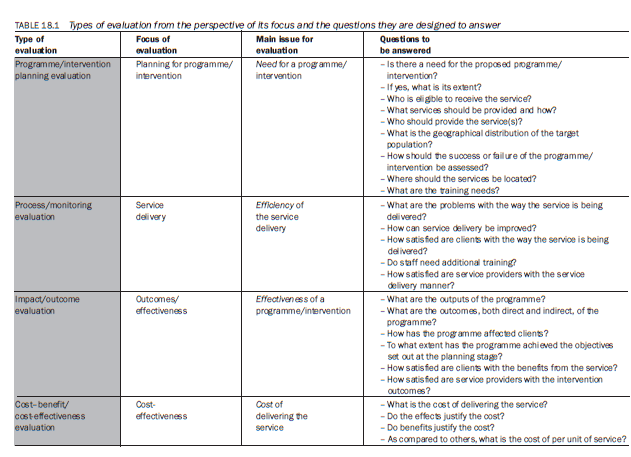

From the perspective of the focus of evaluation there are four types of evaluation: programme/ intervention planning, process/monitoring, impact/outcome and cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness. Each type addresses a main and significantly different issue. Evaluation for planning addresses the issue of establishing the need for a programme or intervention; process evaluation emphasises the evaluation of the process in order to enhance the efficiency of the delivery system; the measurement of outcomes is the focus of an outcome evaluation; and the central aim of a cost-benefit evaluation is to put a price tag on an intervention in relation to its benefits. Hence, from this perspective, the classification of an evaluation is primarily dependent upon its focus.

It is important for you to understand the different evaluation questions that each is designed to answer. Table 18.1 will help you to understand the application of each type of evaluation.

1. Evaluation for programme/intervention planning

In many situations it is desirable to examine the feasibility of starting a programme/ intervention by evaluating the nature and extent of a chosen problem. Actually, this type of study evaluates the problem per se: its nature, extent and distribution. Specifically, programme planning evaluation includes:

- estimating the extent of the problem – in other words, estimating how many people are likely to need the intervention;

- delineating the characteristics of the people and groups who are likely to require the intervention;

- identifying the likely benefits to be derived from the intervention;

- developing a method of delivering the intervention;

- developing programme contents: services, activities and procedures;

- identifying training needs for service delivery and developing training material;

- estimating the financial requirements of the intervention;

- developing evaluation indicators for the success or failure of the intervention and fixing a timeline for evaluation.

There are a number of methods for evaluating the extent and nature of a problem, and for devising a service delivery manner. The choice of a particular method should depend upon the financial resources available, the time at your disposal and the level of accuracy required in your estimates. Some of the methods are:

- Community need-assessment surveys – Need-assessment surveys are quite prevalent to determine the extent of a problem. You use your research skills to undertake a survey in the relevant community to ascertain the number of people who will require a particular service. The number of people requiring a particular service can be extrapolated using demographic information about the community and results from your community sample survey. If done properly, a need-assessment survey can give you a reasonably accurate estimate of the needs of a community or the need for a particular type of service. However, you must keep in mind that surveys are not cheap to undertake.

- Community forums – Conducting community discussion forums is another method used to find out the extent of the need for a particular service. However, it is important to keep in mind that community forums suffer from a problem in that participants are self-selected; hence, the picture provided may not be accurate. In a community forum not everyone will participate and those who do may have a vested interest for or against the service. If, somehow, you can make sure that all interest groups are represented in a community forum, it can provide an reasonable picture of the demand for a service. Community forums are comparatively cheap to undertake but you need to examine the usefulness of the information for your purpose. With community forums you cannot ascertain the number of people who may need a particular service, but you can get some indication of the demand for a service and different prevalent community perspectives with respect to the service.

- Social indicators – Making use of social indicators, in conjunction with other demographic data, if you have information about them, is another method. However, you have to be careful that these indicators have a high correlation with the problem/need and are accurately recorded. Otherwise, the accuracy of the estimates will be affected.

- Service records – There are times when you may be able to use existing service records to identify the unmet needs for a service. For example, if an agency is keeping a record of the cases where it has not been able to provide a service for lack of resources, you may be able to use it to estimate the number of people who are likely to need that service.

- Focus groups of potential service consumers, service providers and experts – You can also use focus groups made up of consumers, service providers and experts to establish the need for a service.

Community surveys and social indicators tend to be quantitative, whereas the others tend to be qualitative. Thus they give you different types of information. Service records provide an indication of the gap in service and are not reflective of its need.

It is important to remember that all these methods, except the community needs survey, provide only an indication of the demand for a service in a community.You have to determine how accurately you need to estimate the potential number of users to start a service. A community survey will provide you with the most accurate figures but it could put a strain on the resources. Also, keep in mind that use of multiple methods will produce more accurate estimates.

2. Process/monitoring evaluation

Process evaluation, also known as monitoring evaluation, focuses on the manner of delivery of a service in order to identify issues and problems concerning delivery. It also identifies ways of improving service delivery procedures for a better and more efficient service. Specifically, process evaluation is used for:

- determining whether or not the delivery of a service is consistent with the original design specifications and, if not, for identifying the reasons and justifications for non-compliance;

- identifying changes needed in the delivery manner for greater coverage and efficiency;

- ascertaining, when an intervention has no impact, whether this is because of the intervention itself or the manner in which it is being delivered;

- determining whether or not an intervention is reaching the appropriate target population.

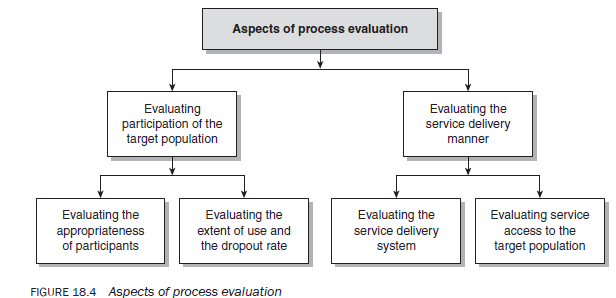

Process evaluation includes evaluating the:

- extent of participation of the target population;

- delivery manner of a programme/intervention.

Evaluating the participation of the target population in turn involves: (1) ascertaining the appropriateness of the clients for the service in question; and (2) establishing the total number of clients and the dropout rate among them. Evaluating the service delivery manner, in the same way, includes two tasks: (1) examining the procedures used in providing the service; and (2) examining the issues relating to the accessibility of the service to potential clients (Figure 18.4).

3. Evaluating participation of the target population

In an evaluation study designed to examine the process of delivering an intervention, it is important to examine the appropriateness of the users of the service because, sometimes, some people use a service even though they do not strictly fall within the inclusion criteria. In other words, in evaluation studies it is important to determine not just the number of users, but whether or not they are eligible users. Determining the appropriate use of an intervention is an integral part of an evaluation.

It is also important to ascertain the total number of users of a programme/intervention because it provides an indication of the need for a service, and to find out the number of dropouts because this establishes the extent of the rejection of the service for any reason. There are a number of procedures for evaluating the participation of a target population in an intervention:

- Percentage of users – The acceptance of a programme by the target population is one of the important indicators of a need for it: the higher the acceptance, the greater the need for the intervention. Some judge the desirability of a programme by the number of users alone. Hence, as an evaluator, you can examine the total number of users and, if possible, calculate this as a percentage of the total target population. However, you should be careful using the percentage of users in isolation as an indicator of the popularity of a programme. People may be unhappy and dissatisfied with a service, yet use it simply because there is no other option available to them. If used with other indicators, such as consumer satisfaction or in relation to evidence of the effectiveness of a programme, it can provide a better indication of its acceptance.

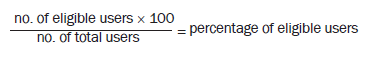

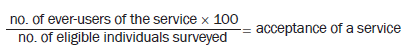

- Percentage of eligible users of a service – Service records usually contain information on service users that may include data on their eligibility for the service. An analysis of this information will provide you with a percentage of eligible users of the service: the higher the percentage of eligible users, the more positive the evaluation. That is,

You can also undertake a survey of the consumers of a service in order to ascertain the percentage of eligible users.

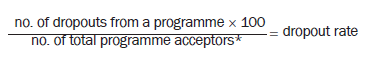

- Percentage of dropouts – The dropout rate from a service is reflective of the satisfaction level of consumers with the programme. A higher rate indicates either inappropriate service content or flaws in the way the service is being delivered: it does not establish whether the problem is with the delivery manner or the intervention content. However, the figure will provide you with an overall indication of the level of satisfaction of consumers with the service: the higher the dropout rate, the higher the level of dissatisfaction, either with the contents of a service (its relevance to the needs of the population) or the way it is being delivered.

*Acceptors are ever-users of a service.

- Survey of the consumers of a service – if service records do not include data regarding client eligibility for a service, you can undertake a survey of ever-users/acceptors of the service to ascertain their eligibility for the service. From the ever-users surveyed, you can also determine the dropout rate among them. In addition, you can find out many other aspects of the evaluation, such as client satisfaction, problems and issues with the service, or how to improve its efficiency and effectiveness. How well you do this survey is dependent upon your knowledge of research methodology and availability of resources.

- Survey of the target population – Target population surveys, in addition to providing information about the extent of appropriate use of a service, also provide data on the extent of acceptance of a service among those for whom it was designed. The proportion of people who have accepted an intervention can be calculated as follows:

- Survey of dropouts – dropouts are an extremely useful source of information for identifying ways of improving an intervention. These are the people who have gone through an intervention, have experienced both positives and negatives, and have then decided to withdraw. Talking to them can provide you with their first-hand experience of the programme. They are the people who can provide you with information on possible problems, either with the content of an intervention or with the way it has been delivered. They are also an excellent source of suggestions on how to improve a service. A survey, focus group discussion or in-depth interviews can provide valuable information about the strengths as well as weaknesses of a programme. Issues raised by them and suggestions made may become the basis for improving that intervention.

- Survey of non-users of a service – Whereas a group of dropouts can provide extremely useful information about the problems with an intervention, non-users are important in understanding why some, for whom the programme was designed, have not accepted it. Choose any method, quantitative or qualitative, to collect information from them. Of course it could be a problem to identify the non-users in a community.

4. Evaluating service delivery manner

There are situations when a programme may not have achieved its intended goals. In such situations, there are two possible causes: the content of the intervention and the way it is being delivered. It is to make sure that an intervention is being delivered effectively that you undertake process evaluation. It involves identifying problems with the way a service is being delivered to consumers or finding ways of improving the delivery system. Evaluating the delivery manner of a programme is a very important aspect of process evaluation. There are a number of issues in delivering a service that may impact upon its delivery manner and process evaluation considers them. Some of the issues are:

- the delivery manner per se;

- the contents of the service and its relevance to the needs of consumers;

- the adequacy and quality of training imparted to service providers to enable them to undertake various tasks;

- staff morale, motivation and interest in the programme, and ways of enhancing these;

- the expectations of consumers;

- resources available and their management;

- issues relating to access to services by the target population;

- ways of further improving the delivery of a service.

A process evaluation aims at studying some or all of these issues. There are a number of strategies that are used in process evaluation. The purpose for which you are going to use the findings should determine whether you adopt a quantitative or qualitative approach. Considerations that determine the use of qualitative or quantitative methods in general also apply in evaluation studies. Methods that can be used in undertaking a process evaluation are:

- Opinion of consumers – One of the best indicators of the quality of a service is how the consumers of that service feel about it. They are best placed to identify problems in the delivery manner, to point out its strengths and weaknesses, and to tell you how the service can be improved to meet their needs. simply by gathering the experiences of consumers with respect to utilisation of a service you can gain valuable information about its strengths and weaknesses. consumer surveys give you an insight into what the consumers of a service like and do not like about a service. in the present age of consumerism it is important to take their opinions into consideration when designing, delivering or changing a service.

If you want to adopt a qualitative approach to evaluation, you can use in-depth interviewing, focus group discussions and/or target population forums as ways of collecting information about the issues mentioned above. if you prefer to use a quantitative approach you can undertake a survey, giving consideration to all the aspects of quantitative research methodology including sample size and its selection, and methods of data collection. Keep in mind that qualitative methods will provide you with a diversity of opinions and issues but will not tell you the extent of that diversity. If you need to determine the extent of these issues, you should combine qualitative and quantitative approaches.

- Opinions of service providers – Equally important in process evaluation studies are the opinions of those engaged in providing a service. Service providers are fully aware of the strengths and weaknesses of the way in which a programme is being delivered. They are also well informed about what could be done to improve inadequacies. As an evaluator, you will find invaluable information from service providers for improving the efficiency of a service. Again, you can use qualitative or quantitative methods for data collection and analysis.

- Time-and-motion studies – Time-and-motion studies, both quantitative and qualitative, can provide important information about the delivery process of a service. The dominant technique involves observing the users of a service as they go through the process of using it. You, as an evaluator, passively observe each interaction and then draw inferences about the strengths and weaknesses of service delivery.

in a qualitative approach to evaluation you mainly use observation as a method of data collection, whereas in a quantitative approach you develop more structured tools for data collection (even for observation) and subject the data to appropriate statistical analysis in order to make inferences.

- Functional analysis studies – Analysis of the functions performed by service providers is another approach people use in the search for increased efficiency in service delivery. An observer, with expertise in programme content and the process of delivering a service, follows a client as s/he goes through the process of receiving it. The observer keeps note of all the activities undertaken by the service provider, with the time spent on each of them. Such observations become the basis for judging the desirability of an activity as well as the justification for the time spent on it, which then becomes the basis of identifying ‘waste’ in the process.

Again, you can use qualitative or quantitative methods of data collection. You can adopt very flexible methods of data collection or highly structured ones. You should be aware that observations can be very structured or unstructured. The author was involved in a functional analysis study which involved two-minute observations of activities of health workers in a community health programme.

- Panel of experts – Another method that is used to study the delivery process of a service is to ask experts in the area of that service to make recommendations about the process. These experts may use various methods (quantitative or qualitative) to gather information, and supplement it with their own knowledge. They then share their experiences and assessments with each other in order to come up with recommendations.

The use of multiple methods may provide more detailed and possibly better information but would depend upon the resources at your disposal and the purpose of your evaluation. Your skills as an evaluator lie in selecting a method (or methods) that best suits the purpose of evaluation within the given resources.

5. Impact/outcome evaluation

Impact or outcome evaluation is one of the most widely practised types of evaluation. It is used to assess what changes can be attributed to the introduction of a particular intervention, programme or policy. It establishes causality between an intervention and its impact, and estimates the magnitude of this change(s). It plays a central role in decision making by practitioners, managers, administrators and planners who wish to determine whether or not an intervention has achieved its desired objectives in order to make an informed decision about its continuation, termination or alteration. Many funding organisations base their decisions about further funding for programmes on impact evaluations. Specifically, an outcome evaluation is for the purpose of:

- establishing causal links between intervention inputs and outcomes;

- measuring the magnitude of these outcomes;

- determining whether a programme or intervention has achieved its intended goals;

- finding out the unintended effects, if any, of an intervention;

- comparing the impacts of an intervention with an alternative one in order to choose the more effective of the two.

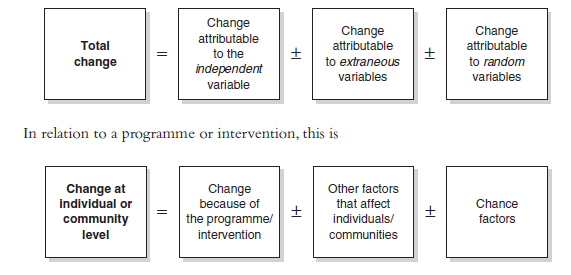

As you are aware, in any cause-and-effect relationship, in addition to the cause there are many other factors that can affect the relationship. (For details see Chapter 7.) Just to refresh your memory:

This theory of causality is of particular relevance to impact assessment studies. In determining the impact of an intervention, it is important to realise that the changes produced by an intervention may not be solely because of the intervention. Sometimes, other factors (extraneous variables) may play a more important role than the intervention in bringing about changes in the dependent variable. When you evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention, without comparing it to that of a control group, your findings will include the effects of extraneous variables. If you want to separate out the respective contributions of extraneous variables and the intervention, you need to use a control study design.

There are many designs from which you can choose in conducting an impact assessment evaluation. Impact assessment studies range from descriptive ones — in which you describe people’s experiences and perceptions of the effectiveness of an intervention — to random—control—blind experiments. Again, your choice of a particular design is dependent upon the purpose of the evaluation and resources available. Some of the commonly used designs are:

After-only design – Though technically inappropriate, after-only design is a commonly used design in evaluation studies. it measures the impact of a programme or intervention (after it has occurred) without having a baseline. The effectiveness of the intervention is judged on the basis of the current picture of the state of evaluation indicators. it relies on indicators such as:

- number of users of the service;

- number of dropouts from the service;

- satisfaction of clients with the service;

- stories/experiences of clients that changed them;

- assessment made by experts in the area;

- the opinions of service providers.

It is on the basis of findings about these outcome indicators that a decision about continuation, termination or alterations in an intervention is made. One of the major drawbacks of this design is that it does not measure change that can be attributed to the intervention as such, since (as mentioned) it has neither a baseline nor a control group to compare results with. However, it provides the current picture in relation to the outcome indicators. This design is therefore inappropriate when you are interested in studying the impact of an intervention per se.

- Before-and-after design – The before-and-after design is technically sound and appropriate for measuring the impact of an intervention. There are two ways of establishing the baseline. One way is where the baseline is determined before the introduction of an intervention, which requires advance planning; and the other is where the baseline is established retrospectively, either from previous service records or through recall by clients of their situation before the introduction of the intervention. Retrospective construction of the baseline may produce less accurate data than after the data collection and hence may not be comparable. However, in the absence of anything better, it does provide some basis of comparison.

As you may recall, one of the drawbacks of this design is that the change measured includes change brought about by extraneous and change variables. Hence, this design, though acceptable and better than the after-only design, still has a technical problem in terms of evaluation studies. Also, it is more expensive than the after-only design.

- Experimental-control design – The before-and-after study, with a control group, is probably the closest to a technically correct design for impact assessment of an intervention. One of the biggest strengths of this design is that it enables you to isolate the impact of independent and extraneous variables. However, it adds the problem of comparability between control and experimental groups. Sometimes this problem of comparability can be overcome by forming the groups through randomisation. Unfortunately, complexity in its execution and increased cost restrict the use of this design for the average evaluation study. Also, in many situations it may not be possible to find or construct a suitable control group.

- Comparative study design – The comparative study design is used when evaluating two or more interventions. For comparative studies you can follow any of the above designs; that is, you can have a comparative study using after-only, before-and-after or experimental-control

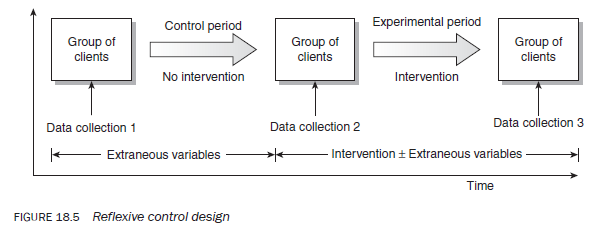

- Reflexive control design – To overcome the problem of comparability in different groups, sometimes researchers treat data collected during the non-intervention period to represent a control group, and information collected after the introduction of the intervention as if it pertained to an experimental group (Figure 18.5).

In the reflexive control design, comparison between data collection 2 and data collection 1 provides information for the control group, while comparison between data collection 3 and data collection 2 provides data for the experimental group. One of the main advantages of this design is that you do not need to ensure the comparability of two groups. However, if there are rapid changes in the study population over time, and if the outcome variables are likely to be affected significantly, use of this design could be problematic.

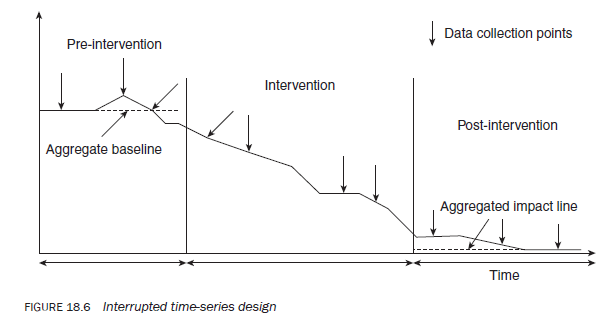

- Interrupted time-series design – In the interrupted time-series design you study a group of people before and after the introduction of an intervention. It is like the before-and-after design, except that you have multiple data collections at different time intervals to constitute an aggregated before-and-after picture (Figure 18.6). The design is based upon the assumption that one set of data is not sufficient to establish, with a reasonable degree of certainty and accuracy, the before-and-after situations.

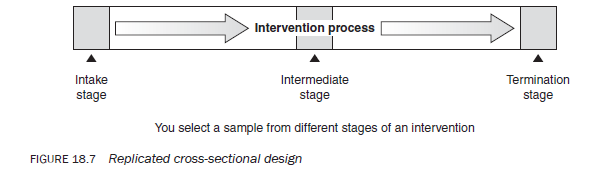

- Replicated cross-sectional design – The replicated cross-sectional design studies clients at different stages of an intervention, and is appropriate for those interventions that take new clients on a continuous or periodic basis. See Figure 18.7. This design is based on the assumption that those who are currently at the termination stage of an intervention are similar in terms of the nature and extent of the problem to those who are currently at the intake stage.

In order to ascertain the change that can be attributed to an intervention, a sample at the intake and termination stages of the programme is selected, so that information can be collected pertaining to pre-situations and post-situations with respect to the problem for which the intervention is being sought. To evaluate the pattern of impact, sometimes researchers collect data at one or more intermediary stages.

These designs vary in sophistication and so do the evaluation instruments. Choice of design is difficult and (as mentioned earlier) it depends upon the purpose and resources available.

Another difficulty is to decide when, during the intervention process, to undertake the evaluation. How do you know that the intervention has made its impact? One major difficulty in evaluating social programmes revolves around the question: was the change a product of the intervention or did it come from a consumer’s relationship with a service provider? Many social programmes are accepted because of the confidence consumers develop in a service provider. In evaluation studies you need to keep in mind the importance of a service provider in bringing about change in individuals.

6. Cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness evaluation

While knowledge about the process of service delivery and its outcomes is highly useful for an efficient and effective programme, in some cases it is critical to be informed about how intervention costs compare with outcomes. In today’s world, which is characterised by scarce resources and economic rationalism, it is important to justify a programme in relation to its cost. Cost-benefit analysis provides a framework for relating costs to benefits in terms of a common unit of measurement, monetary or otherwise. Specifically, cost-benefit analysis or cost-effectiveness evaluation is important because it helps to:

- put limited resources to optimal use;

- decide which of two equally effective interventions to replicate on a larger scale.

Cost-benefit analysis follows an input/output model, the quality of which depends upon the ability to identify accurately and measure all intervention inputs and outputs. Compared with technical interventions, such as those within engineering, social interventions are more difficult to subject to cost-benefit analysis. This is primarily because of the difficulties in accurately identifying and measuring inputs and outputs, and then converting them to a common monetary unit. Some of the problems in applying cost-benefit analysis to social programmes are outlined below:

- What constitutes an input for an intervention? There are direct and indirect inputs. Identifying these can sometimes be very difficult. Even if you have been able to identify them, the next problem is putting a price tag on each of them.

- Similarly, the outputs or benefits of an intervention need to be identified and measured. Like inputs, benefits can also be direct and indirect. In addition, a programme may have short-term as well as long-term benefits. How do you cost the various benefits of a programme? Another complexity is the need to consider benefits from the perspectives of different stakeholders.

- The main problem in cost-benefit analysis is the difficulty in converting inputs as well as outputs to a common unit. In social programmes, it often becomes difficult even to identify outputs, let alone measure and then convert them to a common unit of measurement.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

I am actually grateful to the holder of this web site who has shared this wonderful paragraph at at this place.

Pretty great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to

mention that I have truly loved surfing around your blog posts.

In any case I will be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again very soon!