Most producers do not sell their goods directly to the final users; between them stands a set of intermediaries performing a variety of functions. These intermediaries constitute a marketing channel (also called a trade channel or distribution channel). Formally, marketing channels are sets of interdependent organizations participating in the process of making a product or service available for use or consumption. They are the set of pathways a product or service follows after production, culminating in purchase and consumption by the final end user.2

Some intermediaries—such as wholesalers and retailers—buy, take title to, and resell the merchandise; they are called merchants. Others—brokers, manufacturers’ representatives, sales agents—search for customers and may negotiate on the producer’s behalf but do not take title to the goods; they are called agents. Still others— transportation companies, independent warehouses, banks, advertising agencies—assist in the distribution process but neither take title to goods nor negotiate purchases or sales; they are called facilitators.

Channels of all types play an important role in the success of a company and affect all other marketing decisions. Marketers should judge them in the context of the entire process by which their products are made, distributed, sold, and serviced. We consider all these issues in the following sections.

1. THE IMPORTANCE OF CHANNELS

A marketing channel system is the particular set of marketing channels a firm employs, and decisions about it are among the most critical ones management faces. In the United States, channel members as a group have historically earned margins that account for 30 percent to 50 percent of the ultimate selling price. In contrast, advertising typically has accounted for less than 5 percent to 7 percent of the final price.3 One of the chief roles of marketing channels is to convert potential buyers into profitable customers. Marketing channels must not just serve markets, they must also make them.4

The channels chosen affect all other marketing decisions. The company’s pricing depends on whether it uses online discounters or high-quality boutiques. Its sales force and advertising decisions depend on how much training and motivation dealers need. In addition, channel decisions include relatively long-term commitments with other firms as well as a set of policies and procedures. When an automaker signs up independent dealers to sell its automobiles, it cannot buy them out the next day and replace them with company-owned outlets. But at the same time, channel choices themselves depend on the company’s marketing strategy with respect to segmentation, targeting, and positioning. Holistic marketers ensure that marketing decisions in all these different areas are made to maximize value overall.

In managing its intermediaries, the firm must decide how much effort to devote to push and to pull marketing. A push strategy uses the manufacturer’s sales force, trade promotion money, or other means to induce intermediaries to carry, promote, and sell the product to end users. This strategy is particularly appropriate when there is low brand loyalty in a category, brand choice is made in the store, the product is an impulse item, and product benefits are well understood.

In a pull strategy the manufacturer uses advertising, promotion, and other forms of communication to persuade consumers to demand the product from intermediaries, thus inducing the intermediaries to order it. This strategy is particularly appropriate when there is high brand loyalty and high involvement in the category, when consumers are able to perceive differences between brands, and when they choose the brand before they go to the store.

Top marketing companies such as Apple, Coca-Cola, and Nike skillfully employ both push and pull strategies. A push strategy is more effective when accompanied by a well-designed and well-executed pull strategy that activates consumer demand. On the other hand, without at least some consumer interest, it can be very difficult to gain much channel acceptance and support, and vice versa for that matter.

2. MULTICHANNEL MARKETING

Today’s successful companies typically employ multichannel marketing, using two or more marketing channels to reach customer segments in one market area. HP uses its sales force to sell to large accounts, outbound telemarketing to sell to medium-sized accounts, direct mail with an inbound phone number to sell to small accounts, retailers to sell to still smaller accounts, and the Internet to sell specialty items. Each channel can target a different segment of buyers, or different need states for one buyer, to deliver the right products in the right places in the right way at the least cost.

When this doesn’t happen, channel conflict, excessive cost, or insufficient demand can result. Launched in 1976, Dial-a-Mattress successfully grew for three decades by selling mattresses directly over the phone and later online. A major expansion into 50 brick-and-mortar stores in major metro areas was a failure, however. Secondary locations, chosen because management considered prime locations too expensive, could not generate enough customer traffic. The company eventually declared bankruptcy.5

On the other hand, when a major catalog and Internet retailer invested significantly in brick-and-mortar stores, different results emerged. Customers near the store purchased through the catalog less frequently, but their online purchases were unchanged. As it turned out, customers who liked to spend time browsing were happy to either use a catalog or visit the store; those channels were interchangeable. Customers who shopped online, on the other hand, were more transaction-focused and interested in efficiency, so they were less affected by the introduction of stores. Returns and exchanges at the stores were found to increase because of ease and accessibility, but extra purchases made by customers returning or exchanging at the store offset any revenue deficit.6

Research has shown that multichannel customers can be more valuable to marketers.7 Nordstrom found that its multichannel customers spend four times as much as those who only shop through one channel, though some academic research suggests that this effect is stronger for hedonic products (apparel and cosmetics) than for functional products (office and garden supplies).8

3. INTEGRATING MULTICHANNEL MARKETING SYSTEMS

Most companies today have adopted multichannel marketing. Disney sells its videos through multiple channels: movie rental merchants such as Netflix and Redbox, Disney Stores (now owned and run by The Childrens Place), retail stores such as Best Buy, online retailers such as Disney’s own online stores and Amazon.com, and the Disney Club catalog and other catalog sellers. This variety affords Disney maximum market coverage and enables it to offer its videos at a number of price points.9 Here are some of the channel options for leather-goods maker Coach.10

COACH Coach markets a high-end line of luxury handbags, briefcases, luggage, and accessories. In its 2013 fiscal year 10-K, the company describes its multichannel global distribution model as follows: “Coach products are available in image-enhancing locations globally wherever our consumer chooses to shop including: retail stores and factory outlets, directly operated shop-in-shops, online, and department and specialty stores. This allows Coach to maintain a dynamic balance as results do not depend solely on the performance of a single channel or geographic area.” The North America segment consists of direct-to-consumer and indirect channels and includes sales to consumers through 351 company-operated retail stores, including the Internet, and sales to wholesale customers and distributors. Coach began as a U.S. wholesaler and still sells to 1,000 U.S. department-store locations, such as Macy’s (including Bloomingdale’s), Dillard’s, Nordstrom, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Lord & Taylor, often within a tightly controlled shop-within-a-shop, as well as on some of those retailer’s Web sites. This segment represented approximately 69 percent of the company’s total net sales in fiscal 2013. The International segment sells to consumers online and through company-operated stores in Japan and mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Korea and to wholesale customers and distributors. Coach also has store-in-store offerings in Japan and China inside major department stores. The International segment represented approximately 31 percent of total net sales in fiscal 2013. Finally, Coach has licensing relationships with Movado (watches), Jimlar (footwear), and Marchon (eyewear). These licensed products are sometimes sold in other channels such as jewelry stores, high-end shoe stores, and optical retailers as Coach continues to broaden its meaning from a “bag brand” to a whole lifestyle brand.

Companies are increasingly employing digital distribution strategies, selling directly online to customers or through e-merchants who have their own Web sites. In doing so, these companies are seeking to achieve omnichannel marketing, in which multiple channels work seamlessly together and match each target customer’s preferred ways of doing business, delivering the right product information and customer service regardless of whether customers are online, in the store, or on the phone.

An integrated marketing channel system is one in which the strategies and tactics of selling through one channel reflect the strategies and tactics of selling through one or more other channels. Adding more channels gives companies three important benefits. The first is increased market coverage. Not only are more customers able to shop for the company’s products in more places, as noted above, but those who buy in more than one channel are often more profitable than single-channel customers.11 The second benefit is lower channel cost—selling online or by catalog and phone is cheaper than using personal selling to reach small customers. The third is the ability to do more customized selling—such as by adding a technical sales force to sell complex equipment.

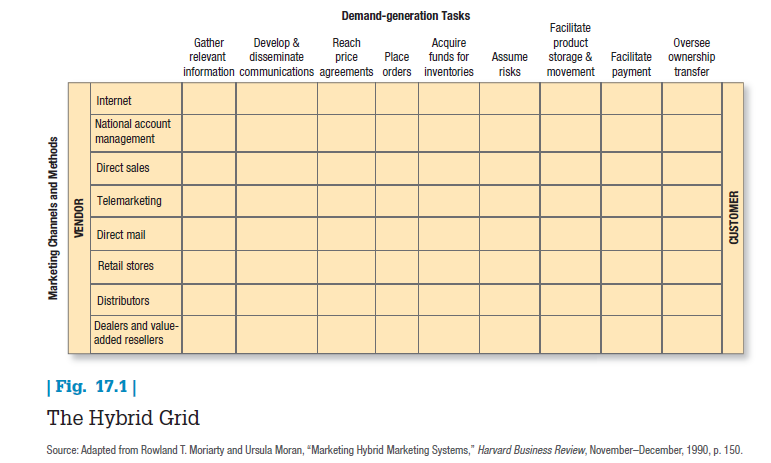

There is a trade-off, however. New channels typically introduce conflict and problems with control and cooperation. Two or more may end up competing for the same customers.12 Clearly, companies need to think through their channel architecture and determine which channels should perform which functions.13 Figure 17.1 shows a simple grid to help make channel architecture decisions. It consists of major marketing channels (as rows) and the major channel tasks to be completed (as columns).14

The grid illustrates why using only one channel is typically not efficient. Consider a direct sales force. A salesperson would have to find leads, qualify them, presell, close the sale, provide service, and manage account growth. With an integrated multichannel approach, however, the company’s marketing department could run a preselling campaign informing prospects about the company’s products through advertising, direct mail, and e-mails; generate leads through telemarketing, more e-mails, and trade shows; and qualify leads as hot, warm, or cool. The salesperson enters when the prospect is ready to talk business and invests his or her costly time primarily in closing the sale. This multichannel architecture optimizes coverage, customization, and control while minimizing cost and conflict.

Companies should use different sales channels for different-sized business customers—a direct sales force for large customers, a digital strategy or telemarketing for midsize customers, and distributors for small customers— but be alert for conflict over account ownership. For example, territory-based sales representatives may want credit for all sales in their territories, regardless of the marketing channel used.

Multichannel marketers also need to decide how much of their product to offer in each of the channels. Patagonia views the Web as the ideal channel for showing off its entire line of goods, given that its 88 retail locations are limited by space to offering a selection only, and even its catalog promotes less than 70 percent of its total merchandise.15 Other marketers prefer to limit their online offerings, theorizing that customers look to Web sites and catalogs for a “best of” array of merchandise and don’t want to have to click through dozens of pages. Here’s a company that has carefully managed its multiple channels.16

REI Outdoor equipment supplier REI has been lauded by industry analysts for the seamless integration of its retail store, Web site, Internet kiosks, mail-order catalogs, value-priced outlets, mobile app, and toll-free order number. If an item is out of stock in the store, all customers need to do is tap into the store’s Internet kiosk to order it from REI’s Web site. Less Internet-savvy customers can have clerks place the order for them at the checkout counters. And REI not only generates store-to-Internet traffic, it also sends online shoppers into its stores. If a customer browses REI’s site and stops to read an REI “Learn and Share” article on backpacking, the site might highlight an in-store promotion on hiking boots. To create a more common experience across channels, the specific icons and information used in ratings and reviews on REI.com also appear on in-store product displays. Like many retailers, REI has found that dual-channel shoppers spend significantly more than single-channel shoppers, and tri-channel shoppers spend even more. For example, one of every three people who buy something online will spend an additional $90 in the store when they come to pick that purchase up.

4. VALUE NETWORKS

A supply chain view of a firm sees markets as destination points and amounts to a linear view of the flow of ingredients and components through the production process to their ultimate sale to customers. The company should first think of the target market, however, and then design the supply chain backward from that point. This strategy has been called demand chain planning.17

A broader view sees a company at the center of a value network—a system of partnerships and alliances that a firm creates to source, augment, and deliver its offerings. A value network includes a firm’s suppliers and its suppliers’ suppliers and its immediate customers and their end customers. It also incorporates valued relationships with others such as university researchers and government approval agencies.

A company needs to orchestrate the work of these parties to deliver superior value to the target market. Oracle relies on 15 million developers—the largest developer community in the world.18 Apple Developer—where folks create iPhone apps for the Apple operating system—has 275,000 registered iOS members. Developers keep 70 percent of any revenue their products generate; Apple gets 30 percent. After releasing more than 850,000 apps that were downloaded 45 billion times in the first five years, Apple has paid out almost $9 billion.19

Demand chain planning yields several insights.20 First, the company can estimate whether more money is made upstream or downstream, in case it can integrate backward or forward. Second, the company is more aware of disturbances anywhere in the supply chain that might change costs, prices, or supplies. Third, companies can go online with their business partners to speed communications, transactions, and payments; reduce costs; and increase accuracy. Ford not only manages numerous supply chains but also sponsors many B-to-B Web sites and exchanges.

Managing a value network means making increasing investments in information technology (IT) and software. Firms have introduced supply chain management (SCM) software and invited such software firms as SAP and Oracle to design comprehensive enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems to manage cash flow, manufacturing, human resources, purchasing, and other major functions within a unified framework. They hope to break up departmental silos—in which each department acts only in its own self-interest—and carry out core business processes more seamlessly. Most, however, are still a long way from truly comprehensive ERP systems.

Marketers, for their part, have traditionally focused on the side of the value network that looks toward the customer, adopting customer relationship management (CRM) software and practices. In the future, they will increasingly participate in and influence their companies’ upstream activities and become network managers, not just product and customer managers.

5. THE DIGITAL CHANNELS REVOLUTION

The digital revolution is profoundly transforming distribution strategies. With customers—both individuals and businesses—becoming more comfortable buying online and the use of smart phones exploding, traditional brick- and-mortar channel strategies are being modified or even replaced.

Online retail sales (or e-commerce) have been growing at a double-digit rate; apparel and accessories, consumer electronics, and computer hardware are the three fastest-growing categories. Skeptics initially felt apparel wouldn’t sell well online, but easy returns, try-on tools, and customer reviews have helped counter the inability to try clothes on in the store.

As brick-and-mortar retailers promote their online ventures and other companies bypass retail activity by selling online, they all are embracing new practices and policies. As in all marketing, customers hold the key. Customers want the advantages both of digital—vast product selection, abundant product information, helpful customer reviews and tips—and of physical stores—highly personalized service, detailed physical examination of products, an overall event and experience. They expect seamless channel integration so they can:21

- Enjoy helpful customer support in a store, online, or on the phone

- Check online for product availability at local stores before making a trip

- Find out in-store whether a product that is unavailable can be purchased and shipped from another store to home

- Order a product online and pick it up at a convenient retail location

- Return a product purchased online to a nearby store of the retailer

- Receive discounts and promotional offers based on total online and offline purchases

Retailers and manufacturers are responding. Consider some of the changes being made by retail giant Walmart.22

WALMART With a huge investment in brick-and-mortar stores, many entrenched executives, and long- established policies, Walmart was slow to embrace online and mobile technology and had online operations accounting for less than 2 percent of its global sales. Then the company decided to make its digital strategy a priority, giving customers anytime, anywhere access to Walmart by combining mobile, online, and physical stores. After acquiring social-media start-up Kosmix, known for its strong expertise in search and analytics, it established its @WalmartLabs group in Silicon Valley, leading to company innovations such as smart-phone payment technology, mobile shopping applications, and Twitter-influenced product selection for stores. Walmart found that many of its core customer group who made $30,000 to $60,000 a year were shopping from its Web site in large numbers and often on smart phones rather than computers. Always a wizard with logistics, Walmart adopted a “ship from store” practice that uses its more than 4,000 U.S. stores as warehouses to fulfill online orders quickly. The company is also exploring same-day shipping. It improved the search engine on its Web site, increasing its “browsers to buyers” conversion by as much as 15 percent; launched its Shopycat gift recommendation app, which uses social media to suggest gifts; introduced its Scan and Go app so customers can automatically apply coupons when checking out; and added an in-aisle mobile-scanning system to speed check-out. A top priority for Walmart is its smart-phone app. Users of the app spend more and frequent the store twice as often as non-users. When near a store, the app flips into “store mode” to help locate items on a shopping list and make additional recommendations, provide a digital version of the latest circulars, and highlight new products available in the store.

Retailers and manufacturers are assembling massive amounts of social, mobile, and location (SoMoLo) information they can mine to learn about their customers. They are using software that closely monitors what’s selling where and at what price in order to adjust their offerings and prices.23 The goal for many marketers is to develop a customized “next best offer” (NBO) that takes into account customers’ attitudes and behavior, purchase (product or service), and shopping channel (in store or online) and the marketer’s goal with respect to those consumers, whether it is to increase sales, say, or build loyalty.24

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I have found It positively helpful and it has helped me out loads. I hope to contribute & assist other users like its aided me. Good job.