiring worker’s certificates are simply cancelled and new ones issued sufficient to attract a replacement, then to the extent that this procedure implies a net reduction in the outstanding shares, all continuing shareholders (both labour and capital) will benefit from the worker’s retirement. In this way, the gains from any long-term profit opportunities discovered by workers ‘leak away’ to capital shareholders. This seepage could be prevented if the retirees were permitted to keep any share certificates in excess of those required to attract a replacement worker. The danger here is that the pure profits accruing to the firm at the time of a worker’s retirement might turn out to be transitory. When the pure profits disappear, the distributable surplus of the team will fall and replacement workers will leave the firm unless they are issued with further labour share certificates to raise their incomes to the levels achievable in alternative positions. Thus, the total of outstanding shares increases and the providers of risk capital will find their capital share certificates ‘diluted’. A further possibility is that any excess certificates available at the time of a worker’s retirement could be redistributed to the rest of the labour force. This, however, would introduce an incentive to restrict the size of the team on the part of existing workers. In this way they would hope to gain more from the redistributed labour share certificates of retirees.16

The labour-capital partnership has theoretical properties which overcome some of the problems associated with worker cooperatives. It is a form of governance that, in principle, protects firm-specific human capital while permitting the use of outside financial capital with its risk-spreading advantages. The interests of capital and labour shareholders are cleverly aligned over such matters as employment and investment policy. Labour participates in the risk of the enterprise although the risk of unemployment is lower than in an investor-owned firm, while the risk of very low income is limited by the ability to move elsewhere.

On the other hand, any attempt to operate such an enterprise in practice would face some obvious difficulties. Investment, for example, must be financed by the issue of new capital share certificates and not from internally generated funds. The accounting problems of estimating the distributable surplus making allowances for the depreciation of capital and corrections for inflation are substantial. In an investor-owned firm, accounting conventions may be important for conveying a true impression of the state of the business, but the application of different conventions would not directly affect the position of labour or the underlying value of shareholders’ claims.

Further, the ability of managers to discipline workers (and vice versa) in an environment of a high level of employment security and widely held residual claims is an open question. Hierarchical incentive devices such as those discussed in Chapter 6 are logically feasible (promotion would bring with it the issue of extra labour share certificates). In the absence of the takeover and of monitoring by outside capital shareholders, motivation of senior managers might require the issue of special bonus shares for good overall performance. The managerial labour market would also be a possible motivator because successful management would be communicated through the prices of the traded capital share certificates. ‘Inside’ worker- directors on the Board would be expected to offer some monitoring services, since they are likely to be well informed and have a significant personal interest in the distributable surplus. The closest monitoring of managers will be to no avail, however, if the managers have no mechanism for motivating workers. As already mentioned, a tournament structure might provide some leverage, even where the threat of termination is not significant, but an additional factor yet to be discussed is the role of peergroup pressure.

2. THE ROLE OF PEER PRESSURE

With purely self-interested behaviour on the part of team members, effort is expected to decline as the residual is shared amongst an increasingly large number of people. Each person’s private calculation is to equate the additional costs of effort with the private payoff. If the residual is shared equally, the private payoff will be 1/Nth of the payoff to the team as a whole where N is the size of the team. Where effort cannot be easily observed, measured and rewarded, therefore, the effectiveness of profit sharing as a means of providing alternative incentives will be severely limited by the free-rider problem. This is the conventional reasoning and it is the basic problem which permeates the entire theory of economic organisation.

2.1. Internal Pressure

Suppose, however, that people are capable of experiencing some disutility from a consciousness of having not performed well in a team endeavour. The first and simplest situation might be to assume that, even if their peers did not observe their shirking, free riders would experience some feelings of guilt. Guilt is unobserved or ‘internal’ pressure. Now, it could be argued that to assume the existence of ‘internal’ pressure or guilt is effectively to assume away the problem of economic organisation. Clearly, if everyone felt a strong social motivation not to shirk in any team activity or defect in any prisoner’s dilemma, the world would be a much less interesting place. The assumption of a pervasive sense of guilt has seemed unreasonable to most observers of the social scene throughout the centuries. As Thackeray put it, ‘We grieve at being found out, and at the idea of shame or punishment; but the mere sense of wrong makes very few people unhappy in Vanity Fair’.17

We may, however, accept Thackeray’s tolerant realism without denying the existence of guilt in its entirety. Some down-to-earth observations of

Vanity Fair suggest that institutions exist which rely heavily on inculcating a sense of commitment to collective goals amongst their members. The most obvious example is that of military institutions, which invest heavily in building ‘team spirit’ and inculcating loyalty to the unit. Military units rely for their effectiveness on people behaving cooperatively, even in dangerous circumstances where they cannot be observed and where the incentive to defect would be compelling for most ‘untrained’ people. Assuming that human beings have the capacity to respond to some ‘social conditioning’, ‘indoctrination’ or whatever we choose to call investments in the generation of group loyalty, further questions of economic significance are suggested. Under what conditions will such investments be productive and where might they be expected to fail?

Investing resources in making workers feel loyalty to the shareholders of a joint-stock company would probably be considered by most people a waste of effort. For loyalty-building investments to be productive, the wellbeing of each member of the group must be mutually dependent, the activities of each member should be costly to monitor, and the group should be small and homogeneous enough for people to ‘empathise’ with the predicament of their colleagues.18 If the actions of individuals in a group have no effect on the utility of other members, no guilt can accompany lack of effort. If actions can be monitored at very low cost, loyalty is unnecessary to achieve effort. If the return to loyalty building is low in the absence of natural ‘empathy’ then we would not expect to observe large investments in team spirit in heterogeneous groups. These factors are consistent with strong family or social links between partners, and with a greater investment in loyalty building where profits are shared than where they are not.

2.2. External Pressure

Guilt or ‘internal’ pressure is a valuable resource because it operates even in the absence of observability. Shame or ‘external’ pressure, requires that a person’s actions are observable by his or her peers. Although the observability requirement restricts the range of circumstances in which shame can be effective, the pressure which it can exert when conditions are suitable is enormous. Adam Smith, in the Theory of Moral Sentiments, asks to what we can attribute all the ‘toil and bustle’ of the world. It cannot, he argues, merely be a desire to satisfy the basic needs of hunger or shelter. For people who have satisfied these basic requirements of existence the benefits of action are more social. ‘To be observed, to be attended to, to be taken notice of with sympathy, complacency and approbation, are all the advantages which we can propose to derive from it. It is the vanity, not the ease, or the pleasure, which interests us.’19 If Adam Smith is correct here in his assessment of human motivations, the potential (both productive and unproductive) of the crushing force of social disapproval as a means of inducing effort and compliance with group norms should not be overlooked.

For shame to be an effective motivator, actions must be observed. If peers are to monitor one another, there must be some payoff for doing so. Profit sharing is therefore a necessary condition for peer-group monitoring. If I am a wage earner and my colleagues’ activities do not affect me, I will have no incentive to monitor them. Where their effort affects the size of my share in the team’s residual, then an incentive will exist. As with the theory of Chapter 6, there must also be a penalty associated with being discovered shirking, which we may here envisage as social isolation and a sense of shame rather than a specific monetary penalty. We should also note once more that an ability costlessly to escape censure by leaving the group would be to remove the power of the group to inflict punishment. Some form of dependency is required even in profit-sharing groups and communities formed for collective purposes.20

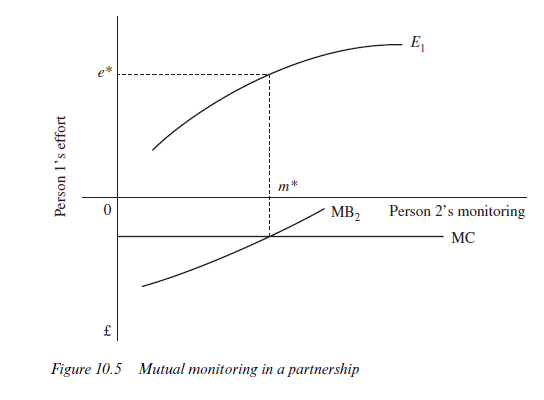

With two identical profit sharers, the determination of the amount of monitoring and effort for each person is shown schematically in Figure 10.5. The figure is a much-simplified formulation of the arguments presented in Kandel and Lazear (1992).

The effort of Person 1 increases with the monitoring of person 2 (curve Ej). We assume that extra monitoring increases the accuracy of observation. Greater work effort will be more effective at reducing peer pressure when observation is accurate than when it is inaccurate. Thus, person 1 will find it worthwhile to increase his or her effort in response to greater monitoring by person 2. Assuming that monitoring is not entirely costless, person 2 will monitor only to the point at which his or her private gains from person l’s extra effort (in this case one half of the additional output) equal the extra monitoring costs incurred (MC). With diminishing returns to effort, person 2’s marginal benefit from person l’s extra effort is given by curve MB2. In the context of identical individuals, both will monitor with intensity m* and work with intensity e*.

What happens as the number of people in the group increases? Up to a point, we might expect peer pressure to rise. Ten hostile or otherwise disapproving erstwhile colleagues might be worse than just a single one. Presumably, there are limits to this tendency, however, as relationships become more distant and detached as numbers rise above a certain point. Similarly, the incentive to monitor may rise over a certain range. Supposing that a given degree of monitoring intensity is as effective when spread over ten people as it is when applied to a single person (monitoring has public good characteristics for groups below a certain size) the private benefits from monitoring will increase. Again, however, there must be some limit. Presumably a person cannot monitor one hundred or one thousand people as easily as five or ten. A person’s monitoring may be a form of ‘joint input’, but it will become subject to diminishing effectiveness after a certain point.

For relatively small groups, therefore, peer pressure deriving from mutual monitoring may be an important component of a satisfactory theory of profit sharing. It is even conceivable that the peer pressure generated may be substantial enough to result in a greater level of effort than the contractors would ideally prefer. Just as we saw in Chapter 6 that the wrong structure of prizes in a tournament could result in ‘too great’ a level of effort, an environment with excessive peer pressure might logically produce a similar effect. For very large groups, however, such an outcome would seem unlikely. A person will not monitor those in his or her peer group if the benefits flow away to people outside, while punishing people who are not cooperative is likely to become less certain as the size and complexity of the group rises.21

Peer pressure will be most effective when the size of the group is such that each individual can effectively monitor all the others. Further, monitoring will be more effective when each person has a good knowledge of the nature of the work they are observing and the skills required to do it effectively. This is another reason for expecting successful profit-sharing groups to be small and relatively homogeneous. As was noted earlier, Hansmann (1990) highlights the adverse effect on the costs of collective decision making of group diversity because of conflicts of interest. In contrast, Kandel and Lazear (1992) draw attention to the adverse consequences for the effectiveness of peer-group monitoring of heterogeneity amongst the profit sharers and hence of a low degree of observational accuracy. ‘The grouping of partners by occupation is a direct implication of the mutual monitoring analysis … Partnerships should be less prevalent in firms in which workers specialise in non-overlapping tasks’ (p. 814).

Our discussion of the implications of various forms of profit sharing between workers, or between the workers and providers of finance in an enterprise, is now complete. As mentioned in section 1, however, there are occasions when consumers find it advantageous to band together to form a cooperative. Before leaving the subject of profit sharing, therefore, section 8 investigates the rationale and governance structure of the retail cooperative.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found It positively useful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & help other users like its aided me. Good job.