As part of its logistics efforts, a retailer utilizes inventory management to acquire and maintain a proper merchandise assortment while ordering, shipping, handling, storing, displaying, and selling costs are kept in check. First, a retailer places an order based on a sales forecast or actual customer behavior. Both the number of items and their variety are requested when ordering. Order size and frequency depend on quantity discounts and inventory costs. Second, a supplier fills the order and sends the merchandise to a warehouse or directly to the store(s). Third, the retailer receives the products, makes items available for sale (by removing them from packing, marking prices, and placing them on the sales floor), and completes customer transactions. Some transactions are not concluded until the items are delivered to the customer. The cycle starts anew as a retailer places another order. Let’s look at these aspects of inventory management: retailer tasks, inventory levels, merchandise security, reverse logistics, and inventory analysis.

1. Retailer Tasks

Due to the comprehensive nature of inventory management, and to be more cost-effective, some retailers now expect suppliers to perform more tasks or ship floor-ready merchandise, or they outsource at least part of their inventory management activities rather than accept warehouse- ready merchandise as in the 1990s. Today, and in the future, more manufacturers will shift to consumer-ready manufacturing where the links between producer and consumer will be more direct.23 Here are some examples:

- Walmart and other retailers count on key suppliers to participate in their inventory management programs. Industrywide, this practice is known as vendor-managed inventory (VMI). Procter & Gamble even has its own employees stationed at Walmart headquarters to manage the inventory replenishment of that manufacturer’s products.24

- Target Corporation is at the forefront of another trend—store-based retailers doing their own customer order fulfillment for their online, especially mobile, businesses (as those businesses grow) or partnering with on-demand logistics companies such as Instacart to provide a menu of flexible services to customers. Services include regular online delivery, online with 1- to 2-hour delivery, ship from store, curbside pickup, and Target subscriptions for repeat purchasers. Target’s Cartwheel and Curbside mobile apps account for 40 percent of digital orders and go beyond providing promotional discounts to serving in-store customer assistants, creating a personalized in-store experience, or offering an ordering portal that provides drive-thru service.25

- According to the National Association for Retail Merchandising Services (www.narms.com), well over $3 billion annually in retail merchandising services—ranging from reordering to display design—are provided by specialized firms. An example is New Concepts in Marketing, which has provided ordering and inventory control, promotional selling, display placement, and other services for such clients as Babies “R” Us, Kmart, Publix, and Sam’s Clubs.

One contentious inventory management activity involves who is responsible for tagging: the manufacturer or the retailer? In source tagging, antitheft tags are put on items when they are made, rather than at the store. Although both sides agree on the benefits of this, in terms of reduced costs and floor-readiness of merchandise, there are disagreements about who should pay for the tags.

2. Inventory Levels

Having the proper inventory on hand is a difficult balancing act:

- The retailer wants to be appealing and never lose a sale by being out of stock. Yet, it does not want to be “stuck” with excess merchandise that must be marked down drastically.

- The situation is more complicated for retailers that carry fad merchandise, handle new items for which there is no track record, and operate in new business formats where demand estimates are often inaccurate. Thus, inventory levels must be planned in relation to the products involved: staples, assortment merchandise, fashion merchandise, fads, and best-sellers.

- Customer demand is never completely predictable—even for staple items. Weather, special sales, and other factors can have an impact on even the most stable items.

- Shelf space allocations should be linked to current revenues, which means that allocations must be regularly reviewed and adjusted.

One of the advantages of QR and EDI is that retailers hold “leaner” inventories because they receive new merchandise more often. Yet, when merchandise is especially popular or the supply chain breaks down, stockouts may still occur. A Food Marketing Institute study found that even supermarkets, which carry more staples than most other retailers, lose 3 percent of sales due to out-of-stock goods.

Inventory level planning is discussed further in the next chapter.

3. Merchandise Security

Each year, tens of billions of dollars in U.S. retail sales—are lost due to inventory shrinkage caused by employee theft, customer shoplifting, vendor fraud, organized crime, and administrative errors. According to the National Retail Security Survey 2015, shoplifting accounts for 38 percent of overall shrinkage, employee theft 34.5 percent, administrative and paperwork errors 16.5 percent, vendor fraud or error 6.8 percent, and unknown loss 4.2 percent.26

The overall shrinkage for the United States is about 1.4 percent of sales. This means a small store with $500,000 in annual sales might lose up to $7,000 or more due to shrinkage, and a large store with $20 million in sales might lose up to $280,000 or more due to shrinkage. Thus, some form of merchandise security is needed by all retailers. Theft prevention devices include smart tagging (which uses radio frequency identification to track stolen goods), exit sensors (that make loud sounds when a thief exits the store), and source tagging (tags sewn into garments).

To reduce merchandise theft, there are three key points to consider: (1) Loss-prevention measures should be incorporated as stores are designed and built. The placement of entrances, dressing rooms, and delivery areas is critical. (2) A combination of security measures should be enacted, such as employee background checks, in-store guards, electronic security equipment, and merchandise tags. (3) Retailers must communicate the importance of loss prevention to employees, customers, and vendors—and the actions they are prepared to take to reduce losses (such as firing workers and prosecuting shoplifters).

The following activities are reducing losses from merchandise theft:

- Product tags, guards, video cameras, point-of-sale computers, employee surveillance, and burglar alarms are being used by more firms. Storefront protection is also popular. See the left side of Figure 15-11.

- Many general merchandise retailers and some supermarkets use electronic article surveillance—whereby special tags are attached to products so that the tags can be sensed by electronic security devices at store exits. If the tags are not removed by store personnel or desensitized by scanning equipment, an alarm goes off. Retailers also have access to nonelectronic tags. These are snugly attached to products and must be removed by special detachers; otherwise products are unusable. Dye tags permanently stain products, if not removed properly. See the right side of Figure 15-11.

- A number of retailers do detailed background checks for each prospective new employee. Some use loss-prevention software that detects suspicious employee behavior.

- Various retailers have employee training programs and offer incentives for reducing merchandise losses. Others use written policies on ethical behavior that are signed by all personnel, including senior management. Target has enrolled managers at problem stores in a Stock Shortage Institute. Neiman Marcus has shown workers a film with interviews of convicted shoplifters in prison to highlight the problem’s seriousness.

- More retailers are apt to fire employees and prosecute shoplifters involved with theft. Courts are imposing stiffer penalties; in some areas, store detectives are empowered by police to make arrests. In more than 40 states, there are civil restitution laws; shoplifters must pay for stolen goods or face arrests and criminal trials. In most states, fines are higher if goods are not returned or are damaged. Shoplifters must also contribute to court costs.

- Some mystery shoppers are hired to watch for shoplifting, not just to research behavior.

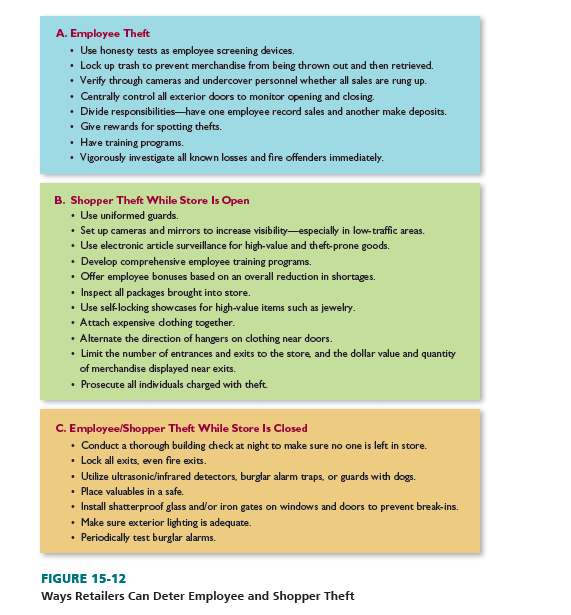

Figure 15-12 presents a list of tactics retailers can use to combat employee and shopper theft, by far the leading causes of losses.

When devising a merchandise security plan, a retailer must assess the plan’s impact on its image, employee morale, shopper comfort, and vendor relations. By setting strict rules for fitting rooms (by limiting the number of garments) or placing chains on very expensive coats, a retailer may cause some shoppers to avoid this merchandise—or visit another store.

4. Reverse Logistics

The term reverse logistics encompasses all merchandise flows from the customer and/or the retailer back through the supply channel. It typically involves items returned because of a shopper’s second thoughts (also called shopper’s remorse), damaged or defective products, or retailer overstocking. In the United States, customer returns alone are estimated by the National Retail Federation at about 8 percent of total retail merchandise sales, with $16 billion of returns being fraudulent. Sometimes, retailers may use closeout firms that buy back unpopular merchandise (at a fraction of the original cost) that suppliers will not take back; these firms then resell the goods at a deep discount. To avoid channel conflicts, conditions for reverse logistics should be specified in advance. U.S. firms spend more than $50 billion per year for handling, transportation, and processing costs associated with returns.27

These are among the decisions that must be made for reverse logistics:

- Under what conditions (the permissible time, the condition of the product, etc.) are customer returns accepted by the retailer and by the manufacturer?

- What is the customer refund policy? Is there a fee for returning an opened package?

- What party is responsible for shipping a returned product to the manufacturer?

- What customer documentation is needed to prove the date of purchase and the price paid?

- How are customer repairs handled (an immediate exchange, a third-party repair, or a refurbished product sent by the manufacturer)?

- To what extent are employees empowered to process customer returns?

5. Inventory Analysis

Inventory status and performance must be analyzed regularly to gauge the success of inventory management. Recent advances in computer software have made such analysis much more accurate and timely. According to surveys of retailers, these are the elements of inventory performance that are deemed most important: gross margin dollars, inventory turnover, gross profit percentage, gross margin return on inventory, the weeks of supply available, and the average in-stock position.

Inventory analysis is discussed further in the next chapter.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Dead composed articles, Really enjoyed looking through.