1. Thinking Strategically

Strategic management is considered a specific type of planning. Strategic planning in for-profit business organizations typically pertains to competitive actions in the market- place. In nonprofit organizations such as the Red Cross and the Salvation Army, strategic planning pertains to events in the external environment. The final responsibility for strategy rests with top managers and the chief executive.

For an organization to succeed, the CEO must be actively involved in making the tough choices and trade-offs that define and support strategy.56 In addition, senior executives at companies such as General Electric, 3M, and Johnson & Johnson want middle- and low- level managers to think strategically. Some companies also are finding ways to get front- line workers involved in strategic thinking and planning.

Strategic thinking means to take the long-term view and to see the big picture, includ- ing the organization and the competitive environment, and to consider how they fit together. Understanding the strategy concept, levels of strategy, and strategy formulation versus implementation is an important start toward strategic thinking.

1.1. WHAT IS STRATEGIC MANAGEMENT?

Strategic management is the set of decisions and actions used to formulate and implement strategies that will provide a competitively superior fit between the organization and its environment so as to achieve organizational goals.57 Managers ask questions such as: What changes and trends are taking place in the competitive environment? Who are our compet- itors, and what are their strengths and weaknesses? Who are our customers? What prod- ucts or services should we offer, and how can we offer them most efficiently? What does the future hold for our industry, and how can we change the rules of the game? Answers to these questions help managers make choices about how to position their organizations in the environment with respect to rival companies.58

Superior organizational performance is not a matter of luck. It is determined by the choices managers make. Top executives use strategic management to define an overall direction for the organization—the firm’s grand strategy.

1.2. PURPOSE OF STRATEGY

Within the overall grand strategy of an organization, executives define an explicit strategy, the plan of action that describes resource allocation and activities for dealing with the environment, achieving a competitive advantage, and attaining the organization’s goals.

Competitive advantage refers to what sets the organization apart from others and provides it with a distinctive edge for meeting customer needs in the marketplace. The essence of formulating strategy is to choose how the organization will be different.59

Managers make decisions about whether the company will perform different activities or will execute similar activities differently than competitors do. Strategy necessarily changes over time to fit environmental conditions, but to remain competitive, companies develop strategies that emphasize core competencies, develop synergy, and create value for customers.

Core Competence. A company’s core competence is something the organiza- tion does especially well in comparison to its competitors. A core competence represents a competitive advantage because the company acquires expertise that competitors do not have. A core competence may be in the area of superior research and development, expert technological know-how, process efficiency, or exceptional customer service.60

At VF, a large apparel company that owns Vanity Fair, Nautica, Wrangler, and The North Face, strategy focuses on the company’s core competencies of operational efficiency and merchandising know-how. When VF bought The North Face, for example, its distri- bution systems were so poor that stores were getting ski apparel at the end of winter and camping gear at the end of summer. The company’s operating profit margin was minus 35 percent. Managers at VF revamped The North Face’s sourcing, distribution, and finan- cial systems, and within 5 years doubled sales to $500 million and improved profit margins to a healthy 13 percent. “For VF it was easy, and it’s not easy for everybody” one retail analyst said, referring to the company’s application of its core competencies.61

Gaylord Hotels, which has large hotel and conference centers in several states, as well as the Opryland complex near Nashville, Tennessee, thrives based on a strategy of superior service for large group meetings.62 Robinson Helicopter succeeds through superior techno- logical know-how for building small, two-seater helicopters used for everything from police patrols in Los Angeles to herding cattle in Australia.63In each case, leaders identified what their company does especially well and built strategy around it.

Synergy. Organizational parts interacting to produce a joint effect that is greater than the sum of the parts acting alone is called synergy. The organization may attain a special advantage with respect to cost, market power, technology, or management skill. When managed properly, synergy can create additional value with existing resources, which provides a big boost to the bottom line.64

Synergy was one motivation for the FedEx acquisition of Kinko’s Inc. in 2004, to bring together package delivery with full-service counters. But the merger has not gone as well as planned and the company has retooled its strategy by focusing on different customers (small- and medium-sized businesses, mobile professionals and convention centers/hotels). In addition, more stores are being opened. While the company had only opened about 20 stores a year previously, in 2007 it opened 100 and plans to double and triple that in the next two years.65

Synergy also can be obtained through good relations with suppliers or by strong alliances among companies. Yahoo!, for example, uses partnerships, such as a deal with Verizon Communications, to boost its number of paying subscribers to nearly 12 million.66

Delivering Value. Delivering value to the customer is at the heart of strategy.

Value can be defined as the combination of benefits received and costs paid.

Managers help their companies create value by devising strategies that exploit core com- petencies and attain synergy. To compete with the rising clout of satellite television, for example, cable companies such as Adelphia and Charter Communications are trying to provide better value with cable value packages that offer a combination of basic cable, digital premium channels, video on demand, and high-speed Internet for a reduced cost.

The Swedish retailer IKEA has become a global cult brand by offering beautiful, functional products at modest cost, thus delivering superior value to customers.67

2. The Strategic Management Process

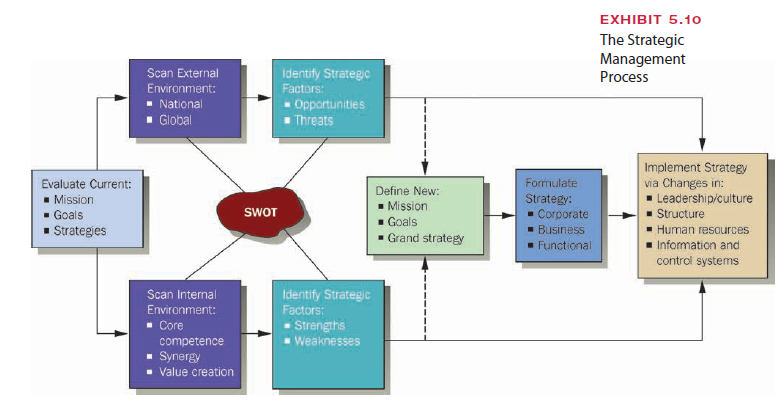

The overall strategic management process is illustrated in Exhibit 5.10. It begins when executives evaluate their current position with respect to mission, goals, and strategies. Then they scan the organization’s internal and external environments and identify strategic factors that might require change. Internal or external events might indicate a need to redefine the mission or goals or to formulate a new strategy at the corporate, business, or functional level. The final stage in the strategic management process is to implement the new strategy.

2.1. STRATEGY FORMULATION VERSUS IMPLEMENTATION

Strategy formulation involves the planning and decision making that lead to establish- ment of the firm’s goals and development of a specific strategic plan.68 Strategy formulation may include assessing the external environment and internal problems and integrating the results into goals and strategy. This process is in contrast to strategy implementation, which is the use of managerial and organizational tools to direct resources toward accomplishing strategic results.69 Strategy implementation is the administration and execution of the strategic plan. Managers may use persuasion, new equipment, changes in organizational structure, or a revised reward system to ensure that employees and resources are utilized to make formulated strategy a reality.

2.2. SITUATION ANALYSIS

Formulating strategy often begins with an assessment of the internal and external factors that will affect the organization’s competitive situation. Situation analysis typically includes a search for SWOT—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—that affect organizational performance. Situation analysis is important to all companies but is crucial to those considering globalization because of the diverse environments in which they will operate.

External information about opportunities and threats may be obtained from a variety of sources, including customers, government reports, professional journals, suppliers, bankers, friends in other organizations, consultants, and association meetings. Many firms hire special scanning organizations to provide them with newspaper clippings, Internet research, and analyses of relevant domestic and global trends. In addition, many companies are hiring competitive intelligence professionals to scope out competitors, as we discussed in Chapter 2.

Executives acquire information about internal strengths and weaknesses from a variety of reports, including budgets, financial ratios, profit-and-loss statements, and surveys of employee attitudes and satisfaction. Managers spend 80 percent of their time giving and receiving information. Through frequent face-to-face discussions and meetings with people at all levels of the hierarchy, executives build an understanding of the company’s internal strengths and weaknesses.

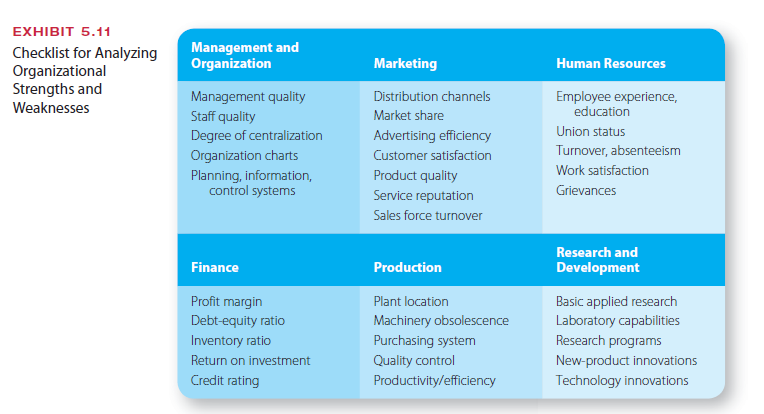

Internal Strengths and Weaknesses. Strengths are positive internal characteristics that the organization can exploit to achieve its strategic performance goals. Weaknesses are internal characteristics that might inhibit or restrict the organization’s per- formance. Some examples of what executives evaluate to interpret strengths and weak- nesses are given in Exhibit 5.11.The information sought typically pertains to specific func- tions such as marketing, finance, production, and R&D. Internal analysis also examines overall organization structure, management competence and quality, and human resource characteristics. Based on their understanding of these areas, managers can determine their strengths or weak- nesses compared to other companies.

External Opportunities and Threats. Threats are characteristics of the external environment that may prevent the organization from achieving its strategic goals. Opportunities are characteristics of the external envi- ronment that have the potential to help the organization achieve or exceed its strategic goals. Executives evaluate the external environment with information about the nine sectors described in Chapter 2.

The task environment sectors, the most relevant to strategic behavior, include the behavior of competitors, customers, suppliers, and the labor supply. The general environment contains those sectors that have an indirect influence on the organization but nevertheless must be understood and incorporated into strategic behavior. The general environment includes technological develop- ments, the economy, legal-political and international events, and sociocultural changes. Additional areas that might reveal opportunities or threats include pressure groups, interest groups, creditors, natural resources, and poten- tially competitive industries.

3. Formulating Business-Level Strategy

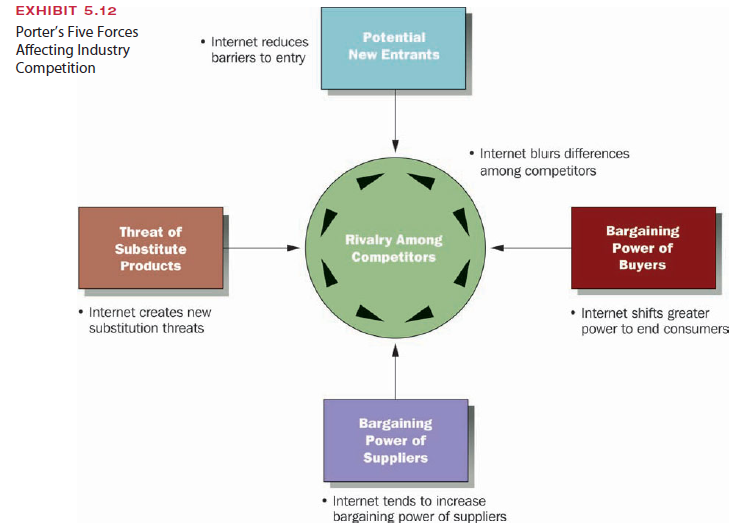

One model for formulating strategy, Porter’s competitive strategies, provides a framework for business unit competitive action. Michael E. Porter studied a number of business organizations and proposed that business-level strategies are the result of five competitive forces in the company’s environment.71 More recently he examined the impact of the Internet on business-level strategy.72 New web-based technology is influencing industries in both positive and negative ways, and understanding this impact is essential for managers to accurately analyze their competitive environments and design appropriate strategic actions.

Exhibit 5.12 illustrates the competitive forces in a company’s environment and indicates some ways that Internet technology is affecting each area. These forces help to determine a company’s position vis-à-vis competitors in the industry environment.

- Potential new entrants. Examples of two potential barriers to entry that can keep out new competitors are capital requirements and economies of scale. Entering the automobile industry, for instance, is far more costly than starting a specialized mail-order business. In general, Internet technology has made it much easier for new companies to enter an industry by curtailing the need for organizational elements such as an established sales force, physical assets such as buildings and machinery, and access to existing supplier and sales channels.

- Bargaining power of buyers. Informed customers become empowered customers. The Internet provides easy access to a wide array of information about products, services, and competitors, thereby greatly increasing the bargaining power of end consumers. For example, a customer shopping for a car can gather extensive information about various options, such as wholesale prices for new cars or average value for used vehicles, detailed specifications, repair records, and even whether a used car has ever been in- volved in an accident.

- Bargaining power of suppliers. The concentration of suppliers and the availability of sub- stitute suppliers are significant factors in determining supplier power. The sole supplier of engines to a manufacturer of small airplanes will have great power, for example. The impact of the Internet in this area can be both positive and negative. That is, procure- ment over the Web tends to give a company greater power over suppliers, but the Web also gives suppliers access to more customers, as well as the ability to reach end users. Overall, the Internet tends to raise the bargaining power of suppliers.

- Threat of substitute products. The power of alternatives and substitutes for a company’s product may be affected by changes in cost or in trends, such as increased health consciousness, which deflect buyer loyalty. Companies in the sugar industry suffered from the growing popularity of sugar substitutes. Manufacturers of aerosol spray cans lost business as environmentally conscious consumers chose other products. The Internet created threats of new substitutes by enabling new approaches to meeting customer needs. For example, offers of low-cost airline tickets over the Internet hurt traditional travel agencies.

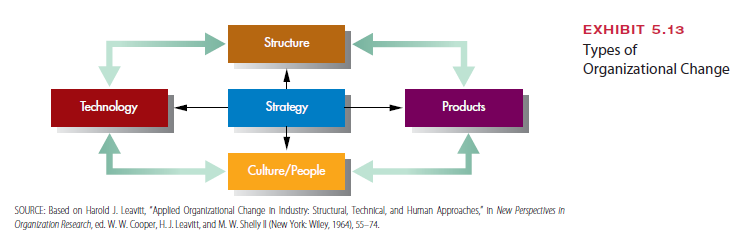

- Rivalry among competitors. As illustrated in Exhibit 5.13, rivalry among competitors is influenced by the preceding four forces, as well as by cost and product differentiation. With the leveling force of the Internet and information technology, many companies have more difficulty finding ways to distinguish themselves from their competitors, which intensifies rivalry.

Porter referred to the “advertising slugfest” when describing the scrambling and jockey- ing for position that often occurs among fierce rivals within an industry. Famous examples include the competitive rivalry between Pepsi and Coke, between UPS and FedEx, and between Home Depot and Lowe’s. The rivalry between Gillette Company (which has been purchased by Procter & Gamble) and Schick, the number two maker of razors (now owned by Energizer), may become just as heated. Although Gillette is still way ahead, introduc- tion of the Schick Quattro and a massive advertising campaign helped Schick’s 2003 sales grow 149 percent while Gillette’s razor sales slipped. In the two years after the Quattro was introduced, Schick’s market share for replacement blades jumped 6 percent while Gillette’s declined. In the fall of 2005, Schick brought out a battery-powered version of Quattro, aimed directly at stealing market share from Gillette’s M3Power. Gillette took the next shot with its announcement of the new Fusion five-blade razor.73

3.1. COMPETITIVE STRATEGIES

In finding its competitive edge within these five forces, Porter suggests that a company can adopt one of three strategies: differentiation, cost leadership, or focus. The organizational characteristics typically associated with each strategy are summarized in Exhibit 5.14.

Differentiation. The differentiation strategy involves an attempt to distinguish the firm’s products or services from others in the industry. The organization may use ad- vertising, distinctive product features, exceptional service, or new technology to achieve a product perceived as unique. The differentiation strategy can be profitable because custom- ers are loyal and will pay high prices for the product. Examples of products that have bene- fited from a differentiation strategy are Harley-Davidson motorcycles, Snapper lawn equipment, and Gore-Tex fabrics, all of which are perceived as distinctive in their markets.

When lawn equipment maker Simplicity bought Snapper, for example, one of the first things that executives did was to pull Snapper products out of Wal-Mart. Whereas most manufacturers do whatever they can to sell through the giant retailer, Simplicity’s managers recognized that selling mowers at Wal-Mart was incompatible with their strategy, which emphasizes quality, dependability, durability, and cachet rather than high volume and low cost. Customers can buy a lawn mower at Wal-Mart for less than a hundred bucks, but the least expensive Snapper is about $350 and is built to last for decades.74 Service companies such as Starbucks, Whole Foods Market, and IKEA also use a differentiation strategy.

Companies that pursue a differentiation strategy typically require strong marketing abilities, a creative flair, and a reputation for leadership.75A differentiation strategy can reduce rivalry with competitors if buyers are loyal to a company’s brand. Successful differ- entiation also can reduce the bargaining power of large buyers by making other products less attractive, which also helps the firm fight off threats of substitute products. In addition, differentiation erects entry barriers in the form of customer loyalty, which a new entrant into the market would have difficulty overcoming.

Cost Leadership. With a cost leadership strategy, the organization aggres- sively seeks efficient facilities, pursues cost reductions, and uses tight cost controls to pro- duce products more efficiently than competitors do. A low-cost position means that the company can undercut competitors’ prices and still offer comparable quality and earn a reasonable profit. Comfort Inn and Motel 6 are examples of low-priced alternatives to Four Seasons and Marriott. Enterprise Rent-A-Car is a low-priced alternative to Hertz.

Being a low-cost producer provides a successful strategy to defend against the five competitive forces in Exhibit 5.13. For example, the most efficient, low-cost company is in the best position to succeed in a price war while still making a profit. Likewise, the low-cost producer is protected from powerful customers and suppliers because customers cannot find lower prices elsewhere and other buyers would have less slack for price negotiation with suppliers. If substitute products or new entrants come onto the scene, the low-cost producer is better positioned than higher-cost rivals to prevent loss of market share. The low price acts as a barrier against new entrants and substitute products.76

Focus. With a focus strategy, the organization concentrates on a specific regional market or buyer group. The company uses either a differentiation approach or a cost lead- ership approach, but only for a narrow target market. Save-A-Lot, described earlier, uses a focused cost leadership strategy, placing its stores in low-income areas. Another example is low-cost leader Southwest Airlines, which was founded in 1971 to serve only three cities— Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio—and didn’t fly outside of Texas for the first 8 years of its history. Managers aimed for controlled growth, gradually moving into new geographic areas where Southwest could provide short-haul service from city to city. Through a focus strategy, Southwest was able to grow rapidly and expand to other markets.77

Edward Jones Investments, a St. Louis-based brokerage house, uses a focused differen- tiation strategy, building its business in rural and small-town America and providing cli- ents with conservative, long-term investment advice. According to management consultant Peter Drucker, the safety-first orientation means that Edward Jones delivers a product “that no Wall Street house has ever sold before: peace of mind.”78

Managers think carefully about which strategy will provide their company with its competitive advantage. Gibson Guitar Corp., famous in the music world for its innova- tive, high-quality products, found that switching to a low-cost strategy to compete against Japanese rivals such as Yamaha and Ibanez actually hurt the company. When managers realized that people wanted Gibson products because of its reputation, not its price, the company went back to a differentiation strategy and invested in new technol- ogy and marketing.79

In his studies, Porter found that some businesses did not consciously adopt one of these three strategies and were stuck with no strategic advantage. Without a strategic advantage, businesses earned below-average profits compared to those that used differentiation, cost leadership, or focus strategies. Similarly, a five-year study of management practices in hundreds of businesses, referred to as the Evergreen Project, found that a clear strategic di- rection was a key factor that distinguished winners from losers.80

Because the Internet is having such a profound impact on the competitive environment in all industries, companies now, more than ever, must distinguish themselves through careful strategic positioning in the marketplace.81 The Internet tends to erode both cost leadership advantages and differentiation advantages by providing new tools for managing costs and giving consumers greater access to comparison shopping. Nevertheless, managers can find ways to incorporate the Internet into their strategic approaches in a way that pro- vides unique value to customers in an efficient way. Sears, for example, uses the Web to showcase its line of Kenmore appliances, building the brand’s reputation by providing de- tailed information in a relatively inexpensive way.82

3.2. PARTNERSHIP STRATEGIES

So far we have been discussing strategies that are based on how to compete with other companies. An alternative approach to strategy emphasizes collaboration. In some situa- tions, companies can achieve competitive advantage by cooperating with other firms rather than competing with them. Partnership strategies are becoming increasingly popular as firms in all industries join with other organizations to promote innovation, expand markets, and pursue joint goals. At one time, partnering was a strategy adopted primarily by small firms that required greater marketing muscle or international access. Today, however, it has become a way of life for most companies, large and small. The question no longer is whether to collaborate but, rather, where, how much, and with whom to collaborate.83

Competition and cooperation often are present at the same time. Procter & Gamble and Clorox are fierce rivals in cleaning products and water purification, but both com- panies profited by collaborating on a new plastic wrap. P&G researchers invented a wrap that seals tightly only where it is pressed, but P&G didn’t have a plastic wrap category. Managers negotiated a joint venture with Clorox to market the wrap under the well-established Glad brand name, and Glad Press & Seal became one of the company’s most popular products. The two competitors continued the collaboration with the introduction of Glad Force Flex trash bags, which make use of a stretchable plastic invented in P&G’s labs.84

The Internet is both driving and supporting the move toward partnership thinking. The ability to rapidly and smoothly conduct transactions, commu- nicate information, exchange ideas, and Golfsmith International, are gaining a stronger online presence by partnering with Amazon. com. Amazon maintains the site and processes the orders, and the retailers fill the orders from their own warehouses. The arrangement gives Amazon a new source of revenue and frees the retailers to focus on their bricks-and-mortar business while also gaining new customers online.86

Mutual dependencies and partnerships have become a fact of life, but the extent of col- laboration varies. Organizations can choose to build cooperative relationships in many ways, such as through preferred suppliers, strategic business partnering, joint ventures, or mergers and acquisitions. Exhibit 5.14 illustrates these major types of strategic business relationships according to the amount of collaboration involved. With preferred supplier relationships, a company such as Wal-Mart, for example, develops a special relationship with a key supplier such as Procter & Gamble, which eliminates intermediaries by sharing complete information and reducing the costs of salespeople and distributors. Preferred sup- plier arrangements provide long-term security for both organizations, but the level of col- laboration is relatively low.

Strategic business partnering requires a higher level of collaboration. Five of the largest hotel chains—Marriott International, Hilton Hotels Corp., Six Continents, Hyatt Corp., and Starwood Hotels and Resorts Worldwide Inc.—partnered to create their own website, Travelweb.com, to combat the growing power of intermediaries such as Expedia and Hotels. com. According to one senior vice president, the hotels felt a need to “take back our room product, and . . . sell it the way we want to sell it and maximize our revenues.” At the same time, some chains are striving to build more beneficial partnerships with the third-party brokers.87

Still more collaboration is reflected in joint ventures, which are separate entities

created with two or more active firms as sponsors. For example, International Truck and Engine Corporation has a joint venture with Ford Motor Company to build midsized trucks and diesel engine parts.88 MTV Networks originally was created as a joint venture of Warner Communications and American Express. In a joint venture, organizations share the risks and costs associated with the new venture.

Mergers and acquisitions represent the ultimate step in collaborative relationships. U.S. business has been in the midst of a tremendous merger and acquisition boom. Consider the frenzied deal-making in the telecom industry alone. Sprint acquired Nextel, and Verizon Communications purchased MCI. SBC Communications Inc. acquired AT&T and took over the storied brand name, then announced plans to buy BellSouth, making AT&T once again the giant in the telecommunications industry.89

Using these various partnership strategies, today’s companies simultaneously embrace competition and cooperation. Few companies can go it alone under the constant onslaught of international competition, changing technology, and new regulations. Most businesses choose a combination of competitive and partnership strategies that add to their overall sustainable advantage.90

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Hey, you used to write excellent, but the last several posts have been kinda boring?K I miss your super writings. Past few posts are just a little out of track! come on!

Nice post. I learn something more challenging on different blogs everyday. It will always be stimulating to read content from other writers and practice a little something from their store. I’d prefer to use some with the content on my blog whether you don’t mind. Natually I’ll give you a link on your web blog. Thanks for sharing.