1. THE COPYEDITING AND PROOFING PROCESSES

The following is a brief description of the process that your manuscript follows after it has been accepted for publication.

The manuscript usually goes through a copyediting procedure during which errors in spelling and grammar are corrected. In addition, the copy editor will standardize all abbreviations, units of measure, punctuation, and spelling in accord with the style of the journal in which your manuscript is to be published. At some journals, copy editors also revise writing to increase readability, for example by improving sentence structure and making wording more concise. Many English-language journals with sufficient staff to do so devote extra effort to copyediting papers by non-native speakers of English, in order to promote clear international communication. The copy editor may direct questions to you if any of your wording is not clear or if any additional information is needed. These questions may appear as author queries written on or accompanying the proofs (copies of typeset material) sent to the author. Alternatively, the queries may appear on or with the copyedited manuscript, if the journal sends it to the author for approval before preparing the proof.

Typically, the edited version of the electronic file that you provided is loaded into a computer system that can communicate with a typesetting system, which will produce the proofs of your article. The copy editor or compositor keyboards codes that indicate the typefaces and page layout.

The output of this effort is your set of proofs, which is then returned to you so that you may check the editorial work that has been done on your article, check for typographical errors, and answer any questions by the copy editor. Commonly, you will receive the proof of your article as a PDF file.

Finally, someone at the journal will keyboard the corrections that you make on your proofs. The final version will become the type that you see on the pages of the journal.

2. WHY PROOFS ARE SENT TO AUTHORS

Some authors seem to forget their manuscripts as soon as they are accepted for publication, paying little attention to the proofs when they arrive and assuming that their papers will magically appear in the journals, without error.

Why are proofs sent to authors? Authors are provided with proofs of their papers for one main reason: to check the accuracy of the type composition. In other words, you should examine the proofs carefully for typographical errors. Even if you carefully proofread and spell-checked your paper before submitting it, errors can remain or can occur when editorial changes are input. And sometimes the typesetting process mysteriously converts Greek letters into squiggles, cuts off lines of text, or causes other mischief. No matter how perfect your manuscript might be, it is only the printed version in the journal that counts. If the printed article contains serious errors, all kinds of 1 ater problems can develop, not the least of which may be serious damage to your reputation.

The damage can be real in that many errors can destroy comprehension. Something as minor as a misplaced decimal point can sometimes make a published paper almost useless. In this world, we can be sure of only three things: death, taxes, and typographical errors.

3. MISSPELLED WORDS

Even if the error does not greatly affect comprehension, it won’t do your reputation much good if it turns out to be funny. Readers will know what you mean if your paper refers to a “nosocomical infection,” and they will get a laugh out of it, but you won’t think it is funny.

A major laboratory-supply corporation submitted an ad with a huge boldface headline proclaiming that “Quality is consistant because we care.” We certainly hope they cared more about the quality of their products than they did about the quality of their spelling.

Although all of us in publishing occasionally lose sleep worrying about typographical errors, we can take comfort in the realization that whatever slips by our eye is probably less grievous than some of the monumental errors committed by our publishing predecessors.

An all-time favorite error occurred in a Bible published in England in 1631. The Seventh Commandment read: “Thou shalt commit adultery.” We understand that Christianity became very popular indeed after publication of that edition. If that statement seems blasphemous, we need only refer you to another edition of the Bible, printed in 1653, in which appears the line: “Know ye that the unrighteous shall inherit the kingdom of God.”

If you read proofs in the same way and at the same speed that you ordinarily read scientific papers, you will probably miss 90 percent of the typographical errors.

The best way to read proofs is, first, read them and, second, study them. The reading will miss 90 percent of the errors, but it will catch errors of omission. If the printer has dropped a line, reading for comprehension is the only likely way to catch it. Alternatively, or additionally, it can be helpful for two people to read the proof, one reading aloud while the other follows the manuscript.

To catch most errors, however, you must slowly examine each word. If you let your eye jump from one group of words to the next, as it does in normal reading, you will not catch very many misspellings. Especially, you should study the technical terms. A good keyboarder might be able to type the word “cherry” 100 times without error; however, there was a proof in which the word “Escherichia” was misspelled 21 consecutive times (in four different ways). One might also wonder about the possible uses for a chemical whose formula was printed as C12H6Q3. One way to look at each word without distraction is to read the proof backward, from last word to first.

As a safeguard, consider having someone else review the proof, in addition to doing so yourself. But do not delegate the proofreading solely to others, lest you suffer the plight of a colleague of ours who, tired of the publication process, had an office worker review the proof. Only after the journal was published did the colleague find that the article title contained a misspelling.

We mentioned the havoc that could occur from a misplaced decimal point. This observation leads to a general rule in proofreading. Examine each and every number carefully. Be especially careful in proofing the tables. This rule is important for two reasons. First, errors frequently occur in keyboarding numbers, especially in tabular material. Second, you are the only person who can catch such errors. Most spelling errors are caught in the printer’s proof room or in the journal’s editorial office. However, professional proofreaders catch errors by “eyeballing” the proofs; the proofreader has no way of knowing that a “16” should be a “61.”

4. MARKING THE CORRECTIONS

Like much else in scientific publishing, correction of proofs has been changing in the electronic era. No longer do authors receive galley proofs (long strips of type) to correct before page proofs are prepared. And rather than being sent proofs by mail, authors receive them electronically or access them through websites. Accordingly, procedures for indicating corrections have been evolving. Be sure to follow the current instructions that the journal provides with the proof.

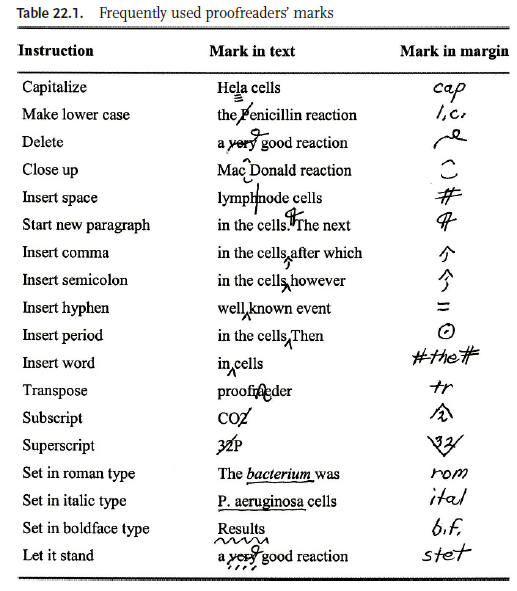

The long-established procedure is to mark each error twice on a hard copy of a proof, once at the point where it occurs and once in the margin opposite where it occurs. The compositor uses the margin marks to find the errors, as a correction indicated only in the body of the text can easily go unnoticed. Standard proofreading marks, the most common of which are listed in Table 22.1, should be used to indicate corrections. Normally, if you are to print out a hard copy and indicate corrections on it, the publisher provides a list of such marks along with the proof. Learning the main such marks can facilitate reviewing the proofs of your papers and aids in proofing typeset versions of other items you write.

Other options have been developing. Some journals, for example, ask authors to use tools in Adobe Acrobat to indicate corrections on PDF versions of the proof. Some have their own online proofreading systems for authors to use.

Whatever approach is used, return the proofs quickly, by the deadline from the journal. Failure to do so disrupts the publication schedule of the journal and can result in delay or even withdrawal of your paper. If you think you might be unreachable when the proofs become available, inform the journal, so the timetable can be revised or the proofs can be sent to a coauthor or other colleague to review.

5. ADDITIONS TO THE PROOFS

Early in this chapter, we stated that authors are sent proofs so that they can check the accuracy of the typesetting. Stated negatively, the proof stage is not the time for revision, rewriting, rephrasing, addition of more recent material, or any other significant change from the final edited manuscript. There are three good reasons why you should not make substantial changes in the proofs.

First, an ethical consideration: Since neither proofs nor changes in the proofs are seen by the editor unless the journal is a small one-person operation, it simply is not proper to make substantive changes. The paper approved by the editor, after peer review, is the one that should be printed, not some new version containing material not seen by the editor and the reviewers.

Second, it is not wise to disturb typeset material, unless it is really necessary, because new typographical errors may be introduced.

Third, corrections can be expensive. Therefore you should not abuse the publisher (possibly a scientific society of which you are an otherwise loyal member) by requesting unessential changes; in addition, you just might receive a substantial bill for author’s alterations. Most journals absorb the cost of a reasonable number of author’s alterations, but many, especially those with managing editors or business managers, will sooner or later crack down on you if you are patently guilty of excessive alteration of the proofs.

One type of addition to the proofs is frequently allowed. The need arises when a paper on the same or a related subject is published while yours is in process. In light of the new study, you might be tempted to rewrite several portions of your paper. You must resist this temptation, for the reasons stated previously. What you should do is prepare a short addendum in proof (at most a few sentences), describing the general nature of the new work and giving the literature reference. If the editor approves including it, the addendum can then be printed at the end without disturbing the body of the paper.

6. ADDITION OF REFERENCES

Quite commonly, a new paper appears that you would like to add to your references; in doing so you would not need to make any appreciable change in the text, other than adding a few words, perhaps, and the number of the new reference. If you are unsure how the journal would like you to proceed, consult its editorial office.

If the journal employs the numbered, alphabetized reference system, you may be asked to add the new reference with an “a” number. For example, if the new reference would alphabetically fall between references 16 and 17, the new reference would be listed as “16a.” In that way, the numbering of the rest of the list need not be changed. Thus would be avoided the cost and the potential for error of renumbering the references in the reference list and the text. An analogous procedure may be requested for references in the citation order system. Conveniently, if the new reference is cited in an addendum, it would appear last in the citation order system, thus not disrupting the rest of the reference list.

7. PROOFING THE ILLUSTRATIONS

It is important to examine carefully the proofs of the illustrations. In the era when authors submitted photographic prints and other hard-copy illustrations, one needed to check carefully for quality of reproduction. Now that illustrations are being submitted electronically, such need has diminished. Nevertheless, checking illustrations remains important. Make sure that all illustrations are present, complete, and appropriately placed. Also make sure that electronic gremlins have not somehow disturbed or distorted the illustrations. If you perceive problems with the illustrations, report them as instructed by the journal.

8. WHEN TO COMPLAIN

If you have learned nothing else from this chapter, we trust that you now know that you must provide quality control. Too many authors have complained after the fact (after publication) without ever realizing that only they could have prevented whatever it is they are complaining about. For example, authors many times have complained that their pictures have been printed upside down or sideways. When such complaints have been checked, it has commonly been found that the author failed to note that the photo was oriented incorrectly in the proof.

So, if you are going to complain, do it at the proof stage. And, believe it or not, your complaint is likely to be received graciously. Publishers have invested heavily in setting the specifications that can provide quality reproduction. They need your quality control, however, to ensure that their money is not wasted.

Good journals are printed by good printers, hired by good publishers. The published paper will have your name on it, but the reputations of both the publisher and the printer are also at stake. They expect you to work with them in producing a superior product. Likewise, if a journal is solely electronic, the publisher wants to ensure that the product is of high quality and depends on your collaboration in that regard.

Because managing editors of such journals must protect the integrity of the product, those we have known would never hire a printer exclusively on the basis oflow bids. John Ruskin was no doubt right when he said, “There is hardly anything in the world that somebody cannot make a little worse and sell a little cheaper, and the people who consider price only are this person’s lawful prey.”

A sign in a printing shop made the same point:

PRICE

QUALITY

SERVICE

Pick any two of the above

9. REPRINTS

Customarily, authors have received with their proofs a form for ordering hardcopy reprints of their articles. Older scientists remember the days—before widespread electronic access to journal articles, and indeed before widespread access to photocopying—when obtaining reprints from authors served as an important way to keep up with the literature. As well as giving researchers access to articles, reprint requests helped authors learn who was interested in their work (Wiley 2009).

Today, reprints are much less a part of scientific culture. Nevertheless, they sometimes remain worth ordering (for example, to share with colleagues in countries with limited access to the journal literature, to have available at poster presentations or job interviews, or to impress your mother or prospective spouse). Norms regarding reprints differ among research fields. If you are unfamiliar with those in yours, seek colleagues’ guidance on whether to order reprints and, if so, how to use them.

Some journals also make available “electronic reprints,” which allow authors to grant one-time electronic access to their articles. Someday scientists may ask why articles that authors share are called reprints at all.

10. PUBLICIZING AND ARCHIVING YOUR PAPER

In the era when paper reprints prevailed, scientists commonly sent them to colleagues worldwide soon after publishing a paper. Today many scientists alert others to their new articles largely through social media. Depending on their preferences and the scientific cultures where they work, they may, for instance, tweet news of the publication on Twitter and post it on Facebook. They also may add listings (and links) to their ORCID records, LinkedIn profiles, and profiles on science-related networking sites such as ResearchGate. When you publish an article, such steps—and the follow-up by those who thus notice the article and inform others in their networks—can inform those potentially interested in your paper.

General media too can aid in publicizing your newly published research, both to the public and to fellow researchers. Many universities and other research institutions have public information officers (PlOs) whose role is largely to publicize the research done there. When you have a paper accepted, alert a PIO at your institution. He or she can then consider whether to publicize the research to journalists and others, for instance through news releases, institutional websites and publications, and use of social media networks. PIOs know that some journals place articles under embargoes; in other words, research reported in them is not to appear in the media until the release date for the issue in which they are published. A PIO can aid in obtaining timely coverage without violating embargoes. Advice on working with PIOs appears in an article by Tracy Vence (2015) in The Scientist.

Publicizing a newly published paper—through social media, mass media, or other means—can benefit a scientist in multiple ways, notes PIO Matt Shipman (2015). For example, it can lead to citations, please funding agencies, engender collaborations, and more generally expand one’s professional network. It also may attract potential graduate students—or perhaps, earlier in one’s career, attract attention of employers or postdoctoral-fellowship sites. And if your findings have applications outside the research sector, publicity may bring them to the attention of those who can use them there. Indeed, if research is supported with public funds, scientists may be morally obligated to get the word out. In fact, some public and other sources of research funds require that grant recipients make their work openly available.

Whether required or not, making your journal articles (and reports based on them) widely available can benefit science, society, and your career. Follow, of course, the policies of relevant funding agencies regarding public access to papers resulting from your research. (An example is the U.S. National Institutes of Health public access policy, publicaccess.nih.gov/policy.htm.) If your university or other institution has an institutional archive, explore depositing electronic copies of your publication there. Also consider linking publications to your own website or your curriculum vitae. The SHERPA/RoMEO website, www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo, includes information on journal publishers’ policies on self-archiving.

In short, publishing a journal article, though a major accomplishment, is not the last step in getting word out about your research. In ways, it is just the beginning. You have invested great effort in doing the research, writing a paper about it, and publishing the paper. Now take the additional steps to help ensure that, in the broadest sense, your paper has maximum impact.

11. CELEBRATING PUBLICATION

As noted, publishing a scientific paper is a major accomplishment. By the time a paper comes out, you may well be working on the next paper—or even the one after. But take some time to celebrate your success. Some scientists or research groups have traditions for doing so. For example, some gather for a celebration dinner and post a photo taken there. Some treat themselves to a good bottle of wine and collect the labels as reminders of their success. Some may attend a concert, play, or athletic event and keep the tickets or program as mementos. Perhaps best of all is to spend some time—perhaps at a favorite park—with the family members or friends who tolerated our absences, insecurities, and complaints as we struggled to write about and publish the work. Whatever you choose, you deserve to celebrate. Congratulations on publishing your paper!

Source: Gastel Barbara, Day Robert A. (2016), How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, Greenwood; 8th edition.

very nice post, i certainly love this web site, carry on it

Valuable information. Fortunate me I discovered your website by chance, and I am shocked why this coincidence didn’t came about in advance! I bookmarked it.