The European Union (EU) is the oldest and most significant economic integration scheme, involving twenty-eight Western and Eastern European countries: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. One of the most important developments is the recent EU enlargement from fifteen to twenty- five countries in May 2004 with the admission of Cyprus, Malta, and eight East European countries. In January 2007, Bulgaria and Romania became EU members and in July, 2013, Croatia joined the EU, increasing the number of members to twenty-eight countries. Turkey and other East European countries will be considered for admission in the coming years on the basis of certain criteria such as having stable democratic institutions, a free market, and the ability to assume EU treaty obligations (Poole, 2003; Van Oudenaren, 2002).

Even though the European economic integration dates back to the Treaty of Rome in 1957, the European Union is the outcome of the Maastricht treaty of 1992. The European Union has an aggregate population of about 503 million people and a total economic output (GDP) of $16 trillion (U.S.) (2012), and the agreement involves the largest transfer of national sovereignty to a common institution (International Perspective 2.3). In certain designated areas, for example, international agreements can be made only by the European Union on behalf of member states (Wild, Wild, and Han, 2006).

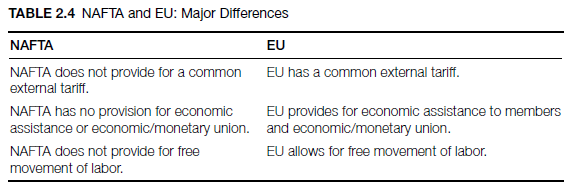

The pursuit of such integration was party influenced by the need to create a lasting peace in Europe as well as to establish a stronger Europe that could compete economically against the United States and Japan (Table 2.4). Since the countries were not large enough to compete in global markets, they had to unite in order to exploit economies of large-scale production.

The objectives of European integration as stated in the Treaty of Rome (1957) are as follows:

- To create free trade among member states and to provide uniform customs duties for goods imported from outside the EU (common external tariff).

- To abolish restrictions on the free movement of all factors of production, that is, labor, services, and capital. Member states are required to extend the national treatment standard to goods, services, capital, and so on from other member countries with respect to taxation, and other matters (nondiscrimination).

- To establish a common transport, agricultural, and competition policy.

A number of the objectives set out in the Treaty of Rome were successfully accomplished. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) was established in 1962 to maintain common prices for agricultural products throughout the community and to stabilize farm incomes. Tariffs between member nations were eliminated and a common external tariff established in 1968. However, efforts to achieve the other objectives, such as a single internal market (elimination of nontariff barriers), free movement of services and capital, and so forth was slow and difficult. Coordinated or common policies in certain areas such as transport simply did not exist (Archer and Butler, 1992).

The European Commission presented a proposal in 1985 to remove existing barriers to the establishment of a genuine common market. The proposal, which was adopted and entitled The Single European Act (SEA), constitutes a major revision to the Treaty of Rome. The Single European Act set the following objectives for its members:

- To complete the single market by removing all the remaining barriers to trade such as customs controls at borders, harmonization of technical standards, liberalization of public procurement, provision of services, removal of obstacles to the free movement of workers, and so on. In short, efforts involved the removal of physical, technical, and fiscal (different excise and value added taxes) barriers to trade.

- To encourage monetary cooperation leading to a single European currency. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 further reinforced this and defined plans for achieving economic and monetary union.

- To establish cooperation on research and development (R&D) and to create a common standard on environmental policy.

- To harmonize working conditions across the community and to improve the dialogue between management and labor.

The Single European Act established a concrete plan and timetable to complete the internal market by 1992. It is fair to state that most of the objectives set out under the SEA were accomplished: border checks are largely eliminated, free movement of workers has been achieved through mutual recognition of qualifications from any accredited institution within the EU, free movement of capital (banks, insurance and investment services) has been made possible with certain limitations, and the single currency (the euro) was introduced in 1999. The euro has helped reduce transaction costs by eliminating the need to convert currencies and made prices between markets more transparent. There still exist a number of challenges in completing and sustaining the single market, expanding EU policy responsibilities in certain controversial areas such as energy policy, and undertaking appropriate structural reforms to take advantage of the economic and monetary union.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

Very interesting info !Perfect just what I was searching for!