Clearly there are gains from international trade in an exchange economy. We have seen that two persons or two countries can benefit by trading to reach a point on the contract curve. However, there are additional gains from trade when the economies of two countries differ so that one country has a comparative advantage in producing one good while the other has a comparative advantage in producing another.

1. Comparative Advantage

Country 1 has a comparative advantage over Country 2 in producing a good if the cost of producing that good, relative to the cost of producing other goods in 1, is lower than the cost of producing the good in 2, relative to the cost of producing other goods in 2.5 Note that comparative advantage is not the same as absolute advantage. A country has an absolute advantage in producing a good if its cost is lower than the cost in another country. A comparative advantage, on the other hand, implies that a country’s cost, relative to the costs of other goods it produces, is lower than the other country’s.

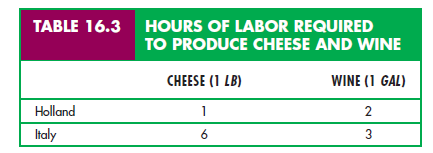

When each of two countries has a comparative advantage, they are better off producing what they are best at and purchasing the rest. To see this, suppose that the first country, Holland, has an absolute advantage in producing both cheese and wine. A worker there can produce a pound of cheese in 1 hour and a gallon of wine in 2 hours. In Italy, on the other hand, it takes a worker 6 hours to produce a pound of cheese and 3 hours to produce a gallon of wine. The production relationships are summarized in Table 16.3.

Holland has a comparative advantage over Italy in producing cheese. Holland’s cost of cheese production (in terms of hours of labor used) is half its cost of producing wine, whereas Italy’s cost of producing cheese is twice its cost of producing wine. Likewise, Italy has a comparative advantage in producing wine, which it can produce at half the cost at which it can produce cheese.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN NATIONS TRADE The comparative advantage of each country determines what happens when they trade. The outcome will depend on the price of each good relative to the other when trade occurs. To see how this might work, suppose that with trade, one gallon of wine sells for the same price as one pound of cheese in both Holland and Italy. Suppose also that because there is full employment in both countries, the only way to increase production of wine is to take labor out of the production of cheese, and vice versa.

Without trade, Holland could, with 24 hours of labor input, produce 24 pounds of cheese, 12 gallons of wine, or a combination of the two, such as 18 pounds of cheese and 3 gallons of wine. But Holland can do better. For every hour of labor, Holland can produce 1 pound of cheese, which it can trade for 1 gallon of wine; if the wine were produced at home, 2 hours of labor would be required. It is, therefore, in Holland’s interest to specialize in the production of cheese, which it will export to Italy in exchange for wine. If, for example, Holland produced 24 pounds of cheese and traded 6, it would be able to consume 18 pounds of cheese and 6 gallons of wine—a definite improvement over the 18 pounds of cheese and 3 gallons of wine available in the absence of trade.

Italy is also better off with trade. Note that without trade, Italy can, with the same 24 hours of labor input, produce 4 pounds of cheese, 8 gallons of wine, or a combination of the two, such as 3 pounds of cheese and 2 gallons of wine. On the other hand, with every hour of labor, Italy can produce one-third of a gallon of wine, which it can trade for one-third of a pound of cheese. If it produced cheese at home, twice as much time would be involved. Specialization in wine production, therefore, is advantageous for Italy. Suppose that Italy produced 8 gallons of wine and traded 6; in that case, it would be able to consume 6 pounds of cheese and 2 gallons of wine—likewise an improvement over the 3 pounds of cheese and 2 gallons of wine available without trade.

2. An Expanded Production Possibilities Frontier

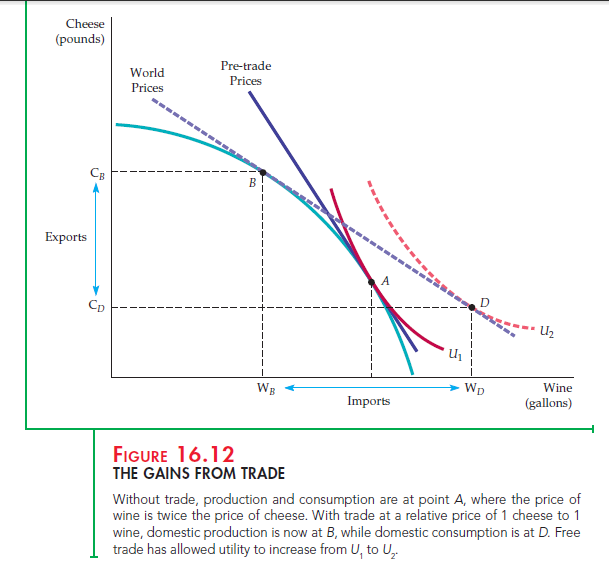

When there is comparative advantage, international trade has the effect of allowing a country to consume outside its production possibilities frontier. This can be seen graphically in Figure 16.12, which shows a production possibilities frontier for Holland. Suppose initially that Holland has been prevented from trading with Italy because of a protectionist trade barrier. What is the outcome of the competitive process in Holland? Production is at point A, on indifference curve U1, where the MRT and the pre-trade price of wine is twice the price of cheese. If Holland were able to trade, it would want to export 2 pounds of cheese in exchange for 1 gallon of wine.

Suppose now that the trade barrier is dropped and Holland and Italy are both open to trade. Suppose also that, as a result of differences in demand and costs in the two countries, trade occurs on a one-to-one basis. Holland will find it advantageous to produce at point B, the point of tangency of the 1/1 price line and Holland’s production possibilities frontier.

That is not the end of the story, however. Point B represents the production decision in Holland. (Once the trade barrier has been removed, Holland will produce less wine and more cheese domestically.) With trade, however, consumption will occur at point D, at which the higher indifference curve U2 is tangent to the trade price line. Thus trade has the effect of expanding Holland’s consumption choices beyond its production possibilities frontier. Holland will import WD — WB units of wine and export CB – CD units of cheese.

With trade, each country will undergo a number of important adjustments. As Holland imports wine, the production of domestic wine will fall, as will employment in the wine industry. Cheese production will increase, however, as will the number of jobs in that industry. Workers with job-specific skills may find it difficult to change employment. Not everyone will, therefore, gain as the result of free trade. Although consumers will clearly be better off, producers of wine and workers in the wine industry are likely to be worse off, at least temporarily.

Source: Pindyck Robert, Rubinfeld Daniel (2012), Microeconomics, Pearson, 8th edition.

Great post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely helpful information particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info a lot. I was seeking this certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.