Governments use export controls for a variety of reasons. Such controls are often intended to achieve certain desired political and economic objectives. The first U.S. export control was introduced in 1775, when the Continental Congress outlawed the export of goods to Great Britain. Since then, the United States has restricted exports to certain countries through legislation such as the Embargo Act, the Trading with the Enemy Act, the Neutrality Act, and the Export Control Act.

The Export Control Act of 1949 represents the first comprehensive export control program enacted in peacetime. Export controls prior to this time were almost exclusively devoted to the prohibition or curtailment of arms exports (arms embargoes). The 1949 legislation was primarily intended to curtail the export of certain commodities to Communist nations during the Cold War era. Export controls were thus allowed for reasons of national security, foreign policy and short supply. Given America’s dominant economic position in the postwar era, it provided leadership in international economic relations and pursued an active foreign policy (Moskowitz, 1996; Stenger, 1984).

In 1969, the often stringent and far-reaching restrictions were curtailed, and a new law (Export Administration Act, 1969) attempted to balance the need for export controls against the adverse effects of an overly comprehensive export control system on the country’s economy. This came at a time when the United States was losing ground to other nations in economic performance, such as balance of trade and exports. The overvalued dollar and inflation, for example, had adversely affected U.S. competitiveness in foreign markets and shrank its trade surplus from $6.8 billion in 1964 to a mere $400 million in 1969. The promotion of exports was considered essential to improving the country’s declining trade surplus and overall competitiveness as well as to reducing the growing unemployment. The general trend in 1969 and thereafter has been to ease and/or strengthen the position of exporters and increase the role of Congress in implementing export control policy. Some examples follow:

- The Equal Export Opportunity Act of 1972 curtailed the use of export controls if the product (that is subject to such restrictions) was available from sources outside the United States in comparable quality and quantity. This was because export controls would be ineffective if certain commodities were available from foreign sources. A 1977 amendment prohibited the president from imposing export controls without providing adequate evidence with regard to the product’s importance to U.S. national security interests. In the event that the president decided to prohibit or control exports, the law required that he negotiate with other countries to eliminate foreign availability. The scope of presidential authority to regulate U.S. foreign transactions, including the imposition of export controls, was restricted to wartime only. A statute (the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, 50 U.S. Code 1701 4 seq.) was also passed to regulate presidential powers in the area of export controls during national emergencies. As of 1998, restrictions based on national emergencies have been imposed against Angola, Iraq, Libya, North Korea, Iran, Haiti, and the former Yugoslavia. In short, the president can impose export controls outside emergency and wartime periods only upon extensive review and consultation with Congress.

- In 1977, Congress introduced limitations on the power of the executive branch to prohibit or curtail agricultural exports. Any prohibition of such exports was considered ineffective without the approval of Congress by concurrent resolution.

- The 1979 Export Administration Act (EAA) also emphasized the important contribution of exports to the U.S. economy and acknowledged the necessity of balancing the need for trade and exports against national security interests. The law also gave legal effect to the agreement of the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM), established in 1949 to coordinate controls on exports of technology to Communist countries. It was dissolved in 1994. COCOM was primarily intended to control three categories of goods: conventional arms, nuclear-related items, and dual-use items. The third category was the most controversial since it restricted normal commerce and limited trade in goods and technologies that have both civilian and military applications (Hunt, 1983).

- A 1985 amendment to the Export Administration Act further restricted the power of the president to impose foreign policy controls that interfere with contracts entered into before the decision to restrict exports, except under very specific circumstances. Congress also established validated licenses for multiple exports, allowing exporters to make successive shipments of the same goods under a single license, waived licensing requirements for certain low-tech goods exports to COCOM nations, and shortened by one third the time period for issuing licenses for exports to non-COCOM members. In view of certain international incidents, such as the downing, in 1983, of a Korean Airlines aircraft by the former Soviet Union, the law, however, tightened export controls on the acquisition of critical military goods and technology by the former Soviet Union and its allies.

Export controls were originally intended to be used against Communist countries. However, with the end of the Cold War, no longer was there a clearly defined single adversary, and it became necessary to adjust the system of export controls to take into account the new reality in international relations. An increasingly global economy also presented new challenges for managing export controls. The growing number of global suppliers of high technology and defense-related items, increased levels of global R&D, dissemination of dual-use technologies, and the existence of divergent views among Western countries militated in favor of liberalization of export controls. Prior to September 11, 2001, substantial liberalization of controls had taken place in many areas, such as high-performance computers and telecommunications. Export controls were aimed at, inter alia, restricting a narrow range of transactions that could assist in the development of weapons of mass destruction by certain countries. The control system essentially focused on a small group of critical goods and technology and on specific end uses and end users, in addition to certain “reckless” nations that must be stopped from acquiring weapons of mass destruction. The new multilateral arrangement that was developed after COCOM, the Wassenaar arrangement (1990), also focused on transfers of conventional arms and dual-use goods and technology. However, it is not binding, and member countries implement the controls solely at their own discretion. Unlike the situation under COCOM, Wasenaar members do not have veto power over one another’s exports and do not have an agreed list of restricted countries. Furthermore, the agreement does not require notification regarding projected exports prior to shipment. Even though Wasenaar member countries agree on the need to avoid destabilizing accumulations of weapons and dual-use items in countries of concern, they disagree about which countries are states of concern (particularly China) and what constitutes a destabilizing transfer (Corr, 2003).

After the events of September 11, 2001, the U.S. government introduced certain restrictions on exports. First, it prohibits the conduct of business with any group whose name appears on the lists of denied persons maintained by the Office of Foreign Assets Control. The list includes the names of terrorists, individuals, and companies associated with terrorists or terrorist organizations. Second, a deemed export license is required before foreign nationals engaged in research in the United States (at a U.S. university campus) receive technology or technical data on the use of export-controlled equipment or materials. For a deemed license to be required, the information being conveyed must both involve controlled equipment (and other materials) and equipment that is not publicly available. The fundamental research exclusion applies to information in the United States that is broadly shared with the scientific community and not restricted for proprietary reasons or specific national security concerns. Third, the U.S. Commerce Department bureau responsible for export controls on dual-use goods and technologies changed its name from the Bureau of Export Administration (BXA) to the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), a change that reflected the connection between trade and security. A focus has also been placed on controlling the export of weapons of mass destruction to hostile countries. Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, many Western governments do not permit risky exports, while approving legitimate ones more efficiently (Walsh, 2002). (See International Perspective 15.3 for multilateral export controls.) In 2011, BIS processed 25,093 export license applications valued at $90 billion (U.S.) and approved 86 percent, returned 13 percent, and denied about 1 percent of the applications. Its average processing time for review of license applications is about thirty days. The largest category of applications concerns the export of crude oil (about $65 billion), followed by chemical manufacturing and equipment ($343 million in 2011).

Export Administration Regulations

Administration of Export Controls

The Export Administration Regulations (EAR) are designed to implement the Export Administration Act (EAA) of 1979 and subsequent amendments. The EAR is administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). The EAR is not permanent legislation. When it lapsed, presidential executive orders under the Emergency Powers Act directed and authorized the continuation of the EAR. The regulations also implement antiboycott law provisions.

U.S. export controls are primarily imposed for the following reasons (EAR, part 742):

- Protect national security: A major goal of controls is to restrict the export/re-export of items that would make a significant contribution to the military potential of any other country and that would prove detrimental to the national security of the United States. This includes the exports of high-performance computers, software, and technology to particular destinations, end users, and end uses. The list of controlled countries (Country Group D-1) includes Albania, China, Laos, Russia, and Vietnam. The lists of countries and products are periodically reviewed and revised to take into account current developments. The national security-based control list is consistent with the control list of the Wasenaar agreement. National security controls are subject to foreign availability determination; that is, items must be decontrolled if they are available to controlled countries from sources outside the United States in sufficient quantity and comparable quality. In 2009, for example, export controls were lifted on night-vision cameras but tightened on higher-end thermal imaging cameras (Fergusson, 2009).

- Furtherforeignpolicygoals: An important goal of controls on the export/re-export of goods and technology is to further the foreign policy objectives of the United States, that is, to support human rights, regional stability, and antiterrorism policies. It is also used to implement unilateral or international sanctions such as those imposed by the United Nations or the Organization of American States. This includes adherence to multilateral nonproliferation agreements in the areas of chemical and biological weapons, nuclear weaponry, and missile technology. Foreign policy controls must be renewed on an annual basis and do not apply to certain items such as medical supplies and donated food and water resource equipment intended to meet basic human needs. The foreign availability of items is supposed to be eliminated through negotiations with other countries.

- Preserve scarce natural resources: Another goal is to restrict the export of goods, wherever necessary, to protect the domestic economy from excessive drain on scarce resources (crude petroleum, certain inorganic chemicals) and to reduce the serious inflationary impact of foreign demand. Domestically produced crude oil and certain unprocessed timber harvested from federal and state lands are controlled because they are in short supply (EAR, part 754).

- Control proliferation: Export controls also aim to prevent the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, such as nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, which are often maintained as part of multilateral control arrangements (EAR, part 742.2).

The core of the export control provisions of the EAR concerns exports from the United States. However, the term “exports” has been given broad meaning to include activities other than exports and can apply to transactions outside the United States.

The scope of the EAR covers the following:

- Exports from the United States: This includes the release of technology to a foreign national in the United States through such means as demonstration or oral briefing (deemed export). The return of foreign equipment to its country of origin after repair in the United States, shipments from a U.S. foreign trade zone, and the electronic transmission of nonpublic data that will be received abroad also constitute U.S. exports.

- Re-exports by any party of commodities, software, or technology exported from the United States.

- Foreign products that are direct products of technology exported from the United States.

- Activities of U.S. persons: The EAR restricts the involvement of “U.S. persons,” that is, U.S. firms or individuals, in the exportation of foreign-origin items or in the provision of services that may contribute to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The regulations also restrict technical assistance by U.S. persons with respect to encryption commodities or software (EAR, part 732).

The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) is the primary licensing agency for dual-use exports. The term “dual use” distinguishes items (i.e., commercial items with military applications) covered by EAR from those covered by the regulations of certain other export licensing agencies, such as the Departments of State and Defense. Although “dual use” is often employed to refer to the entire scope of the EAR, the EAR also applies to some items that have solely civilian uses. It is also important to note that the export of certain goods is subject to the jurisdiction of other agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration (drugs and medical devices), the Department of State (defense articles), and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (nuclear materials).

Commerce Export License

Exports and other activities that are subject to the EAR are under the regulatory jurisdiction of the BIS. They may also be controlled under export-related programs of other agencies. Before proceeding to complete any export transaction, it is important to determine whether a license is required. The modalities of transportation are immaterial in the determination whether an export license is required, that is, an item can be sent by regular mail, hand carried on an airplane, or transmitted via e-mail or during a telephone conversation.

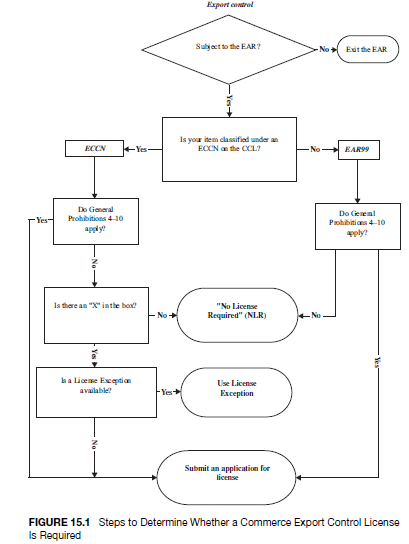

The following steps are important in establishing whether a given export item is subject to a license requirement (Figure 15.1).

Step 1: Is the item (intended for export) subject to EAR? Items subject to the EAR regulations include all items in the U.S. or abroad (including those in a U.S. free-trade zone), foreign- made items that are direct products of U.S.-origin technology or software (or that incorporate more than the stipulated minimum amounts of U.S.-origin materials), and certain activities of U.S. persons with regard to encryption commodities or software related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and technical assistance. It also covers activities of U.S. or foreign persons prohibited by any order (denied parties). Publicly available technology and software, phonograph records, magazines, and so on are excluded from the scope of EAR.

If the item is subject to the EAR, it is necessary to classify it under an ECCN (Export Control Classification Number) on the CCL (Commerce Control List). If it is not subject to EAR, there is no need to comply with the EAR. It may be necessary to comply with the regulations of another agency.

Step 2: Is the item classified under the ECCN on the CCL? Any item controlled by the Department of Commerce has an ECCN. Exporters should classify their product according to the Commerce Control List (CCL). They can also send an export classification request to the Department of Commerce. A request can also be made if an item has been incorrectly classified and/or should be transferred to another agency. Given certain changes that are made with regard to product classifications and the EAR, it is important to monitor the CCL for any modifications to your product, including eligibility for a license exception to certain destinations. Some companies may opt to use a computerized product/country license determination matrix. The CCL is composed of ten categories of items ranging from nuclear materials to propulsion systems, space vehicles and equipment. Each of these categories is further divided into five functional groups. Each controlled item has an export classification number (ECCN) based on its category and group.

Step 3: Do the general prohibitions (4-10) apply? Whether a product is listed under an ECCN on the CCL or not (EAR 99), it is important to determine whether general prohibitions on export/re-export to prohibited end uses, users, or embargoed destinations apply. The general prohibitions include engaging in activities prohibited by a denial order or supportive of proliferation activities as well as routing in-transit shipments through certain destinations. If an item is not listed under the ECCN on the commerce control list (EAR 99) and general prohibitions do not apply, no license is required. However, if the prohibitions apply (for items listed/not listed on ECCN), an application for a license should be submitted.

Step 4: Are there any controls on the country chart? The commerce country chart allows you to determine the export/re-export requirements for most items listed on the CCL. If an “X” appears in a particular cell, transactions subject to that particular reason for control (e.g., national security, antiterrorism)/destination combination require a license unless a license

exception applies. No license is required if the license exception is available provided that general prohibitions 4-10 do not apply to the proposed transaction. No license is required if there is no “X” indicated in the CCL and the country chart sample analysis using the CCL and country chart presented on page 331.

Step 5: Applying for an export license: The BIS provides formal classification for a product or service and issues an advisory opinion or a licensing decision upon review of a completed application submitted in writing or electronically. Even though it is the applicant’s responsibility to classify the export, the BIS could be requested to provide information on whether the item is subject to the EAR and, if so, its correct ECCN. In addition to the classification requests, potential applicants could also seek advisory opinions on whether a license is required or is likely to be granted for a particular transaction. Such opinions, however, do not bind the BIS’s future actions.

Step 6: Destination Control Statement, shipper’s export declaration, and record keeping: A Destination Control Statement (DCS) is intended to prevent items licensed for exports from being diverted while in transit or thereafter. A typical DCS reads as follows:

These commodities, technology or software were exported from the United States in accordance with the Export Administration Regulations for ultimate destination (name of country). Diversion contrary to U.S. law is prohibited.

A DCS must be entered on all documents covering exports from the United States of items on the CCL and is not required for items classified as EAR 99 (unless it is made under license exception BAG or GFT). DCS requirements do not often apply to re-exports. For holders of a Special Comprehensive License (SCL), use of a DCS does not preclude the consignee from re-exporting to any of the SCL holder’s other approved consignees or to other countries for which prior BIS approval has been received. An SCL allows experienced, high-volume exporters to export a broad range of items. It was introduced in lieu of special license and allows exportation of all commodities to all destinations (with some exceptions). Another DCS may be required on a case-by-case basis. The DCS must be shown on all copies of the bill of lading, the air waybill, and the commercial invoice (EAR, part 748). (See International Perspective 15.2 for automated services to facilitate export license applications).

Even though there are few exceptions, submission of a Shipper’s Export Declaration (SED) to the U.S. government is generally required under the EAR. Information on the SED, such as value of shipment, quantity, and so on, is also used by the Census Bureau for statistical purposes. The exporter or the authorized forwarding agent submits the SED, which includes information such as criterion under which the item is exported (i.e., license exception, no license required, license number and expiration date), ECCN, and other relevant information.

The exporter is required to keep records for every export transaction for a period of five years from the date of export. The records to be retained include contracts, invitation to bid, books of account, financial records, restrictive trade practices, and boycott documents or reports (EAR, part 762). (See Tables 15.2 and 15.3 for selected cases on export enforcement).

The following example provides an analysis using the CCL and country chart. In order to determine whether a license is required to export/re-export a particular item to a specific destination, it is essential to use the CCL in conjunction with the country chart (EAR, part 774).

This sample entry and related analysis are provided to demonstrate the thought process needed to complete this procedure.

Example: The item destined for export to India is valued at approximately $10,000 and classified under ECCN 2A000.a. On the basis of the item classification, we know that the entire entry is controlled for national security and antiterrorism reasons. The item appears in the country chart column, and the applicable restrictions are NS Column 2 and AT Column 1. An “X” appears in the NS Column 2 cell for India but not in the AT Column 1 cell. This means that a license is required unless it qualifies for a license exception or Special Comprehensive License. It may qualify under a license exception (GBS). (See International Perspective 15.3 for various multilateral arrangements on export controls).

Current Developments in Export Controls: In 2009, the U.S. government announced the launch of a comprehensive review of the U.S. export control system. The reform process is driven by the following important principles:

- Export controls should focus on a small core set of key items that pose a serious threat to U.S. national security (International Perspective 15.4 on U.S. export controls and China).

- Unilateral controls must address an existing legal or foreign policy objective.

- Export controls must be coordinated with other exporting nations in order to be effective.

- Export control lists must be revised on a regular basis (on the basis of technological developments, foreign availability). Licensing processes must be predictable and timely with enhanced enforcement capabilities to address noncompliance.

The Obama administration has proposed a number of changes to streamline the export control system:

- A single licensing agency: The present multiagency structure contributes to institutional squabbling among different agencies, and having one agency could end jurisdictional disputes. Under the present regime, dual-use exports are subject to referral to four departments.

- A single control list that distinguishes in tiers the sensitivity of items.

- A single enforcement structure: The center would coordinate export control enforcement efforts among various departments and serves as a liaison between law enforcement agencies as well as the intelligence community and export licensing agency.

- A single information technology system to share information among the relevant agencies (Fergusson and Kerr, 2012).

Sanctions and Violations

The enforcement of the EAR is the responsibility of the Bureau of Industry and Security, Office of Export Enforcement (located within the Department of Commerce). The Office of Export Enforcement (OEE) works with various government agencies to deter violations and imposes appropriate sanctions. Its major areas of responsibility include preventive enforcement, export enforcement, and prosecution of violators.

Preventive enforcement is intended to stop violations before they occur by conducting prelicense checks to determine diversion risks and the reliability of overseas recipients/end users of U.S. commodities/technology, as well as postshipment verifications. In 2011, BIS’s investigations resulted in the criminal convictions of thirty-nine individuals and businesses, with $20.2 million in penalties, $2.1 million in forfeitures, and 572 months of imprisonment. The BIS’s Office of Export Enforcement also conducts investigations of potential export control violations. When preventive measures fail, it pursues criminal and administrative sanctions. Violations of the EAR are subject to both criminal and administrative penalties. Fines for export violations can reach up to $1 million (U.S.) per violation in criminal cases, $12,000 per violation in most administrative cases, and $120,000 in cases involving national security issues. In addition, violators may be subject to prison time and denial of export privileges (i.e., they may be placed on the denied-persons list and/or face seizure/forfeiture

of goods). (See International Perspective 15.2, 15.5, and 15.6 for BIS automated services, control agencies, and general prohibitions.)

The EAR also provides certain indicators to help exporters recognize and report possible violations. It reminds exporters to look for the following in export transactions:

- Whether one of the parties to the transaction has a name or address that is similar to an entity on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s list of denied persons.

- Whether the transaction has “red flags.” Examples include (a) the customer or purchasing agent is reluctant to offer information about the end use of the product; (b) the customer is willing to pay cash for a very expensive item (when the terms provide for financing), has little or no business background, and is unfamiliar with the product, or the customer declines routine training installation or other services; (c) the product ordered is incompatible with the technical level of the country and its packaging is inconsistent with the stated method of shipment or destination; and (d) the shipping routes are abnormal for the producer and destination, delivery dates are vague, and a freight forwarding firm is listed as the product’s final destination.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

This really answered my downside, thanks!