Dilthey is of central importance in the history of modem hermeneutics. He was not the first modern hermeneuticist, however. Around the turn of the nineteenth century and in the early years of that century, it was Friedrich Ast (1778-1841) and Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834) who extended hermeneutics beyond the realm of biblical exegesis. Schleiermacher, much more than Ast, strove to develop a general hermeneutics that would illuminate all human understanding and not just offer principles and mles for interpreting particular texts. He can be seen as the founder of modern hermeneutics.

1. SCHLEIERMACHER: GRAMMAR AND PSYCHOLOGY

Schleiermacher, a German Protestant theologian, was a professor at Halle from 1804 to 1807 and at Berlin from 1810.

For Schleiermacher, reading a text is very much like listening to someone speak. Speakers use words to express their thoughts and listeners are able to understand because they share the language that a speaker employs. They know the words, phrases and sentences that they are hearing and they understand the grammatical mles. On this basis, they are able to put themselves in the place of the speaker and recognise what the speaker is intending to convey. There is place, then, for a kind of empathy in the speaker-listener interchange and Schleiermacher extends this to the interpretation of texts.

Already we can see the twofold dimension that Schleiermacher posits in all hermeneutics. Hermeneutics is at once grammatical and psychological. Attention to the grammatical aspect situates the text within its literary context, at the same time reshaping that literary setting by the interpretation it makes of the text. On the more psychological side, the hermeneuticist is able to divine and elucidate not only the intentions of the author but even the author’s assumptions.

2. DLLTHEY’S ‘OBJECTIVE MIND

Schleiermacher’s biographer, Wilhelm Dilthey, is hailed as one of the most eminent philosophers of the late nineteenth century. For many years a professor at the University of Berlin, he continued his influential work after his retirement by gathering disciples around him in the final years of his life. What he emphasised to these followers was the twofold message he had preached throughout his teaching years: life and history, both inextricably intertwined.

From the positivists Dilthey had learned to eschew metaphysics, to regard all previous philosophy as partial only, and to base his own philosophy ‘on total, full experience, without truncations: therefore, on entire and complete reality’ (in Marias 1967, p. 379). In citing Dilthey to this effect, Marias tells us that, for Dilthey, philosophy ‘is the science of the real; that is, of all the real without truncations’ (1967, p. 383). For all that, Dilthey is no positivist, at least not in the sense in which positivism has come to be defined in our time. He believes firmly that human understanding can never exhaust the real and that in the real there will always remain something unknowable and ineffable. To be sure, we all have a Weltanschauung, a worldview that guides our actions; however this is grounded not in the intellect but in life.

The life Dilthey is referring to is, above all and before all, historical life. Dilthey is most aware of what he calls the rise of historical consciousness. He never loses sight of the historical character of the world and of ourselves within the world. Few have stressed the essentially historical character of human existence as forcefully as he does. The historicism12 we find today in so much of human and social science stems in no small measure from Dilthey. With the keenest of insights, he recognises what Marias calls ‘the peculiar ephemerality of the historical event’—that all people live within history and nothing, therefore, is definitive. History, Dilthey tells us, is ‘an immense field of ruins’ (in Marias 1967, p. 380). Gadamer, as we shall see, wants to reclaim the classical as ‘preservation amid the ruins of time’ (1989, p. 289). Dilthey will have none of that.

Dilthey’s emphasis on the historical character of life and the humanness of science (his interest is in the Geisteswissenschaften—the ‘sciences of the spirit’) leads him, as we have seen already, to distinguish sharply between natural reality and social phenomena. Unlike the phenomena encountered in nature, social phenomena are seen to stem from the subjectivity of human consciousness. Accordingly, Dilthey believes, study of the one and of the other calls for different methods. Even in the field of human and social science, however, he continues to seek objective knowledge. What he wants to elaborate is a methodology for gaining objective knowledge that escapes the reductionism and mechanism of natural science and remedies its failure to take account of the historical embeddedness of life.

For Dilthey, there are universal spiritual forms shaping the particular events one encounters in social experience. The texts humans write, the speech they utter, the art they create and the actions they perform are all expressions of meaning. Inquiring into that meaning is much more like interpreting a discourse or a poem than investigating a matter of natural reality through an experiment in, say, physics or chemistry. Scientific experiments seek to know and explain (Erkennen or Erklareri). Inquiry into human affairs seeks to understand (Verstehen). This distinction, as we have seen earlier, is often attributed to Weber. Whether that can jusdy be done at all is a moot point. If it is done, it calls at the very least for a number of important qualifications. We should also note Paul Ricoeur’s spirited attempt to supplant Dilthey’s dichotomy with a dialectical form of integration. Ricoeur (1976, p. 87) offers the notion of a ‘hermeneutical arc’ that moves from existential understanding to explanation and from explanation to existential understanding.

The early Dilthey invoked the notion of empathy as Schleiermacher had done. True enough, people’s perspectives, beliefs and values differ from age to age and culture to culture. Still, Dilthey felt at this time, we are all human beings and therefore able to understand—and, as it were, relive—what has happened in the past or in another place. This assumption on Dilthey’s part came under heavy fire at the time and he revised his views in the light of the criticism he was receiving. We find him adopting a far more historicist position, accepting that people’s speech, writings, art and behaviour are very much the product of their times. The historically derived worldview of authors constrains what they are able to produce and cannot be discounted in hermeneutical endeavours.

Dilthey comes to acknowledge, in fact, that the author’s historical and social context is the prime source of understanding. The human context is an objectification or externalisation—an ‘expression’ (Ausdruck), Dilthey also calls it—of human consciousness. He terms this the ‘objective mind’ and acknowledging it transforms his approach to hermeneutics. The psychological focus found in his work to date gives way to a much more sociological pursuit. Empathy is replaced by cultural analysis. Dilthey moves from personal identification with individuals to an examination of socially derived systems of meaning.

On the track of people’s ‘lived experience’ (Erlebnis) as fiercely as ever, he now accepts that their lived experience is incarnate in language, literature, behaviour, art, religion, law—in short, in their every cultural institution and structure.

Gaining hermeneutical understanding of these objectifications, extemalisations, or expressions of life involves a hermeneutic circle. The interpreter moves from the text to the historical and social circumstances of the author, attempting to reconstruct the world in which the text came to be and to situate the text within it—and back again.

In according a place in hermeneutics, as in all human understanding, to the interpreter’s lived experience, Dilthey has not abandoned his quest for an objective knowledge of the human world. True, the objectivity of this kind of knowledge will always differ from the scientific objectivity claimed, say, in the findings of physics and chemistry. Nevertheless, Dilthey believes, objectivity and validity can be increasingly achieved as more comes to be learned about the author and the author’s world, and as the interpreter’s own beliefs and values are given less play.

3. HEIDEGGER’S PHENOMENOLOGICAL HERMENEUTICS

The phenomenological hermeneutics of Martin Heidegger can, with even greater validity, be seen as a hermeneutical phenomenology. It is clearly the phenomenological dimension that is to the fore in his Being and Time (1962). For Heidegger, hermeneutics is the revelatory aspect of ‘phenomenological seeing’ whereby existential structures and then Being itself come into view.

Hermeneutics, Heidegger tells us, ‘was familiar to me from my theological studies’ (1971, pp. 10-11). Characteristically, Heidegger takes this word and gives it fresh meaning. In his hands it comes to represent the phenomenological project he has embarked upon.

… the meaning of phenomenological description as a method lies in interpretation. The Aoyos of the phenomenology of Dasein has the character of a £ppr]V£U£IV . . ,13 Philosophy is universal phenomenological ontology, and takes its departure from the hermeneutic of Dasein, which, as an analytic of existence has made fast the guiding- line for all philosophical inquiry at the point where it arises and to which it returns. (Heidegger 1962, pp. 61-2)

This passage reflects Heidegger’s lifetime focus on ontology, the study of being. For him, philosophy is ontology. Heidegger’s interest in ontology began as early as 1907 when he was given a doctoral dissertation to peruse. The dissertation, written by Franz Brentano, was entided Von der mannigfachen Bedeutung des Seienden nach Aristoteles (‘On the Manifold Meanings of Being in Aristode’). This volume caught the imagination of the eighteen-year-old Heidegger and launched him on a never-ending search for the meaning of being.

The passage just cited also reflects Heidegger’s adoption of phenomenology as the way into ontology. There is, as he sees it, no other way. If, for Heidegger, philosophy is ontology, ontology, by the same token, is phenomenology.

Phenomenology is our way of access to what is to be the theme of ontology, and it is our way of giving it demonstrative precision. Only as phenomenology is ontology possible. (Heidegger 1962, p. 60)

Let us recall what we have discussed already regarding phenomenology. It is an attempt to return to the primordial contents of consciousness, that is, to the objects that present themselves in our very experience of them prior to our making any sense of them at all. Sense has been made of them, of course. Our culture gives us a ready-made understanding of them. So we need to lay that understanding aside as best we can. Or, in Heidegger’s terms, we must rid ourselves of our tendency to immediately interpret.

The achieving of phenomenological access to the entities which we encounter, consists rather in thrusting aside our interpretative tendencies, which keep thrusting themselves upon us and running along with us, and which conceal not only the phenomenon of such ‘concern’, but even more those entities themselves as encountered of their own accord in our concern with them. (Heidegger 1962, p. 96)

Heidegger does not embark, therefore, on any exploration of culturally derived meanings. Indeed, he is most dismissive of these meanings as the seductive and dictatorial voice of das Man—the ‘they’, the anonymous One (Crotty 1997). What Heidegger embarks upon instead is a phenomenology of human being, or Dasein, to use the word that he consistendy uses.

Heidegger’s phenomenology of Dasein brings him, in the first instance, to his starting point on the journey towards Being, that is, the shadowy pre-understanding of Being that we all possess and which he calls the ‘forestructure’ of Being. Reaching that pre-understanding is already a phenomenology. Its further unfolding, together with the manifestation of Being itself and the unveiling of other phenomena in the light of Being, remains a phenomenological process throughout.

To talk of manifestation and unveiling is to talk in hermeneutical vein. And to talk of hermeneutics is to invoke the notions of interpretation and description. Heidegger is bringing together in a unitary way not only ontology and phenomenology but, through hermeneutics with its connotations of dialectics or rhetoric, the element of language as well. For Heidegger, Richardson tells us (1963, p. 631), hermeneutics and phenomenology become one: ‘If “hermeneutics” retains a nuance of its own, this is the connotation of language’.

For Heidegger, therefore, hermeneutics is not a body of principles or rules for interpreting texts, as it was for the earlier philologists. Nor is it a methodology for the human sciences, as Dilthey understood it to be. Heidegger’s hermeneutics refers ‘to his phenomenological explication of human existing itself (Palmer 1969, p. 42). Heidegger’s hermeneutics starts with a phenomenological return to our being, which presents itself to us initially in a nebulous and undeveloped fashion, and then seeks to unfold that pre-understanding, make explicit what is implicit, and grasp the meaning of Being itself.

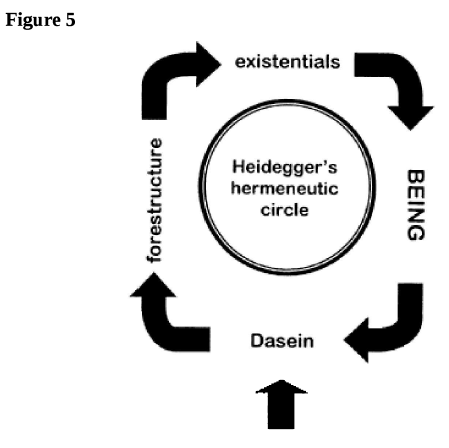

In a passage quoted above, Heidegger, in talking of the ‘hermeneutic of Dasein’, states that it makes fast the guiding-line for all philosophical inquiry ‘at the point where it arises and to which it returns’. Here Heidegger is describing his hermeneutical phenomenology as a circular movement. In our quest for Being, we begin with and from a preunderstanding of Being. The task is to unfold this rudimentary understanding and render explicit and thematic what is at first implicit and unthematised. This explication leads us first to a grasping of ‘existentials’—structures of being that make human existence and behaviour possible—and on to a grasping of Being itself. This more enlightened understanding of Being then returns to enrich our existence in the world.

What Heidegger is alluding to here is his version of the ‘hermeneutic circle’ (see Figure 5). We must, he tells us, ‘leap into the “circle”, primordially and wholly’ (1962, p. 363). As we have already seen, the term ‘hermeneutic circle’ has a long history, but Heidegger fills the term with meaning of his own. ‘This circle of understanding’, he tells us (1962, p. 195), ‘is not an orbit in which any random kind of knowledge may move; it is the expression of the existential forestructure of Dasein itself.

In his later works Heidegger is preoccupied with the second part of the circle. Instead of addressing Dasein as the entree to Being, he concerns himself direcdy with Being. The phenomenology of Dasein found in Being and Time is replaced by a hermeneutic dialogue with the pre-Socratic Greeks and with poets such as Holderlin.

There is, Heidegger believes, an originality about the thought of the early Greeks. They were in touch with Being in a way that has been subsequendy lost. We need, he tells us, to make ‘a painstaking effort to think through still more primally what was primally thought’ (1977, p. 303). In this shift in approach—the move from an analytic of Dasein to a running conversation with the early Greek thinkers—there is a new emphasis on history. Some commentators have accused Being and Time of being ahistorical. The same charge cannot be levelled at the later works. As the 1930s moved on, Heidegger focused more and more on the ‘history of Being’. He wrote of the ‘Event’ (Ereignis) wherein Being is unfolded within historical epochs, both giving itself to thought and withholding itself from thought.

From this perspective, the earliest Greek thought is a ‘selfblossoming emergence’ (Heidegger 1959, p. 14). It is primordial thought and its primal character needs to be recaptured. There at the dawn of Western civilisation it is a new beginning. As Heidegger puts it, ‘the beginning, conceived primally, is Being itself (Der Anfang—anfanglich begi’iffen—ist das Seyn selbst [1989, p. 58]). Hence his call to think through even more primally what is primally thought.

Heidegger also directs us to poetry, telling us that ‘our existence is fundamentally poetic’ (1949, p. 283). Poetry can lead us to the place where Being reveals itself. It provides the ‘clearing’ where Being is illuminated. Thoughtful poetising ‘is in truth the topology of Being’, a topology ‘which tells Being the whereabouts of its actual presence’ (Heidegger 1975, p. 12). The essence of poetry is ‘the establishing of being by means of the word’ (Heidegger 1949, p. 282) and the poet ‘reaches out with poetic thought into the foundation and the midst of Being’ (Heidegger 1949, p. 289).

In this conversation of the later Heidegger with the Greeks and the poets (and in Holderlin he finds a poet who is himself taken up with early Greek thought) is a new form of the hermeneutic circle. As Caputo underlines, it is a circling process between Being and beings. This is at once an unconcealing and a concealing. It is a ‘coming over’ of Being into beings and therefore a revelation of Being. Yet it is also the ‘arrival’ of beings and this means a concealing of Being. In this process, called by Heidegger the Austrag, ‘Being and beings are borne or carried outside of one another yet at the same time borne toward one another’ (Caputo 1982, p. 148).

Now aus-tragen is the literal translation of the Latin dif-ferre, dif-ferens, to carry away from, to bear outside of. Hence the Austrag is the differing in the difference between Being and beings, that which makes the difference between them, that which opens up the difference, holding them apart and sending them to each other in the appropriate manner, so that Being revealingly conceals itself in beings. (Caputo 1982, pp. 151-2)

As in Being and Time, here too hermeneutics means for Heidegger an unveiling of Being. It still means radical ontology. A profound change has occurred, however. Heidegger now sees the history of the West as the history of Being and is preoccupied with the Event that gives Being. All along he has charged Western thought with Seinsvergessenheit, ‘oblivion of Being’. Early on in his work, this was a reproach that we are preoccupied with beings to the neglect of Being. Now Heidegger changes tack. Western thought may be mindful enough of Being after its own fashion, but it has utterly ignored what opens up the difference between Being and beings. This is what Seinsvergessenheit means in the later Heidegger. He is telling us that the focus should lie with the Event rather than with the outcome of the Event. As Caputo explains (1982, pp. 2-4), we need ‘to think the sending and not to be taken in by what is sent, to think the giving and not to lose oneself in the gift’. In English we say ‘There is Being’, but the equivalent in German is ‘It gives (es gibt) Being’. Heidegger wants us to take a ‘step back’ and think the ‘It’ which Western metaphysics has traditionally left behind (Caputo 1982, p. 149).

According to the later Heidegger, then, ‘Being is “granted” to us in an experience that we must make every effort to render faithfully’ (Caputo 1982, p. 11). His own sustained attempt to render this experience faithfully constitutes the core of Heidegger’s hermeneutics.

4. GADAMER’S HISTORICAL HERMENEUTICS

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900- ) distances himself from both Schleiermacher and Dilthey and draws on his teacher, Heidegger, in his own fashion and for his own purposes.

Gadamer sees us as thoroughly historical—as, indeed, ‘historically effected’ consciousnesses. It is because of this historicality that we are able to link with the tradition of the past and interpret what has been handed on.

Gadamer thus argues initially that ‘hermeneutics must start from the position that a person seeking to understand something has a bond to the subject matter that comes into language through [tradition]’. (Rundell 1995, p. 32)

What Rundell is suggesting to us here is that there are two pivotal aspects of Gadamer’s thought. First, we stand in a tradition. Second, all tradition is wedded to language. Language is at the core of understanding, for ‘the essence of tradition is to exist in the medium of language’ and ‘the fusion of horizons that takes place in the understanding is actually the achievement of language’ (Gadamer 1989, pp. 378, 389).

For Gadamer, then, hermeneutical understanding is historical understanding. His is an historical hermeneutics that mediates past and present. It brings together the horizon of the past and the horizon of the present. As we have just seen, he describes this process as a fusion of horizons. This proves to be a key concept in his hermeneutics and he believes that an historical mediation of this kind between past and present underlies all historical activity as its ‘effective substratum’. ‘Understanding is to be thought of less as a subjective act than as participating in an event of tradition, a process of transmission in which past and present are constandy mediated’ (Gadamer 1989, p. 290).

In this fusion of horizons, the first pole is the past. Gadamer’s historical hermeneutics has to do with the past. ‘Hermeneutical experience is concerned with tradition’, says Gadamer (1989, p. 358). ‘This is what is to be experienced.’ He goes on to tell us (1989, p. 361) that the highest type of hermeneutical experience is ‘the openness to tradition characteristic of historically effected consciousness’.

The second pole is the present, the horizon of the interpreter. Not that we need consciously to bring the two poles together. They are ‘always already’ there. ‘Working out the historical horizon of a text’, Gadamer tells us (1989, p. 577), ‘is always already a fusion of horizons’. Thus, ‘the horizon of the present cannot be formed without the past. There is no more an isolated horizon of the present in itself than there are historical horizons which have to be acquired’ (Gadamer 1989, p. 306).

We need to look more closely at how Gadamer understands this ‘fusion of horizons’:

- The fusion of horizons shows ‘how historically effected consciousness operates’ and is, in fact, the ‘realization’ of ‘the historically experienced consciousness that, by renouncing the chimera of perfect enlightenment, is open to the experience of history’ (1989, pp. 341, 377-8).

- A fusion of horizons is required because the historical life of a tradition ‘depends on being constandy assimilated and interpreted’, so that every interpretation ‘has to adapt itself to the hermeneutical situation to which it belongs’ (1989, p. 397).

- The fusion of horizons is such that, ‘as the historical horizon is projected, it is simultaneously superseded’ (1989, p. 307).

- The fusion of horizons is the means whereby ‘we regain the concepts of a historical past in such a way that they also include our own comprehension of them’ (1989, p. 374).

- The fusion of horizons is such that ‘the interpreter’s own horizon is decisive, yet not as a personal standpoint that he maintains or enforces, but more as an opinion and a possibility that one brings into play and puts at risk, and that helps one truly to make one’s own what the text says’ (1989, p. 388).

- The fusion of horizons relates to ‘the unity of meaning’ in a work of art. The very point of historically effected consciousness is ‘to think the work and its effect as a unity of meaning’ (1989, p. 576). The fusion of horizons constitutes ‘the form in which this unity actualizes itself, which does not allow the interpreter to speak of an original meaning of the work without acknowledging that, in understanding it, the interpreter’s own meaning enters in as well’, (p. 576).

In this last citation, you will notice, Gadamer is referring to works of art. Artworks figure prominendy in his thought. They are for him the exemplar par excellence of what is handed down in tradition. Thus, Gadamer begins his major work Truth and Method with a treatise on aesthetics, which opens with a section on ‘the significance of the humanist tradition’ and concludes by linking aesthetics and history. We must acknowledge, he says ‘that the work of art possesses truth’. This is an acknowledgment that ‘places not only the phenomenon of art but also that of history in a new light’ (Gadamer 1989, pp. 41-2). Artworks ‘are contemporaneous with every age’ and ‘we have the task of interpreting the work of art in terms of time’ (Gadamer 1989, pp. 120-1).

Gadamer’s interest lies in historical works of art. We cannot really judge contemporary works, he feels, for any such judgment ‘is desperately uncertain for the scholarly consciousness’.

Obviously we approach such creations with unverifiable prejudices, presuppositions that have too great an influence over us for us to know about them; these can give contemporary creations an extra resonance that does not correspond to their true content and significance. Only when all their relations to the present time have faded away can their real nature appear, so that the understanding of what is said in them can claim to be authoritative and universal. (1989, p. 297)

Temporal distance thus performs a filtering function. It excludes ‘fresh sources of error’ and offers ‘new sources of understanding’ (Gadamer 1989, p. 298). Itself subject to ‘constant movement and extension’, the filtering process ‘not only lets local and limited prejudices die away, but allows those that bring about genuine understanding to emerge clearly as such’ (Gadamer 1989, p. 298).

The ‘prejudices’ that Gadamer is referring to are the inherited notions derived from one’s culture. Prejudices in this sense play a central role in Gadamer’s analysis. They are far more important in that analysis than any individual actions we might carry out. Not only is Gadamer not really interested in contemporary artworks, as we have just seen, but, for all his talk about our ‘judgment’ on works of art, he is not interested in individual judgments either. His concern lies with prejudices, and he strives mightily to redeem the notion of prejudice from the dismissiveness with which it is regularly greeted in current thought. He has already told us that understanding is not so much a subjective act as a placing of ourselves within a tradition. Now he warns us against the privatising of history. Our inherited prejudices stem from ‘the great realities of society and state’ and are immeasurably more important than the individual judgments recorded in self-awareness.

Self-reflection and autobiography—Dilthey’s starting points—are not primary and are therefore not an adequate basis for the hermeneutical problem, because through them history is made private once more. In fact history does not belong to us; we belong to it. Long before we understand ourselves through the process of self-examination, we understand ourselves in a self-evident way in the family, society, and state in which we live. The focus of subjectivity is a distorting mirror. The self- awareness of the individual is only a flickering in the closed circuits of historical life. That is why the prejudices of the individual, far more than his judgments, constitute the historical reality of his being. (Gadamer 1989, pp. 276-7)

A distorting mirror? Only a flickering in the closed circuits of historical life7. Gadamer offers litde comfort here to the many researchers who are eager to inquire into ‘private’ history. They focus quite intensely on ‘self-awareness’, ‘autobiography’, ‘self-examination and ‘self-reflection’ and, curiously, a number of them invoke Gadamer’s support in doing so. But he is obviously not on their side.

For Gadamer, the starting point is not the autonomous individual self so lionised in current versions of humanism. His starting point is the tradition in which we stand and which we are meant to serve. History does not belong to us. We belong to history! We find this stance confirmed as Gadamer looks for models for his historical hermeneutics.

He finds the models he is after in theological hermeneutics and legal hermeneutics. According to Gadamer, we are to consider the cultural tradition in the same light as the exegete considers the Scriptures and the jurist considers the law, that is, as a ‘given’. In the case of sacred texts and the law, the interpretative efforts of exegetes or jurists are obviously not to be seen in the light of ‘an appropriation as taking possession’ of the texts or a ‘form of domination’ of the texts. Like the exegete and the jurist, we too must see our hermeneutical endeavours as ‘subordinating ourselves to the text’s claim to dominate our minds’ and as a ‘service of what is considered valid’ (Gadamer 1989, p. 311).

Most forms of the tradition, ‘constandy assimilated and interpreted’ though they may be (Gadamer 1989, p. 397), still have to prove themselves worthy of such obeisance and service. They do so through the unity and coherence they display. For Gadamer, the cultural tradition is a universe of meaning. The meaningfulness of transmitted texts is determined by the tradition as a whole, just as the tradition as a whole is a unity comprising the meaning of the texts transmitted within it. Gadamer insists that we read the tradition in this way:

Thus the movement of understanding is constandy from the whole to the part and back to the whole. Our task is to expand the unity of the understood meaning centrifugally. The harmony of all the details with the whole is the criterion of correct understanding. The failure to achieve this harmony means that understanding has failed. (1989, p. 291)

This is Gadamer’s great hermeneutic rule. We are to extend the unity of understanding in ever-widening circles by moving from whole to part and from part to whole. Brenkman, for one (1987, pp. 26-44), finds this principle problematic. Gadamer imposes it as a methodological tool (it is our ‘task’); yet he wants to claim that our experience of the tradition as an organic unity is premethodological. Is Gadamer wanting to have it both ways, then? Brenkman’s criticism is not without foundation. Is the unity, which Gadamer values so highly, inherent in the tradition, as he claims? Or is it imparted to the tradition by the way in which he insists that we read it?

Moreover, there are forms of the tradition that escape the need even for this kind of validation. These are ‘classical’ forms. The classical, Gadamer tells us, ‘epitomizes a general characteristic of historical being: preservation amid the ruins of time’ (1989, p. 289). In confronting other forms of the tradition, we need to overcome the barrier of distance. Not so with the classical. ‘What we call “classical” Gadamer tells us, ‘does not first require the overcoming of historical distance, for in its own constant mediation it overcomes this distance by itself (1989, p. 290).

The ‘classical’ is something raised above the vicissitudes of changing times and changing tastes. It is immediately accessible . . . when we call something classical, there is a consciousness of something enduring, of significance that cannot be lost and that is independent of all the circumstances of time—a kind of timeless present that is contemporaneous with every other present. (Gadamer, 1989, p. 288)

What is one to make of this? Gadamer uses religious and legal hermeneutics as models and calls on hermeneuticists to ‘serve the validity of meaning’. This validity is taken, without further ado, to be found in all classical works. It is also found in any other forms of the tradition that pass Gadamer’s unity-and-coherence test. As Brenkman points out, this approach ignores the social site of the work’s genesis and the social site of its reception and takes no account of the hegemony and oppression inherent in both of them. This is an essentially conservative position and has drawn the fire of more critically minded analysts. Jurgen Habermas, for example, finds Gadamer’s embrace of tradition particularly problematic and he has engaged in debate with him over many years on this and other issues.

This dialogue has led Habermas to a ‘critical hermeneutics’. Joined by Apel and others, Habermas is insistent that no hermeneutics can prescind from the setting in which understanding occurs. At once social, historical and discursive, this setting is the batdeground of many interests and no analyst or researcher can afford to ignore it, as the discussion in the next two chapters will highlight.

5. Hermeneutics, reading theory and literary criticism

Hermeneutics is invoked in many fields of inquiry relating to the act of reading. These include literary criticism and reading comprehension theory. As Stanley Straw asserts, ‘hermeneutics … is an activity related to all criticism in its attempt to make meaning out of the act of reading’ (1990b, p. 75). Not everybody agrees. Hirsch, for example, makes a sharp distinction between hermeneutics and literary criticism based on a ‘rigid separation of meaning and significance’ (1967, p. 142).

Even among those who accord hermeneutics a rightful place in reading theory and literary criticism, there have been, and are, many conflicting viewpoints. In the main, these have to do with the respective place and status to be accorded in interpretation to author, text and reader. One might, in fact, conceive of interpretation theory as a continuum that privileges author or text at one end and reader at the other.

If we do conceive interpretation theory as a continuum of that kind, at what point on the spectrum would we place someone like novelist and critic Umberto Eco? While it would be difficult to position him with any kind of precision, he would have to be seen as standing at some distance from either extreme. On any accounting, he would not be up at the end that privileges the reader. For several decades now, Eco believes, the role ascribed to the reader in the task of interpretation has been exaggerated. In reaction to this, he draws attention (1992, pp. 64-6) to the importance of the intentio operis (literally, the ‘intention of the work’, that is, the purpose expressed in and by the text itself) over against the intentio lectoris (the ‘intention of the reader’, that is, the personal purpose that the reader brings to the reading or infuses into the reading). This reflects a time-honoured Scholastic distinction between intentio operis and intentio operands. The former is a purpose intrinsic to the action being done, while the latter is a purpose brought to the action by the agent. In the context of hermeneutics, Eco uses this distinction to resist the prevailing trend to privilege the reader. Overemphasising the reader’s role leads to what he dubs ‘overinterpretation’. It opens the floodgates to an undifferentiated torrent of interpretations. Eco refers (1992, p. 34) to ‘the idea of the continuous slippage of meaning’ found in many postmodernist concepts of criticism.

Not that Eco is overlooking the extent to which textual meanings can be indeterminate. Nor is he denying the reader a genuinely critical role in interpretation. His approach allows for many diverse interpretations to emerge. Yet he does want to set some limits. A message, Eco says (1992, p. 43), ‘can mean many things but there are senses it would be preposterous to accept’.

What Eco is attempting to establish is a ‘dialectical link’ between intentio operis and intentio lectoris. The reader, he feels, ought to have some ideas regarding the purpose of the work in question. The text, surely, is about something. Glimpsing this ‘aboutness’ provides readers with a sense of direction. How will readers know whether their assumptions about the intentio operis are justified? Rather like the ancient Greeks referred to earlier, and like Gadamer with his hermeneutic rule, Eco believes that texts have a certain unity and coherence. One may have confidence in one’s ‘sense of aboutness’ if it holds up throughout the entire work. If it does not hold up, one needs to think again. Thus, ‘the internal textual coherence controls the otherwise uncontrollable drives of the reader’ (Eco 1992, p. 65).

Eco’s standpoint has many critics. Some find him too liberal. Others find him too restricting.

First of all, there are those who welcome Eco’s emphasis on purposes but feel he does not go far enough. It is not enough, they suggest, to invoke intentio operis. Intentio auctoris—authorial intent—must be identified and taken into account. The attitude of such critics tends to be straightforward, if nothing else. ‘A text means what its author intended it to mean’, write Knapp and Michaels (1985, p. 469). This, of course, is a very traditional approach to reading.

There are others, however, for whom Eco’s viewpoint is far too restrictive. For a start, they question his assumption that all texts have sufficient unity and coherence to ground the intention he looks to establish. Moreover, they fear, to limit authentic interpretation to what is considered intentio operis or intentio auctoris means in practice to subject the interpreter to ‘canonical’ or ‘classical’ readings of the text and preclude other ways of interpreting it. This, in their view, is impoverishing.

One thinks, for instance, of feminist author Adrienne Rich’s celebrated call to ‘re-vision’ texts (1990, pp. 483-4). She defines revision as ‘the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction’. Re-vision means a radical feminist critique of literature, which will use literature as a clue to how women have been living and how women can ‘begin to see and name— and therefore live—afresh’. ‘We need’, says Rich, ‘to know the writing of the past, and know it differendy than we have ever known it; not to pass on a tradition but to break its hold on us’. In a feminist hermeneutic of this kind, for all its lack of focus on authorial or textual intent, there is surely both authenticity of interpretation and richness of meaning. Who would deny that?

These viewpoints—seeing interpretation as essentially an identification of authorial intent, or looking instead to an intention intrinsic to the text as such, or making the reader pivotal in the generation of meaning—are embodied, with their many variants, in the history of both literary criticism and reading comprehension theory. Tracing ‘the history of conceptualizations of reading’, Straw and Sadowy (1990, p. 22) point to a movement ‘from a transmission notion of reading (roughly, from 1800 to 1890), to a translation notion of reading (roughly, 1890 to the late 1970s), to an interactive notion of reading (a notion predominant now within the reading establishment)’. The authors detect a further movement over the past few years to ‘transactional and constructionist notions of reading’ (1990, p. 22).

Straw uses the same terms, and identifies the same phases, to characterise changes that have occurred historically within literary theory in North America. In the ‘transmission’ period, the emphasis was on the author’s intentions. ‘Positivist/expressive realism notions of literary theory and criticism held English studies in a choke-hold well into the twentieth century’, writes Straw (1990a, p. 53); ‘reading the text was the same as reading the author’. The ‘transmission’ period was followed by a ‘translation’ period after World War I. Formalist approaches to texts emerged—in the shape of Russian Formalism in continental Europe and New Criticism in Anglo-American circles. This move replaced nineteenth-century deification of the author with a twentieth-century reification of the text. The New Critics ‘insisted on the presence within the work of everything necessary for its analysis; and they called for an end to any concern by critics and teachers of English with matters outside the work itself—the life of the author, the history of his times, or the social and economic implications of the literary work’ (Guerin et al. 1979, p. 75).

The ‘translation’ phase did not last. In Europe, first of all, and then in the Anglo-American world, it gave way to an ‘interaction’ period. A systems approach began to be applied to literature, as elsewhere, and this ‘culminated in what has been called “Structuralism in Literature’” (Straw 1990a, p. 58). Structuralist thought, growing out of the linguistic principles of Saussure, came to be applied to many diverse fields. In literary criticism it led to a proliferation of highly nuanced approaches that, for all their diversity, share a belief ‘that structures can be used systematically to reach an interpretation of any particular text’ (Straw 1990a, p. 61).

What they also share (and even share with their allegedly antistructuralist opponents) is an understanding that literary criticism is interactionist in nature. In the earlier phases, to be sure, interpretation had been seen as a matter of communication. This remains the case in the interactive phase, even if it is now seen as essentially intercommunication—not one-way transmission of a message from author to reader but interplay between author and reader via the text.

Important as it is, the understanding of reading and criticism as interaction does not signal an end to development, or even a slowing of development. Thinking in relation to interpretation of texts has already moved on from its interactive phase. It has moved ‘beyond communication’, Straw tells us. What has emerged is a transactional understanding of reading and interpretation.

In contrast to conceptualizations of reading built on the communication model, transactional models suggest that reading is a more generative act than the receipt or processing of information or communication. From the transactional view, meaning is not a representation of the intent of the author; it is not present in the text; rather, it is constructed by the reader during the act of reading. The reader draws on a number of knowledge sources in order to create or construct meaning. (Straw 1990b, p. 68)

This, we will note, relates closely to our earlier considerations under the rubric of constructivism. Straw goes on to say of texts what others, like Merleau-Ponty, have said of the world and objects in the world, namely, that their meaning is indeterminate. Given such indeterminacy, ‘transactional theories suggest that meaning is created by the active negotiation between readers and the text they are reading’. What is happening is a ‘generating of meaning in response to text’. Recognition of this transactional dimension is found in reception theorists in Germany, post-structuralists in France, and reader-response critics in the Anglophone countries (Straw 1990b, p. 73).

While different periods emphasise particular ways of understanding the act of reading or analysing the process of textual criticism and tend to portray each of them in exclusivist fashion, perhaps we should just acknowledge that there are different ways of reading and interpreting. Each way has something to offer researchers as they gather their data and especially as they interpret the data they have gathered. Approaches that privilege author, or text, or reader, need not be seen as either watertight compartments or incompatible options.

Some scholars, as we have seen, inveigh against giving weight to authorial intent or to textual form and content. They do so on the ground that this inhibits the freedom of the interpreter. They want to see the interpreter left free to engage uninhibitedly with the text and able to construct meaning without restraint. Yet, if we are talking about freedom, it is surely a gross limitation on interpreters to regard as null and void any readings that look to the author’s personality, or the author’s life and times, or the author’s stated or implied intentions. It is equally a gross limitation on interpreters to dismiss interpretations that draw direcdy on features of the text as such. Interpreters would seem to be most free when they are left at liberty to read and interpret in a wide variety of ways.

A first way to approach texts might be described as empathic. This is an approach characterised by openness and receptivity. Here we do more than extract useful information from our reading. The author is speaking to us and we are listening. We try to enter into the mind and personage of the author, seeking to see things from the author’s perspective. We attempt to understand the author’s standpoint. It may not be our standpoint; yet we are curious to know how the author arrived at it and what forms its basis.

There can also be an interactive approach to texts. Now we are not just listening to the author. We are conversing. We have a kind of running conversation with the author in which our responses engage with what the author has to say. Dialogue of this kind can have a most formative and growthful impact on ideas we brought to the interchange. Here, in fact, our reading can become quite critical. It can be reading ‘against the grain’.

Then there is the transactional mode of reading. What happens in this mode is much more than refinement, enhancement or enlargement of what we bring to our engagement with the text. Out of the engagement comes something quite new. The insights that emerge were never in the mind of the author. They are not in the author’s text. They were not with us as we picked up the text to read it. They have come into being in and out of our engagement with it.

These are all possible ways of reading. There are others beside. And we are free to engage in any or all of them. These various modes prove suggestive and evocative as we recognise research data as text—and, even before that, as we take human situations and interactions as text. In this hermeneutical setting, ways of reading are transfigured as ways of researching.

Hermeneutics as it appears in reading theory and literary criticism seems much more run of the mill than the hermeneutics we encounter in Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger, Gadamer and Ricoeur. In reading theory and literary criticism, it seems litde more than a synonym for interpretation. Nor does hermeneutics seem much more than a synonym for interpretation in many contemporary instances where the term is invoked to describe the research process engaged in.

In the more philosophical and especially the more historical usage of the term, there is a certain mystique to be reckoned with. Whether we are speaking of Dilthey’s universal spiritual forms that shape social events within human history, or of Heidegger’s search for the Event that gives Being, or of Gadamer’s fusion of horizons between past and present, there seems to be a grandeur and profundity, a certain aura, about what is going on. Hermeneutics in this vein, it would seem, is not just any old attempt at interpretation.

It would not be right to put too firm a wedge between these two forms. After all, literary critics are not at all averse to citing Heidegger and Gadamer. Nevertheless, the mystique just referred to is hardly mirrored in social research that employs, say, observation and interviewing and analyses its data by allowing major themes to emerge in quite straightforward ways. Historical research that looks to interpret tradition, the classics, and the canon of literature and art we have inherited (or, indeed, historical research that looks to break with the traditional, the classical and the canonical) would seem to square much better with the hermeneutics stretching from Schleiermacher to Ricoeur.

Horses for courses, then. Researchers looking to get a handle on people’s perceptions, attitudes and feelings—or wanting to call these into question as endemic to a hegemonic society and inherited from a culture shaped by class, racial and sexual dominance—may be best placed to find useful insights if they look to the hermeneutics of the reading theorists and the literary critics. On the other hand, in research that echoes with profoundly spiritual, religious, historical or ontological overtones, especially where we are linked to other interpretative communities in ways that both bring us close and place us at a distance, it may be profitable to seek guidance in the philosophico-historical rendering of hermeneutics.

Either way, our debt to the hermeneutic tradition is large.

Source: Michael J Crotty (1998), The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process, SAGE Publications Ltd; First edition.

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021