We now look at the operations blueprint: store format, size, and space allocation; personnel utilization; store maintenance, energy management, and renovations; inventory management; store security; insurance; credit management; computerization; outsourcing; and crisis management.

1. Operations Blueprint

An operations blueprint systematically lists all operating functions to be performed, their characteristics, and their timing. When developing a blueprint, the retailer specifies, in detail, every operating function from the store’s opening to closing—and those responsible for them.3 For example, who opens the store? When? What are the steps (turning off the alarm, turning on power, setting up the computer, etc.)? The performance of these tasks must not be left to chance.

A large or diversified retailer may use multiple blueprints and have separate blueprints for such areas as store maintenance, inventory management, credit management, and store displays. When a retailer modifies its store format or operating procedures (such as relying more on selfservice), it must also adjust the operations blueprint(s).

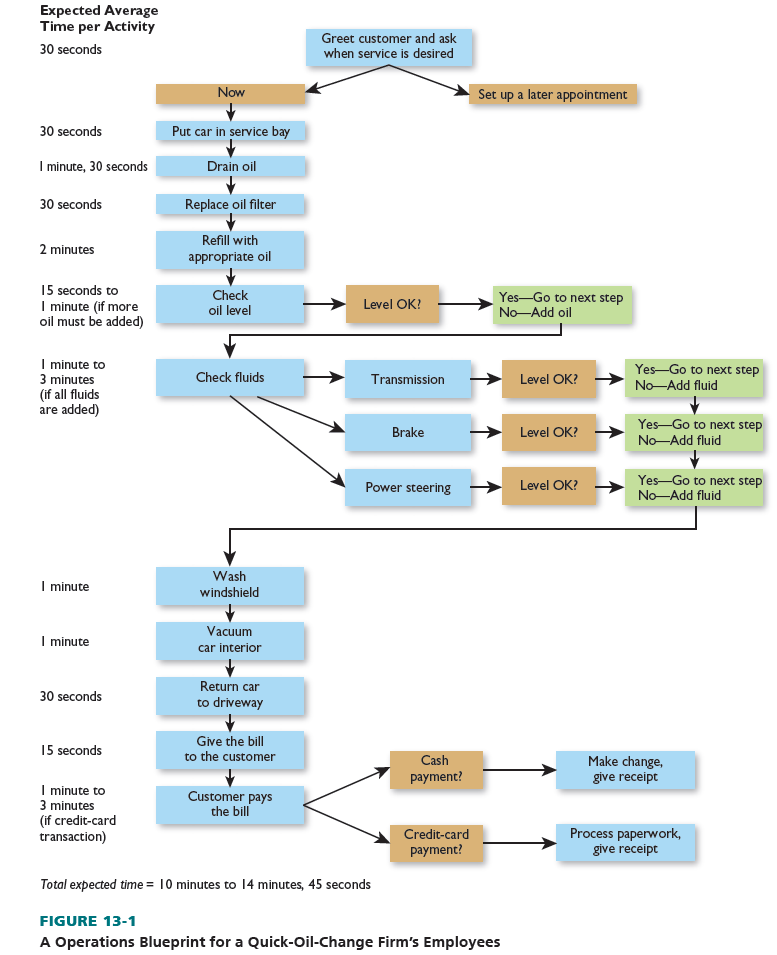

Figure 13-1 has an operations blueprint for a quick-oil-change firm. It identifies employee and customer tasks (in order) and expected performance times for each activity. Advantages of this blueprint—and others—are that it standardizes activities (in a location and between locations), isolates points at which operations may be weak or prone to fail (Do employees actually check transmission, brake, and power-steering fluids in one minute?), outlines a plan that can be evaluated for completeness (Should customers be offered different grades of oil?), shows personnel needs (Should one person change oil and another wash the windshield?), and helps identify productivity improvements (Should the customer or an employee drive a car into and out of the service bay?).

2. Store Format, Size, and Space Allocation

Store format decisions include site planning (such as a planned shopping center rather than an unplanned business district), construction choices (such as prefabricated materials), store size, store design, and store layouts. Some leading retailers use differentiated formats to align assortments to specific consumers and segments, to optimize space profitability, and to create a better customer destination. Multiformat apparel and accessories retailer Inditex has Massimo Dutti stores (personalized service for affluent men and women); Bershka (targeting a younger market with a store resembling a social meeting place); and its core brand Zara (targeting the mid-market, age group 20 to 35 with “cheap and chic” offerings). Some firms, including Target and Walmart (such as Walmart to Go) are using smaller format stores with lower operating costs (for rent, inventory, and lighting) and better access to locations in urban areas—in addition to their larger facilities.

A key store format decision for chain retailers is whether to use prototype stores, whereby multiple outlets conform to relatively uniform construction, layout, and operations standards. They make centralized management control easier, reduce construction costs, standardize operations, facilitate the interchange of employees among outlets, allow bulk purchases of fixtures and other materials, and convey a consistent chain image. Yet, a strict reliance on prototypes may lead to inflexibility, failure to adapt to or capitalize on local customer needs, and too little creativity. McDonald’s, Pep Boys, Starbucks, and most supermarket chains have prototype stores.

Together with prototype stores, some chains use rationalized retailing programs to combine a high degree of centralized management control with strict operating procedures for every phase of business at all of their outlets. Rigid control and standardization make this technique easy to enact and manage, and a firm can add a significant number of stores in a short time. See Figure 13-2. Dunkin’ Donuts, Old Navy, Toys “R” Us, and many major supermarket chains use rationalized retailing. They operate many stores that are similar in size, layout, and merchandising. Rationalized retailing also enables consumers to locate merchandise and to feel comfortable when visiting a new store.

Many retailers use one or both of two contrasting store-size approaches to be distinctive and to deal with high rents in some metropolitan markets. Home Depot, Barnes & Noble, Staples, Best Buy, and Dick’s Sporting Goods have category-killer stores with huge assortments that try to dominate smaller stores. Food-based warehouse stores and large discount-oriented stores often situate in secondary sites, where rents are low and confidence is high that they can draw customers. Cub Foods (a warehouse chain) and Walmart engage in this approach. At the same time, some retailers believe large stores are not efficient in serving saturated (or small) markets; they have been opening smaller stores or downsizing existing ones because of high rents.

Getting the right store and shelf-space management strategy is key to driving traffic, retail sales revenues, and profitability. Retailers have to understand consumer needs, preferences, and purchase behavior across online and offline channels to better “curate” assortments and to optimize their space and assortments. They can use facilities productively by identifying the right amount of space, the right number of brands, and the placement of each product category to most profitably meet retailer and customer needs. Sometimes, retailers drop merchandise lines because they occupy too much space relative to sales, margins, and/or turnover. Today, many department stores focus more on apparel and cosmetics and less on electronics, appliances, and home furnishings (such as carpeting and window treatments).

The growth in cross-channel shopping allows retailers to leverage their Web sites as an “endless aisle” opportunity to extend their offerings without expanding physical space while lowering operating costs. This can support sales of long-tail SKUs (odd sizes, last season’s colors, and so on) at full price, without sacrificing shelf space in stores. To ensure cross-channel coordination, Gap has been testing an “order-in-store” option in several locations, where store customers can place online orders from within the shops with free shipping—if the customer picks up from the store at a later date. This presents opportunities for additional purchases and cross-selling. At Bonobos stores, a men’s clothing retailer, customers can purchase items, but they do not leave with merchandise in-hand; rather, it is shipped to them days later.

With a top-down space management approach, a retailer starts with its total available store space (by outlet and the overall firm, if a chain), divides space into categories, and then works on product layouts. In contrast, a bottom-up space management approach begins planning at the individual product level and then proceeds to category, total store, and overall company levels.

Measures by some retailers to improve store space productivity include vertical displays, which occupy less room and hang on walls and/or from ceilings. Formerly free space may have small point-of-sale displays and vending machines; sometimes, product displays are in front of stores. Open doorways, mirrored walls, and vaulted ceilings give small stores a larger appearance. Up to 75 percent or more of total space may be used for selling; the rest is for storage, rest rooms, and so on. Scrambled merchandising (with high-profit, high-turnover items) occupies more space in stores and at Web sites than before. By having longer hours, retailers can also use space better.

3. Personnel Utilization

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, millions of people work in retailing as salespersons, clerks, customer service representatives, cashiers, and other positions. From an operations perspective, efficiently utilizing retail personnel is vital:

- Labor costs are high—the largest category of controllable, nonmerchandise costs for most retailers, with wages and benefits accounting for up to one-half of operating costs. Forthcoming state and city legislation to raise minimum wages will further lift labor costs.

- High employee turnover means increased recruitment, training, and management costs.

- Poor-performing personnel may have poor sales skills, mistreat shoppers, mis-ring transactions, and make other errors.

- Productivity gains in technology have exceeded those in labor; yet some retailers are still labor intensive.

- Labor scheduling is often subject to unanticipated demand. Retailers know they must increase staff in peak periods and reduce it in slow ones, but they may still be over- or understaffed if weather changes, competitors run specials, or suppliers increase promotions.

- There is less flexibility for firms with unionized employees. Working conditions, compensation, tasks, overtime pay, performance measures, termination procedures, seniority rights, and promotion criteria are generally specified in union contracts.

Because online and mobile shopping account for a larger portion of sales revenues, the role of in-store sales personnel has evolved in response to shoppers’ in-store expectations. Retailers are increasingly equipping in-store personnel with tablets and smartphones, as well as giving them access to customer accounts so they can update data on preferences and anticipated future purchases to enhance cross-selling efforts. Instead of resisting showrooming in their stores, some sales staff help customers find products, check product reviews, and compare prices using the retailers’ mobile apps; order stockouts or irregular-sized products via the retailers’ internal Web sites; and process payment using mobile POS on their tablets. All of this is may be done instead of shoppers lining up at the cashier. Increasingly, customer service personnel are expected to engage with, respond to, and solve customer concerns expressed on blogs, social media, and customer review Web sites.

Tactics to maximize personnel productivity include the following:

- Hiring process. By very carefully screening potential employees before they are offered jobs, turnover is reduced and better performance secured.

- Workload forecasts. For each time period, the number and type of employees are predetermined. A drugstore may have one pharmacist, one cashier, and one stockperson from 2:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M. on weekdays and add a pharmacist and a cashier from 5:00 P.M. to 7:30 P.M. (to accommodate those shopping after work). In workload forecasts, costs must be balanced against the possibilities of lost sales if customer waiting time is excessive. The key is to be both efficient (cost-oriented) and effective (service-oriented). Many retailers use software in employee scheduling. Firms such as Invision (www.invisionwfm.com) have devised software to aid retailers in workload forecasting.

- Job standardization and cross-training. Through job standardization, the tasks of personnel with similar positions in different departments, such as cashiers in clothing and candy departments, are rather uniform. With cross-training, personnel learn tasks associated with more than one job, such as cashier, stockperson, and gift wrapper. A firm increases personnel flexibility, reduces employee boredom and the number of employees needed at any time by job standardization and cross-training. If one department is slow, a cashier could be assigned to a busy one; and a salesperson could process transactions, set up displays, and handle complaints. As consumers increasingly turn to mobile devices, in-store employees need to be trained to use mobile technology to enhance consumer experiences and improve purchase conversion and basket size.

- Good communications. Employees work best when they are clear about their responsibilities and well informed about policies and current company news. See Figure 13-3.

- Employee performance standards. Each worker is given clear goals and is accountable for them. Cashiers are judged on transaction speed and mis-rings, buyers on department revenues and markdowns, and senior executives on the firm’s reaching sales and profit targets. Personnel are more productive when working toward specific goals.

- Compensation. Financial remuneration, promotions, and recognition that reward good performance will help motivate employees. A salesperson is motivated to “cross-sell” goods (ties and shirts with the purchase of a suit) if there is a bonus for related-item selling. Retailers using commission-based or two-tier compensation policies (low base pay plus commission on sales) may need to update their compensation policies to credit employees who persuade in-store shoppers to purchase from the retailer’s Web site as more consumers engage in crosschannel shopping and in-store showrooming. For example, salespeople at Home Depot stores have an incentive to help customers learn how to use the Home Depot mobile app—a mobile- enabled sale anywhere within the ZIP code of their Home Depot store is credited to that store. Self-service. Self-service reduces personnel costs; however, there is less opportunity for crossselling (whereby customers are encouraged to buy complementary goods they may not have been thinking about) and some shoppers may feel service is inadequate. Self-service requires investments in better displays, popular brands, ample assortments, and products with clear labels describing their specifications and features.

- Length of employment. Generally, full-time workers who have been with a firm for an extended time are more productive than those who are part-time or who have worked there for a short time. They are often more knowledgeable, are more anxious to see the firm succeed, need less supervision, are popular with customers, can be promoted, and adapt to the work environment. The superior productivity of these workers normally far outweighs their higher compensation.

4. Store Maintenance, Energy Management, and Renovations

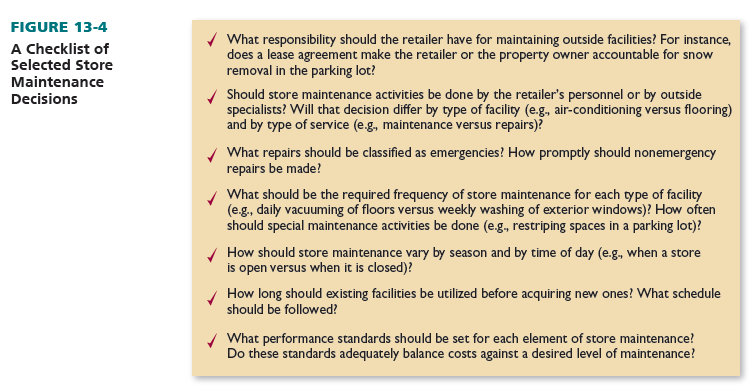

Store maintenance encompasses all activities in managing physical facilities, including exterior (parking lot, points of entry and exit, outside signs and display windows, and common areas adjacent to a store [e.g., sidewalks] and interior (windows, walls, flooring, climate control and energy use, lighting, displays and signs, fixtures, and ceilings). See Figure 13-4.

The quality of store maintenance affects consumer perceptions, the life span of facilities, and operating costs. Consumers do not like poorly maintained stores. This means promptly replacing burned-out lamps and periodically repainting room surfaces. Thorough, ongoing maintenance may extend current facilities for a longer period before having to invest in new ones. At home centers, the heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning equipment last an average of 15 years; display fixtures an average of 12 years; and interior signs an average of 7 years. Maintenance is costly.4 In a typical year, a home center spends $15,000 on floor maintenance alone.

Retail companies spend almost $20 billion on energy every year; however, they have the potential to save $3 billion of that amount through effective energy management programs. A typical 50,000 square foot retail building in the United States spends around $90,000 each year on energy. On average, a store uses 14.3 kilowatt hours of electricity per year, resulting in a cost of $1.47 per square foot. Cutting energy costs by just 10 percent can result in a 1.2 to 1.6 percent increase in profit margins. The same reduction in an average supermarket would result in a 16 percent increase in net profit margins. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that $1 in energy savings is equivalent to increasing sales by $59.5

Due to rising costs over the last 45-plus years, energy management is a major factor in retail operations. For firms with special needs, such as food stores, it is especially critical. To manage their energy resources more effectively, many retailers use a combination of short-term managerial practices and strategic, long-term decisions.

Shorter-term managerial actions include:

- Turning things off. Every kilowatt saved immediately increases profitability.

- Using temperature control devices.Adjust the interior temperature during nonselling hours.

- Indoor lighting upgrades.Replace fluorescent lights with LEDs or CFLs (which use only 20 to 25 percent of the energy of older fluorescents).

- Parking lots.Use lower wattage lighting in parking lots—but security may be an issue.

- Changing HVAC filters regularly.Old filters overwork equipment and use more energy.

- Using sensor lighting.Only utilize lighting when someone is in the room.

- Using reflective paint on roof. This keeps a building cool.

- Cleaning and maintaining refrigerators.This helps machinery operate more efficiently.

Strategic longer-term decisions include:

- Structurally changing buildings.This involves such as actions as energy-efficient windows and using glass instead of walls for natural light (which will also reduce cooling costs).

- Air conditioning/heating. Replace old systems with new energy-efficient units. Install special air-conditioning systems that control humidity levels in specific store areas, such as freezer locations. to minimize moisture condensation.

- Installing computerized systems to monitor and coordinate temperature and lighting levels. Some chains’ systems even allow designated personnel to adjust the temperature, lighting, heat, and air conditioning in multiple stores from one office.

- Insulating. Through better insulation in constructing and renovating stores, heat and cool air are more efficiently controlled.

- Demand-controlled ventilating.Such a system senses carbon dioxide levels, detects how many people are in the store, and saves energy by adjusting ventilation accordingly.

- Adding a building management system (BMS).This system automatically controls and monitors building service performance and makes changes accordingly.

- Energy auditing.This entails partnering with an energy expert to assess current usage and implement a plan for savings.

- Installing solar panels.This involves an alternative form of energy.

- Purchasing Energy Star-approved appliances.These include energy-efficient refrigerators, air conditioning, vending machines, hot food cabinets, and so on.

This example shows how seriously some retailers take energy management: Lighting is a crucial, if seldom noticed, element in the selling atmosphere for LVMH (the parent company of Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Christian Dior, Donna Karan, Marc Jacobs, Bulgari, Sephora, and many others), which occupies nearly 11 million square feet of retail space. Seventy percent of its energy usage goes into stores, not factories or shipping. Optimal, directional lighting has a powerful visual impact that spotlights the aesthetics of luxury products. LVMH’s lighting needs are so complex that the firm researched the best options for hue and those least likely to damage wines, and then signed agreements with 20 LED lighting suppliers. After measuring the energy used by escalators, air conditioning, lighting, and other uses, LVMH realized that computer and digital display screens were devouring almost as much as what the company was saving with the utilization of LED lightbulbs.6

Besides everyday maintenance and energy management, retailers need decision rules for renovations: How often are renovations necessary? What areas require renovations more frequently than others? How extensive will renovations be at any one time? Will the retailer be open for business as usual during renovations? How much money must be set aside in anticipation of future renovations? Will renovations result in higher revenues, lower operating costs, or both?

5. Inventory Management

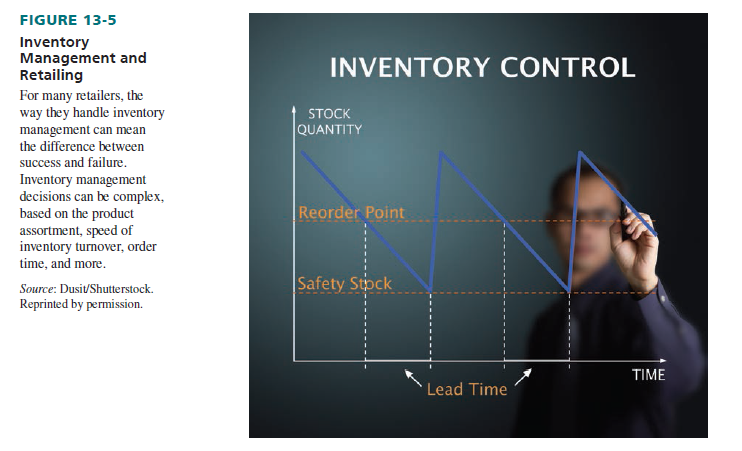

Retailers use inventory management to maintain proper merchandise assortment while ensuring that operations are efficient and effective. See Figure 13-5. Channel boundaries are blurring for shoppers; they are demanding cross-channel service options such as ordering online with in-store pick-up, personalization of products, endless assortments and inventory, and no-cost returns across all channels. Most online-only retailers have optimized the location and number of distribution centers to be able to offer free 3-day delivery; however, many national retailers can leverage their network of stores to offer same-day pick-up if they modernize their inventory and logistics for cross-channel visibility and transfers to prevent stockouts. The item is then likely to be closer to the customer so shipping from stores can be more cost-effective than single-item, direct-to-customer orders from distribution centers accustomed to larger orders bound for stores. Although the role of inventory management in merchandising is covered in Chapter 15, these are some operational issues to consider:

- How can the handling of merchandise from different suppliers be coordinated? In what situations is cross-docking suitable?

- Should drop shipping be employed (wherein manufacturers or wholesalers ship goods directly to consumers based on orders taken at a retail store or Web site)?

- How much inventory should be on the sales floor versus in a warehouse or storeroom?

- How often should inventory be moved from nonselling to selling areas of a store?

- What inventory functions can be done during nonstore hours?

- What are the trade-offs between faster supplier delivery and higher shipping costs?

- What supplier support is expected in storing merchandise or setting up displays?

- What level of in-store merchandise breakage is acceptable?

- Which items require customer delivery? When? By whom?

6. Store Security

Store security relates to two basic issues: personal security and merchandise security. Personal security is examined in this chapter. Merchandise security is covered in Chapter 15. Many shoppers and employees feel less safe at retail shopping locations than before. That is why companies such as ADT offer security support to retailers, including smaller ones (www.adt .com/business).

These are among the practices that retailers are utilizing to address this issue:

- Uniformed security guards provide a visible presence to reassure customers and employees, and they are a warning to potential thieves and muggers. Some shopping areas have horse- mounted guards or guards who patrol on motorized Segway Personal Transporters. As one security expert noted, “Standard practice is for guards to walk the floor to provide a visual reminder that they are there, and report unusual behavior to superiors or to police.”7

- Undercover personnel are used to complement uniformed guards.

- Brighter lighting is used in parking lots, which are also patrolled more frequently by guards. These guards more often work in teams.

- TV cameras and other devices scan areas frequented by shoppers and employees.8 See Figure 13-6. 7-Eleven stores have an in-store cable TVs and alarm monitoring systems, complete with audio.

- Some shopping areas have curfews for teenagers. This is a controversial tactic.

- Access to store backroom facilities (such as storage rooms) is tightened.

- Bank deposits are made more frequently—often by armed security guards.

7. Insurance

Among the types of insurance that retailers buy are workers’ compensation; product liability; fire, accident, property (covering buildings, fixtures. and inventory); liability due to accidents on the premises; business interruption insurance (to cover lost earnings due to fire, floods, etc.); and crime (due to employees stealing cash and goods [inventory shrinkage]). Many firms also offer health insurance to full-time employees, but contributions to premiums differ across retailers. The Affordable Care Act requires employers with 50 or more employees to offer or assist in purchases of health insurance for those working more than 30 hours per week. Some firms still provide insurance coverage to eligible part-time employees, but others—such as Walmart and Target—have discontinued some coverage.

Insurance decisions can have a big impact on a retailer: (1) In recent years, premiums have risen dramatically. (2) Several insurers have reduced the scope of their coverage; they now require higher deductibles or do not provide coverage on all aspects of operations (such as the professional liability of pharmacists). (3) There are fewer insurers servicing retailers today than a decade ago; this limits the choice of carrier. (4) Insurance against environmental risks (such as leaking oil tanks) are more important due to government rules.

To protect themselves financially, retailers have often enacted costly programs aimed at lessening their vulnerability to employee and customer insurance claims from unsafe conditions, as well as to hold down premiums. These programs include no-slip carpeting, flooring, and rubber entrance mats; more frequent inspection of and mopping wet floors; doing more elevator and escalator checks; having regular fire drills; building more fire-resistant facilities; setting up separate storage areas for dangerous items; discussing safety in employee training; and keeping records showing proper maintenance activity.

8. Credit Management

Operational decisions must be made in the area of credit management—for example:

- What form of payment is acceptable? A retailer may accept cash only, cash and personal checks, cash and credit card(s), cash and debit cards, mobile pay, or all of these.

- Who administers the credit plan? The firm can have its own credit system and/or accept major credit cards (such as Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and Discover). It may also work with PayPal, Apple Pay, and Google Checkout for store and online payments. One major innovation in credit management is the availability of free mobile payment apps and portable readers such as Square that plug into an iPod, iTouch, iPhone, or iPad that sales staff or consumers can use to reduce checkout lines at the cashier terminals.9 Another possibility is Touch ID that uses fingerprints in instead of credit cards on selected iPhones and iPads.

- What are customer eligibility requirements for a check or credit purchase? With a check purchase, a photo ID might be sufficient. To open a new credit account, a customer must meet age, employment, income, and other conditions; an existing customer would be evaluated in terms of the outstanding balance and credit limit. Credit reports can be obtained from such firms as Transunion, Equifax, and Experian. These firms consolidate a consumer’s credit risk using a FICO score.

- What credit terms will be used? A retailer with its own plan must determine when interest charges begin to accrue, the rate of interest, and minimum monthly payments.

- How are late payments or nonpayments to be handled? Some retailers with their own credit plans rely on outside collection agencies to follow up on past-due accounts.

The retailer must weigh the ability of credit to increase revenues against the costs of processing payments—screening, transaction, and collection costs, as well as bad debts. If a retailer completes credit functions itself, it incurs these costs; if outside parties (such as Visa) are used, the retailer covers the costs by its fees to the credit organization.

In the United States, there are 185 million credit-card holders. Total retail use of credit and debit cards exceeds $2 trillion. According to U.S. data from CardWeb.com, the average person has three bank-issued cards, four retail credit cards, and one debit card. Based on a survey by the American Bankers Association and Dove Consulting, payments by credit or debit card now account for 53 percent of purchases, versus 43 percent in 1999.

Credit-card fees paid by retailers typically range from 1.5 percent to 5.0 percent of sales for Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express, depending on volume and card provider.10 There may also be transaction and monthly fees. With retailers’ own credit operations, they incur all the processing costs; but they also get to collect the interest on unpaid balances. Walmart and Sears seek to lower transaction fees by promoting consumer use of debit cards, which are less costly for retailers. Debit-card transactions now account for 29 percent of retail card activity versus 17 percent in 1999 according to the Nilson Report.11

Merchants need to monitor consumer preference for various payment methods—cash, debit, credit, check, mobile, and so forth—across generation and income levels. A Federal Reserve study from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice found that the largest share of consumer transaction activity is payment by cash (40 percent), debit-card transactions (29 percent), and credit-card transactions at 17 percent.12 Paper checks have become an antiquated form of payment. Younger consumers and seniors prefer cash or debit cards.

As just noted, many retailers—of all types—now place great emphasis on a debit-card system, whereby the purchase price is immediately deducted from a consumer’s bank account and entered into a retailer’s account by a computer terminal. The retailer’s risk of nonpayment is eliminated, and costs are reduced with debit rather than credit transactions. The pre-paid gift card, a form of debit card, is also popular. For traditional credit cards, monthly billing is employed; with debit cards, monetary account transfers are made at the time of purchase. There is some resistance to debit transactions by those who like the delayed-payment benefit of conventional credit cards. As the payment landscape evolves, new operational issues must be addressed:

- Retailers have more payment options. Online retailers offer many payment choices.13 At store- based retailers, training cashiers is more complex due to all the payment formats, such as cash, third-party and retailer credit and debit cards, personal checks, gift cards, and more. Mobile payment systems introduce more complexity into the process.

- Visa and MasterCard have settled a lawsuit requiring retailers to accept both credit and debit cards, and charging higher interchange fees from retailers for debit cards.

- Nonstore retailers have less legal protection against credit-card fraud than store retailers that secure written authorization. By law, U.S. store retailers were required to update their POS terminals to accept chip-based credit and debit cards by October 1, 2015, or risk assuming liability for counterfeit cards and lost-and-stolen point-of-sale data.14

- Credit-card transactions on the Web must instantly take into account different sales tax rates and currencies (for global sales).

9. Technology and Computerization

CUSTOMER-FACING TECHNOLOGIES Large and small retailers can use a computerized checkout to efficiently process transactions and monitor inventory. These UPC-based scanning systems and computerized registers instantly record and display sales, provide detailed receipts, and retain inventory data. They lower costs by shortening transaction time, employee training, mis- rings, and the need for item pricing. Retailers also have better inventory control, reduced spoilage, and improved ordering. They get item-by-item data, which aid in determining store layout and merchandise plans, shelf space, and inventory replenishment.

Recent technological developments include wireless scanners that let workers scan heavy items without lifting them, radio frequency identification tags (RFID) that emit a radio frequency code when placed near a receiver (which is faster than UPC codes and better for harsh climates), speech recognition (that can tally an order on the basis of a clerk’s verbal command), and portable card readers. See Figure 13-7.

Retailers face two potential problems with computerized checkouts. First, UPC-based systems do not reach peak efficiency unless all suppliers attach UPC labels to merchandise; otherwise, retailers incur labeling costs. Second, because UPC symbols are unreadable by humans, some states have laws that require price labeling on individual items. This lessens the labor savings of posting only shelf prices.

Many retailers have upgraded to an electronic point-of-sale system, which performs all the tasks of a computerized checkout and verifies check and charge transactions, provides instantaneous sales reports, monitors and changes prices, sends intra- and inter-store messages, evaluates personnel and profitability, and stores data. A point-of-sale system is often used along with a retail information system. Point-of-sale terminals can stand alone or be integrated with an in-store or a headquarters computer. As noted in Chapter 2, another scanning option with retailer interest is self-scanning, whereby the consumer himself or herself scans items being purchased at a checkout counter , uses a portable retailer-provided barcode scanner (e.g., for gift registry), or uses the retailer’s mobile app

on a smartphone, and then pays by credit or debit card, and bags items. A potential problem with self-scanning involves the possibility for consumer theft by their leaving more expensive items in the shopping cart and scanning lower-priced items, or scanning items with the barcode covered by one’s hand. Store personnel need to be alert to these and other consumer actions.15

Retailers are increasingly using telecommunications to aid operations via low-cost, secure, in-store transmissions. Retailers use beacon-based technology and applications to push targeted geo-tagged and time-sensitive notifications and promotions to mobile phones of customers in malls to encourage store visits and purchases. Many stores offer free Wi-Fi so customers may scan a barcode for checkout or to check inventory at a nearby location or retailer Web site when the item they are looking for is not in stock. Target’s Cartwheel app allows customers to locate and page the nearest sales associate for help.

SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT TECHNOLOGIES Depending on a retailer’s market size and geography, omnichannel fulfillment can a daunting operation, particularly when customers (not the retailer) decide where and how they would like to receive their purchases among the options offered by the retailer. See Figure 13-8. Sometimes, a linear, pallet-based supply chain (customarily used for large orders bound for stores) can no longer be restricted to a distribution center. Sales associates and store cashiers need authority to send single-line, multiple-category, direct-to- consumer orders from demand-driven supply chains that provide store-shelf collaboration with store backrooms, distribution centers, and a supplier network. When using Amazon’s DRS technology, customers can click Dash tags to order from various manufacturers and specialty retail partners with a simple button.16

Leading store-centric omnichannel retailers such as Lowes recognize the importance of demand-driven supply chains that increase product availability and inventory turnover while reducing cash-to-cash cycle times and costs to serve.17 The focus is on meeting individual consumer demand across channels and on collaborating with suppliers to meet that demand cost effectively.

Cloud (or SaaS) inventory control and order-tracking services that enhance visibility in supply chains are making real-time product fulfillment possible for small and mid-sized retailers. For example, ADC’s InterScale Scales Manager is a fully integrated software application that manages produce and fresh foods in supermarkets and convenience stores. The application identifies the true cost of goods sold and provides hourly forecasts and production plans in real time, thus reducing waste. It can accurately forecast demand for bakery and deli items, hot foods, seafood, produce, dairy, meat, frozen food, floral items, and more.18

Retailers such as Home Depot, Walmart, and J. C. Penney use videoconferencing. This lets them link store employees with central headquarters, as well as interact with vendors. Videoconferencing can be done via satellite technology and by computer (with special hardware and software). Audio/video communications can be used to train workers, spread news, stimulate worker morale, and so on. Polycom, with its SpectraLink product line, is one of the firms marketing lightweight phones so workers can talk to each other anywhere in a store. Polycom clients have included Barnes & Noble, Giant Food, Ikea, Kmart, Neiman Marcus, Rite Aid, and Toys “R” Us.

10. Outsourcing

More retailers have turned to outsourcing for some of the operating tasks they previously performed themselves. With outsourcing, a retailer pays an outside party to undertake one or more of its operating functions. The goals are to reduce the costs and employee time devoted to particular tasks. For example, Limited Brands uses outside firms to oversee its energy use and facilities maintenance. Crate & Barrel outsources the management of its E-mail programs. Apple Stores, Payless Shoes, and Sports Chalet outsource their information technology services. Kmart uses logistics firms to consolidate small shipments and to process returned merchandise; it also outsources electronic data interchange tasks. Home Depot outsources most trucking operations. Retailers also outsource Web design, product delivery, processing of foreign currency transactions, and completion of tariff paperwork to specialized service providers.

Outsourcing delivers operational competences and the ability to quickly respond to customer needs. To combat low margins and commoditization, high-performance retailers leverage outsourcing to increase operational effectiveness and lower costs. Outsourcing can range from IT infrastructure to business process applications. Many firms see outsourcing as a phased process, beginning with infrastructure and ending with business processes managed by a third party. The outsourcer can bring industrywide experience, along with specialist knowledge. Economies of scale drive down unit costs, as do shared resources. Unpredictable capital costs are replaced with variable operational costs.19

11. Crisis Management

Despite the best intentions, retailers may sometimes be faced with crisis situations that need to be managed as smoothly as feasible. Consumer responses to crises depend on the “locus of control”—whether they perceive the causes to be within or outside of the retailer’s control.

Examples of crises brought on by factors outside a retailer’s control include a storm that knocks out store power, unexpectedly high or low consumer demand for a good or service, a burglary, a sudden illness of the owner or a key employee, a sudden increase in a supplier’s prices, or a natural disaster such as a flood or an earthquake. These can be addressed by good marketing communications. However, crises perceived to be within a retailer’s control—such as an in-store fire or broken water pipe (poor maintenance), access to a store being partially blocked due to picketing by striking workers (poor employee relations), a car accident in the retailer’s parking lot, or an in-store data breach compromising customer credit data—can lead to legal and financial penalties, undermine consumer trust, and damage a retailer’s image.

Although many crises can be anticipated, and some adverse effects may occur regardless of retailer efforts, these principles are important:

- There should be contingency plans for as many different types of crisis situations as possible. That is why retailers buy insurance, install backup generators, and prepare management succession plans. A firm can have a checklist to follow if there is an incident such as a store fire or a parking-lot accident.

- A clear chain of command for decision making and external communications must be established and updated.

- Essential information should be communicated to all affected parties, such as the fire or police department, employees, customers, and the media, as soon as a crisis occurs.

- Cooperation—not conflict—among the involved parties is essential.

- Responses should be as swift as feasible; indecisiveness may worsen the situation.

- The firm needs to assess the need for appropriate insurance.

Crisis management is a key task for both small and large retailers. Hence, a thorough contingency plan for responding to a multitude of potential events can mitigate the reputational and financial risks of a crisis.20

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

You are my inhalation, I have few web logs and infrequently run out from to post .