Ultimately, marketing is the art of attracting and keeping profitable customers. Yet every company loses money on some of its customers. The well-known 80-20 rule states that 80 percent or more of the company’s profits come from the top 20 percent of its customers. Some cases may be more extreme—the most profitable 20 percent of customers (on a per capita basis) may contribute as much as 150 to 300 percent of profitability. The least profitable 10 to 20 percent, on the other hand, can actually reduce profits between 50 and 200 percent per account, with the middle 60 to 70 percent breaking even.29 The implication is that a company could improve its profits by “firing” its worst customers.

Companies need to concern themselves with Return on Customer (ROC) and how efficiently they create value from the customers and prospects available.30 It’s not always the company’s largest customers who demand considerable service and deep discounts or who yield the most profit. The smallest customers pay full price and receive minimal service, but the costs of transacting with them can reduce their profitability. Midsize customers who receive good service and pay nearly full price are often the most profitable.

1. CUSTOMER PROFITABILITY

A profitable customer is a person, household, or company that over time yields a revenue stream exceeding by an acceptable amount the company’s cost stream for attracting, selling, and serving that customer. Note the emphasis is on the lifetime stream of revenue and cost, not the profit from a particular transaction.31 Marketers can assess customer profitability individually, by market segment, or by channel.

Many companies measure customer satisfaction, but few measure individual customer profitability.32 Banks claim this is a difficult task because each customer uses different banking services and the transactions are logged in different departments. However, the number of unprofitable customers in their customer database has appalled banks that have succeeded in linking customer transactions. Some report losing money on more than 45 percent of their retail customers.

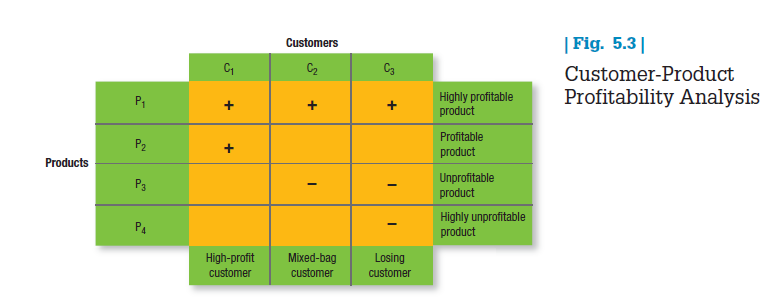

CUSTOMER PROFITABILITY ANALYSIS A useful type of profitability analysis is shown in Figure 5.3.33 Customers are arrayed along the columns and products along the rows. Each cell contains a symbol representing the profitability of selling that product to that customer. Customer 1 is very profitable; he buys two profit-making products (P1 and P2). Customer 2 yields mixed profitability; she buys one profitable product (P1) and one unprofitable product (P3). Customer 3 is a losing customer because he buys one profitable product (P1) and two unprofitable products (P3 and P4).

What can the company do about customers 2 and 3? (1) It can raise the price of its less profitable products or eliminate them, or (2) it can try to sell customers 2 and 3 its profit-making products. Unprofitable customers who defect should not concern the company. In fact, the company should encourage them to switch to competitors.

Customer profitability analysis (CPA) is best conducted with the tools of an accounting technique called activity-based costing (ABC). ABC accounting tries to identify the real costs associated with serving each customer—the costs of products and services based on the resources they consume. The company estimates all revenue coming from the customer, less all costs.

With ABC, the costs in a business-to-business setting should include the cost not only of making and distributing the products and services but also of taking phone calls from the customer, traveling to visit the customer, paying for entertainment and gifts—all the company’s resources that go into serving that customer. ABC also allocates indirect costs like clerical costs, office expenses, supplies, and so on, to the activities that use them, rather than in some proportion to direct costs. Both variable and overhead costs are tagged back to each customer.

Companies that fail to measure their costs correctly are also not measuring their profit correctly and are likely to misallocate their marketing effort. The key to effectively employing ABC is to define and judge “activities” properly. One time-based solution calculates the cost of one minute of overhead and then decides how much of this cost each activity uses.34

2. MEASURING CUSTOMER LIFETIME VALUE

The case for maximizing long-term customer profitability is captured in the concept of customer lifetime value.35 Customer lifetime value (CLV) describes the net present value of the stream of future profits expected over the customer’s lifetime purchases. The company must subtract from its expected revenues the expected costs of attracting, selling, and servicing the account of that customer, applying the appropriate discount rate (say, between 10 and 20 percent, depending on cost of capital and risk attitudes). Lifetime value calculations for a product or service can add up to tens of thousands of dollars or even run to six figures.36

Many methods exist to measure CLV.37 “Marketing Memo: Calculating Customer Lifetime Value” illustrates one. CLV calculations provide a formal quantitative framework for planning customer investment and help marketers adopt a long-term perspective. One challenge, however, is to arrive at reliable cost and revenue estimates. Marketers who use CLV concepts must also take into account the short-term, brand-building marketing activities that help increase customer loyalty. One firm that has excelled in taking a short-run and long-run view of customer loyalty is Harrah’s.38

HARRAH’S Harrah’s Entertainment, led by one-time academic Gary Loveman, has gone in a different direction from the big players in the Las Vegas gaming industry whose business models are based on building bigger and more opulent casinos. Back in 1997, Harrah’s launched a pioneering loyalty program that pulled all customer data into a centralized warehouse and then ran sophisticated analyses to better understand the value of the investments the casino made in its customers. Harrah’s has more than 40 million active members in its Total Rewards loyalty program, a system it has fine- tuned to achieve near-real-time analysis: As customers interact with slot machines, check into casinos, or buy meals, they receive reward offers—food vouchers or gambling credits, for example—based on predictive analyses from its database. Harrah’s spends $100 million a year on information technology. The company has now identified hundreds of highly specific customer segments, and by targeting offers to each of them, it can almost double its share of customers’ gaming budgets and generate $6.4 billion annually (80 percent of its gaming revenue). Research has shown that contrary to conventional wisdom, the most profitable customers are not the jet-setting high rollers, but older slot machine players. Harrah’s also learned to dramatically cut back on its traditional ad spending, largely replacing it with direct mail and e-mail—a good customer may receive as many as 150 pieces in a year. Harrah’s also rewards staff and bases compensation in part on customer service scores. To better fine-tune its Web sites and online ads, Harrah’s monitors customer reviews and comments on TripAdvisor.com as well as social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook. After the company made changes to reflect customer interest in hotel amenities and the iconic views of the Las Vegas strip from its Paris Las Vegas hotel and casino, online bookings increased by double digits. Data from the Total Rewards program even influenced Harrah’s decision to buy Caesars Entertainment, when company research revealed that most of Harrah’s customers who visited Las Vegas without staying at a Harrah’s-owned hotel were going to Caesars Palace. Harrah’s latest loyalty innovation is a mobile marketing program that sends time-based and location-based offers to customers’ mobile devices in real time.

3. ATTRACTING AND RETAINING CUSTOMERS

Companies seeking to expand profits and sales must invest time and resources searching for new customers. To generate leads, they advertise in media that will reach new prospects, send direct mail and e-mails to possible new prospects, send their salespeople to participate in trade shows where they might find new leads, purchase names from list brokers, and so on.

Different acquisition methods yield customers with varying CLVs. One study showed that customers acquired through the offer of a 35 percent discount had about one-half the long-term value of customers acquired without any discount.39 Many of these customers were more interested in the offer than in the product itself.

Similarly, many local restaurants, car wash services, beauty salons, and dry cleaners have launched “daily deal” campaigns from Groupon and LivingSocial to attract new customers. Unfortunately, these campaigns have sometimes turned out to be unprofitable in the long run because coupon users were not easily converted into loyal customers.40

Harrah’s uses sophisticated customer analytics to guide its marketing activities, including filling rooms in its Paris Las Vegas hotel and casino.

Promotional campaigns that reinforce the value of the brand, even if targeted to the already loyal, may be more likely to attract higher-value new customers. Two-thirds of the considerable growth spurred by UK mobile communication leader O2’s loyalty strategy was attributed to recruitment of new customers; the remainder came from reduced defection.

REDUCING DEFECTION It is not enough to attract new customers; the company must also keep them and increase their business.42 Too many companies suffer from high customer churn or defection. Adding customers here is like adding water to a leaking bucket.

Cellular carriers and cable TV operators are plagued by “spinners,” customers who switch carriers at least three times a year looking for the best deal. Many carriers lose 25 percent of their subscribers each year, at an estimated cost of $2 billion to $4 billion. Defecting customers cite unmet needs and expectations, poor product/service quality and high complexity, and billing errors.43

To reduce the defection rate, the company must:

- Define and measure its retention rate. For a magazine, subscription renewal rate is a good measure of retention. For a college, it could be first- to second-year retention rate or class graduation rate.

- Distinguish the causes of customer attrition and identify those that can be managed better. Not much can be done about customers who leave the region or go out of business, but poor service, shoddy products, and high prices can all be addressed.44

- Compare the lost customer’s lifetime value to the costs of reducing the defection rate. As long as the cost to discourage defection is lower than the lost profit, spend the money to try to retain the customer.

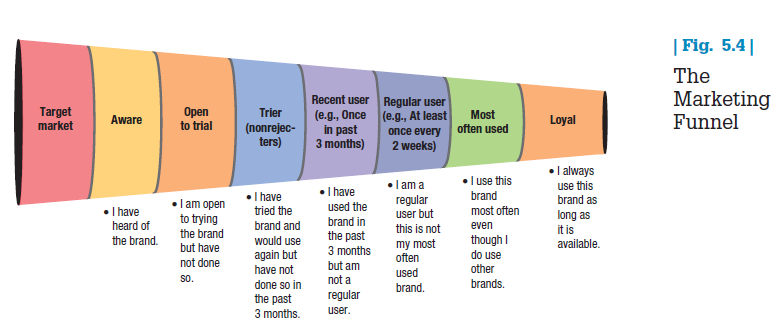

RETENTION DYNAMICS Figure 5.4 shows the main steps in attracting and retaining customers, imagined in terms of a funnel, and some sample questions to measure customer progress through the funnel. The marketing funnel identifies the percentage of the potential target market at each stage in the decision process, from merely aware to highly loyal. Consumers must move through each stage before becoming loyal customers. Some marketers extend the funnel to include loyal customers who are brand advocates or even partners with the firm.

By calculating conversion rates—the percentage of customers at one stage who move to the next—the funnel allows marketers to identify any bottleneck stage or barrier to building a loyal customer franchise. If the percentage of recent users is significantly lower than triers, for instance, something might be wrong with the product or service that prevents repeat buying.

The funnel also emphasizes how important it is not just to attract new customers but to retain and cultivate existing ones. Satisfied customers are the company’s customer relationship capital. If the company were sold, the acquiring company would pay not only for the plant and equipment and brand name but also for the delivered customer base, the number and value of customers who will do business with the new firm. Consider these data about customer retention:45

- Acquiring new customers can cost five times more than satisfying and retaining current ones. It requires a great deal of effort to induce satisfied customers to switch from their current suppliers.

- The average company loses 10 percent of its customers each year.

- A 5 percent reduction in the customer defection rate can increase profits by 25 percent to 85 percent, depending on the industry.

- Profit rate tends to increase over the life of the retained customer due to increased purchases, referrals, price premiums, and reduced operating costs to service.

MANAGING THE CUSTOMER BASE Customer profitability analysis and the marketing funnel help marketers decide how to manage groups of customers that vary in loyalty, profitability, risk, and other factors. A key driver of shareholder value is the aggregate value of the customer base. Winning companies improve that value by excelling at strategies like the following:

- Reducing the rate of customer defection. Selecting and training employees to be knowledgeable and friendly increases the likelihood that customers’ shopping questions will be answered satisfactorily. Whole Foods, the world’s largest retailer of natural and organic foods, woos customers with a commitment to market the best foods and a team concept for employees.

- Increasing the longevity of the customer relationship. The more engaged with the company, the more likely a customer is to stick around. Nearly 65 percent of new Honda purchases replace an older Honda. Drivers cited Honda’s reputation for creating safe vehicles with high resale value. Seeking consumer advice can be an effective way to engage consumers with a brand and company.47

- Enhancing the growth potential of each customer through “share of wallet,” cross-selling, and up- selling.48 Sales from existing customers can be increased with new offerings and opportunities. Harley- Davidson sells more than motorcycles and accessories like gloves, leather jackets, helmets, and sunglasses. Its dealerships sell more than 3,000 items of clothing—some even have fitting rooms. Licensed goods sold by others range from predictable items (shot glasses, cue balls, and Zippo cigarette lighters) to the more surprising (cologne, dolls, and cell phones). Cross-selling isn’t profitable if the targeted customer requires a lot of services for each product, generates a lot of product returns, cherry-picks promotions, or limits total spending across all products.49

- Making low-profit customers more profitable or terminating them. To avoid trying to terminate them, marketers can instead encourage unprofitable customers to buy more or in larger quantities, forgo certain features or services, or pay higher amounts or fees.50 Banks, phone companies, and travel agencies all now charge for once-free services to ensure minimum revenue levels from these customers. Firms can also discourage those with questionable profitability prospects. Progressive Insurance screens customers and diverts the potentially unprofitable to competitors.51 However, “free” customers who pay little or nothing and are subsidized by paying customers—as in print and online media, employment and dating services, and shopping malls—may still create useful direct and indirect network effects, an important function.52

- Focusing disproportionate effort on high-profit customers. The most profitable customers can be treated in a special way. Thoughtful gestures such as birthday greetings, small gifts, or invitations to special sports or arts events can send them a strong positive signal.

4. MARKETING MEMO Calculating Customer Lifetime Value

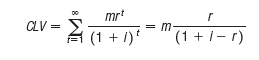

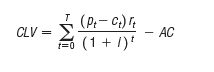

Researchers and practitioners have used many different approaches for modeling and estimating CLV. Columbia’s Don Lehmann and Harvard’s Sunil Gupta recommend the following formula to estimate the CLV for a not-yet-acquired customer:

Where

pt = price paid by a consumer at time t,

ct = direct cost of servicing the customer at time t,

i = discount rate or cost of capital for the firm,

rt = probability of customer repeat buying or being “alive” at time t,

AC = acquisition cost, and

T = time horizon for estimating CLV.

A key decision is what time horizon to use for estimating CLV. Typically, three to five years is reasonable. With this information and estimates of other variables, we can calculate CLV using spreadsheet analysis.

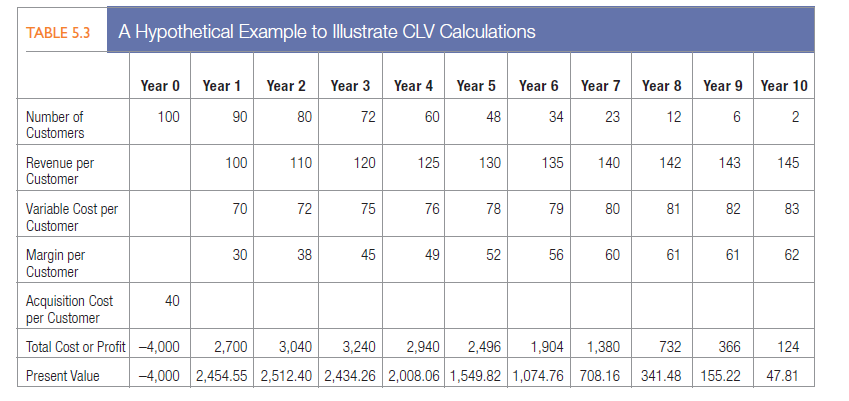

Gupta and Lehmann illustrate their approach by calculating the CLV of 100 customers over a 10-year period (see Table 5.3). In this example, the firm acquires 100 customers with an acquisition cost per customer of $40. Therefore, in year 0, it spends $4,000. Some of these customers defect each year. The present value of the profits from this cohort of customers over 10 years is $13,286.52. The net CLV (after deducting acquisition costs) is $9,286.52, or $92.87 per customer.

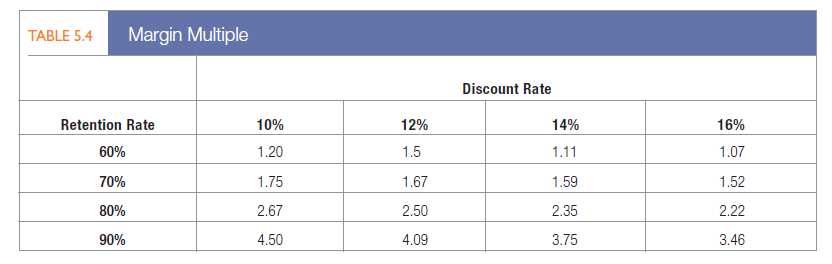

Using an infinite time horizon avoids having to select an arbitrary time horizon for calculating CLV. In the case of an infinite time horizon, if margins (price minus cost) and retention rates stay constant over time, the future CLV of an existing customer simplifies to the following:

In other words, CLV simply becomes margin (m) times a margin multiple [r/(1 + i – r)].

Table 5.4 shows the margin multiple for various combinations of r and i and a simple way to estimate CLV of a customer. When retention rate is 80 percent and discount rate is 12 percent, the margin multiple is about two and a half. Therefore, the future CLV of an existing customer in this scenario is simply his or her annual margin multiplied by 2.5.

Sources: Sunil Gupta and Donald R. Lehmann, “Models of Customer Value,” Berend Wierenga, ed., Handbook of Marketing Decision Models (Berlin, Germany: Springer Science and Business Media, 2007); Sunil Gupta and Donald R. Lehmann, “Customers as Assets,” Journal of Interactive Marketing 17, no. 1 (Winter 2006), pp. 9-24; Sunil Gupta and Donald R. Lehmann, Managing Customers as Investments (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing, 2005); Peter Fader, Bruce Hardie, and Ka Lee, “RFM and CLV: Using Iso-Value Curves for Customer Base Analysis,” Journal of Marketing Research 42, no. 4 (November 2005), pp. 415-30; Sunil Gupta, Donald R. Lehmann, and Jennifer Ames Stuart, “Valuing Customers,” Journal of Marketing Research 41, no. 1 (February 2004), pp. 7-18.

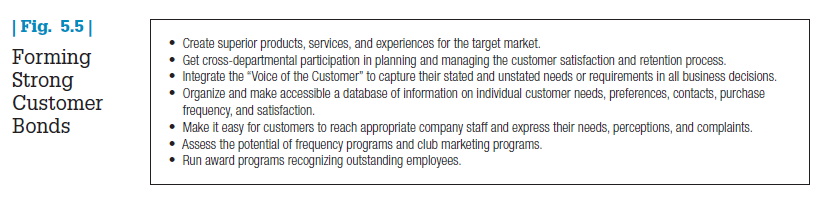

5. BUILDING LOYALTY

Companies that want to form strong, tight connections to customers should heed some specific considerations (see Figure 5.5). One set of researchers sees retention-building activities as adding financial benefits, social benefits, or structural ties.53 Next we describe three marketing activities that improve loyalty and retention.

INTERACT CLOSELY WITH CUSTOMERS Connecting customers, clients, patients, and others directly with company employees is highly motivating and informative. End users can offer tangible proof of the positive impact of the company’s products and services, express appreciation for employee contributions, and elicit empathy. A brief visit from a student who had received a scholarship motivated university fundraisers to increase their weekly productivity by 400 percent; a patient’s photograph inspired radiologists to improve the accuracy of their diagnostic findings by 46 percent.

Listening to customers is crucial to customer relationship management. Some companies have created an ongoing mechanism that keeps their marketers permanently plugged in to frontline customer feedback.

- Deere & Company, which makes John Deere tractors and has a superb record of customer loyalty—nearly 98 percent annual retention in some product areas—has used retired employees to interview defectors and customers.55

- Chicken of the Sea has 80,000 members in its Mermaid Club, a core-customer group that receives special offers, health tips and articles, new product updates, and an informative e-newsletter. In return, club members provide valuable feedback on what the company is doing and thinking of doing. Their input has helped design the brand’s Web site, develop messages for TV advertising, and craft the look and text on the packaging.56

- Build-A-Bear Workshop uses a “Cub Advisory Board” as a feedback and decision-input body. The board is made up of twenty 5- to 16-year-olds who review new-product ideas and give a “paws up or down.” Many products in the stores are customer ideas.57

But listening is only part of the story. It is also important to be a customer advocate and, as much as possible, take the customers’ side and understand their point of view.58

DEVELOP LOYALTY PROGRAMS Frequency programs (FPs) are designed to reward customers who buy frequently and in substantial amounts. They can help build long-term loyalty with high CLV customers, creating cross-selling opportunities in the process. Pioneered by the airlines, hotels, and credit card companies, FPs now exist in many other industries. Most supermarket and drug store chains offer price club cards that grant discounts on certain items.

Typically, the first company to introduce an FP in an industry gains the most benefit, especially if competitors are slow to respond. After competitors react, FPs can become a financial burden to all the offering companies, but some companies are more efficient and creative in managing them. Some FPs generate rewards in a way that locks customers in and creates significant switching costs. FPs can also produce a psychological boost and a feeling of being special and elite that customers value.59

Club membership programs attract and keep those customers responsible for the largest portion of business. Clubs can be open to everyone who purchases a product or service or limited to an affinity group or those willing to pay a small fee. Although open clubs are good for building a database or snagging customers from competitors, limited membership is a more powerful long-term loyalty builder. Fees and membership conditions prevent those with only a fleeting interest in a company’s products from joining.

Apple encourages owners of its computers to form local Apple user groups. There are hundreds of groups, ranging in size from fewer than 30 members to more than 1,000. The groups provide Apple owners with opportunities to learn more about their computers, share ideas, and get product discounts. They sponsor special activities and events and perform community service. A visit to Apple’s Web site will help a customer find a nearby user group.60

CREATE iNSTiTUTiONAL TIES The company may supply business customers with special equipment or computer links that help them manage orders, payroll, and inventory. Customers are less inclined to switch to another supplier when it means high capital costs, high search costs, or the loss of loyal-customer discounts. McKesson Corporation, a leading pharmaceutical wholesaler, invested millions of dollars in EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) capabilities to help its independent-pharmacy customers manage inventory, order-entry processes, and shelf space. Another example is Milliken & Company, which provides proprietary software programs, marketing research, sales training, and sales leads to loyal customers.

6. BRAND COMMUNITIES

Thanks to the Internet, companies are interested in collaborating with consumers to create value through communities built around brands. A brand community is a specialized community of consumers and employees whose identification and activities focus around the brand.61 Three characteristics identify brand communities:62

- A “consciousness of kind,” or a sense of felt connection to the brand, company, product, or other community members;

- Shared rituals, stories, and traditions that help convey the meaning of the community; and

- A shared moral responsibility or duty to both the community as a whole and individual community members.

TYPES OF BRAND COMMUNITIES Brand communities come in many different forms.63 Some arise organically from brand users, such as the Atlanta MGB riders club and the Porsche Rennlist online discussion group. Others are company-sponsored and facilitated, such as Club Green Kids (official kids’ fan club of the Boston Celtics) and the Harley Owners Group (H.O.G.).64

HARLEY-DAVIDSON Founded in 1903 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Harley-Davidson has twice narrowly escaped bankruptcy but is today one of the most recognized motor vehicle brands in the world. In dire financial straits in the 1980s, Harley licensed its name to such ill-advised ventures as cigarettes and wine coolers. Although consumers loved the brand, sales were depressed by product-quality problems, so Harley began its return to greatness by improving manufacturing processes. It also developed a strong brand community in the form of an inclusive owners’ club, called the Harley Owners Group (H.O.G.), which sponsors bike rallies, charity rides, and other motorcycle events and now numbers more than 1 million members in some 1,400 chapters. H.O.G. benefits include a magazine called Hog Tales, a touring handbook, emergency road service, a specially designed insurance program, theft reward service, discount hotel rates, and a Fly & Ride program enabling members to rent Harleys on vacation. The company also maintains an extensive Web site devoted to H.O.G. with information about club chapters and events and a special members-only section. Harley is active with social media too and boasts more than 3.3 million Facebook fans. One fan inspired a digital video and Twitter campaign dubbed E Pluribus Unum—“Out of Many, One”—where Harley riders from all walks of life show their diversity and their pride in their bikes.

Companies large and small can build brand communities. When New York’s Signature Theatre Company built a new 70,000-square-foot facility for its shows, it made sure there was a central hub where casts, crew, playwrights, and audiences for all productions could mingle and interact.65

Online, marketers can tap into social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs or create their own online community. Members can recommend products, share reviews, create lists of recommendations and favorites, or socialize together online.

Online forums can be especially helpful in a business-to-business setting for professional development and feedback opportunities. The Kodak Grow Your Biz blog is a place for members to learn and share insights about how Kodak products, services, and technologies can improve important company or industry business performance.66 The Pitney Bowes User Forum is a place for members to discuss issues related to Pitney Bowes equipment and to mailing and marketing in general. Members often answer each other’s business questions, though Pitney Bowes customer service representatives are available for any particularly difficult support questions.67

MAXIMIZING THE BENEFITS OF BRAND COMMUNITIES A strong brand community results in a more loyal, committed customer base. One study showed that a multichannel retailer of books, CDs, and DVDs enjoyed long-term incremental revenue of 19 percent from customers—what the authors called “social dollars”— after customers joined an online brand community. The more “connected” a member of the community was, the greater the likelihood he or she would spend more.68

A brand community can be a constant source of inspiration and feedback for product improvements or innovations. The activities and advocacy of members of a brand community can also substitute to some degree for activities the firm would otherwise have to engage in, creating greater marketing effectiveness and efficiency as a result.69

To better understand how brand communities work, one comprehensive study examined communities around brands as diverse as StriVectin cosmeceutical, BMW Mini auto, Jones soda, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers rock and roll band, and Garmin GPS devices. Using multiple research methods such as “netnographic” research with online forums, participant and naturalistic observation of community activities, and in-depth interviews with community members, the researchers found 12 value creation practices taking place. They divided them into four categories—social networking, community engagement, impression management, and brand use—summarized in Table 5.5.

Building a positive, productive brand community requires careful thought and implementation.70 One set of researchers offers these recommendations for making online brand communities more effective:71

- Enhance the timeliness of information exchanged. Set appointed times for topic discussion; give rewards for timely, helpful responses; increase access points to the community.

- Enhance the relevance of information posted. Keep the focus on topic; divide the forum into categories; encourage users to preselect interests.

- Extend the conversation. Make it easier for users to express themselves; don’t set limits on length of responses; allow user evaluation of the relevance of posts.

- Increase the frequency of information exchanged. Launch contests; use familiar social networking tools; create special opportunities for visitors; acknowledge helpful members.

7. WIN-BACKS

Regardless of how hard companies may try, some customers inevitably become inactive or drop out. The challenge is to reactivate them through win-back strategies.72 It’s often easier to reattract ex-customers (because the company knows their names and histories) than to find new ones. Exit interviews and lost- customer surveys can uncover sources of dissatisfaction and help win back only those with strong profit potential.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

There is obviously a bunch to realize about this. I suppose you made certain nice points in features also.