1. PROBLEM-SOLVING AND DECISION-MAKING TOOLS

The models presented in the previous section can help organizations determine better solutions and make better decisions, provided that they are based on facts. Decisions and solutions based on information that is inaccurate or tainted by personal opinions, exaggeration, or personal agendas are not likely to be optimal, regardless of the problem-solving model used. The information collection step can be made more effective through the use of the total quality tools introduced in Chapter 15.

In today’s competitive environment, organizational decisions and problem responses can no longer be made the way we have been making them for the last 100 years. Today’s business decisions and problem solutions cannot be made without sufficient knowledge of all the relevant factors, which often means that the collective knowledge of the organization must be tapped. At the least, we must be smart in our decision making and problem solving, or we may find ourselves on the path to ruin.

2. DECISION MAKING FOR TOTAL QUALITY

All people make decisions. Some are minor. (What should I wear to work today? What should I have for breakfast?) Some are major. (Should I accept a job offer in another city? Should I buy a new house?) Regardless of the nature of the decision, decision making can be defined as follows:

Decision making is the process of selecting one course of action from among two or more alternatives.

Decision making is a critical task in a total quality setting. Decisions play the same role in an organization that fuel plays in an automobile engine: They keep it running. The work of an organization cannot proceed until decisions are made.

Consider the following example. Because a machine is down, the production department at DataTech Inc. has fallen behind schedule. With this machine down, DataTech cannot complete an important contract on time without scheduling at least 75 hours of overtime. The production manager faces a dilemma. On the one hand, no overtime was budgeted for the project. On the other hand, there is substantial pressure to complete this contract on time because future contracts with this client may depend on it. The manager must make a decision.

In this case, as in all such situations, it is important to make the right decision. But how do managers know when they have made the right decision? In most cases, there is no single right choice. If there were, decision making would be easy. Typically, several alternatives exist, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

For example, in the case of DataTech Inc. the manager had two alternatives: authorize 75 hours of unbudgeted overtime or risk losing future contracts. If the manager authorizes the overtime, his or her company’s profit for the project in question will suffer, but its relationship with a client may be protected. If the manager refuses to authorize the overtime, the company’s profit on this project will be protected, but the relationship with this client may be damaged. These and other types of decisions must be made all the time in the modern workplace.

Managers should be prepared to have their decisions evaluated and even criticized after the fact. Although it may seem unfair to conduct a retrospective critique of decisions that were made during the “heat of battle,” having one’s decisions evaluated is part of accountability, and it can be an effective way to improve a manager’s decision-making skills.

Evaluating Decisions

There are two ways to evaluate decisions. The first is to examine the results. In every case when a decision must be made, there is a corresponding result. That result should advance an organization toward the accomplishment of its goals. To the extent that it does, the decision is usually considered a good decision. Managers have traditionally had their decisions evaluated based on results. However, this is not the only way that decisions should be evaluated. Regardless of results, it is wise also to evaluate the process used in making a decision. Positive results can cause a manager to overlook the fact that a faulty process was used, and in the long run, a faulty process will lead to negative results more frequently than to positive ones.

For example, suppose a manager must choose from among five alternatives. Rather than collecting as much information as possible about each, weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each, and soliciting informed input, the manager chooses randomly. He or she has one chance in five of choosing the best alternative. Such odds occasionally produce a positive result, but typically they don’t. This is why it is important to examine the process as well as the result, not just when the result is negative but also when it is positive.

3. THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS

Decision making is a process. For the purpose of this textbook, the decision-making process is defined as follows:

The decision-making process is a logically sequenced series of activities through which decisions are made.

Numerous decision-making models exist. Although they appear to have major differences, all involve the various steps shown in Figure 16.4 and discussed next.

3.1. Identify or Anticipate the Situation

Anticipating the situation is like driving defensively; never assume anything. Look, listen, ask, and sense. For example, if you hear through the grapevine that a team member’s child has been severely injured and hospitalized, you can anticipate the consequences that may occur. She is likely to be absent, or if she does come to work, her pace may be slowed. The better managers know their employees, technological systems, products, and processes, the better able they will be to anticipate troublesome situations.

3.2. Gather the Facts

Even the most perceptive managers will be unable to anticipate all situations or to understand intuitively what is behind them. For example, suppose a manager notices a “who cares?” attitude among team members. This manager might identify the problem as poor morale and begin trying to improve it. However, he or she would do well to gather the facts first to be certain of what is behind the negative attitudes. The underlying cause(s) could come from a wide range of possibilities: an unpopular management policy, dissatisfaction with the team leader, a process that is ineffective, problems at home, and so on. Using the methods and tools described earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 15, the manager should separate causes from symptoms and determine the root cause of the poor attitude. Only by doing so will the situation be permanently resolved. The inclusion of this step makes possible management by facts—a cornerstone of the total quality philosophy.

It should be noted that the factors that might be at the heart of a bad situation include not only those for which a manager is responsible (policies, processes, tools, training, personnel assignment, etc.) but possibly also the ones beyond the manager’s control (personal matters, regulatory requirements, market and economic influences, etc.). For those falling within the manager’s domain of authority, he or she must make sound, informed decisions based on fact. For the others, the organization has to adapt.

3.3. Consider Alternatives

alternative in light of the facts. The number of alternatives identified in the first step will be limited by several factors. Practical considerations, the manager’s range of authority, and the cause of the situation will all limit a manager’s list of alternatives. After the list has been developed, each entry on it is evaluated. The main criterion against which alternatives are evaluated is the desired outcome. Will the alternative being considered produce the desired result? If so, at what cost?

Cost is another criterion used in evaluating alternatives. Alternatives always come with costs, which might be expressed in financial terms, in terms of employee morale, in terms of the organization’s image, or in terms of a customer’s goodwill. Such costs should be considered when evaluating alternatives. In addition to applying objective criteria and factual data, managers will need to apply their judgment and experience when considering alternatives.

3.4. Choose the Best Alternative, Implement, Monitor, and Adjust

After all alternatives have been considered, one must be selected and implemented, and after an alternative has been implemented, managers must monitor progress and adjust appropriately. Is the alternative having the desired effect? If not, what adjustments should be made? Selecting the best alternative is never a completely objective process. It requires study, logic, reason, experience, and even intuition. Occasionally, the alternative chosen for implementation will not produce the desired results. When this happens and adjustments are not sufficient, it is important for managers to cut their losses and move on to another alternative.

Managers should avoid falling into the ownership trap. This happens when they invest so much ownership in a given alternative that they refuse to change even when it becomes clear the idea is not working. This can happen at any time but is more likely when a manager selects an alternative that runs counter to the advice he or she has received, is unconventional, or is unpopular. The manager’s job is to optimize the situation. Showing too much ownership in a given alternative can impede the ability to do so.

4. OBJECTIVE VERSUS SUBJECTIVE DECISION MAKING

All approaches to decision making fall into one of two categories: objective or subjective. Although the approach used by managers in a total quality setting may have characteristics of both, the goal is to minimize subjectivity and maximize objectivity. The approach most likely to result in a quality decision is the objective approach.

4.1. Objective Decision Making

The objective approach is logical and orderly. It proceeds in a step-by-step manner and assumes that managers have the time to systematically pursue all steps in the decision-making process (see Figure 16.5). It also assumes that complete and accurate information is available and that managers are free (have the authority) to select what they feel is the best alternative.

Measured against these assumptions, it can be difficult to be completely objective when making decisions. Managers don’t always have the luxury of time and complete information. This does not mean that objectivity in decision making should be considered impossible. Managers should be as objective as possible. However, it is important to understand that the day-to-day realities of the workplace may limit the amount of time and information available. When this is the case, objectivity can be affected.

4.2. Subjective Decision Making

Whereas objective decision making is based on logic and complete, accurate information, subjective decision making is based on intuition, experience, and incomplete information. This approach assumes decision makers will be under pressure, short on time, and operating with only limited information. The goal of subjective decision making is to make the best decision possible under the circumstances. In using this approach, the danger always exists that managers might make quick, knee-jerk decisions based on no information and no input from other sources. The subjective approach does not give managers license to make sloppy decisions. If time is short, they should use the little time available to list and evaluate alternatives. If information is incomplete, they should use as much information as is available. Subjective decision making is an anathema in the total quality context, and it should be avoided whenever possible.

5. SCIENTIFIC DECISION MAKING AND PROBLEM SOLVING

As explained in the previous section, sometimes decisions must be made subjectively. However, through good management and leadership, such instances should and can be held to a minimum. One of the keys to success in a total quality setting is using a scientific approach in making decisions and solving problems. One method is to use Joseph M. Juran’s 85/15 rule. Decision makers in a total quality setting should understand this rule. It is one of the fundamental premises underlying the need for scientific decision making.

5.1. Complexity and the Scientific Approach

In the language of scientific decision making, complexity is introduced when improvements are not based on the scientific approach. Several different types of complexity exist, including the following: errors and defects, breakdowns and delays, inefficiency, and variation. The Pareto Principle, explained in Chapter 15, should be kept in mind when attempting to apply the scientific approach.

Errors and Defects Errors cause defects and defects reduce competitiveness. When a defect occurs, one of two things must happen: the part or product must be scrapped altogether, or extra work must be done to correct the defect. Waste or extra work that results from errors and defects adds cost to the product without adding value.

Breakdowns and Delays Equipment breakdowns delay work, causing production personnel either to work overtime or to work faster to catch up. Overtime adds cost to the product without adding value. When this happens, the organization’s competitors gain an unearned competitive advantage. When attempts are made to run a process faster than its optimum rate, an increase in errors is inevitable.

Inefficiency Inefficiency means using more resources (time, material, movement, or something else) than necessary to accomplish a task. Inefficiency often occurs because organizations fall into the habit of doing things the way they have always been done without ever asking why.

Variation In a total quality setting, consistency and predictability are important. When a process runs consistently, efforts can begin to improve it by reducing process variations, of which there are two kinds:

- Common-cause variation is the result of the sum of numerous small sources of natural variation that are always part of the process.

- Special-cause variation is the result of factors that are not part of the process and that occur only in special circumstances, as when a shipment of faulty raw material is used or a new, untrained operator is involved.

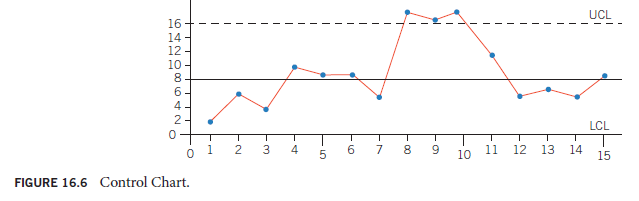

The performance of a process that operates consistently can be recorded and plotted on a control chart such as the one in Figure 16.6. The data points in this figure that fall within the control limits (i.e., between the upper control limit [UCL] and the lower control limit [LCL]) are likely to be related to common causes. The data points that fall outside the control limits are likely to be the results of a special cause of variation. In making decisions about the process in question, it is important to separate common and special causes of variation.

The concept of using control charts and statistical data in problem solving and decision making is discussed in greater depth in Chapter 18.

6. EMPLOYEE INVOLVEMENT IN PROBLEM SOLVING AND DECISION MAKING

Chapter 8 showed how employee involvement and empowerment can improve decision making and problem solving. Employees are more likely to show ownership in a decision or solution they had a part in reaching. Correspondingly, they are more likely to support a decision or solution for which they feel ownership. There are many advantages to be gained from involving employees in decision making and problem solving, as was shown in Chapter 8. There are also factors that, if not understood and properly handled, can lead to problems.

6.1. Advantages of Employee Involvement

Involving employees in decision making and problem solving can have a number of advantages. It can result in a more accurate picture of what the problem really is and a more comprehensive list of potential solution and decision alternatives. It can help managers do a better job of evaluating alternatives and selecting the best one to implement.

Perhaps the most important advantages are gained after the decision is made. Employees who participate in the decision-making or problem-solving process are more likely to understand and accept the decision or solution and have a personal stake in making sure the alternative selected succeeds.

6.2. Potential Problems with Employee Involvement

Involving employees in decision making and problem solving can lead to problems. The major potential problem is that it takes time, and managers do not always have time. Other potential difficulties are that it takes employees away from their jobs and that it can result in conflict among team members. Next to time, the most significant potential problem is that employee involvement can lead to democratic compromises that do not necessarily represent the best decision. In addition, disharmony can result when a decision maker rejects the advice of the group.

Nevertheless, if care is taken, managers can gain all of the advantages, while avoiding the potential disadvantages associated with employee involvement in decision making or problem solving. Several techniques are available to help increase the effectiveness of group involvement. Prominent among these are brainstorming, the nominal group technique (NGT), and the use of teams. Be particularly wary of the dangers of groupthink and groupshift in group decision making, as outlined in Chapter 8.

7. ROLE OF INFORMATION IN DECISION MAKING

Information is a critical element in decision making. Although having accurate, up-to-date, comprehensive information does not guarantee a good decision, lacking such information can guarantee a bad one. The old saying that “knowledge is power” applies in decision making— particularly in a competitive situation. To make decisions that will help their organizations to be competitive, managers need timely, accurate information.

Information can be defined as data that are relevant to the decision-making process that have been converted into a useable format.

Data that are relevant to decision making are those that might have an impact on the decision. Communication is a process that requires a sender, a medium, and a receiver. In this process, information is what is provided by the sender, transmitted by the medium, and received by the receiver. For the purpose of this chapter, decision makers are receivers of information who base decisions at least in part on what they receive.

Advances in technology have ensured that the modern manager can have instant access to information. Computers and telecommunications technology give decision makers a mechanism for collecting, storing, processing, and communicating information quickly and easily. The quality of the information depends on people (or machines) receiving accurate data, entering them into technological systems, and updating them continually. This dependence on accurate information gave rise to the expression “garbage in/garbage out” that is now associated with computer-based information systems. The saying means that information provided by a computer-based system can be no better than the data put into the system.

7.1. Data Versus Information

Data for one person may be information for another. The difference lies in the needs of the individual. Managers’ needs are dictated by the types of decisions they make. For example, a computer printout listing speed and feed rates for a company’s machine tools would contain valuable information for the production manager; the same printout would be just data to the warehouse manager. In deciding on the type of information they need, decision makers should ask themselves these questions:

- What are my responsibilities?

- What are my organizational goals?

- What types of decisions do I have to make relative to these responsibilities and goals?

7.2. Value of Information

Information is a useful commodity. As such, it has value. Its value is determined by the needs of the people who will use it and the extent to which the information will help them meet their needs. Information also has a cost. Because it must be collected, stored, processed, continually updated, and presented in a useable format when needed, information can be expensive. This fact requires managers to weigh the value of information against its cost when deciding what information they need to make decisions. It makes no sense to spend $100 collecting the information to make a $10 decision.

7.3. Amount of Information

An old saying holds that a manager can’t have too much information. This is no longer true. With advances in information technologies, not only can managers have too much information, but also they frequently do. This phenomenon has come to be known as information overload, the condition that exists when people receive more information than they can process in a timely manner. The phrase “in a timely manner” means in time to be useful in decision making (see Figure 16.7).

To avoid information overload, apply a few simple strategies. First, examine all regular reports received. Are they really necessary? Do you receive daily or weekly reports that would meet your needs just as well if provided on a monthly basis? Do you receive regular reports that would meet your needs better as exception reports? In other words, would you rather receive reports every day that say everything is all right or occasional reports when there is a problem? The latter approach is reporting by exception and can cut down significantly on the amount of information that managers must absorb.

Another strategy for avoiding information overload is formatting for efficiency. This involves working with personnel who provide information. If your organization has a management information systems (MIS) department or an information technology (IT) department, ensure that reports are formatted for your convenience rather than theirs (MIS will be discussed in the next section). Decision makers should not have to wade through reams of computer printouts to locate the information they need. Nor should they have to become bleary-eyed reading rows and columns of tiny figures. Work with MIS personnel to develop an efficient report form that meets your needs. Also, have that information presented graphically whenever possible.

Finally, make use of online, on-demand information retrieval. In the modern workplace, most reports are computer generated. Rather than relying on periodic printed reports, learn to retrieve information from the MIS database when you need it (on demand) using a computer terminal or a networked personal computer (online).

7.4. Using Management Information Systems

The previous section contained references to management information systems (MIS) and MIS personnel. Note: For our purposes, consider MIS and IT to be interchangeable.

A management information system (MIS) is a system used to collect, store, process, and present information used by managers in decision making.

In the modern workplace, a management information system is typically a computer-based system. A management information system has three major components; hardware, software, and people. Hardware consists of the computer, all of the peripheral devices for interaction with the computer, and output devices such as printers and display screens.

Software is the component that allows the computer to perform specific operations and process data. It consists primarily of computer programs but also includes the database, files, and manuals that explain operating procedures. Systems software controls the basic operation of the system. Applications software controls the processing of data for specific computer applications (word processing, databases, computer-assisted planning, spreadsheets, etc.).

A database is a broad collection of data from which specific information can be drawn. For example, a company might have a personnel database in which many different items of information about its employees are stored. From this database can be drawn a variety of different reports—such as printouts of all employees in order of employment date, by job classification, or by ZIP code. Data are kept in electronic files stored under specific groupings or file names.

The most important component is the people component. It consists of the people who manage, operate, maintain, and use the system. Managers who depend on a management information system for part of the information needed to make decisions are users.

Managers should not view a management information system as the final word in information. Such systems can do an outstanding job of providing information about predictable matters that are routine in nature. However, many of the decisions managers have to make concern problems that are unpredictable (or that simply have not been predicted) and for which data are not tracked. For this reason, it is important to have sources other than the management information system from which to draw information.

8. CREATIVITY IN DECISION MAKING

The pressures of a competitive marketplace are making it increasingly important for organizations to be flexible, innovative, and creative in decision making. To survive in an unsure, rapidly changing marketplace, organizations must be able to adjust rapidly and change directions quickly. To do so requires creativity at all levels of the organization.

8.1. Creativity Defined

Like leadership, creativity has many definitions, and viewpoints vary about whether creative people are born or made. In modern organizations, creativity can be viewed as an approach to problem solving and decision making that is imaginative, original, and innovative. Developing such perspectives requires that decision makers have knowledge and experience regarding the issue in question.

8.2. Creative Process

The creative process proceeds in stages: preparation, incubation, insight, and verification.3 What takes place in each of these stages is summarized as follows:

- Preparation involves learning, gaining experience, and collecting or storing information in a given area. Creative decision making requires that the people involved be prepared.

- Incubation involves giving ideas time to develop, change, grow, and solidify. Ideas incubate while decision makers get away from the issue in question and give the mind time to sort things out. Incubation is often a function of the subconscious mind.

- Insight follows incubation. It is the point in time when a potential solution falls in place and becomes clear to decision makers. This point is sometimes seen as a moment of inspiration. However, inspiration rarely occurs without having been preceded by perspiration, preparation, and incubation.

- Verification involves reviewing the decision to determine whether it will actually work. At this point, traditional processes such as feasibility studies and cost-benefit analysis are used.

8.3. Factors That Inhibit Creativity

A number of factors can inhibit creativity. Some of the more prominent of these follow:4

- Looking for just one right answer. Seldom is there just one right solution to a problem.

- Focusing too intently on being logical. Creative solutions sometimes defy logic and conventional wisdom.

- Avoiding ambiguity. Ambiguity is a normal part of the creative process. This is why the incubation step is so important.

- Avoiding risk. When organizations don’t seem to be able to find a solution to a problem, it often means decision makers are unwilling to give an idea a chance.

- Forgetting how to play. Adults sometimes become so serious they forget how to play. Playful activity can stimulate creative ideas.

- Fearing rejection or looking foolish. Nobody likes to look foolish or feel rejection. This fear can cause people to hold back what might be creative solutions.

- Saying “I’m not creative.” People who decide they are uncreative will be. Any person can think creatively and can learn to be even more creative.

8.4. Helping People Think Creatively

In the age of high technology and global competition, creativity in decision making and problem solving is critical. Although it is true that some people are naturally more creative than others, it is also true that any person can learn to think creatively. In the modern workplace, the more people who think creatively, the better. The following strategies will help employees think creatively:5

- Idea vending. This is a facilitation strategy. It involves reviewing literature in the field in question and compiling files of ideas contained in the literature. Periodically, circulate these ideas among employees as a way to get people thinking. This will facilitate the development of new ideas by the employees. Such an approach is sometimes called stirring the pot.

- Listening. One of the factors that causes good ideas to fall by the wayside is poor listening. Managers who are perpetually too hurried to listen to employees’ ideas do not promote creative thinking. On the contrary, such managers stifle creativity. In addition to listening to the ideas, good and bad, of employees, managers should listen to the problems employees discuss in the workplace. Each problem is grist for the creativity mill.

- Idea attribution. A manager can promote creative thinking by subtly feeding pieces of ideas to employees and encouraging them to develop the idea fully. When an employee develops a creative idea, he or she gets full attribution and recognition for the idea. Time may be required before this strategy pays off, but with patience and persistence it can help employees become creative thinkers.

How does a football team that is no better than its opponent beat that opponent? Often the key is more creative game planning, play calling, and defense. This phenomenon also occurs in the workplace every day. The organization that wins the competition in the marketplace is often the one that is the most creative in decision making and problem solving.

Source: Goetsch David L., Davis Stanley B. (2016), Quality Management for organizational excellence introduction to total Quality, Pearson; 8th edition.

good post.Never knew this, thankyou for letting me know.