Strategy defines the future direction and actions of an organization or part of an organization. Johnson and Scholes (2006) define corporate strategy as:

the direction and scope of an organization over the long-term: which achieves advantage for the organization through its configuration of resources within a changing environment to meet the needs of markets and to fulfil stakeholder expectations.

Lynch (2000) describes strategy as an organization’s sense of purpose. However, he notes that purpose alone is not strategy; plans or actions are also needed.

E-business strategies share much in common with corporate, business and marketing strategies. These quotes summarizing the essence of strategy could equally apply to each strategy:

- ‘Is based on current performance in marketplace.’

- ‘Defines how we will meet our objectives.’

- ‘Sets allocation of resources to meet goals.’

- ‘Selects preferred strategic options to compete within a market.’

- ‘Provides a long-term plan for the development of the organization.’

- ‘Identifies competitive advantage through developing an appropriate positioning defining a value proposition delivered to customer segments.’

Johnson and Scholes (2006) note that organizations have different levels of strategy, particularly for larger or global organizations. These are summarized within Figure 5.1. They identify corporate strategy which is concerned with the overall purpose and scope of the organization, business unit strategy which defines how to compete successfully in a particular market and operational strategies which are concerned with achieving corporate and business unit strategies. Additionally, there are what can be described as functional strategies that describe how the corporate and business unit strategies will be operationalized in different functional areas or business processes. Functional or process strategies refer to marketing, supply chain management, human resources, finance and information systems strategies. Where does e-business strategy fit? Figure 5.1 does not show at which level e-business strategy should be defined, since for different organizations this must be discussed and agreed. We can observe that there is a tendency for e-business strategy to be incorporated within the functional strategies, for example within a marketing plan or logistics plan, or as part of information systems (IS) strategy. A danger with this approach is that e-business strategy may not be recognized at a higher level within organizational planning. A distinguishing feature of organizations that are leaders in e-business, such as Cisco, Dell, HSBC, easyJet and General Electric, is that e-business is an element of corporate strategy development.

There is limited research on how businesses have integrated e-business strategy into existing strategy, although authors such as Doherty and McAulay (2002) have suggested it is important that e-commerce investments be driven by corporate strategies. We return to approaches of alignment later in the chapter.

1. The imperative for e-business strategy

Think about the implications if e-business strategy is not clearly defined. The following may result:

- Missed opportunities from lack of evaluation of opportunities or insufficient resourcing of e-business initiatives. These will result in more savvy competitors gaining a competitive advantage;

- Inappropriate direction of e-business strategy (poorly defined objectives, for example, with the wrong emphasis on buy-side, sell-side or internal process support);

- Limited integration of e-business at a technical level resulting in silos (separate organizational team with distinct responsibilities which does not work in an integrated manner with other teams) of information in different systems;

- Resource wastage through duplication of e-business development in different functions and limited sharing of best practice. For instance, each business unit or region may develop a separate web site with different suppliers without achieving economies of scale.

To help avoid these typical problems of implementing e-business in traditional organizations, organizations will want e-business strategy to be based on corporate objectives such as which markets to target and targets for revenue generation from electronic channels. As Rowley (2002) has pointed out, it is logical that e-business strategy should support corporate strategy objectives and it should also support functional marketing and supply chain management strategies.

However, these corporate objectives should be based on new opportunities and threats related to electronic network adoption, which are identified from environment analysis and objectives defined in an e-business strategy. So it can be said that e-business strategy should not only support corporate strategy, but should also influence it. Figure 5.2 explains how e-business strategy should relate to corporate and functional strategies. It also shows where these topics are covered in this book.

2. E-channel strategies

An important aspect of e-business strategies is that they create new ‘e-channel strategies’ for organizations.

E-channel strategies define specific goals and approaches for using electronic channels. This is to prevent simply replicating existing processes through e-channels, which will create efficiencies but will not exploit the full potential for making an organization more effective through e-business. Without specific goals and strategies to communicate the benefit of e-channels for customers and partners, adoption of the new channels will be slow relative to a structured approach. We will see in the section on objective setting that key metrics about online contribution can be set which suggest the percentage and value of leads, sales, services and purchases that are facilitated through e-commerce transactions. E-channel strategies also need to define how electronic channels are used in conjunction with other channels as part of a multi-channel e-business strategy. This multi-channel e-business strategy defines how different marketing and supply chain channels should integrate and support each other in terms of their proposition development and communications based on their relative merits for the customer and the company. Finally, we also need to remember that e-business strategy also defines how an organization gains value internally from using electronic networks, such as sharing employee knowledge and improving process efficiencies through intranets. Myers et al. (2004) provide a useful summary of the decisions required about multi-channel marketing.

The characteristics of a multi-channel e-business strategy are:

- E-business strategy is a channel strategy;

- Specific e-business objectives need to be set to benchmark adoption of e-channels;

- E-business strategy defines how we should:

- Communicate the benefits of using e-channels

- Prioritize audiences or partners targeted for e-channel adoption

- Prioritize products sold or purchased through e-channel

- Achieve our e-channel targets;

- E-channel strategies thrive on creating differential value for all parties to a transaction;

- But e-channels do not exist in isolation, so we still need to manage channel integration and acknowledge that the adoption of e-channels will not be appropriate for all products or services or generate sufficient value for all partners. This selective adoption of e-channels by business according to product or stakeholder preference is sometimes referred to as ‘rightchannelling’ in a sell-side e-commerce context. Right-channelling can be summarized as:

- Reaching the right customer

- Using the right channel

- With the right message or offering

- At the right time;

- E-business strategy also defines how an organization gains value internally from using electronic networks, such as through sharing employee knowledge and improving process efficiencies through intranets.

As an example of how an e-channel strategy is implemented and communicated to an audience, see Mini Case Study 5.1: BA asks ‘Have you clicked yet?’ This shows how BA communicates its new e-channel strategy to its customers in order to show them the differential benefits of their using the channel, and so change their behaviour. BA would use ‘right-channelling’ by targeting a younger, more professional audience for adoption of e-channels, while using traditional channels of phone and post to communicate with less web-savvy customers who prefer to use these media.

3. Strategy process models for e-business

Before developing any type of strategy, a management team needs to agree the process they will follow for generating and then implementing the strategy. A strategy process model provides a framework that gives a logical sequence to follow to ensure inclusion of all key activities of e-business strategy development. It also ensures that e-business strategy can be evolved as part of a process of continuous improvement.

Before the advent of e-business, many strategy process models had been developed for the business strategies described above. To what extent can management teams apply these models to e-business strategy development? Although strategy process models differ in emphasis and terminology, they all have common elements. Complete Activity 5.1 to discuss what these common elements are.

Through considering alternative strategy process models such as those of Table 5.1, common elements are apparent:

- Internal and external environment scanning or analysis is needed. Scanning occurs both during strategy development and as a continuous process in order to respond to competitors.

- A clear statement of vision and objectives is required. Clarity is required to communicate the strategic intention to both employees and the marketplace. Objectives are also vital to act as a check as to whether the strategy is successful!

- Strategy development can be broken down into strategy option generation, evaluation and selection. An effective strategy will usually be based on reviewing a range of alternatives and selecting the best on its merits.

- After strategy development, enactment of the strategy occurs as strategy implementation.

- Control is required to monitor operational and strategy effectiveness problems and adjust the operations or strategy accordingly.

Additionally, the models suggest that these elements, although generally sequential, are also iterative and require reference back to previous stages. In reality there is overlap between these stages.

To what extent, then, can this traditional strategy approach be applied to e-business? We will now review some suggestions for how e-business strategy should be approached.

Hackbarth and Kettinger (2000) suggest a four-stage ‘strategic e-breakout’ model with stages of:

- Initiation

- Diagnosis of the industry environment

- Breakout to establish a strategic target

- Transition or plotting a migration path.

This model emphasizes the need to innovate away from traditional strategic approaches by using the term ‘breakout’ to show the need for new marketplace structures and business/rev- enue models (Chapter 2). A weakness of this approach is that it does not emphasize objective setting and control. However, Hackbarth and Kettinger’s paper is valuable in detailing specific e-business strategy development activities. For example, the authors suggest that company analysis and diagnosis should review the firm’s capabilities with respect to the customers, suppliers, business partnerships and technologies.

Deise et al. (2000) present a novel approach to developing e-business strategy. Their approach is based on work conducted for clients of management consultants Pricewater- houseCoopers. They suggest that the focus of e-business strategy will vary according to the evolutionary stage of e-business. Initially the focus will involve the enhancement of the selling channels (sell-side e-commerce), which then tends to be followed by value-chain integration (buy-side e-commerce), and creation of a value network.

Jelassi and Enders (2008) suggest that there are three key dimensions for defining e-business strategy:

- Where will the organization compete? (That is, within the external micro-environment.)

- What type of value will it create? (Strategy options to generate value through increased revenue or reduced costs with their primary choices of (1) a cost leadership position where a company competes primarily in terms of low prices and (2) a differentiated position where a company competes on the basis of superior products and services.)

- How should the organization be designed to deliver value? Includes internal structure and resources and interfaces with external companies.

Note the use of two-way arrows in Figure 5.4 to indicate that each stage is not discrete, but rather it involves referring backwards or forwards to other strategy elements. Each strategy element will have several iterations. The arrows in Figure 5.4 highlight an important distinction in the way in which strategy process models are applied. Referring to the work of Mintzberg and Quinn (1991), Lynch (2000) distinguishes between prescriptive and emergent strategy approaches. In the prescriptive strategy approach he identifies three elements of strategy – strategic analysis, strategic development and strategy implementation, and these are linked together sequentially. Strategic analysis is used to develop a strategy, and it is then implemented. In other words, the strategy is prescribed in advance. Alternatively, the distinction between the three elements of strategy may be less clear. This is the emergent strategy approach where strategic analysis, strategic development and strategy implementation are interrelated.

In reality, most organizational strategy development and planning processes have elements of prescriptive and emergent strategy reflecting different planning and strategic review timescales. The prescriptive elements are the structured annual or six-monthly budgeting process or a longer-term 3-year rolling marketing planning process. But, on a shorter timescale, organizations naturally also need an emergent process to enable strategic agility (introduced in Chapter 2) and the ability to rapidly respond to marketplace dynamics. Econsultancy (2008a) has researched approaches used to encourage emergent strategies or strategic agility (see Chapter 3) based on interviews with e-commerce practitioners. Some of the approaches used by companies to support emergent strategy development are summarized in Table 5.2.

Kalakota and Robinson (2000) recommend a dynamic emergent strategy process specific to e-business. The elements of this approach are shown in Figure 5.5. It essentially shares similar features to Figure 5.4, but with an emphasis on responsiveness with continuous review and prioritization of investment in new applications.

We will now examine each of the main strategy elements of Figure 5.4 in more detail.

Strategic analysis or situation analysis involves review of:

- the internal resources and processes of the company to assess its e-business capabilities and results to date in the context of a review of its activity in the marketplace;

- the immediate competitive environment (micro-environment), including customer demand and behaviour, competitor activity, marketplace structure and relationships with suppliers, partners and intermediaries as described in Chapter 2;

- the wider environment (macro-environment) in which a company operates; this includes economic development and regulation by governments in the form of law and taxes together with social and ethical constraints such as the demand for privacy. These macroenvironment factors, including the social, legal, economic and political factors, were reviewed in Chapter 4 and are not considered further in this chapter.

The elements of situation analysis for an e-business are summarized in Figure 5.6. For the effective, responsive e-business, as explained earlier, it is essential that situation analysis or environmental scanning be a continuous process with clearly identified responsibilities for performing the scanning and acting on the knowledge acquired.

In this section we start with the internal perspective of how a company currently uses technology and then we review the competitive environment.

4. Resource and process analysis

Resource analysis for e-business is primarily concerned with its e-business capabilities, i.e. the degree to which a company has in place the appropriate technological and applications infrastructure and financial and human resources to support it. These resources must be harnessed together to give efficient business processes.

Jelassi and Enders (2008) distinguish between analysis of resources and capabilities:

- Resources are the tangible and intangible assets which can be used in value creation. Tangible resources include the IT infrastructure, bricks and mortar and financial capital. Intangible resources include a company’s brand and credibility, employee knowledge, licences and patents.

- Capabilities represent the ability of a firm to use resources effectively to support value creation. They are dependent on the structure and processes used to manage e-business, for example, the process to plan, review and enhance e-channel performance through web analytics (Chapter 12).

4.1. Stage models of e-business development

Stage models are helpful in reviewing how advanced a company is in its use of information and communications technology (ICT) resources to support its processes. Stage models have traditionally been popular in the analysis of the current application of business information systems (BIS) within an organization. For example, the six-stage model of Nolan (1979) refers to the development of use of information systems within an organization from initiation with simple data processing through to a mature adoption of BIS with controlled, integrated systems. A simple example of a stage model was introduced in Figure 1.13.

When assessing the current use of ICT within a company it is instructive to analyse the extent to which an organization has implemented the technological infrastructure and support structure to achieve e-business. In an early model focusing on sell-side web site development, Quelch and Klein (1996) developed a five-stage model referring to the development of sell-side e-commerce. The stages remain relevant today, particularly for small and medium businesses to benchmark their adoption of the Internet compared to other companies. For existing companies the stages are:

- Image and product information – a basic ‘brochureware’ web site or presence in online directories;

- Information collection – enquiries are facilitated through online forms;

- Customer support and service – ‘web self-service’ is encouraged through frequently asked questions and the ability to ask questions through a forum or online;

- Internal support and service – a marketing intranet is created to help with support process;

- Transactions – financial transactions such as online sales where relevant or the creation of an e-CRM system where customers can access detailed product and order information through an extranet.

Considering sell-side e-commerce, Chaffey et al. (2009) suggest there are six choices for a company deciding on which marketing services to offer via an online presence:

- Level 0: No web site or presence on web.

- Level 1: Basic web presence. Company places an entry in a web site, listing company names such as yell.co.uk to make people searching the web aware of the existence of the company or its products. There is no web site at this stage.

- Level 2: Simple static informational web site. Contains basic company and product information, sometimes referred to as ‘brochureware’.

- Level 3: Simple interactive site. Users are able to search the site and make queries to retrieve information such as product availability and pricing. Queries by e-mail may also be supported.

- Level 4: Interactive site supporting transactions with users. The functions offered will vary according to company. They will usually be limited to online buying. Other functions might include an interactive customer service helpdesk which is linked into direct marketing objectives.

- Level 5. Fully interactive site supporting the whole buying process. Provides relationship marketing with individual customers and facilitating the full range of marketing exchanges.

Research by Arnott and Bridgewater (2002) assessed the stages of sell-side e-commerce adoption reached by different businesses. They tested whether companies of different sectors and sizes and located in different countries had reached one of three stages. These were informational (information only – level 2 above), facilitating (relationship building – level 3 above) and transactional (online exchange – level 4 above). They found that a majority of firms were still using the Internet for information provision. This is also supported by the more recent research published in 2007 (Figure 1.10 and Figure 4.7). The main factors affecting the stage adopted was the size of the company and whether the Internet was being used to support international sales – sophistication was greater in both of these cases. Stage models have also been applied to SME businesses where Levy and Powell (2003) reviewed different adoption ladders which broadly speaking have four stages of (1) publish, (2) interact, (3) transact and (4) integrate.

Considering buy-side e-commerce, the corresponding levels of product sourcing applications can be identified:

- Level I. No use of the web for product sourcing and no electronic integration with suppliers.

- Level II. Review and selection from competing suppliers using intermediary web sites, B2B exchanges and supplier web sites. Orders placed by conventional means.

- Level III. Orders placed electronically through EDI, via intermediary sites, exchanges or supplier sites. No integration between organization’s systems and supplier’s systems. Rekeying of orders into procurement or accounting systems necessary.

- Level IV. Orders placed electronically with integration of company’s procurement systems.

- Level V. Orders placed electronically with full integration of company’s procurement, manufacturing requirements planning and stock control systems.

In Chapter 6, the case of BHP Steel is an illustration of such a stage model.

We should remember that typical stage models of web-site development such as those described above are most appropriate to companies whose products can be sold online

through transactional e-commerce. In fact, stage models could be developed for a range of different types of online presence and business models each with different objectives. In Chapter 1, we identified the four major different types of online presence for marketing: (1) transactional e-commerce site, (2) services-oriented relationship-building web site, (3) brand-building site and (4) portal or media site. A stage model for increasing sophistication in each of these areas can be defined. As a summary to this section Table 5.3 presents a synthesis of stage models for e-business development. Organizations can assess their position on the continuum between stages 1 and 4 for the different aspects of e-business development shown in the column on the left.

When companies devise the strategies and tactics to achieve their objectives they may return to the stage models to specify which level of innovation they are looking to achieve in the future.

4.2. Application portfolio analysis

Analysis of the current portfolio of business applications within a business is used to assess current information systems capability and also to inform future strategies. A widely applied framework within information systems study is that of McFarlan and McKenney (1993) with the modifications of Ward and Griffiths (1996). Figure 5.7 illustrates the results of a portfolio analysis for a B2B company applied within an e-business context. It can be seen that current applications such as human resources, financial management and production-line management systems will continue to support the operations of the business and will not be a priority for future investment. In contrast, to achieve competitive advantage, applications for maintaining a dynamic customer catalogue online, online sales and collecting marketing intelligence about customer buying behaviour will become more important. Applications such as procurement and logistics will continue to be of importance in an e-business context.

Of course, the analysis will differ greatly according to the type of company; for a professional services company or a software company, its staff will be an important resource, hence systems that facilitate the acquisition and retention of quality staff will be strategic applications.

Portfolio analysis is also often used to select the most appropriate future Internet projects. It is applied in this way in the strategy definition section: Decision 1: E-business channel priorities.

A weakness of the portfolio analysis approach is that today applications are delivered by a single e-business software or enterprise resource planning application. Given this, it is perhaps more appropriate to define the services that will be delivered to external and internal customers through deploying information systems.

E-consultancy (2008a) uses a form of portfolio analysis as the basis for benchmarking current e-commerce capabilities and identifying strategic priorities. The six areas for benchmarking are:

- Digital channel strategy. The development of a clear strategy including situation analysis, goal setting, identification of key target markets and audience and identification of priorities for development of online services as described in this chapter and Chapter 8.

- Online customer acquisition. Strategies for gaining new customers online using alternative digital media channels shown in Figure 9.6, including search engine marketing, partner marketing and display advertising.

- Online customer conversion and experience. Approaches to improve online service levels and increase conversion to sales or other online outcomes.

- Customer development and growth. Strategies to encourage visitors and customers to continue using online services using tactics such as e-mail marketing and personalization.

- Cross-channel integration and brand development. Integrating online sales and service with customer communications and service interactions in physical channels such as traditional advertising, phone and in-store touchpoints.

- Digital channel governance. Issues in managing e-commerce services such as structure and resourcing including human resources and the technology infrastructure such as hardware and networking facilities to deliver these applications.

4.3. Organizational and IS SWOT analysis

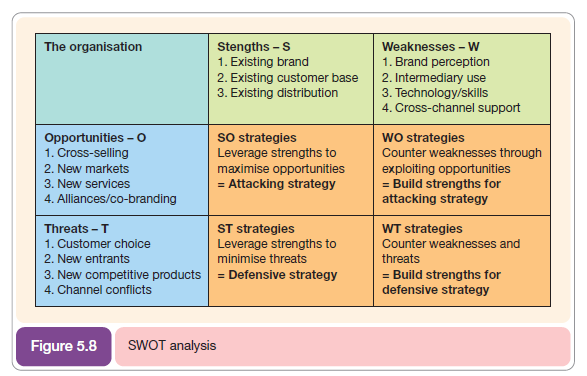

SWOT analysis is a relatively simple yet powerful tool that can help organizations analyse their internal resources in terms of strengths and weaknesses and match them against the external environment in terms of opportunities and threats. In an e-business context, a SWOT analysis of e-business-specific issues can combine SWOT related to corporate, marketing, supply chain and information systems, or a separate SWOT can be performed for each. SWOT analysis is of greatest value when it is used not only to analyse the current situation, but also as a tool to formulate strategies. To achieve this it is useful once the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats have been listed to combine them as shown in Figure 5.8. This format of SWOT is recommended over a typical four-box SWOT since it can be used to develop strategies to counter the threats and take advantage of the opportunities and can then be built into the e-business strategy.

Figure 8.6 gives an example of an e-marketing SWOT using the approach shown in Figure 5.8.

4.4. Human and financial resources

Resource analysis will also consider these two factors:

- Human resources. To take advantage of the opportunities identified in strategic analysis the right resources must be available to deliver e-business solutions. The importance of having a human resources approach that enables the recruitment and retention of staff is examined in Chapter 10, ‘Change management’. The need for new structures and cultures to achieve e-business is also covered.

- Financial resources. Assessing financial resources for information systems is usually conducted as part of investment appraisal and budgeting for enhancements to new systems which we consider later in the chapter.

Evaluation of internal resources should be balanced against external resources. Perrott (2005) provides a simple framework for this analysis (Figure 5.9). He suggests that adoption of e-business will be determined by the balance between internal capability and incentives and external forces and capabilities. Figure 5.9 defines a matrix where there are four quadrants which businesses within a market may occupy according to the development of their e-business strategy:

- Market driving strategy (high internal capabilities/incentives and low external forces/ incentives). This is often the situation for the early adopters. Perrott gives the examples of Amazon, Dell, Cisco and Wells Fargo Bank in this category.

- Capability building (low internal capabilities/incentives and high external forces/incen- tives). A later adopter.

- Market driven strategy. Internal capabilities/incentives and external forces/incentives are both high. Perrott gives the examples of Dun and Bradstreet, First Direct, Quicken and Reuters in this category.

- Status quo. This is the situation where there isn’t an imperative to change within the marketplace since both internal capabilities/incentives and external forces/incentives are low.

An organization’s position in the matrix will be governed by benchmarking of external factors suggested by Perrott (2005) which include the proportion of competitors’ products or services delivered electronically, proportion of competitors’ communications to customers done electronically, proportion of different customer segments (and suppliers or partners on the supply side) attracted to electronic activity. Internal factors to be evaluated include technical capabilities to deliver through internal or external IT providers, desire or ability to move from legacy systems and the staff capability (knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to conduct electronic business). The cost differential of savings made against implementation costs is also included here.

Stage models can also be used to assess internal capabilities and structures. For example, Atos Consulting (2008, Table 5.4) have defined a capability maturity framework. This is based on the well-known capability maturity models devised by Carnegie Mellon Software Engineering Institute (www.sei.cmu.edu/cmmi/) to help organizations improve their software development practices. In Chapter 10 there is more detail on how to achieve management of change between these stages.

5. Competitive environment analysis

As well as assessing the suitability of the internal resources of an organization for the move to e-business, external factors are also assessed as part of strategic analysis. We have already considered how marketplace analysis can be undertaken to identify external opportunities and threats for a business in Chapter 2, but here we consider demand analysis and look at competitive threats in more detail.

Demand analysis

A key factor driving e-business strategy objectives is the current level and future projections of customer, partner and internal access and usage of different types of e-commerce services, demand analysis. This is one of the main external factors referenced by Perrott (2005). In particular, demand analysis is a key activity in producing an e-marketing plan which will feed into the e-business strategy. It is described in more detail in Chapter 8.

Further information on demand for services will be indicated by data on the volume of searches as shown in Figure 2.12 for example.

For buy-side e-commerce a company also needs to consider the e-commerce services its suppliers offer: how many offer services for e-commerce and where they are located (e.g. direct with suppliers, in customer solutions or marketplaces – Chapter 7, p. 400).

6. Assessing competitive threats

Michael Porter’s classic 1980 model of the five main competitive forces that affect a company still provides a valid framework for reviewing threats arising in the e-business era. It is instructive to assess how the Internet may change the competitive environment. Table 5.5 summarizes the impact of the Internet on the five competitive forces. This table is a summary of the analysis by Michael Porter of the impact of the Internet on business using the five forces framework (Porter, 2001).

Placed in an e-business context, Figure 5.10 shows the main threats updated to place emphasis on the competitive threats applied to e-business. Threats have been grouped into buy-side (upstream supply chain), sell-side (downstream supply chain) and competitive threats. The main difference from the five forces model of Porter (1980) is the distinction between competitive threats from intermediaries (or partners) on the buy-side and sell-side. We will now review these e-business threats in more detail.

6.1. Competitive threats

- Threat of new e-commerce entrants

For traditional ‘bricks and mortar’ companies (Chapter 2, p. 88) this has been a common threat for retailers selling products such as books and financial services. For example, in Europe, traditional banks have been threatened by the entry of completely new start-up

competitors such as Zopa (www.zopa.com, which did not prove to be a viable business) or traditional companies from a different geographic market that use the Internet to facilitate their entry into an overseas market. Citibank (www.citibank.com), which successfully operates in the UK, has used this approach. ING, another existing financial services group, formed in 1991 and based in the Netherlands, has also used the Internet to facilitate market development. In May 2003, ING (www.ing.com) launched the online bank ING Direct in the UK (www.ingdirect.co.uk). Since its launch in 1997 ING Direct has gained over 10 million customers worldwide through its online banking operations in the USA, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Australia and Canada. More recently, the Icelandic bank Landsbanki (www.landsbanki.is) is another example of a new entrant. These new entrants have been able to succeed in a short time since they do not have the cost of developing and maintaining a distribution network to sell their products and these products do not require a manufacturing base. In other words, the barriers to entry are low. However, to succeed, new entrants need to be market leaders in executing marketing and customer service. The costs of achieving these will be high. These could perhaps be described as barriers to success rather than barriers to entry. This competitive threat is less common in vertical business-to- business markets involving manufacture and process industries such as the chemical or oil industry since the investment barriers to entry are much higher.

- Threat of new digital products

This threat can occur from established or new companies. The Internet is particularly good as a means of providing information-based services at a lower cost. The greatest threats are likely to occur where digital product fulfilment can occur over the Internet, as is the case with delivering share prices, digital media content or software. This may not affect many business sectors, but is vital in some, such as newspaper, magazine and book publishing, and music and software distribution. In photography, Kodak has responded to a major threat of reduced demand for traditional film by increasing its range of digital cameras to enhance this revenue stream and by providing online services for customers to print and share digital photographs. The extent of this threat can be gauged by a review of product in the context of Figure 5.10.

- Threat of new business models

This threat can also occur from established or new companies. It is related to the competitive threat in that it concerns new methods of service delivery. The threats from existing competitors will continue, with the Internet perhaps increasing rivalry since price comparison is more readily possible and the rival e-businesses can innovate and undertake new product development and introduce alternative business and revenue models with shorter cycle times than previously. This again emphasizes the need for continual environment scanning. See the section on business and revenue models in Chapter 2 for examples of strategies that can be adopted in response to this threat. Case Study 2.3 about Zopa shows how a new peer-to-peer lending model has changed the loans market.

6.2. Sell-side threats

- Customer power and knowledge

This is perhaps the single biggest threat posed by electronic trading. The bargaining power of customers is greatly increased when they are using the Internet to evaluate products and compare prices. This is particularly true for standardized products for which offers can be compared for different suppliers through price comparison engines provided by intermediaries such as Kelkoo (www.kelkoo.com) or PriceRunner (www.pricerunner.com). For commodities, auctions on business-to-business exchanges can also have a similar effect of driving down price. Purchase of some products that have not traditionally been thought of as commodities may become more price-sensitive. This process is known as ‘commoditization’. Examples of goods that are becoming commoditized are electrical goods and cars. The issue of online pricing is discussed in Chapter 8.

In the business-to-business arena, a further issue is that the ease of use of the Internet channel makes it potentially easier for customers to swap between suppliers – switching costs are lower. With the Internet, which offers a more standard method for purchase through web browsers, the barriers to swapping to another supplier will be lower. With a specific EDI (electronic data interchange) link that has to be set up between one company and another, there may be reluctance to change this arrangement (soft lock-in due to switching costs). Commentators often glibly say‘online, your competitor is only a mouse click away’ but it should be remembered that soft lock-in still exists on the web – there are still barriers and costs to switching between suppliers since once a customer has invested time in understanding how to use a web site to select and purchase a particular type of product, they may not want to learn another service.

- Power of intermediaries

A significant downstream channel threat is the potential loss of partners or distributors if there is a channel conflict resulting from disintermediation (Chapter 2, p. 65). A good example of the tensions between intermediaries, and in particular aggregators and strategies to resolve them is shown by the public discussion between direct insurer DirectLine (www.directline.com) and aggregator MoneySupermarket (www.moneysupermarket.com) highlighted in Box 5.2.

An additional downstream threat is the growth in number of intermediaries (another form of partners) to link buyers and sellers. These include consumer portals such as Bizrate (www.bizrate.com) and business-to-business exchanges such as EC21 (www.ec21.com). This threat links to the rivalry between competitors. If a company’s competitors are represented on a portal while the company is absent or, worse still, they are in an exclusive arrangement with a competitor, then this can potentially exclude a substantial proportion of the market. For example, in the billion-dollar market involved in the verification of consumer products and business shipments such as oil, chemicals and grain, Integrated Testing Services (www.itsgroup.com) found that its main rival, the Swiss SGS Group (Societe Generale de Surveillance, www.sgsgroup.com) had signed an exclusive arrangement for verification of cars on the Carbuster site. Despite its vintage, SGS has proved adaptable to the new trading environment and has set up its own verification portal (SGS Online certification, www.sgsonline.com) which offers a Gold Seal ‘kitemark’ that is indicative of‘an extremely good likelihood that sellers so rated would satisfy their buyers’ requirements on pre-defined aspects of quality, quantity or delivery’. This is an example of countering new intermediaries, sometimes referred to as a ‘countermediation strategy’. Through seizing opportunities SGS pre-empted threats from existing competitors such as ITS and start-ups such as UK-based Clicksure.

6.3. Buy-side threats

- Power of suppliers

This can be considered as an opportunity rather than a threat. Companies can insist, for reasons of reducing cost and increasing supply chain efficiency, that their suppliers use electronic links such as EDI or Internet EDI to process orders. Additionally, the Internet tends to reduce the power of suppliers since barriers to migrating to a different supplier are reduced, particularly with the advent of business-to-business exchanges. However, if suppliers insist on proprietary technology to link companies, then this creates ‘soft lock-in’ due to the cost or complexity of changing supppliers.

- Power of intermediaries

Threats from buy-side intermediaries such as business-to-business exchanges are arguably less than those from sell-side intermediaries, but risks arising from using these services should be considered. These include the cost of integration with such intermediaries, particularly if different standards of integration are required for each. They may pose a threat from increasing commission once they are established.

From the review above, it should be apparent that the extent of the threats will be dependent on the particular market a company operates in. Generally the threats seem to be greatest for companies that currently sell through retail distributors and have products that can be readily delivered to customers across the Internet or by parcel. Case Study 5.1 highlights how one company has analysed its competitive threats and developed an appropriate strategy.

7. Co-opetition

Jelassi and Enders (2008) note that while the five forces framework focuses on the negative effects that market participants can have on industry attractiveness, the positive interactions that competitors within an industry can have a positive effect on profitability. Examples of interactions encouraged through co-opetition which Jelassi and Enders mention include:

- Joint standards setting for technology and other industry standards. For example, competitors within mobile commerce can encourage development of standard approaches such as 3G which potential customers can be educated about and to make it easier to enable customer switching.

- Joint developments for improving product quality, increasing demand or smoothing e-procurement. For example, competing car manufacturers DaimlerChrysler, Ford and General Motors set up Covisint, a common purchasing platform (Chapter 7).

- Joint lobbying for favourable legislation, perhaps through involvement in trade associations.

8. Competitor analysis

Competitor analysis is also a key aspect of e-business situation analysis, but since it is also a key activity in producing an e-marketing plan which will feed into the e-business strategy; this is also described in more detail in Chapter 8.

Resource-advantage mapping

Once the external opportunities and internal resources have been reviewed, it is useful to map the internal resource strengths against external opportunities, to identify, for example, where competitors are weak and can be attacked. To identify internal strengths, definition of core competencies is one approach. Lynch (2000) explains that core competencies are the resources, including knowledge, skills or technologies that provide a particular benefit to customers, or increase customer value relative to competitors. Customer value is defined by Deise et al. (2000) as dependent on product quality, service quality, price and fulfilment time. So, to understand core competencies we need to understand how the organization is differentiated from competitors in these areas. Benchmarking e-commerce services of competitors, as described in Chapter 8, is important here. The cost-base of a company relative to its competitors’ is also important since lower production costs will lead to lower prices. Lynch (2000) argues that core competencies should be emphasized in objective setting and strategy definition.

Source: Dave Chaffey (2010), E-Business and E-Commerce Management: Strategy, Implementation and Practice, Prentice Hall (4th Edition).

You should take part in a contest for one of the best blogs on the web. I will recommend this site!

I love it when people get together and share ideas. Great website, stick with it.