Traditionally, marketers played the role of intermediary, charged with understanding customers’ needs and transmitting their voice to various functional areas.5 But in a networked enterprise, every functional area can interact directly with customers. Marketing no longer has sole ownership of customer interactions; it now must integrate all the customer-facing processes so customers see a single face and hear a single voice when they interact with the firm.6

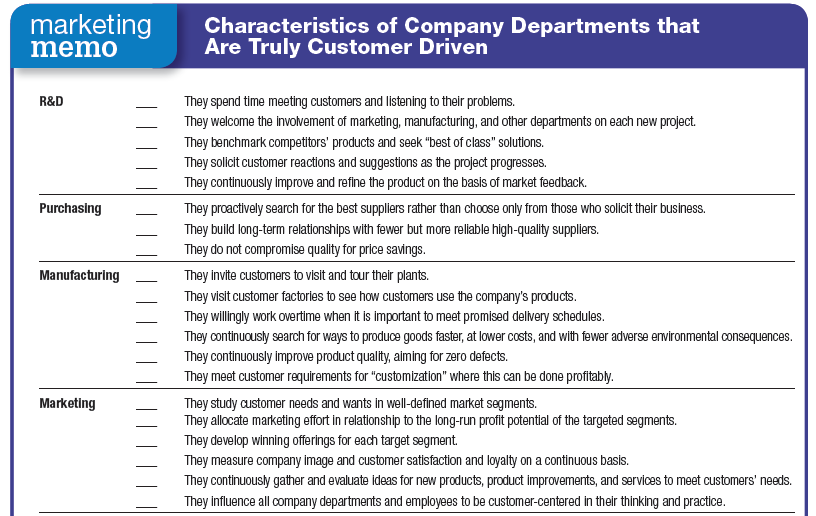

Internal marketing requires that everyone in the organization accept the concepts and goals of marketing and engage in identifying, providing, and communicating customer value. Only when all employees realize their job is to create, serve, and satisfy customers does the company become an effective marketer.7 “Marketing Memo: Characteristics of Company Departments That Are Truly Customer Driven” presents a tool that evaluates which company departments excel at being customer-centric.

Let’s look at how marketing departments are being organized, how they can work effectively with other departments, and how firms can foster a creative marketing culture across the organization.8

1. ORGANIZING THE MARKETING DEPARTMENT

Modern marketing departments can be organized in a number of different, sometimes overlapping ways: functionally, geographically, by product or brand, by market, or in a matrix.

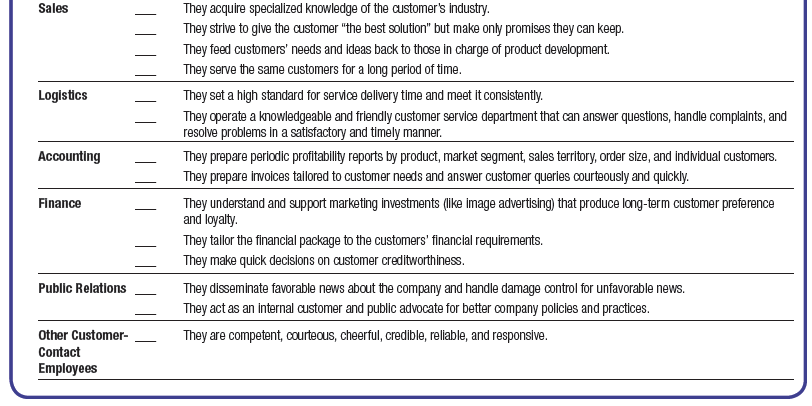

FUNCTIONAL ORGANIZATION In the most common form of marketing organization, functional specialists report to a marketing vice president who coordinates their activities. Figure 23.1 shows five specialists. Others might include a customer service manager, a marketing planning manager, a market logistics manager, a direct marketing manager, and a digital marketing manager.

The main advantage of a functional marketing organization is its administrative simplicity. It can be quite a challenge for the departments to develop smooth working relationships, however. This form also can result in inadequate planning as the number of products and markets increases and each functional group vies for budget and status. The marketing vice president constantly weighs competing claims and faces a difficult coordination problem.

GEOGRAPHIC ORGANiZATION A company selling in a national market often organizes its sales force (and sometimes its marketing) along geographic lines.9 The national sales manager may supervise four regional sales managers, who each supervise six zone managers, who in turn supervise eight district sales managers, who each supervise 10 salespeople.

Some companies are adding area market specialists (regional or local marketing managers) to support sales efforts in high-volume markets. One such market might be Miami-Dade County, Florida, where almost two-thirds of households are Hispanic.10 The Miami specialist would know Miami’s customer and trade makeup, help marketing managers at headquarters adjust their marketing mix for Miami, and prepare local annual and long-range plans for selling all the company’s products there. Some companies must develop different marketing programs in different parts of the country because geography alters their brand development so much, as noted in Chapter 8.

PRODUCT- OR BRAND-MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATION Companies producing a variety of products and brands often establish a product- (or brand-) management organization. This does not replace the functional organization but serves as another layer of management. A group product manager supervises product category managers, who in turn supervise specific product and brand managers.

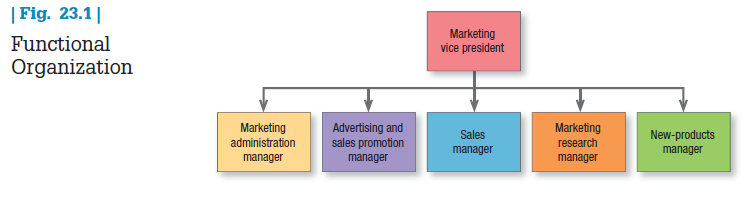

A product-management organization makes sense if the company’s products are quite different or there are more than a functional organization can handle. This form is sometimes characterized as a hub-and-spoke system. The brand or product manager is figuratively at the center, with spokes leading to various departments representing working relationships (see Figure 23.2). The manager may:

- Develop a long-range and competitive strategy for the product.

- Prepare an annual marketing plan and sales forecast.

- Work with advertising, digital, and merchandising agencies to develop copy, programs, and campaigns.

- Increase support of the product among the sales force and distributors.

- Gather continuous intelligence about the product’s performance, customer and dealer attitudes, and new problems and opportunities.

- Initiate product improvements to meet changing market needs.

The product-management organization lets the product manager concentrate on developing a cost-effective marketing program and react more quickly to new products in the marketplace; it also gives the company’s smaller brands a product advocate. However, it has disadvantages too:

- Product and brand managers may lack authority to carry out their responsibilities.

They become experts in their product area but rarely achieve functional expertise. - The system often proves costly. One person is appointed to manage each major product or brand, and soon more are appointed to manage even minor products and brands.

- Brand managers normally manage a brand for only a short time. Short-term involvement leads to short-term planning and fails to build long-term strengths.

- The fragmentation of markets makes it harder to develop a national strategy. Brand managers must please regional and local sales groups, transferring power from marketing to sales.

- Product and brand managers focus the company on building market share rather than customer relationships.

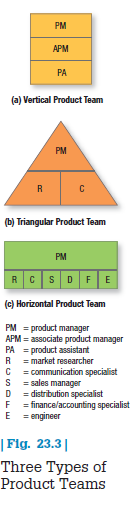

A second alternative in a product-management organization is product teams. There are three types: vertical, triangular, and horizontal (see Figure 23.3). The triangular and horizontal product-team approaches let each major brand be run by a brand-asset management team (BAMT) consisting of key representatives from functions that affect the brand’s performance. The company consists of several BAMTs that periodically report to a BAMT directors committee, which itself reports to a chief branding officer. This is quite different from the way brands have traditionally been handled.

A third alternative is to eliminate product manager positions for minor products and assign two or more products to each remaining manager. This is feasible when two or more products appeal to a similar set of needs. A cosmetics company doesn’t need product managers for each product because cosmetics serve one major need—beauty. A toiletries company needs different managers for headache remedies, toothpaste, soap, and shampoo because these products differ in use and appeal.

In a fourth alternative, category management, a company focuses on product categories to manage its brands. Procter & Gamble (P&G), a pioneer of the brand-management system, and other top packaged-goods firms have made a major shift to category management, as have firms outside the grocery channel.11 Diageo’s shift to category management was seen as a means to better manage the development of premium brands. It also helped the firm address the plight of under-performing brands.12

P&G cited a number of advantages to its shift to category management. By fostering internal competition among brand managers, the traditional brand-management system had created strong incentives to excel, but also internal competition for resources and a lack of coordination. The new scheme was designed to ensure adequate resources for all categories.

Another rationale is the increasing power of the retail trade, which has thought of profitability in terms of product categories. P&G felt it only made sense to deal along similar lines. Retailers and regional grocery chains such as Walmart and Dominick’s embrace category management as a means to define a particular product category’s strategic role within the store and address logistics, the role of private-label products, and the trade-offs between product variety and inefficient duplication.13

In fact, in some packaged-goods firms, category management has evolved into aisle management and encompasses multiple related categories typically found in the same sections of supermarkets and grocery stores. General Mills’ Yoplait Yogurt has served as category advisor to the dairy aisle for 24 major retailers, boosting the yogurt base footprint four to eight feet at a time and increasing sales of yogurt by 9 percent and category sales in dairy by 13 percent nationwide.14

MARKET-MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATION Canon sells printers to consumer, business, and government markets. Nippon Steel sells to the railroad, construction, and public utility industries. When customers fall into different user groups with distinct buying preferences and practices, a market- management organization is desirable. Market managers supervise several market-development managers, market specialists, or industry specialists and draw on functional services as needed. Market managers of important markets might even have functional specialists reporting to them.

Market managers are staff (not line) people, with duties like those of product managers. They develop long-range and annual plans for their markets and are judged by their market’s growth and profitability. Because this system organizes marketing activity to meet the needs of distinct customer groups, it shares many advantages and disadvantages of product-management systems. Many companies are reorganizing along market lines and becoming market- centered organizations. Xerox converted from geographic selling to selling by industry, as did IBM and Hewlett-Packard.

When a close relationship is advantageous, such as when customers have diverse and complex requirements and buy an integrated bundle of products and services, a customer-management organization, which deals with individual customers rather than the mass market or even market segments, should prevail.15 One study showed that companies organized by customer groups reported much higher accountability for the overall quality of relationships and greater employee freedom to take actions to satisfy individual customers.16

MATRIX-MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATION Companies that produce many products for many markets may adopt a matrix organization employing both product and market managers. The rub is that it’s costly and often creates conflicts. There’s the cost of supporting all the managers and questions about where authority and responsibility for marketing activities should reside—at headquarters or in the division?17 Some corporate marketing groups assist top management with overall opportunity evaluation, provide divisions with consulting assistance on request, help divisions that have little or no marketing, and promote the marketing concept throughout the company.

2. RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHER DEPARTMENTS

Under the marketing concept, all departments need to “think customer” and work together to satisfy customer needs and expectations. Yet departments define company problems and goals from their own viewpoints, so conflicts of interest and communications problems are unavoidable. The marketing vice president or the CMO must usually work through persuasion rather than through authority to coordinate the company’s internal marketing activities and coordinate marketing with finance, operations, and other company functions to serve the customer.18

Many companies now focus on key processes rather than on departments because departmental organization can be a barrier to smooth performance. They appoint process leaders, who manage cross-disciplinary teams that include marketing and salespeople. Marketers thus may have a solid-line responsibility to their teams and a dotted- line responsibility to the marketing department.

Given the goal of providing positive customer experiences from start to finish, all areas of the organization need to work effectively together. In particular, because of the growing importance of “Big Data,” marketers must work closely with those in the IT department to gain critical insights and updates.

3. BUILDING A CREATIVE MARKETING ORGANIZATION

Many companies realize they’re not yet really market and customer driven—they are product and sales driven. Transforming into a true market-driven company requires, among other actions: (1) developing a company-wide passion for customers; (2) organizing around customer segments instead of products; and (3) understanding customers through qualitative and quantitative research.

The task is not easy, but the payoffs can be considerable. See “Marketing Insight: The Marketing CEO” for concrete actions a CEO can take to improve marketing capabilities.

Although it’s necessary to be customer oriented, it’s not enough. The organization must also be creative.19 Companies today copy each others’ advantages and strategies with increasing speed, making differentiation harder to achieve and lowering margins as firms become more alike. The only answer is to build a capability in strategic innovation and imagination. This capability comes from assembling tools, processes, skills, and measures that let the firm generate more and better new ideas than its competitors.20 Companies also try to put together inspiring work spaces that help to stimulate new ideas and foster imagination.

Companies must watch trends and be ready to capitalize on them. Nestle was late seeing the trend toward coffeehouses such as Starbucks. Coca-Cola was slow to pick up beverage trends toward fruit-flavored drinks such as Snapple, energy drinks such as Gatorade, and designer water brands. Market leaders can miss trends when they are risk averse, obsessed about protecting their existing markets and physical resources, and more interested in efficiency than innovation.21

4. MARKETING INSIGHT The Marketing CEO

What steps can a CEO take to create a market- and customer-focused company?

- Convince senior management of the need to become customer focused. The CEO personally exemplifies strong customer commitment and rewards those in the organization who do likewise. Former CEOs Jack Welch of GE and Lou Gerstner of IBM famously spent 100 days a year visiting customers in spite of their many strategic, financial, and administrative burdens.

- Appoint a senior marketing officer and marketing task force. The marketing task force should include the CEO; C-level executives from sales, R&D, purchasing, manufacturing, finance, and human resources; and other key individuals.

- Get outside help and guidance. Consulting firms have considerable experience helping companies adopt a marketing orientation.

- Change the company’s reward measurement and system. As long as purchasing and manufacturing are rewarded for keeping costs low, they will resist accepting some costs required to serve customers better. As long as finance focuses on short-term profit, it will oppose major investments designed to build satisfied, loyal customers.

- Hire strong marketing talent. The company needs a strong chief marketing officer who not only manages the marketing department but also gains respect from and influence with the other C-level executives. A multidivisional company will benefit from establishing a strong corporate marketing department.

- Develop strong in-house marketing training programs. The company should design well-crafted marketing training programs for corporate management, divisional general managers, marketing and sales personnel, manufacturing personnel, R&D personnel, and others. Many companies such as GE, Unilever, and Accenture have centralized training facilities to run such programs.

- Install a modern marketing planning system. The planning format will require managers to think about the marketing environment, opportunities, competitive trends, and other forces. These managers then prepare strategies and sales-and-profit forecasts for specific products and segments and are accountable for performance.

- Establish an annual marketing excellence recognition program. Business units that believe they’ve developed exemplary marketing plans should submit a description of their plans and results. Winning teams should be rewarded at a special ceremony and the plans disseminated to the other business units as “models of marketing thinking.” Procter & Gamble, SABMiller, and Becton, Dickinson and Company follow this strategy.

- Shift from a department focus to a process-outcome focus. After defining the fundamental business processes that determine its success, the company should appoint process leaders and cross-disciplinary teams to reengineer and implement these processes.

- Empower the employees. Progressive companies encourage and reward their employees for coming up with new ideas and empower them to settle customer complaints to save the customer’s business. IBM lets frontline employees spend as much as $5,000 to solve a customer problem on the spot.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Great post. I was checking constantly this blog and I’m impressed! Extremely useful information particularly the last part 🙂 I care for such info much. I was seeking this certain info for a long time. Thank you and good luck.