Data gathering and analysis should not be regarded as a one-shot resolution of a single retailing issue. They should be part of an ongoing, integrated process. A retail information system (RIS) anticipates the information needs of retail managers; collects, organizes, and stores relevant data on a continuous basis; and directs the flow of information to the proper decision makers.

These topics are covered next: Building and using a retail information system, database management, and gathering information via the UPC (Universal Product Code) and EDI (electronic data interchange).

1. Building and Using a Retail Information System

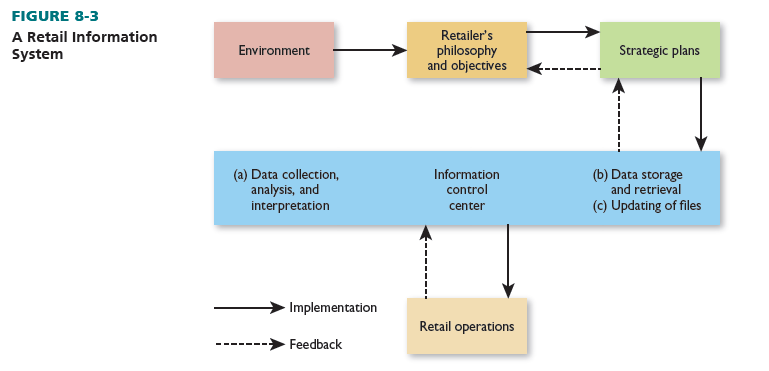

Figure 8-3 presents a general RIS. A retailer begins with its business philosophy and goals, which are affected by environmental factors (such as competitors and the economy). The philosophy and goals provide guidelines that direct strategic planning. Some aspects of plans are routine and need little re-evaluation. Others are nonroutine and need evaluation each time they arise.

After a strategy is outlined, data must be collected, analyzed, and interpreted. If data already exist, they are retrieved from files. When new data are acquired, files are updated. All of this occurs in the information control center. Based on data in the control center, decisions are enacted.

Performance is fed back to the information control center and compared with pre-set criteria. Data are retrieved from files or further data collected. Routine adjustments are made promptly. Regular reports and exception reports (to explain deviations from expected performance) are shown to the right parties. Managers may react in a way affecting company philosophy or goals (such as revamping a passe image or forgoing short-run profits to buy a new computer system).

All types of data should be stored in the control center for future and ongoing use, and the control center should be integrated with the firm’s short- and long-run plans and operations. Information should not be gathered sporadically and haphazardly but systematically.

A good RIS has several strengths. Information gathering is organized and company focused. Data are regularly collected and stored so opportunities are foreseen and crises averted. Strategic elements can be coordinated. New strategies can be devised more quickly. Quantitative results are accessible, and cost/benefit analysis can be done. Information is routed to the right personnel. Yet, deploying a retail information system may require high initial time and labor costs, and complex decisions may be needed to set up such a system.

In building a retail information system, a number of decisions have to be made:

- How active a role should be given to the RIS? Will it be used to proactively search for and distribute any relevant data or will it be used to reactively respond to requests from managers when problems arise? The best systems are more proactive because they anticipate events.

- Should an RIS be managed internally or be outsourced? Although many retailers engage in RIS functions, some use outside specialists. Either style can work, so long as the RIS is guided by the retailer’s information needs. Several firms have their own RIS and use outside firms for specific tasks (such as conducting surveys or managing networks).

- How much should an RIS cost? Retailers typically spend 0.5 to 2.5 percent of their sales on an RIS. This lags behind most of the suppliers from which retailers buy goods and services.5

- How technology-driven should an RIS be? Although retailers can gather data from trade associations, surveys, and so forth, more firms now rely on technology to drive the information process. With the advent of low-cost personal computers and tablets, inexpensive networks, cloud computing, and low-priced software, technology is easy to use. Even a neighborhood deli can generate sales data by product and offer specials on slow-sellers. See Figure 8-4.

- How much data are enough? The purpose of an RIS is to provide enough information, on a regular basis, for a retailer to make the proper strategy choices—not to overwhelm retail managers. This means performing a balancing act between too little information and information overload. To avoid overload, data should be carefully edited to eliminate redundancies.

- How should data be disseminated throughout the firm? This requires decisions as to who receives various reports, frequency of data distribution, and access to databases. When a firm has multiple divisions or operates in several regions, information access and distribution must be coordinated.

- How should data be stored for future use? Relevant data should be stored in a way that makes information retrieval easy and allows for adequate longitudinal (period-to-period) analysis.

Larger retailers tend to have a chief information officer (CIO) oversee the RIS. Their information systems departments often have formal, written annual plans. Computers are used by virtually all firms that conduct information systems analysis, and many firms use the Web for some RIS functions. Further growth in the use of retail information systems is still expected. There are many differences in information systems among retailers, in terms of revenues and retail format.

Thirty-five years ago, most computerized retail systems were used only to reduce cashier errors and improve inventory control. Today, they often form the basis for a retail information system and are used in surveys, ordering, merchandise transfers between stores, and other tasks. These activities are conducted by both small and large retailers. Most small and medium retailers—as well as large retailers—have computerized financial management systems, analyze sales electronically, and use computerized inventory management systems. Here are illustrations of how retailers are using the latest technology advances to computerize their information systems.

Retail Pro, Inc. markets Retail Pro management information software to retailers. This software is used at stores around the world. Although popular with large retailers, Retail Pro software also appeals to smaller and specialty retailers due to flexible pricing based on the number of users and stores, the type of hardware, payment fraud protection with its partner Cayan POS, customer personalization, and business optimization technology for an omnichannel strategy.6

MicroStrategy typically works with larger retailers—including about two-thirds of the top 500 retailers in the world—to provide merchandising optimization, loss prevention, and customer insight analytics; mobile technology for customer engagement; sales training; product information; and store operations and security solutions.7

2. Database Management

In database management, a retailer gathers, integrates, applies, and stores information related to specific subject areas. It is a major element in a retail information system, and may be used with customer databases, vendor databases, product category databases, and so on. A firm may compile and store data on customer attributes and purchase behavior, compute sales figures by vendor, and store records by product category. Each of these would represent a separate database. Among retailers that have databases, most use them for frequent shopper programs, customer analysis, promotion evaluation, inventory planning, trading-area analysis, joint promotions with manufacturers, media planning, and customer communications.

Database management should be approached as a series of five steps:

- Plan the particular database and its components and determine information needs.

- Acquire the necessary information.

- Retain the information in a usable and accessible format.

- Update the database regularly to reflect demographic trends, recent purchases, and so forth.

- Analyze the database to determine company strengths and weaknesses.

Information can come from internal and external sources. A firm can develop databases internally by keeping detailed records and sorting them. It could generate databases by customer— purchase frequency, items bought, average purchase, demographics, and payment method; by vendor—total retailer purchases per period, total sales to customers per period, the most popular items, retailer profit margins, delivery time, and service quality; and by product category—total category sales per period, item sales per period, retailer profit margins, and the percentage of items discounted.

As retailers align their strategies around customer needs and experiences across multiple channels, the need to extract and integrate high-quality, context-specific information from the big data deluge is paramount. Customer information management providers such as Pitney Bowes, a leader in this field, leverage their expertise and data collected from their multiple clients and industries to facilitate cross-channel and cross-border commerce. Pitney Bowes’ Single Customer View service provides a fully integrated 360-degree view of customers to employees. This is done by converting company-dispersed customer interaction data into integrated databases; adding geodemographic context to customer profiles to uncover timely, actionable insights to help craft memorable customer experiences; dynamically tracking customer lifetime value; improving the efficiency of customer acquisitions; and, in some cases, ensuring compliance with national and international regulations.8

To effectively manage a retail database, these are vital considerations:

- What are the firm’s database goals?

- Who will be responsible for data management?

- What type of information will be collected and produced? What will be its format (images, data files, and so on)? Where do you plan to store the data?

- Is every database initiative analyzed to see if it is successful?

- Is there a mechanism to flag data that indicates potential problems or opportunities?

- Are customer purchases of different items or from different company divisions cross-linked?

- How will data be communicated?

- Is there a clear privacy policy that is communicated to those in a database? Are there opt-out provisions for those who do not want to be included in a database?

- Is the database updated each time there is a customer interaction?

- Are customers, personnel, suppliers, and others invited to update their personal data?

- Is the database periodically checked to eliminate redundant files?

- Roughly how long should the data be retained? Is it permanent? Will it be updated?9

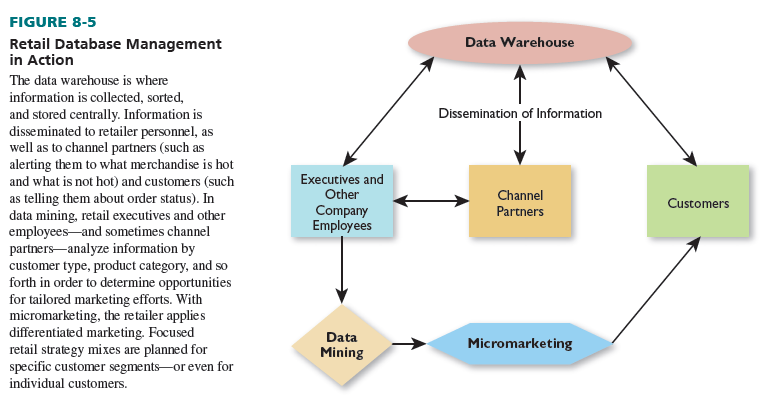

Let’s now discuss two aspects of database management: Data warehousing is a mechanism for storing and distributing information. Data mining and micromarketing are ways in which information can be utilized. Figure 8-5 shows the interplay of data warehousing with data mining and micromarketing.

DATA WAREHOUSING One advance in database management is data warehousing, whereby copies of all the databases in a firm are maintained in one location and are accessible to employees at any locale. A data warehouse is a comprehensive compilation of the data used to support management decision making. According to government sources,

The fundamental attributes of a data warehouse are: Subject-Oriented—A data warehouse is organized around high-level business groupings called subjects [such as sales]. Integrated—The data in the warehouse must be integrated and consistent. If two different source systems store conflicting data, the differences need to be resolved during the process of transforming the source data and loading it into the data warehouse. Time-Variant—A key characteristic distinguishing warehouses is the currency of the data. Operational systems require real-time views of data, while data warehouse applications generally deal with longer term, historical data. They can also provide access to a greater volume of more detailed information over a longer time period. Nonvolatile—Data in the warehouse is readonly; updates or a refresh of the data occur on a periodic incremental or full refresh basis.10

A data warehouse has these components: (1) the data warehouse, where data are actually stored; (2) software to copy original databases and transfer them to the warehouse; (3) interactive software to process queries; and (4) a directory for the categories of data kept in the warehouse.

Data warehousing has several advantages. Executives and other employees are quickly, easily, and simultaneously able to access data wherever they may be. There is more companywide entree to new data when they are first available. Data inconsistencies are reduced by consolidating records in one location. Better data analysis and manipulation are possible because information is stored in one location.

Computerized data warehouses were once costly to build (an average of $2.2 million in the 1990s) and, thus, feasible only for the largest retailers. Rapid progress in Web 2.0 and cloud technologies now makes it possible for startup businesses, especially online-only retailers, to access data warehouse as a service (DWaaS). It is a cloud-based outsourcing model in which DWaaS service providers such as Google (BigQuery), Microsoft (Azure), and Amazon Web Services (AWS) configure and manage the hardware, software platforms, and resources a data warehouse requires. The small business user uploads its own data and queries it on the Web through application programming interfaces (APIs), and pays based on usage for the managed service.11 The user has no upfront costs to create, staff to manage, or software or hardware to upgrade, and can easily and quickly scale up from small to large in terms of usage and storage. Oracle, NCR-Teradata, and IBM provide enterprise-level data warehousing, and DWaaS provides the same to mid-size and large firms. Cabela’s, Hudson’s Bay, and 7-Eleven are just a few of the multitude of retailers that use data warehousing.12

Dollar Tree’s Family Dollar (www.familydollar.com) discount stores is one of the retailers positioning itself for long-term growth and developing an efficient collaborative business intelligence program with suppliers by using a constantly updated retail data warehousing structure developed by Retail Solutions (RSi, www.retailsolutions.com). Real-time store-level inventory and point-of-sale data at the store/item and category level are provided through a Retail Management Solution after cleansing, validation, and standardization through a single portal to Family Dollar and its suppliers. Family Dollar can analyze performance by store cluster, price point, and product mix, and identify lost sales opportunities. Suppliers can fine-tune forecasting and product allocations, and identify distribution voids (e.g., phantom inventory). The micro-level information provides suppliers with greater understanding of consumer demand. Increased collaboration with Family Dollar lowers inventory-holding costs while providing consumers with the highest service levels.13

DATA MINING AND MICROMARKETING Data mining is the in-depth analysis of information to gain specific insights about customers, product categories, vendors, and so forth. The goal is to learn if there are opportunities for tailored marketing efforts that would lead to better retailer performance. One application of data mining is micromarketing, whereby the retailer uses differentiated marketing and develops focused retail strategy mixes for specific customer segments, sometimes fine-tuned for the individual shopper.

Data mining relies on special software to sift through a data warehouse to uncover patterns and relationships among different factors. The software allows vast amounts of data to be quickly searched and sorted. That is why many firms, such as supermarkets, have made the financial commitment to data mining. The entry of well-funded online players such as Amazon, Google, and others has made the competition for grocery share of wallet even more fierce. Grocery has a distinct advantage over other forms of retail to leverage predictive analytics because consumers typically make frequent shopping trips according to SAS, a provider of business analytics software and services. Frequent-shopper card data help grocers track customer purchases over time and understand a shopper’s evolving buying behavior. By using behavioral analytics and value segmentation for multiple shoppers within a single household, combined with demographic data, retailers can create a more complete picture of that household’s needs and habits, personalize the shopping experience with micro-targeted promotions to increase the amount of groceries purchased, improve profit margins, and increase consumer satisfaction.14

3. Gathering Information through the UPC and EDI

To be more efficient with their information systems, most retailers rely on the Universal Product Code (UPC) and many now utilize electronic data interchange (EDI).

With the Universal Product Code (UPC), products (or tags attached to them) are marked with a series of thick and thin vertical lines, representing each item’s identification code. An item’s UPC includes both numbers and lines. The lines are “read” by scanners at checkout counters. Cashiers do not enter transactions manually—though they can, if needed. Because the UPC itself is not readable by humans, the retailer or vendor must attach a ticket or sticker to a product specifying its size, color, and other information (if not on the package or the product). Given that the UPC does not include price information, this too must be added by a ticket or sticker.

By using UPC-based technology, retailers can record data instantly on an item’s model number, size, color, and other factors when it is sold, as well as send the data to a computer that monitors unit sales, inventory levels, and so forth. The goals are to produce better merchandising data, improve inventory management, speed transaction time, raise productivity, reduce errors, and coordinate information.

Since its inception more than 40 years ago, UPC technology has improved substantially. It is now the accepted retailing standard. Several billion scans occur every day. The UPC allows all stores in the retail sector to identify products and capture information about them. Stores can control inventory more efficiently, provide a faster and more accurate checkout for customers, and easily gather inventory data for accurate and immediate marketing reports. Virtually every time sales or inventory data are scanned by a computer, UPC technology is involved. More than 200,000 U.S. manufacturers and retailers belong to GS1 US (formerly known as the Uniform Code Council), a group that has taken the lead in setting and promoting inter-industry product identification and communication standards.15 Figure 8-6 shows how far UPC technology has come.

Regular UPC tags may result in errors when scanned by customers for product information lookup and be a disadvantage in mobile commerce. To meet the needs of mobile-centric customers, manufacturers and brand owners are adopting GS1 US Mobile Scan that imprints packages with an imperceptible digital watermark (DWcode), that, when scanned with a smartphone app, is linked to a mobile-optimized Web address. This provides contextual product information provided by the brand. Retailers benefit from faster retail checkout, better supply chain efficiency, and an enhanced in-store experience resulting from more information at product locations in aisles and inventory. Consumers, anywhere in the world, get information transparency by scanning the UPC or package imprinted with a DWcode with their Internet-enabled smartphones. Consumers are then able to see a Web page with real-time, brand-authorized product information, pricing, special offers, instructional videos, rich media, and additional shopping assistance.16

With electronic data interchange (EDI) and Internet electronic data interchange (I-EDI), retailers and suppliers regularly exchange information through their computers with regard to inventory levels, delivery times, unit sales, and so on of particular items. As a result, both parties enhance their decision-making capabilities, better control inventory, and are more responsive to demand. UPC scanning is often the basis for product-related EDI data. Hundreds of thousands of firms around the world (led by U.S.-based firms) use some form of the EDI system. Retailers use EDI to replace paper-based documents such as purchase orders, invoices, inventory reports, shipping notifications, routing requests, and routing instructions to electronic documents sent from one computer system to another instantaneously.

Unlike in some other industries, the supply chain in the retail industry is very complicated, and has to be flexible and responsive to fluctuations in demand levels, which can differ for each SKU (stock-keeping unit); and the number of SKUs may increase each year. A retail supply chain cannot afford occasional order delays or “stock-outs”; this it leads to lost sales and raises the risk of sending customers to the competition. Vendor-managed inventory (VMI) systems, one of EDI’s applications, shorten the replenishment cycle and ensure that accurate and timely information is passed on electronically at every stage of the fulfillment cycle by streamlining direct store delivery and lowering delivery and labor costs. This ensures that customers always get products when they want them (e.g., during promotion events or holidays when demand is very high), yet reduces oversupply when demand wanes. Vendor-managed inventory helps retailers strengthen relationships with customers and vendors by reducing check-in times, keeping products stocked consistently, and reducing human errors.17

Many retailers now require potential suppliers to have an EDI solution—either their own or via a third-party provider—before they are selected (“onboarded”) as a vendor. Many small and medium-sized suppliers and retailers choose cloud-based, third-party EDI solutions for more flexibility and faster integration, quicker onboarding of suppliers, reduction of operating costs, elimination of manual ordering, and better order management.18 The EDI system is covered further in Chapter 15, along with collaborative planning, forecasting, and replenishment.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

I have read some good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to make such a fantastic informative site.