Differences in forecasting and budgeting procedures, management philosophy, selling problems, and executive judgment, as well as variations in target-setting procedures, cause each firm to have somewhat unique targets. Ignoring small differences, however, targets fall into four categories: (1) sales volume, (2) budget, (3) activity, and (4) combination. Differences in procedures show up mainly in the setting of sales volume and budget targets.

1. Sales Volume Targets

The sales volume target is the oldest and most common type. It is an important standard for appraising the performances of individual sales personnel, other units of the sales organization, and distributive outlets. Sales volume targets communicate managements’ expectations as to “how much for what period.” Sales volume targets are set for geographical areas, product lines, or marketing channels or for one or more of these in combination with any unit of the sales organization, the exact design depending upon what facets of the selling operation management wants to appraise or motivate.

The smaller the selling unit, the more effective a target is for controlling sales operations. Setting a sales volume target for a sales region, for example, obtains some direction and control, but setting sales volume targets for each sales territory in the region obtains much more. Setting sales volume targets for smaller selling units makes it less likely that good or bad sales performance in one aspect of the selling operation will be obscured by offsetting performance in other aspects. The same holds for sales volume targets on products or time periods—more direction and control are secured by setting targets for individual products rather than for entire product lines, and for short periods rather than long.

Sales volume targets see extensive use. Sales executives set them and the sales volume objective dominates other objectives. Before profits are earned, some sales volume level must be attained. It is entirely logical for sales management first to set standards for sales volume performance. Sales personnel readily grasp the significance of sales volume targets. However, sales management should not deemphasize earning of profits or conserving on selling expense. Sales volume alone, although important, is not sufficient—profits are necessary for survival.

Dollar sales volume targets. Companies selling broad product lines set sales volume targets in dollars rather than in units of product. These companies meet complications in setting unit targets and in evaluating sales performance for individual products. A key advantage of the dollar terminology is that the dollar sales volume targets relate easily to other performance data, such as selling expenses, through ratios or percentages. In addition, when products have no established prices, and sales personnel have discretion in cutting prices, either dollar volume targets or combined dollar and unit volume targets assure that sales personnel do not cut prices too deeply to build unit volume.

Unit sales volume targets. Sales volume targets in units of product are used in two situations. One is that in which prices fluctuate considerably; in this situation, unit sales volume targets are better yardsticks than are dollar sales volume targets. If a product is now priced at $80 a unit, 600 units sold means $48,000 in sales, but if the price rises by 25 percent (to $100 a unit), only 480 units sold brings in the same dollar volume.

The second situation occurs with narrow product lines sold at stable prices. In this situation, dollar volume and unit volume targets might both appear appropriate, but, especially if unit prices are high, unit targets are preferable for psychological reasons—sales personnel regard a $1 million quota as a higher hurdle than a forty-unit quota for machines priced at $25,000 each.

2. Procedures for Setting Sales Volume Targets

Sales volume targets derived from territorial sales potentials. It seems logical that a sales volume quota should derive from the sales potential present, for example, in a territory. A sales volume quota sums up the effort that a particular selling unit should expend. Sales potential, by definition, represents the maximum sales opportunities open to the same selling unit. Many managements derive sales volume targets from sales potentials, and this approach is appropriate when (1) territorial sales potentials are determined in conjunction with territorial design or (2) bottom-up planning and forecasting procedures are used in obtaining the sales estimate in the sales forecast.

If sales territories are designed and sales personnel assigned according to procedures recommended in Chapter 19, management is justified in setting sales volume targets by calculating the percentage relationship between each territorial sales potential and total sales potential and using the resulting percentages to apportion the company sales estimate among territories. If, for instance, territory A’s sales potential is 2 percent of the total, and the company sales estimate is $20 million, then the sales volume quota for territory A is $400,000. Assuming that no further adjustments are needed, the summation of all territorial sales volume targets equals the company sales estimate. However, total sales potential is generally not equal to the total sales estimate, even though the two figures are related. Sales potentials, for companies as well as for territories, are the sales volumes reachable under ideal conditions, whereas sales estimates and sales volume targets are the sales levels management expects to attain under somewhat less than ideal conditions.

If bottom-up planning and forecasting procedures have been used, management already has considered such factors as past sales, competition, changing market conditions, and differences in personal ability, as well as contemplated changes in prices, products, promotion, and the like—if it has, then the final revised estimates of territorial sales potentials become the territorial sales volume targets. However, in spite of what has just been said, further adjustments are generally advisable because sales volume targets related directly to territorial sales potentials depend upon statistical data underlying estimates of sales potential; in other words, the tempering of experienced judgment is needed for realistic sales volume targets to result. Rarely does a company achieve an ideal territorial design, and to the extent that territorial differences (in coverage difficulty, for instance) have not been taken into account previously, compensating adjustments are made when setting sales volume targets.

Few companies achieve an ideal assignment of sales personnel to territories, so, in setting targets, differences in anticipated personnel effectiveness because of age, energy, initiative, experience, knowledge of the territory and physical condition require adjustments. Moreover, sales volume targets motivate individual sales personnel in different ways—one is thrilled to learn that next year’s target is 50 percent above this year’s, a second is hopelessly discouraged by similar news—and target setters adjust for such differences. Then, too, some companies provide financial motivation by linking compensation to performance against target; this generally means that volume targets are set lower than sales potentials.

Sales volume targets derived from total market estimates. In some companies, management has neither statistics nor sales force estimates of territorial sales potentials. These companies use top-down planning and forecasting to obtain the sales estimate for the whole company; hence, if management sets volume targets, it uses similar procedures. Management may either (1) break down the total company sales estimate, using various indexes of relative sales opportunities in each territory, and then make adjustments (such as those described in the previous section) to arrive at territorial sales volume targets; or (2) convert the company sales estimate into a companywide sales target (by taking into account projected changes in price, product, promotion, and other policies) and then break down the company volume target, by using an index of relative sales opportunities in each territory. In the second procedure, another set of adjustments is made for differences in territories and sales personnel before finally arriving at territorial targets.

Note that these choices are similar, the only difference being whether adjustments are made only at the territorial level, or also at the company level. The second alternative is the better choice. Certain adjustments apply to the total company and to all sales territories; others apply uniquely to individual territories. The two-level approach assumes that both classes of adjustments receive attention.

In companies with more than two organizational levels in the sales department, additional rounds of adjustments are necessary. For instance, consider the company with both sales regions and sales territories. One round of adjustments takes place at the company level, and another at the regional level. Most regional sales managers would want a third round of adjustments before setting territorial sales volume targets, as territorial sales volume targets should not be set finally until after consulting sales personnel assigned to territories. The regional sales manager ordinarily calls in each salesperson to discuss the territorial outlook relative to the share of the regional sales volume target that each territory should produce; then the regional manager’sets territorial sales volume targets. Targets developed in this way are more acceptable to the sales staff, because each has participated in setting them, and each has had the opportunity to contribute information bearing on the final target.

Sales volume targets based on past sales experience alone. A crude procedure is to base sales volume targets solely on past sales experience. One company, for instance, takes last year’s sales for each territory, adds an arbitrary percentage, and uses the results as sales volume targets. A second averages past sales for each territory over several years, adds arbitrary amounts, and thus sets targets for sales volume. The second company’s procedure is the better of the two—by averaging sales figures, management recognizes that the sales trend is important. The averaging procedure evens out the distorting effects of abnormally good and bad years.

Companies using past sales procedures for determining sales volume targets assume not only that past and future sales are related, but that past sales have been satisfactory. These assumptions may or may not be valid, but one thing is certain: companies making them perpetuate past errors. If a territory has had inadequate sales coverage, basing its sales volume target on past sales ensures future inadequate sales coverage. Furthermore, the average-of-past-sales method has a unique defect in that average sales lag behind actual sales during long periods of rising or falling sales. Thus, during these periods targets always are set either too low or too high. Targets based solely on past sales, moreover, make poor performance standards, as previously poor performances go undetected and are built into the standards automatically. Two individuals, for example, may receive identical sales volume targets, even though one realized 90 percent of previous territorial sales potential and the second only 70 percent. Neither knowing nor considering the true sales opportunities in each territory, management perpetuates past inequities. Past sales experience should be considered in setting territorial sales volume targets, but it is only one of many factors to take into account.

Sales-volume targets based on executive judgment alone. Sometimes, sales volume targets are based solely on executive judgment. This is justified when there is little information to use in setting targets. There may be no sales forecast, no practical way to determine territorial sales potential.

The product may be new and its probable rate of market acceptance unknown; the territory may not yet have been opened, or a newly recruited salesperson may have been assigned to a new territory. In these situations, management may set sales volume targets solely on a judgment basis. Certainly, however, targets can be of no higher quality than the judgment of those setting them. Judgment, like past sales experience, is important in determining targets, but it is not the only ingredient.

Sales volume targets related only to compensation plan. Companies sometimes base sales volume targets solely upon the projected amounts of compensation that management believes sales personnel should receive. No consideration is given to territorial sales potentials, total market estimates, and past sales experience, and targets are tailored exclusively to fit the sales compensation plan. If, for instance, salesperson A is to receive a $5,000 monthly salary and a 5 percent commission on all monthly sales over $100,000, A’s monthly sales volume quota is set at $100,000. As long as A’s monthly sales exceed $100,000, management holds A’s compensation-to-sales ratio to 5 percent. Note that A is really paid on a straight-commission plan, even though it is labeled “salary and commission.”

Such sales volume targets are poor standards for appraising sales performance; they relate only indirectly, if at all, to territorial sales potentials. It is appropriate to tie in sales force target performances with the sales compensation plan, that is, as a financial incentive to performance, but no sales volume target should be based on the compensation plan alone, for that is “putting the cart before the horse.”

Letting sales personnel set their own sales volume targets. Some companies turn the setting of sales volume targets over to the sales staff, who are placed in the position of determining their own performance standards. The ostensible reason is that sales personnel, being closest to the territories, know them best and therefore should set the most realistic sales volume targets. The real reason, however, is that management is shirking the target-setting responsibility and turns the whole problem over to the sales staff, thinking that they will complain less if they set their standards. There is, indeed, a certain ring of truth in the argument that having sales personnel set their own objectives may cause them to complain less, and to work harder to attain them. But sales personnel are seldom dispassionate in setting their own targets.

Some are reluctant to obligate themselves to achieve what they regard as “too much”; others—and this is just as common—overestimate their capabilities and set unrealistically high targets. Targets set unrealistically high or low—by management or by the sales force—cause dissatisfaction and low sales force morale. Management should have better information; therefore, it should make final target decisions. How, for instance, can sales personnel adjust for changes management makes in price, product, promotion, and other policies?

3. Budget Targets

Budget targets are set for various units in the sales organization to control expenses, gross margin, or net profit. The intention in setting budget targets is to make it clear to sales personnel that their jobs consist of something more than obtaining sales volume. Budget targets make personnel more conscious that the company is in business to make a profit. Expense targets emphasize keeping expenses in alignment with sales volume, thus indirectly controlling gross margin and net profit contributions. Gross margin or net profit targets emphasize margin and profit contributions, thus indirectly controlling sales expenses.

Expense targets. The setting of expense target plans for reimbursing sales force expenses were analyzed earlier,2 so discussion here focuses on using expense targets in appraising performance. Hardly ever are expense targets used in lieu of other targets; they are supplemental standards aimed toward keeping expenses in line with sales volume. Thus, expense targets are used most often in combination with sales volume targets.

Frequently, management provides sales personnel with financial incentives to control their own expenses. This is done either by tying performance against expense targets directly to the compensation plan or by offering “expense bonuses” for lower expenses than the targets. Expense targets derive from expense estimates in territorial sales budgets. But to reduce the administrative burden and misunderstandings, expense targets are generally expressed not in dollars but as percentages of sales, thus directing attention both to sales volume and the costs of achieving it.

Setting expense targets as sales volume percentages poses some problems. Variations in coverage difficulty and other environmental factors, as well as in sales potentials, make it impractical to set identical expense percentages for all territories. Then, too, different sales personnel sell different product mixes, so some incur higher expenses than others, again making impractical the setting of identical expense percentages. But most important is that selling expense does not vary directly with sales volume, as is implicitly assumed with the expense percentage target. Requiring that !See Chapter 14 expenses vary proportionately with changes in sales volume may reduce selling incentive. It may happen, for instance, that selling expenses amount to 3 percent of sales up to $700,000 in sales, but obtaining an additional $50,000 in sales requires increased expenses of $2,500, which amounts to 5 percent of the marginal sales increase.

Clearly, management should not arbitrarily set percentage expense targets. Analysis of territorial differences, product mixes in individual sales, and expense variations at various sales volume levels should precede actual target setting. Furthermore, because of difficulties in making precise adjustments for these factors, and because of possible changes in territorial conditions during the operating period, administering an expense target system calls for great flexibility.

The chief attraction of the expense target is that it makes sales personnel more cost conscious and aware of their responsibilities towards expense control. They are less apt to regard expense accounts as “swindle sheets” or vehicles for padding take-home pay. Instead, they look upon the expense target as a standard used in evaluating their performance.

However, unless expense targets are intelligently administered, sales personnel may become too cost conscious—they may stay at third-class hotels, patronize third-class restaurants, and avoid entertaining customers. Sales personnel should understand that, although expense money is not to be wasted, they are expected to make all reasonable expenditures. Well-managed companies, in fact, expect sales personnel to maintain standards of living in keeping with those of their customers.

Gross margin or net profit targets. Companies not setting sales volume targets often use gross margin or net profit targets, shifting the emphasis to making gross margin or profit contributions. The rationale is that sales personnel operate more efficiently if they recognize that sales increases, expense reductions, or both, are important only if increased margins and profits result.

Gross margin or net profit targets are appropriate when the product line contains both high- and low-margin items. In this situation, an equal volume increase in each of the two products may have widely different effects upon margins and profits. Low-margin items are the easiest to sell; thus sales personnel taking the path of least resistance concentrate on them and give inadequate attention to more profitable products. One way to obtain better balanced sales mixtures is through gross margin or net profit targets. However, the same results are achieved by setting individual sales volume targets for different products, adjusting each quota to obtain the desired contributions.

Problems are met both in setting and administering gross margin or net profit targets. If gross margin targets are used, management must face the fact that sales personnel generally do not set prices and have no control over manufacturing costs; therefore, they are not responsible for gross margins. If net profit targets are used, management must recognize that certain selling expenses, such as those of operating a branch office, are beyond the salesperson’s influence.

To overcome these complications, companies frequently set targets in terms of “expected contribution” margins, thus avoiding arbitrary allocations of expenses that are not under the control of sales personnel. Arriving at expected contribution margins for each salesperson, however, is complicated. Even if a company solves these accounting-type problems, it faces further problems in administration. Sales personnel may have difficulties in grasping technical features of quota-setting procedures, and management may spend considerable time in ironing out misunderstandings. In addition, special records must be maintained to gather the needed performance information. Finally, because some expense factors are always beyond the control of sales personnel, arguments and disputes are inevitable. The company using gross margin or net profit targets assumes increased clerical and administrative costs.

4. Activity Targets

The desire to control how sales personnel allocate their time and efforts among different activities explains the use of activity targets. A company using activity targets starts by defining the important activities sales personnel perform; then it sets target performance frequencies. Activity targets are set for total sales calls, calls on particular classes of customers, calls on prospects, number of new accounts, missionary calls, product demonstrations, placement or erection of displays, making of collections and the like. Before setting activity targets, management needs time-and-duty studies of how sales personnel actually apportion their time, making additional studies to determine how sales personnel should allocate their efforts. Ideally, management needs time-and-duty studies for every salesperson and sales territory, but, of course, this is seldom practical.

Activity targets are appropriate when sales personnel perform important nonselling activities. For example, activity targets are much used in insurance selling, where sales personnel must continually develop new contacts. They are also common in drug detail selling, where sales personnel call on doctors and hospitals to explain new products and new applications of both old and new products. Activity targets permit management not only to control but to give recognition to sales personnel for performing nonselling activities and for maintaining contacts with customers who may buy infrequently, but in substantial amounts.

While there is a large amount of clerical and record-keeping work, the main problem in administering an activity target system is that of inspiring the sales force. The danger is that sales personnel will merely go through the motions and not perform activities effectively. Activity targets used in isolation reward sales personnel for quantity of work, irrespective of quality. This is less likely to happen when activity targets are used with sales volume or expense targets; still adequate supervision and close contact with sales personnel are administrative necessities.

5. Combination and Other Point System Targets

Combination targets control performance of both selling and nonselling activities. These targets overcome the difficulty of using different measurement units to appraise different aspects of performance (for example, dollars to measure attention given to developing new business). Because performances against combination targets are computed as percentages, these targets are known as point systems, the points being percentage points.

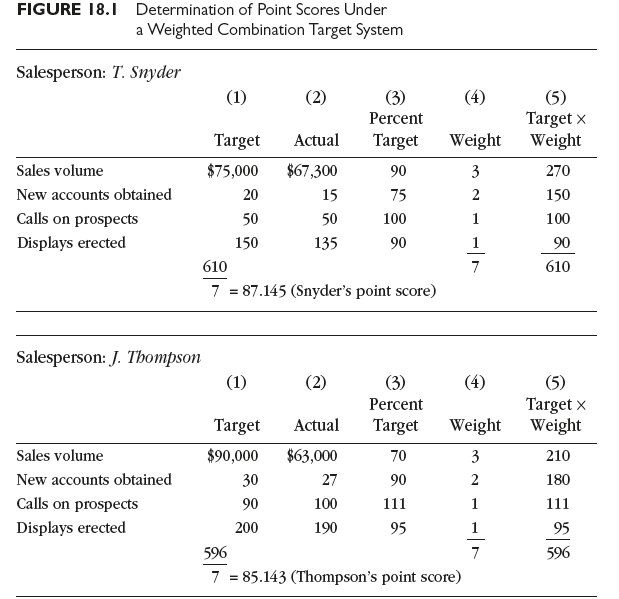

Figure 18.1 illustrates how performances, or point scores, are determined under a system incorporating both sales volume and activity goals. In this system, each of four different aspects of the sales job is weighted according to management’s evaluation of its relative importance. Column 1 shows the four targets making up the combination, and column 2 records actual performance data. Column 3, indicating the percentage of target achieved, is multiplied by the weighting factor in column 4 to yield the weighted performance in column 5. Finally, the column 5 total is divided by the column 4 total to determine each salesperson’s overall performance rating. Thus, Snyder’s rating is 87.145 percentage points (that is, 87.145 percent of the combination target) and Thompson’s is 85.143. Combination targets may also be designed without attaching different weights to the various components (which, of course, is the same as equally weighting all components), but in most cases, different weights are justified because all components are rarely of equal importance. In the example, had different weights not been used, management would have appraised Thompson’s performance as better than Snyder’s: 91 versus 88 percentage points. The reversal emphasizes the importance of selecting weights with care.

Combination targets summarize overall performance in a single measure, but they present some problems. Sales personnel may have difficulties in understanding them and in appraising their own achievements. Combination targets also have a built-in weakness in that design imperfections may cause sales personnel to place too much emphasis on one component activity. Suppose that Snyder or Thompson, in the previous illustration, decides to erect twice as many displays as the target specifies and to do almost no prospecting. The possibility that some sales personnel may try to “beat the system” in this or other ways indicates that, as with other complex target systems, continual supervision of the sales force is essential.

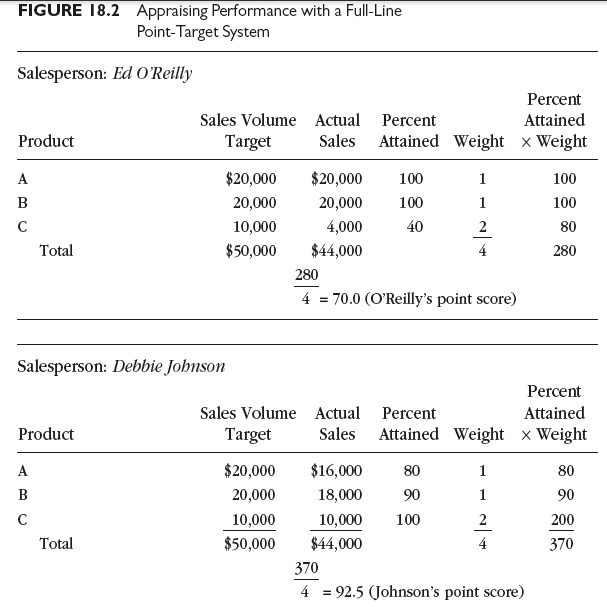

Another widely used point system is the full-line target, which is designed to secure some desired balance of sales among various products. Figure 18.2 illustrates a point system target. Two members of the sales staff, Ed O’Reilly and Debbie Johnson, sell three products, A, B, and C. Products A and B are low-margin items and easy to sell; product C is a high-margin item that takes extra effort to sell. Sales management has set a target for each product and established weights reflecting relative sales difficulty and profitability. By some coincidence, perhaps unrealistic but revealing, O’Reilly and Johnson were assigned identical targets and, by an even greater coincidence, their performances resulted in equal sales volumes. However, Johnson receives the higher point score and therefore is the better performer. Why? She places more emphasis on selling product C and obtains a better balance in selling the three products.

Source: Richard R. Still, Edward W. Cundliff, Normal A. P Govoni, Sandeep Puri (2017), Sales and Distribution Management: Decisions, Strategies, and Cases, Pearson; Sixth edition.

I am typically to blogging and i actually respect your content. The article has actually peaks my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and hold checking for brand new information.

There may be noticeably a bundle to find out about this. I assume you made sure nice factors in features also.