Situation analysis is a candid evaluation of the opportunities and threats facing a prospective or existing retailer. It seeks to answer two general questions: What is the firm’s current status? In which direction should it be heading? Situation analysis means being guided by an organizational mission, evaluating ownership and management options, and outlining the goods/service category to be sold.

A good strategy anticipates and adapts to both the opportunities and threats in a changing business environment. Opportunities are marketplace openings that exist because other retailers have not yet capitalized on them. Ikea does well because it is the pioneer firm in offering a huge selection of furniture at discount prices. Threats are environmental and marketplace factors that can adversely affect retailers if they do not react to them (and, sometimes, even if they do). Single-screen movie theaters have virtually disappeared because they have been unable to fend off multiscreen theaters. Movies available via pay-per-view services and streaming movies by subscription services like Netflix and Amazon are additional threats to the movie theater industry.

A firm needs to spot trends early enough to satisfy customers and stay ahead of competitors, yet not so early that shoppers are not ready for changes or that false trends are perceived. Merchandising shifts—such as stocking fad items—are more quickly enacted than changes in a firm’s location, price, or promotion strategy. A new retailer can adapt to trends easier than existing ones with established images, ongoing leases, and space limitations. Well-prepared small firms can compete with large retailers due to their nimbleness.

In situation analysis, especially for a new retailer or one thinking about a major strategic change, an honest, in-depth self-assessment is vital. It is all right for a person or company to be ambitious and aggressive, but overestimating one’s abilities and prospects may be harmful—if it results in entry into the wrong retail business, inadequate resources, or misjudging competitors.

1. Organizational Mission

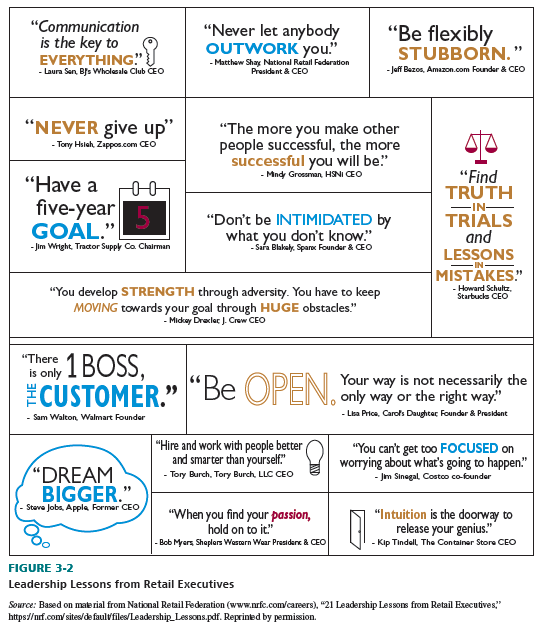

An organizational mission is a retailer’s commitment to a type of business and to a distinctive role in the marketplace. It is reflected in the firm’s attitude toward consumers, employees, suppliers, competitors, government, and others. A clear mission lets a firm gain a customer following and distinguish itself from competitors. Figure 3-2 highlights some inspirational quotes from prominent executives that retailers should keep in mind when devising their missions.

One major decision is whether to base a business around the goods and services sold or around consumer needs. A person opening a hardware business must decide if, in addition to hardware products, a line of bathroom vanities should be stocked. A traditionalist might not carry vanities because they seem unconnected to the proposed business. But if the store is to be a do-it- yourself home improvement center, vanities are a logical part of the mix. That store would carry any relevant items the consumer wants.

A second major decision is whether a retailer wants a place in the market as a leader or a follower. It could seek to offer a unique strategy, such as Taco Bell becoming the first national quick-serve Mexican food chain. Or it could emulate practices of competitors but do a better job executing them, such as a local fast-food Mexican restaurant offering five-minute guaranteed service and a cleanliness pledge.

A third decision involves market scope. Large chains often seek a broad customer base (due to their resources and recognition). It is often best for small retailers and startups to focus on a narrower customer base, so they can compete in a local versus a regional marketplace.

Although the development of an organizational mission is the first step in the planning process, a firm’s mission should be continually reviewed and adjusted to reflect changing company goals and a dynamic retail environment. Here is an example of how Amazon’s organizational mission has evolved since it launched online in July 1995.

Its initial mission was to use the Internet to transform book buying into the fastest, easiest, and most enjoyable shopping experience possible.3 Since then, Amazon has grown in sales revenues ($100 billion in 2015)4 and in product offerings to be the seventh largest retailer in the world. As a result, its mission statement has become much broader, but the focus and commitment to customer satisfaction and the delivery of an educational shopping experience has remained.5

2. Ownership and Management Alternatives

An essential aspect of situation analysis is assessing ownership and management alternatives, including whether to form a sole proprietorship, partnership, or corporation—and whether to start a new business, buy an existing business, or become a franchisee.6 Management options include owner-manager versus professional manager and centralized versus decentralized structures. There is no one best ownership type for a retailer; the type of legal structure impacts taxation, personal liability, record keeping, and the ability to raise money. The limitations of a particular form of ownership can often be overcome. For instance, a sole proprietor can buy insurance coverage to reduce liability exposure. Astute entrepreneurs re-evaluate their choice of entity as their business evolves. The Small Business Association (SBA) and an experienced attorney or tax advisor are valuable sources of information and advice for a business.7

A sole proprietorship is an unincorporated retail firm owned by one person. All benefits, profits, risks, and costs accrue to that individual. It is simple to form, fully controlled by the owner, operationally flexible, easy to dissolve, and subject to single taxation by the government. It makes the owner personally liable for legal claims from suppliers, creditors, and others; it can also lead to limited capital and expertise.

A partnership is an unincorporated retail firm owned by two or more persons, each with a financial interest. Partners share benefits, profits, risks, and costs. Advantages include the following: Responsibility and expertise are divided among multiple principals, there is a greater capability for raising funds than with a proprietorship, the format is simpler to form than a corporation, and it is subject to single taxation by the government. Depending on the type of partnership, it can make owners personally liable for legal claims, can be dissolved due to a partner’s death or a disagreement, it binds all partners to actions made by any individual partner acting on behalf of the firm, and it usually has less ability to raise capital than a corporation.

A corporation is a retail firm that is formally incorporated under state law. It is a legal entity apart from individual officers (or stockholders). Funds can be raised through the sale of stock; legal claims against individuals are not usually allowed; ownership transfer is relatively easy; the firm is more assured of long-term existence (if a founder leaves, retires, or dies); the use of professional managers is encouraged; and unambiguous operating authority is outlined. Depending on the type of corporation, it is subject to double taxation (company earnings and stockholder dividends), faces more government rules, can require a complex process when established, may be viewed as impersonal, and may separate ownership from management. A closed corporation is run by a limited number of persons who control ownership; stock is not available to the public. In an open corporation, stock is traded and available to the public.

Sole proprietorships account for 74 percent of U.S. retail firms filing tax returns, partnerships for 6 percent, and corporations for 20 percent. Yet, sole proprietorships account for just 5 percent of total U.S. retail store sales, partnerships for 10 percent, and corporations for 85 percent.8

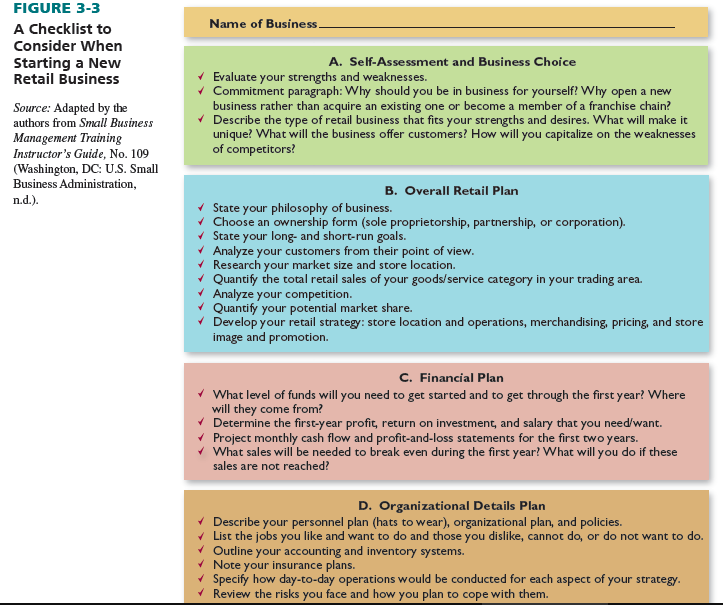

Starting a new business—being entrepreneurial—offers a retailer flexibility in location, operating style, product lines, customer markets, and other factors, and involves planning and implementing a strategy that is fully tailored to the owner’s desires and strengths. There may be high construction costs, a time lag until the business is opened and then until profits are earned, beginning with an unknown name, and having to form supplier relationships and amass an inventory of goods. Figure 3-3 presents a checklist to consider when starting a retail business.

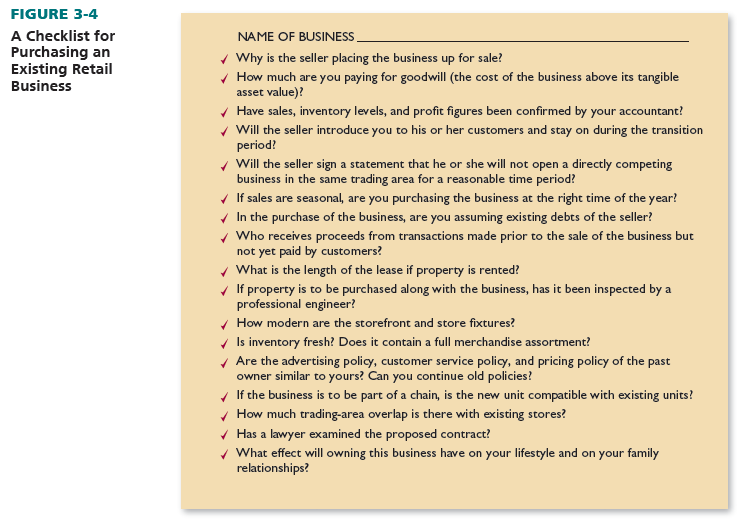

Buying an existing business allows a retailer to acquire an established company name, a customer following, a good location, trained personnel, and facilities; to operate immediately; to generate ongoing sales and profits; and to possibly get good lease terms or financing (at low interest rates) from the seller. A few disadvantages are that fixtures may be older, there is less flexibility in enacting a strategy tailored to the new owner’s desires and strengths, and the growth potential of the business may be limited. One issue that must be examined in purchasing is the valuation of a firm’s existing inventory. Figure 3-4 shows a checklist to consider when purchasing an existing retail business.

By being a franchisee, a retailer can combine independent ownership with franchisor support such as strategic planning assistance; a known company name and loyal customer following; cooperative advertising and buying; and a regional, national, or global (rather than local) image. However, a franchisee contract may specify rigid operating standards, limit the product lines sold, and restrict supplier choice; the franchisor company is usually paid continuously (royalties); advertising fees may be required; and there is a possibility of termination by the franchisor if the agreement is not followed satisfactorily.

Strategically, the management format also has a dramatic impact. With an owner-manager, planning tends to be less formal and more intuitive, and many tasks are reserved for that person (such as employee supervision and cash management). With professional management, planning tends to be more formal and systematic. Yet, professional managers are more constrained in their authority than an owner-manager. In a centralized structure, planning clout lies with top management or ownership; managers in individual departments have major input into decisions with a decentralized structure.

A comprehensive discussion of independent retailers, chains, franchises, leased departments, vertical marketing systems, and consumer cooperatives is included in Chapter 4.

3. Goods/Service Category

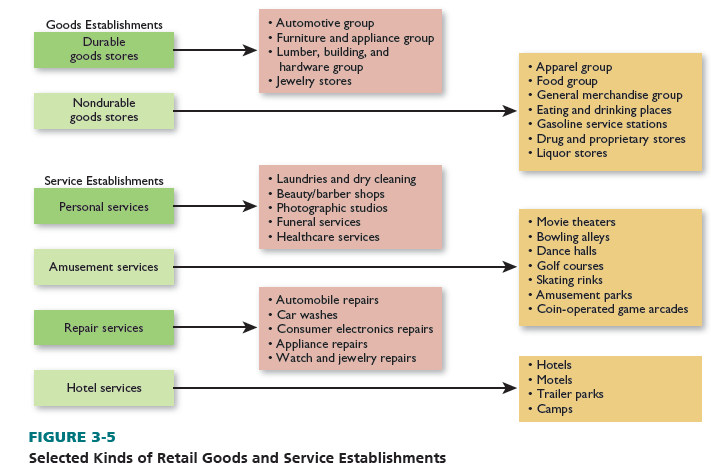

Before a prospective retail firm can fully design a strategic plan, it selects a goods/service category—the line of business—in which to operate. Figure 3-5 shows the diversity of goods/ service categories. Chapter 5 examines the attributes of food-based and general merchandise store retailers. Chapter 6 focuses on Web, nonstore, and other forms of nontraditional retailing.

It is advisable to specify both a general goods/service category and a niche within that category. Mercedes dealers are luxury auto retailers catering to upscale customers. Wendy’s is a chain known for its quality fast food with a menu emphasizing hamburgers. Motel 6 is a chain whose strength is inexpensive, clean, and centrally located hotel rooms with few frills.

A potential retail business owner should select a type of business that will allow him or her to match personal abilities, financial resources, and time availability with the requirements of that kind of business. Visit our blog (www.bermanevansretail.com) for links to many retail trade associations that represent various goods/service categories.

4. Personal Abilities

Personal abilities depend on an individual’s aptitude—the preference for a type of business and the potential to do well; education—formal learning about retail practices and policies; and experience—practical learning about retail practices and policies.

An individual who wants to run a business, shows initiative, and has the ability to react quickly to competitive developments will be suited to a different type of situation than a person who depends on others for advice and does not like to make fast decisions. The first individual could be an independent operator in a dynamic business such as apparel; the second might seek partners or a franchise and a stable business, such as a stationery store. Some people enjoy customer interaction; they would dislike the impersonality of a self-service operation. Others enjoy the impersonality of mail-order or Web retailing.

In certain fields, education and experience requirements are specified by law. Stockbrokers, real-estate brokers, beauticians, pharmacists, and opticians must all satisfy educational or experience standards to show competency. For example, real-estate brokers are licensed after a review of their knowledge of real-estate practices and their ethical character. The legal designation “broker” does not depend on the ability to sell or have a customer-oriented demeanor.

Some skills can be learned; others are inborn. Accordingly, potential retail owners have to assess their skills and match them with the demands of a given business. This involves careful reflection about oneself. Partnerships may be best when two or more parties possess complementary skills. A person with selling experience may join with someone who has the operating skills

to start a business. Each partner has valued skills, but he or she may be unable to operate a retail entity without the expertise of the other.

5. Financial Resources

Many retail enterprises, especially new, independent ones, fail because the owners do not adequately project the financial resources needed to open and operate the firm. Table 3-1 outlines some of the typical investments for a new retail venture.

Novice retailers tend to underestimate the value of a personal drawing account, which is used for the living expenses of the owner and his or her family in the early, unprofitable stage of a business. Because few new ventures are immediately profitable, the budget must include such expenditures. In addition, the costs of renovating an existing facility often are miscalculated. Underfunded firms usually invest in only essential renovations. This practice reduces the initial investment, but it may give the retailer a poor image. Merchandise assortment, as well as the types of goods and services sold, also affects the financial outlay. Finally, the use of a partnership, corporation, or franchise agreement will affect the investment.

Table 3-2 illustrates the financial requirements for a hypothetical used-car dealer. The initial personal savings investment of $300,000 would force many potential owners to rethink the choice of product category and the format of the firm: (1) The plans for a 40-car inventory reflect this owner’s desire for a balanced product line. If the firm concentrates on subcompact, compact, and intermediate cars, it can reduce inventory size and lower the investment, (2) the initial investment can be reduced by seeking a location whose facilities do not have to be modified, and (3) fewer financial resources are needed if a partnership or corporation is set up with other individuals, so that costs—and profits—are shared.

The U.S. Small Business Administration (www.sba.gov) assists businesses by guaranteeing thousands of loans each year. Such private companies as Wells Fargo and American Express also financial support and advice have financing programs specifically aimed at small businesses.

6. Time Demands

Time demands on retail owners (or managers) differ significantly by goods or service category. They are influenced both by consumer shopping patterns and by the ability of the owner or manager to automate operations or delegate activities to others.

Many retailers must have regular weekend and evening hours to serve time-pressed shoppers. Gift shops, toy stores, and others have extreme seasonal shifts in their hours. Mail-order firms and those selling through the Web, which can process orders during any part of the day, have more flexible hours.

Some businesses require less owner involvement, including gas stations with no repair services, coin-operated laundries, and movie theaters. The emphasis on automation, self-service, standardization, and financial controls lets the owner reduce her or his time. Other businesses, such as hair salons, restaurants, and jewelry stores, require more active owner involvement. Intensive owner participation can be the result of several factors:

- The owner may be the key service provider, with patrons attracted by his or her skills (the major competitive advantage). Delegating work to others will lessen consumer loyalty.

- Personal services are not easy to automate.

- Due to limited funds, the owner and his or her family must often undertake all operating functions for a small retail firm. Spouses and/or children work in 40 percent of family-owned businesses.

- In a business that operates on a cash basis, the owner must be around to avoid being cheated.

Off-hours activities are often essential. At a restaurant, some foods must be prepared in advance of the posted dining hours. An owner of a small computer store cleans, stocks shelves, and does the books during the hours the firm is closed. A prospective retail owner also has to examine his or her time preferences regarding stability versus seasonality, ideal working hours, and personal involvement.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Keep up the superb piece of work, I read few blog posts on this website and I believe that your web blog is rattling interesting and has bands of superb information.

I was looking through some of your blog posts on this website and I think this website is rattling informative ! Retain putting up.