Human resource management involves recruiting, selecting, training, compensating, and supervising personnel in a manner consistent with the retailer’s organization structure and strategy mix. Personnel practices depend on the line of business, number of employees, store location, and other factors. Because good personnel are needed to develop and carry out strategies, and labor costs can amount to 50 percent or more of expenses, the value of human resource management is clear.

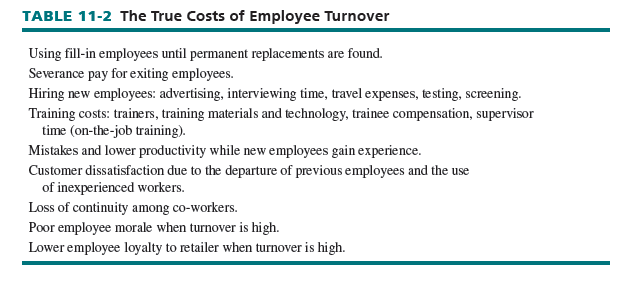

Retailing in the United States employs 25 million people. Thus, there is a constant need to attract new employees—and retain existing ones. For example, as many as 2 million fast-food workers are aged 16 to 20, and they stay in their jobs for short periods. In general, retailers need to reduce the turnover rate; when workers quickly exit a firm, the results can be disastrous. See Table 11-2. Turnover in retail averages around 66 percent for part-time hourly, whereas it drops to 27 percent for full-time employees with benefits such as health insurance.3

Consider the approaches of Target, Zappos, and Wegmans Food Markets:

- Target is committed to employee development and retention. Target challenges employees to innovate, collaborate, and efficiently and intelligently provide the best possible shopping experience to customers. It believes empowering and training employees and providing them with opportunities for professional growth will help its business stay competitive. Every entry- level employee, whether hourly or full time, is mentored by the store team leader. Campus recruits are encouraged to join the summer internship program in Minneapolis where they are trained in leadership skills as well as their functional area (planning, software training, etc.) to be a successful member of a Target store/distribution center, corporate, or technology leadership team. Company benefits include health coverage, a pension, a 401(K) plan, tuition reimbursement, life insurance, a paid vacation, and an annual bonus.

- Zappos, an online retailer of shoes, apparel, and accessories (owned by Amazon.com Inc. since 2009) says its goal is to be the online service leader. Employees call themselves “Zap- ponians” and claim they “Live to Deliver WOW” in support of the first core value of the firm. Employees get benefits such as vacation and sick days, a retirement plan, life and disability insurance, medical and dental coverage, maternity and paternity leave, tuition reimbursement, discounts (40%) on Zappos merchandise, and free shipping. Zappos helps employees stay fit by having an on-site fitness center, a yoga studio, weight management programs, and fitness challenges. To help employees achieve a work-life balance, Zappos pays for dry cleaning, car washes, and oil changes; it even has an on-site library and life coach, health screening, and a nap room! Company happy hours, fun events, and healthy on-site catering build team and family spirit.5

- Wegmans Food Markets is the only retailer on the Forbes “100 Best Companies to Work For” list every year since 1998.6 It offers health insurance to part-timers, telecommuting, job sharing and compressed work weeks, tuition reimbursement, paid vacations, and substantial training. Full-time employee turnover is low. Wegmans has multiple paths to career success via lateral learning, cross-training, internships, and management training. Wegmans cares about the well-being of employees and empowers them to make decisions that customers and the company.7

1. The Special Human Resource Environment of Retailing

Retailers face a human resource environment characterized by a large number of inexperienced workers, long hours, highly visible employees, a diverse work force, many part-time workers, and variable customer demands. These factors complicate employee hiring, staffing, and supervision.

The need for a large retail labor force often means hiring those with little or no prior experience. Sometimes, a position in retailing represents a person’s first “real job.” People are attracted to retailing because they find jobs near to home, and retail positions (such as cashiers, stock clerks, and some types of sales personnel) may require limited education, training, and skill. Also, the low wages paid for some positions result in the hiring of inexperienced people. Thus, high employee turnover and cases of poor performance, lateness, and absenteeism may result.

The long working hours in retailing, which may include weekends, turn off certain prospective employees. Many retailers now have longer hours because more shoppers want to shop during evenings and weekends. Accordingly, some retailers require at least two shifts of full-time employees.

Retailing employees are highly visible to the customer. Thus, when personnel are selected and trained, special care must be taken as to their manners and appearance. Some small retailers do not place enough emphasis on employee appearance (neat grooming and appropriate attire).

It is common for retailers to have a diverse labor force, with regard to age, work experience, gender, race, and other factors. This means that firms must train and supervise their workers so they interact well with one another—and are sensitive to the perspectives and needs of each other. Home Depot’s recruitment strategy includes partnerships with several national nonprofit, government, and educational organizations to reach out to the communities it serves and to attract a broad range of qualified candidates with diverse backgrounds, including AARP, NAACP, National Urban League, National Society of Hispanic MBAs, National Black MBA Association Inc., and several U.S. military groups. In addition, Home Depot provides resources to help recruits succeed through Associate Resource groups and online tools such as “Military Skills Translator” to help veterans identify positions and job descriptions that leverage skills acquired in the military.8

Due to long operating hours, retailers regularly hire part-time workers. In many supermarkets, more than half the workers are part-time, and problems may arise. Some part-time employees are more lackadaisical, late, absent, or likely to quit than full-time employees. They must be closely monitored. Like other firms, retailers hire a large number of Millennials. Although this group is generally technologically advanced, Millennials often have different work values than older employees. A recent Gallup Poll found that Millennials are the least engaged group in the work force.9 Here are a number of ways to better motivate Millennials:10

- Show the firm’s commitment to society and respected charities by supporting volunteerism.

- Train managers to communicate frequently and openly with Millennials.

- Get Millennials actively involved in solving important problems.

- Provide Millennials with mentors.

- Accommodate Millennials’ needs with flexible hours.

Variations in customer demand by day, time period, or season may cause difficulties. A number of U.S. shoppers make major supermarket trips on Saturday or Sunday. So, how many employees should there be Monday through Friday and how many on Saturday and Sunday? Differences by time of day (morning, afternoon, evening), season, and holidays also affect planning. When stores are very busy, even administrative and clerical employees may be needed on the sales floor.

As a rule, retailers should consider these points:

- Recruitment and selection procedures must efficiently generate sufficient applicants.

- Some training must be short because workers are inexperienced and temporary.

- Compensation must be perceived as “fair” by employees.

- Advancement opportunities must be available to employees who view retailing as a career.

- Employee appearance and work habits must be explained and reviewed.

- Diverse workers must be taught to work together well and amicably.

- Morale problems may result from high turnover and the many part-time workers.

- Full- and part-time workers may conflict, especially if some full-timers are replaced.

Various retail career opportunities are available to women and minorities. There is still some room for improvement, however.

WOMEN IN RETAILING Retailers have made a lot of progress in career advancement for women. According to the “2020 Women on Boards,” Ann Inc., Avon, Chico’s, Children’s Place, Estee Lauder, HSN (Home Shopping Network), Macy’s, Ulta, and Williams-Sonoma Inc. are among the U.S. public firms with 40 percent or more of corporate officers who are women.11 The “2013 Catalyst Census: Fortune 500 Women’s Representation by NAICS Industry” report notes that retailing has the highest percentage of women as corporate officers among the 18 industry groups.

Women have more career options in retailing than ever before, as the following examples show. Mary Kay Ash (Mary Kay cosmetics), Debbi Fields (Mrs. Fields’ Cookies), and Lillian Vernon (the direct marketer) have founded retailing empires. As of 2016, women were chief executive officers in 21 of Fortune 500 companies overall and/or chairpersons of the board of such U.S.-based retailers as Enterprise, Home Shopping Network, Ross Stores, Sam’s Club, and Victoria’s Secret.12 Let’s look at a brief profile of two of these.

Rosalind Brewer is president and CEO of Sam’s Club. She started her career with Walmart in 2006 as regional vice-president of operations. She then was promoted to division president of Walmart Southeast, and then president of Walmart East. In 2012, Brewer was named president and CEO of Sam’s Club. She earned her bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Spelman College. In 2015, Forbes referred to Rosalind Brewer as one of the “World’s 100 Most Powerful Women.”13

At Enterprise Holdings Inc., the parent company of Enterprise, Alamo, and National car- rental service providers with more than $19 billion in annual revenues, Pamela Nicholson has been president and CEO since 2013. She is the highest-ranking woman among the world’s largest travel companies and has been named to Fortune’s list of “America’s 50 Most Powerful Women in Business” every year since 2007. Nicholson graduated from the University of Missouri with a bachelor of arts degree and began her career with Enterprise Rent-A-Car in 1981 as a management trainee. She has grown the U.S. and international businesses and has been working on a deal with Nissan for a car-sharing businesses for students at 90 college campuses.14

Despite recent progress, women still account for a small percentage of corporate officers at publicly owned retailers. These initiatives can help to increase the number of female executives:

- Meaningful training programs

- Advancement opportunities

- Telecommuting and flex time—the ability of employees to adapt their work hours

- Job sharing among two or more employees who each work less than full-time

- Onsite child care

MINORITIES AND DIVERSITY IN RETAILING Fortune’s 2016 “100 Best Companies to Work For” study listed the top companies’ minority statistics. Among retailers with a high percent of minorities are Ikea (52 percent minorities), Nordstrom (50 percent), Whole Foods (43 percent), CarMax (41 percent), Nugget Market (40 percent), Build-A-Bear (35 percent), Container Store (30 percent), Wegmans Food Markets (21 percent), and REI (17 percent).15

As with women, retailers have done many good things in the area of minority employment, but there is still more to be accomplished. Consider these positive examples:

- CarMax strongly believes in having a diverse work force—and not just because it wants to be a good corporate citizen. CarMax knows that employee diversity contributes to its already strong competitive advantages. Through such diversity, CarMax has a broader view of the marketplace and attracts a greater range of customers. It continuously strives to treat every job applicant, employee, customer, and supplier with respect and fairness—regardless of gender, race, sexual orientation, age, and various other factors.16

- Walmart is committed to embracing diversity on all aspects of its organization; from its associates to its supplier partners. Through its Supplier Diversity Program,17 Walmart works with over 3,000 suppliers owned and operated by minorities, women, veterans, and disabled people. In fiscal 2016, Walmart purchased $14.7 billion from women and minority-owned businesses.

- Walgreens shows its commitment to diversity as part of a multipronged effort. It includes dealing with a minimum of 8 percent certified minority business firms and 2 percent other certified diversified businesses; and it encourages prime suppliers to use diverse suppliers.18

The following list suggests some ways for retailers to even better address the needs of minority workers:

- Have clear policy statements from top management as to the value of employee diversity.

- Engage in active recruitment programs to stimulate minority applications.

- Offer meaningful training programs.

- Provide advancement opportunities.

- Have zero tolerance for insensitive workplace behavior.

2. The Human Resource Management Process in Retailing

The human resource management process consists of these interrelated personnel activities: recruitment, selection, training, compensation, and supervision. The goals are to obtain, develop, and retain employees. When applying the process, diversity, labor laws, and privacy should be reflected.

Diversity involves two premises: (1) employees must be hired and promoted in a fair and open way, without regard to gender, ethnic background, and other related factors; and (2) in a diverse society, the workplace should be representative of such diversity.

There are several aspects of labor laws for retailers to satisfy:

- Do not hire underage workers.

- Do not pay workers “off the books” (“under the table”).

- Do not require workers to engage in illegal acts (such as bait-and-switch selling).

- Do not discriminate in hiring or promoting workers.

- Do not violate worker safety regulations.

- Do not disobey the Americans with Disabilities Act.

- Do not deal with suppliers that disobey labor laws.

Retailers must also be careful not to violate employees’ privacy rights. Only necessary data about workers should be gathered and stored, and such information should not be freely disseminated.

We now discuss each human resource management activity for sales and middle-management jobs. For further insights, go to our blog (www.bermanevansretail.com).

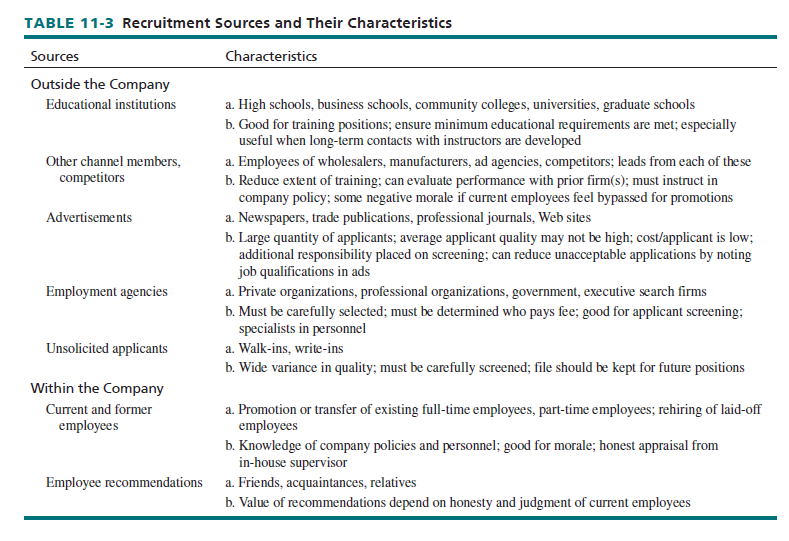

RECRUITING RETAIL PERSONNEL Recruitment is the activity whereby a retailer generates a list of job applicants. Table 11-3 indicates the features of several key recruitment sources. In addition to these sources, the Web now plays a bigger role in recruitment. Many retailers have a career or job section at their Web site, and some sections are as elaborate as the overall sites. Visit Target’s Web site (www.target.com), for example. Scroll down to the bottom of the home page and click on “more” and then “careers.”

With entry-level sales jobs, retailers rely on educational institutions, ads, walk-ins (or write- ins), Web sites (including social media), and employee referrals. With middle-management positions, retailers rely on employment agencies, competitors, ads, and employee referrals. A retailer’s usual goal is to generate a list of potential employees, which is reduced during selection. Firms that accept applications only from those meeting minimum standards save a lot of time and money.

SELECTING RETAIL PERSONNEL The company next selects new employees by matching the traits of potential employees with specific job requirements. Job analysis and description, the application blank, interviewing, testing (optional), references, and a physical exam (optional) are tools in the process; they should be integrated.

In job analysis, information is amassed on each job’s functions and requirements: duties, responsibilities, aptitude, interest, education, experience, and physical tasks. It is used to select personnel, set performance standards, and assign salaries. Thus, department managers often act as the main sales associates for their areas, oversee other sales associates, have some administrative duties, report to the store manager, are eligible for bonuses, and receive $25,000 to $45,000+ annually.

Job analysis should lead to written job descriptions. A traditional job description contains a position’s title, relationships (superior and subordinate), and specific roles and tasks. Figure 11-4 showed a store manager description. Yet, using a traditional description alone has been criticized. It may limit a job’s scope, as well as its authority and responsibility; not let a person grow; limit activities to those listed; and not describe how jobs are coordinated. To complement a traditional description, a goal-oriented job description enumerates basic functions, the relationship of each job to overall goals, the interdependence of positions, and information flows. See Figure 11-10.

An application blank is usually the first tool used to screen applicants; it provides data on education, experience, health, reasons for leaving prior jobs, outside activities, hobbies, and references. It is usually short, requires little interpretation, and can be used as the basis for probing in an interview. With a weighted application blank, factors having a high relationship with job success are given more weight than others. Retailers using such a form analyze current and past employee performance and determine the criteria (education, experience, etc.) best correlated with job success (as measured by longer tenure, better performance, etc.). After weighted scores are awarded to all job applicants (based on data they provide), a minimum total score becomes a cutoff point for hiring. An effective application blank aids retailers in lessening turnover and selecting high achievers.

An application blank should be used along with a job description. Those meeting minimum job requirements are processed further; others are immediately rejected. In this way, the application blank provides a quick and inexpensive method of screening.

The interview seeks information that can be amassed only by personal questioning and observation. It lets an employer determine a candidate’s verbal ability, note his or her appearance, ask questions keyed to the application, and probe career goals. Interviewing decisions must be made about the level of formality, the number and length of interviews, the location, the person(s) to do the interviewing, and the interview structure. These decisions often depend on the interviewer’s ability and the job’s requirements.

Small firms tend to hire applicants based on their performance during interviews. Large firms may have multiple stages: candidates who excel at the interview stage may then be required to take psychological tests (to measure personality, intelligence, interest, and leadership), and/or achievement tests (to measure learned knowledge).19

Tests must be administered by qualified people. Standardized exams should not be used unless proven effective in predicting job performance. Achievement tests deal with specific skills or information (such as the ability to make a sales presentation), are easier to interpret than psychological tests, and show direct relationships between knowledge and ability. In administering tests, firms must not violate federal, state, and local laws. The federal Employee Polygraph Protection Act bars firms from using lie detector tests in most hiring situations (drugstores are exempt).

To save time and operate more efficiently, some retailers—large and small—use computer ized application blanks and testing. Advance Auto Parts, Babies “R” Us, Best Buy, CVS, Family Tree, Lowe’s, and PetSmart are among those with in-store kiosks that allow people to apply for jobs, complete applications, and answer questions. This speeds the process and attracts applicants.

Many retailers get references from applicants that can be checked either before or after an interview. References are contacted to see how enthusiastically they recommend an applicant, check the applicant’s honesty, and ask why an applicant left a prior job. Mail and phone checks are inexpensive, fast, and easy.

Some firms require a physical exam because of the physical activity, long hours, and tensions involved in many retailing positions. A clean bill of health means the candidate is offered a job. Again, federal, state, and local laws must be followed.

Each step in the selection process complements the others; together they give the retailer a good information package for choosing personnel. As a rule, retailers should use job descriptions, application blanks, interviews, and reference checks. Follow-up interviews, psychological and achievement tests, and physical exams depend on the retailer and the position. Inexpensive tools (such as application blanks) are used in the early screening stages; more costly, in-depth tools (such as interviews) are used after reducing the applicant pool. Equal opportunity, nondiscriminatory practices must be followed.

TRAINING RETAIL PERSONNEL Every new employee should receive pre-training, an indoctrination on the firm’s history, culture, and policies, job orientation on hours, compensation, the chain of command, and job duties. The term onboarding describes the process of integrating new employees into an organization and its culture, and understanding the expectations of their new job. New employees should be introduced to co-workers; encouraged to build relationships with a diverse network of colleagues; and provided with tools, resources, and knowledge to become successful and productive. A well-designed onboarding process may evolve over an entire year— from new employee orientation to continuous improvement. It should be modified for specific job roles and locations and make the employee feel welcome.20

Training programs teach new (and existing) personnel how best to perform their jobs or how to improve themselves. Training can range from 1-day sessions on operating a computerized cash register, personal selling techniques, or compliance with affirmative action programs to 2-year programs for executive trainees on all aspects of the retailer and its operations:

- For each new employee, Container Store provides extensive formal training, which includes understanding its “Employee First Culture,” systems training, and classes on how to perform multiple jobs. Each first-year, full-time employee receives about 260 hours of training. The New Store Trainer program has three phases: pre-training (3 weeks prior to opening), postsupport (week of and after grand opening), and post-training (a few weeks after post-support). The training ensures that employees are knowledgeable and empowered to offer the customer service the retailer is known for in the industry.21

- Best Buy uses an online “Learning Lounge” (www.bestbuylearninglounge.com) to facilitate employee training for new and continuing workers, to keep employees current on the firm’s best practices, and to let employees easily communicate with one another. The passwordprotected portal is under the auspices of Best Buy’s Retail Training & Development group, whose slogan is “grow. perform. succeed.”

Training should be an ongoing activity. New equipment, legal changes, new product lines, job promotions, low employee morale, and employee turnover necessitate not only training but also retraining. Macy’s has a program called “Clienteling,” which tutors sales associates on how to have better long-term relations with specific repeat customers. Core vendors of Macy’s teach sales associates about the features and benefits of new merchandise when it is introduced.22

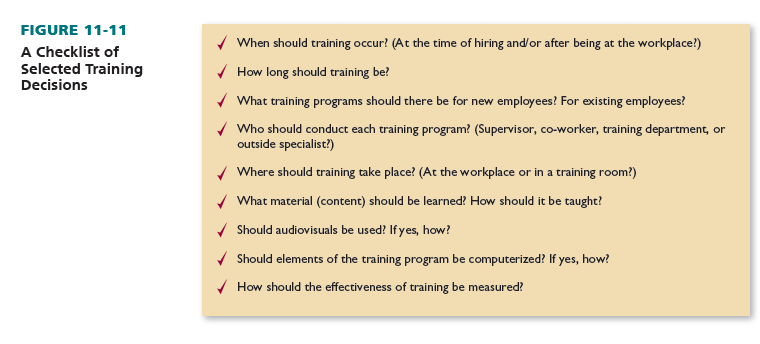

There are several training decisions, as shown in Figure 11-11. They can be divided into three categories: identifying needs, devising appropriate training methods, and evaluation.

Short-term training needs can be identified by measuring the gap between the skills that workers already have and the skills desired by the firm (for each job). This training should prepare employees for possible job rotation, promotions, and changes in the company. A longer training plan lets a firm identify future needs and train workers appropriately.

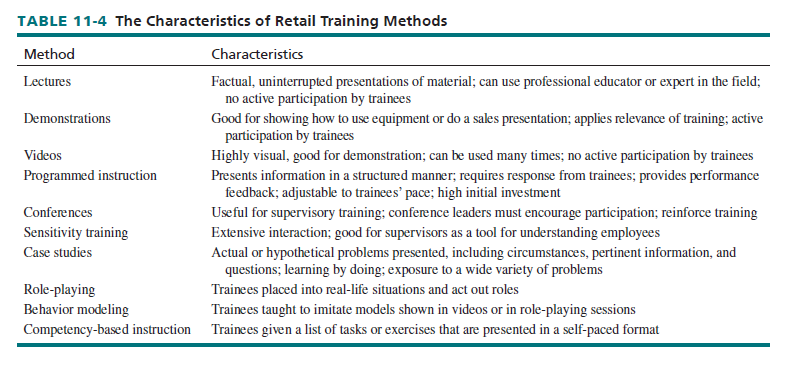

There are many training methods for retailers: lectures, demonstrations, videos, programmed instruction, conferences, sensitivity training, case studies, role-playing, behavior modeling, and competency-based instruction. Some techniques may be computerized, as evidenced by more and more firms.. The attributes of the various training methods are noted in Table 11-4. Retailers often use more than one technique to reduce employee boredom and to cover the material better.

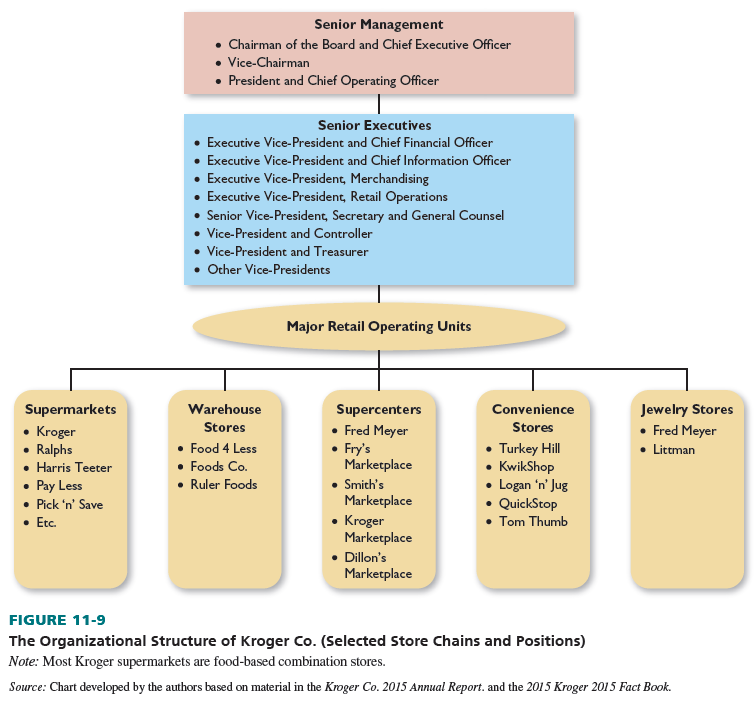

Computer-based training software is available from a variety of vendors. For example, TiERl Performance Solutions has numerous modules that have been used to train retail employees in such areas as point-of-sales systems, labor scheduling, customer service, manager training, store operations, merchandise management, and more. Among its many clients are CDW, Kroger, Macy’s, McDonald’s, Petco, and Wendy’s.

For training to succeed, a conducive environment is needed, based on several principles:

- All people can learn if taught well; there should be a sense of achievement.

- A person learns better when motivated; intelligence alone is not sufficient.

- Learning should be goal-oriented.

- A trainee learns more when he or she participates and is not a passive listener.

- The teacher must provide guidance, as well as adapt to the learner and to the situation.

- Learning should be approached as a series of steps rather than a one-time occurrence.

- Learning should be spread out over a reasonable period of time rather than be compressed.

- The learner should be encouraged to do homework or otherwise practice.

- Different methods of learning should be combined.

- Performance standards should be set and good performance recognized.

A training program must be regularly evaluated. Comparisons can be made between the performance of those who receive training and those who do not, as well as among employees receiving different types of training for the same job. Evaluations should always be made in relation to stated training goals. In addition, training effects should be measured over different time intervals (such as immediately, 30 days later, and 6 months later), and proper records maintained.

COMPENSATING RETAIL PERSONNEL Total compensation—direct monetary payments (salaries, commissions, and bonuses) and indirect payments (paid vacations, health and life insurance, and retirement plans)—should be fair to both the retailer and its employees. To better motivate employees, some firms also have a profit-sharing plan. Smaller retailers often pay salaries, commissions, and/or bonuses and have fewer fringe benefits. Bigger ones generally pay salaries, commissions, and/ or bonuses and offer more fringe benefits.

Although the hourly federal minimum wage has been $7.25 since July 2009, 45 states have their own laws—29 are higher than the federal minimum and two are lower. In 2016, the highest minimum wage was in Washington, D.C. ($11.50), and in these states: California and Massachusetts ($10.00); Alaska, ($9.75); and Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Vermont ($9.60). Some states and cities are phasing in a minimum wage as high as $15.00 per hour. The minimum wage has the most impact on retailers hiring entry-level, part-time workers. Full-time, career-track retailing jobs are typically paid an attractive market rate; to attract part-time workers in good economic times, retailers must often pay salaries above the minimum.

At some firms, compensation for certain positions is set through collective bargaining. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 825,000 retail employees are represented by labor unions. Yet, union membership varies greatly. Unionized grocery stores account for more than one-half of total U.S. supermarket sales, whereas independent supermarkets are not usually unionized.

With a straight salary, a worker is paid a fixed amount per hour, week, month, or year. Advantages are retailer control, employee security, and known expenses. Disadvantages are retailer inflexibility, the limited productivity incentive, and fixed costs. Clerks and cashiers are usually paid salaries. With a straight commission, earnings are directly tied to productivity (such as sales volume). Advantages are retailer flexibility, the link to worker productivity, no fixed costs, and employee incentive. Disadvantages are the retailer’s potential lack of control over the tasks performed, the risk of low earnings to employees, cost variability, and the lack of limits on worker earnings. Sales personnel for autos, real-estate, furniture, jewelry, and other expensive items are often paid a straight commission—as are direct-selling personnel.

To combine the attributes of salary and commission plans, retailers may pay employees a salary plus commission. Shoe salespeople, major appliance salespeople, and some management personnel are among those paid this way. Sometimes, bonuses supplement salary and/or commission, usually for outstanding performance. At Finish Line footwear and apparel stores, regional, district, and store managers receive salaries and earn bonuses based on sales, payroll size, and theft goals. In certain cases, executives are paid via a “compensation cafeteria” and choose their own combination of salary, bonus, fringe benefits, life insurance, stock, and retirement benefits.

A thorny issue facing retailers today involves the benefits portion of employee compensation, especially as related to pensions and health care. It is a challenging time due to intense price competition, the use of part-time workers, and escalating medical costs as retailers try to balance their employees’ needs with company financial needs.

SUPERVISING RETAIL PERSONNEL Supervision is the manner of providing a job environment that encourages employee accomplishment. The goals are to oversee personnel, attain good performance, maintain morale, motivate people, control costs, communicate, and resolve problems. Supervision is provided by personal contact, meetings, and reports.

Every firm wants to continually motivate employees so as to harness their energy on behalf of the retailer and achieve its goals. Job motivation is the drive within people to attain work- related goals. It may be positive or negative. These questions can be used to help predict employee behavior, based on their motivation:

- Do you like the work you do? Does it give you a sense of accomplishment?

- Are you proud to say you work with us?

- Does the work expected from you influence your overall job attitude? How?

- Do physical working conditions influence your overall job attitude? How?

- Does the way you are treated by your boss affect your job attitude?

- Do you understand the firm’s strategy?

- Do you see a connection between your work and the firm’s strategic goals?23

Employee motivation should be approached from two perspectives: What job-related factors cause employees to be satisfied or dissatisfied with their positions? What supervision style is best for both the retailer and its employees? See Figure 11-12.

Each employee looks at job satisfaction in terms of minimum expectations (“dissatisfi- ers”) and desired goals (“satisfiers”). A motivated employee requires fulfillment of both factors.

Minimum expectations relate mostly to the job environment, including a safe workplace; equitable treatment for those with the same jobs; some flexibility in company policies (such as not docking pay if a person is 10 minutes late); an even-tempered boss; some freedom in attire; a fair compensation package; basic fringe benefits (such as vacation time and medical coverage); clear communications; and job security. These elements can generally influence motivation in only one way—negatively. If minimum expectations are not met, an employee will be unhappy. If these expectations are met, they are taken for granted and do little to motivate the person to go “above and beyond.”

Desired goals relate more to the job than to the work environment. They are based on whether an employee likes the job, is recognized for good performance, feels a sense of achievement, is empowered to make decisions, is trusted, has a defined career path, receives extra compensation when performance is exceptional, and is given the chance to learn and grow. These elements can have a huge impact on job satisfaction and motivate a person to go “above and beyond.” Nonetheless, if minimum expectations are not met, an employee might still be dissatisfied enough to leave, even if the job is quite rewarding.

There are three basic styles of supervising retail employees:

- Management assumes that employees must be closely supervised and controlled and that only economic inducements really motivate. Management further believes that the average worker lacks ambition, dislikes responsibility, and prefers to be led. This is the traditional view of motivation and has been applied to lower-level retail positions.

- Management assumes employees can be self-managers and assigned authority, motivation is social and psychological, and supervision can be decentralized and participatory. Management also thinks that motivation, the capacity for assuming responsibility, and a readiness to achieve company goals exist in people. The critical supervisory task is to create an environment so people achieve their goals by attaining company objectives. This is a more modern view and applies to all levels of personnel.

- Management applies a self-management approach and also advocates more employee involvement in defining jobs and sharing overall decision making. There is mutual loyalty between the firm and its workers, and both parties enthusiastically cooperate for the long-term benefit of each. This is also a modern view and applies to all levels of personnel.

It is imperative to motivate employees in a manner that yields job satisfaction, low turnover, low absenteeism, and high productivity. Research in organizational behavior on employee motivation suggests that trade-offs among command, autonomy, respect for employees’ need for self-determination and economic incentives can improve employee intrinsic motivation and performance. Some suggestions include: (1) Empower employees to solve problems. (2) Ask employees for their input. (3) Regularly communicate with employees about how they are doing. (4) Delegate tasks. (5) Encourage new ideas from employees. (6) Let employees learn from their mistakes without being unduly harsh. (7) Show employees what is needed for promotions. (8) Provide public recognition of good performance. (9) Seek employee input on company goals and how to achieve them.24

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Great insights and useful tips. Thank you for sharing your blog and keep posting.