There are several quite different reasons for wanting to decipher or assess an organizational culture. At one extreme is pure academic research where the researcher is trying to present a picture of a culture to fellow researchers and other interested parties to develop theory or test some hypothesis. This covers most anthropologists who go to live in a culture to get an insider’s view and then present the culture in written form for others to get a sense of what goes on there (for example, Dalton, 1959; Kunda, 1992; Van Maanen, 1973).

At the other extreme is the student’ s need to assess the culture of an organization to decide whether or not to work there, or the need of an employee or manager to understand his or her organization better in order to improve it. In between is the consultant ’s and change agent’s need to decipher the culture to facilitate some change program that the organization has launched to solve a business problem. What differs greatly in these cases is the focus and level of depth involved in the deciphering and who needs to know the results. At the end of this chapter, we will also discuss the ethical issues and risks involved in each of these approaches.

1. Deciphering from the Outside

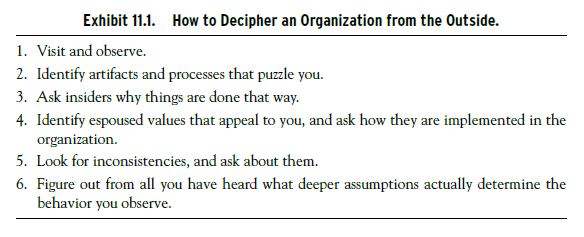

It is not only the ethnographer or researcher who needs to decipher an organization’s culture. The job applicant, the customer, and the journalist all have the need from time to time to figure out what goes on inside a particular organization. They do not need to know the totality of a given culture, but they need to know some of its essences in relation to their goal. The commonest version of this need is the graduate wanting to know whether or not to go to work in a particular organization. Exhibit 11.1 shows the major activities that might be involved in such deciphering.

The essential point is not to get too involved with the content of the culture until you have experienced it at the artifact level. That means visiting the public aspects, taking tours, asking to see inside areas, and reading whatever literature the organization makes available. The first cut at thinking about content areas should come out of the things that puzzle you. Why are the offices laid out the way they are, why is it so quiet or noisy, why are there no pictures on the walls, and so on? Your personal needs and interests should guide this process, not some formal checklist. To give yourself some content focus, try to observe how the insiders behave toward each other in terms of the critical issues of authority and intimacy.

You will have met some insiders in the process—recruiters, customer representatives, tour guides, friends who work there or friendly strangers with whom you can strike up a conversation. When you interact with insiders, the culture will reveal itself in the way that the insiders deal with you. Culture is best revealed through interaction. Ask insiders about the things you have observed that puzzle you. To your surprise, they may be puzzled as well because insiders do not necessarily know why their culture works the way it does. But being jointly puzzled begins to give you some insight into the layers of the culture, and you can ask the same question of other insiders some of whom may be more insightful as to what is going on. If you have read all about the organization and have heard its claims about its goals and values, look for evidence that they are or are not being met, and ask insiders how those goals and values are met. If you discover inconsistencies, ask about those. Whenever you hear a generalization or an abstraction such as “we are a team here,” ask for some specific behavioral examples.

This process of deciphering cannot be standardized because organizations differ greatly in what they allow the outsider to see. Instead you have to think like the anthropologist, lean heavily on observation, and then follow up with various kinds of inquiry. The reason for focusing on things that puzzle you is that it keeps the inquiry pure. If you start with trying to verify your assumptions or stereotypes of the organization, you will be perceived as threatening and will elicit inaccurate defensive information. If you display genuine puzzlement, you will elicit efforts on the part of insiders to help you understand. In that regard, the best form of inquiry may be to reveal something that puzzles you and then say, “Help me to understand why the following things are happening….”

2. Deciphering in a Researcher Role

If you are a researcher trying to decipher what is going on in relation to a particular research question, your first issue is getting entry. In the process of contacting the organization, negotiating what you need and what you offer them in return, you will go through all of the preceding steps with the insiders whom you have already met. You will acquire a great deal of superficial but potentially relevant cultural knowledge. Depending on your research goals, you then have to decide what additional information to gather to get a deeper understanding of the culture.

You must realize that gathering valid data from a complex human system is intrinsically difficult, involves a variety of choices and options, and is always an intervention into the life of the organization.

The most obvious difficulty in gathering valid cultural data is the well- known phenomenon that when human “subjects” are involved in research, there is a tendency for the subjects either to resist and hide data that they feel defensive about or to exaggerate to impress the researcher or to get cathartic relief—“Finally someone is interested enough in us to listen to our story.” The need for such “cathartic relief” derives from the fact that even the best of organizations generate “toxins”—frustrations with the boss, tensions over missed targets, destructive competition with peers, scarce resources, exhaustion from overwork, and so on (Frost, 2003; Goldman, 2008).

In the process of trying to understand how the organization really works, you may find yourself listening to tales of woe from anxious or frustrated employees who have no other outlet. To get any kind of accurate picture of what is going on in the organization, you must find a method that encourages the insiders to “tell it like it is” rather than trying to impress you, hide data, or blow off steam.

If you have made any kind of contact with the organization, even if it is only getting permission to observe silently, the human system has been perturbed in unknown ways. The employees being observed may view you as a spy or as an opportunity for catharsis, as noted earlier. Motives will be attributed to management as to why you are there. You may be seen as a nuisance, a disturbance, or an audience to whom to play. But you have no way of knowing which of the many possible reactions you are eliciting and whether or not they are desirable either from a data gathering or ethical point of view. For this reason, you should examine carefully the broad range of data gathering interventions available and choose carefully which method to use.

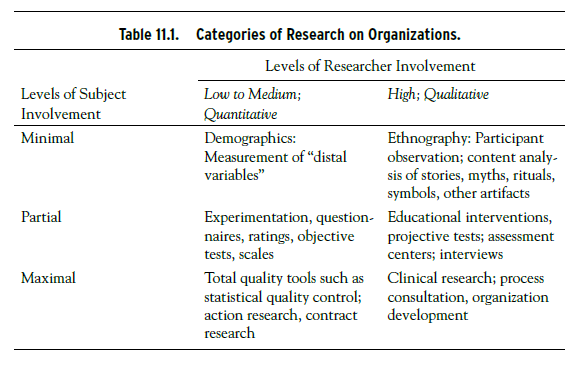

The many possible ways of gathering data are shown in Table 11.1. They differ along two dimensions—how involved the researcher becomes with the organization being studied and how involved the members of the organization become in the data gathering process.

Some cultural artifacts can be gathered by purely demographic methods or by observation at a distance, such as photographing buildings, observing action in the organization without getting involved, entering the organization incognito, and so on. As was pointed out in Chapter Two, the problem with this method is that the data may be clear but undecipherable. I could see all the fighting in DEC from a distance, but I had no idea what it meant.

If you want to understand more of what is going on, you must get more involved through becoming a participant observer/ethnographer, but you do not, in this role, want the subjects to become too directly involved lest you unwittingly change the very phenomena you are trying to study. To minimize the inevitable biases that result from your own involvement, you may use insiders as “informants” to help clarify what you observe or to decipher the data you are gathering, still limiting the organization ’s involvement as much as possible.

The middle row of Table 11.1 depicts data gathering methods that involve the members of the organization to a greater degree. If you still want to minimize your own outsider involvement, you try to rely on “objective” measurements such as experiments or questionnaires. Experiments are usually not possible for ethical reasons, but surveys and questionnaires are often used, with the limitations that were discussed in detail in the previous chapter. If you recognize that the interpretation of cultural data may require interaction with the subjects, you could use semistructured interviews, projective tests, or standardized assessment situations, but these methods again raise the ethical issues of whether you are intervening in their system beyond what they might have agreed to.

In an interview, you can ask broad questions such as the following:

- What was it like to come to work in this organization?

- What did you notice most as being important to getting along?

- How do bosses communicate their expectations?

The main problem with this approach is that it is very time consuming, and it may be hard to put data from different individuals together into a coherent picture because each person may see things differently even though he or she uses the same words.

The important point to remember is that after you have described the organization by abstracting “scores” from individual survey or interview responses, you have only a superficial understanding of the cultural dynamics that may be operating. That level of understanding may be enough to compare many organizations but can be quite useless if you are trying to understand a particular organization in any kind of depth. For example, DEC, HP, and Apple would have looked very similar on culture surveys as being very decentralized, innovative, employee centered, constructive, and self-actualizing, yet were quite different at the level of basic assumptions. In DEC, you fought everything out and were personally responsible to “do the right thing;” in HP, you had to publicly be nice but develop competitive and political skills to get things done; and in Apple, you were in a project, not a company, and you were free to “do your own thing.”

Even more important, the three companies had very different strategies, which were also embedded in their cultures but would have been hard to measure. DEC was creating a new concept of computing with its evolution of the minicomputer. HP was an instrumentation company that went into computing and ended up with major subcultures that eventually split into Agilent and HP. Apple wanted to evolve a simpler model of computing for school kids and a “fun” model of computing for “yuppies” and shunned marketing to government and big business early in its life. These cultural differences in strategy can be seen in HP and Apple today in their different product sets and marketing styles but would only have been observed in the group interactions of senior executives. Ciba-Geigy’s obsession with science and technology only surfaced from their reaction to Airwick.

The dilemma for you, then, is how to get access to groups where the deeper cultural assumptions reveal themselves. The answer is that you must somehow motivate the organization to want to reveal itself to you because it has something to gain. That brings us to the bottom row of Table 11.1 and the concepts of action research and clinical research. Action research is generally thought of as a process where the members of the organization being studied become involved in the gathering of data and, especially, in the interpretation of what is found. If the motivation for the project is to help the researcher gather valid data, the action research label is appropriate. However, if the project was initiated by the organization to solve a problem, we move to the lower-right corner of the table into what I have called “clinical research or inquiry” (Schein, 1987a, 2001, 2008).

Clinical Research: Deciphering in a Consultant/Helper Role. In the bottom-right cell of Table 11.1 is the methodology that I believe is most appropriate to cultural deciphering if you want to get to the deeper levels and the cultural pattern. This level of analysis can be achieved if the organization needs some kind of help from you and if you are trying to help the organization understand itself better to make changes. Your deeper insight into the culture is then a byproduct of your helping.

Most of the information I have provided so far about cultural assumptions in different kinds of organizations was gathered as a byproduct of my consulting with those organizations. The critical distinguishing feature of this inquiry model is that the data come voluntarily from the members of the organization because either they initiated the process and have something to gain by revealing themselves to you, the outsider, or, if you initiated the project, they feel they have something to gain from cooperating with you. In other words, no matter how the contact was initiated, the best cultural data will surface if the members of the organization feel they are getting some help from you.

If you are an ethnographer/researcher, you must analyze carefully what you may genuinely have to offer the organization and work toward a psychological contract in which the organization benefits in some way or, in effect, becomes a client. This way of thinking requires you to recognize from the outset that your presence will be an intervention in the organization and that the goal should be how to make that intervention useful to the organization.

Ethnographers tell stories of how they were not “accepted” until they became helpful to the members of the organization in some way, by either doing a job that needed to be done or contributing in some other way (Van Maanen, 1979a; Barley, 1988; Kunda, 1992). The contribution can be entirely symbolic and unrelated to the work of the group being studied. For example, Kunda reports that in his work in a DEC engineering group, he was “permitted” to study the group, but they were quite aloof, which made it hard to inquire about what certain rituals and events in the group meant. However, Kunda was a very good soccer player and was asked to join the lunchtime games. He made a goal for his team one day and from that day forward, he reports, his relationship to the group changed completely. He was suddenly “in” and “of” the group, and that made it possible to ask about many issues that had previously been off limits.

Barley (1988), in his study of the introduction of computerized tomography into a hospital radiology department, offered himself as a working member of the team and was accepted to the extent that he actually contributed in various ways to getting the work done. The important point is to approach the organization with the intention of helping, not just gathering data.

Alternatively, a consultant may be invited into the organization to help with some problem that has been presented that initially has no relationship to culture. In the process of working on the problem, the consultant will discover culturally relevant information, particularly if the process consultation model is used, with its emphasis on inquiry and helping the organization to help itself (Schein, 1999a, 2009a).

If you are in the helper role, you are licensed to ask all kinds of questions that can lead directly into cultural analysis, and, thereby, allow the development of a research focus as well. Both you and the “client” become fully involved in the problem-solving process, and, therefore, the search for relevant data becomes a joint responsibility. It is then in the client’s interest to say what is really going on instead of succumbing to the potential biases of hiding, exaggerating, and blowing off steam. Furthermore, you again have the license to follow up, to ask further questions, and even to confront the respondent if you feel he or she is holding back.

In this clinical helping role, you are not limited to the data that surface around the client’s specific issues. There will usually be many opportunities to hang around and observe what else is going on, allowing you to combine some of the best elements of the clinical and the participant observer ethnographic models. In fact, the ethnographic model when the ethnographer comes to be seen as a helper and the helper model as just described converge and become one and the same.

How Valid Are Clinically Gathered Data? How can you judge the “validity” of the data gathered by this clinical model? The validity issue has two components: (1) factual accuracy based on whatever contemporary or historical data you can gather, and (2) interpretative accuracy in terms of you representing cultural phenomena in a way that communicates what members of the culture really mean, rather than projecting into the data your own interpretations (Van Maanen, 1988). To fully understand cultural phenomena thus requires at least a combination of history and clinical research, as some anthropologists have argued persuasively (Sahlins, 1985).

Factual accuracy can be checked by the usual methods of triangulation, multiple sources, and replication. Interpretative accuracy is more difficult, but three criteria can be applied. First, if the cultural analysis is “valid,” an independent observer going into the same organization should be able to see the same phenomena and interpret them the same way. Second, if the analysis is valid, you should be able to predict the presence of other phenomena and anticipate how the organization will handle future issues. In other words, predictability and replication become the key validity criteria. Third, the members of the organization should feel comfortable that what you have depicted makes sense to them and helps them to understand themselves.

The clinical model makes explicit two fundamental assumptions: (1) it is not possible to study a human system without intervening in it, and (2) we can only fully understand a human system by trying to change it (Lewin, 1947). This conclusion may seem paradoxical in that we presumably want to understand a system as it exists in the present. This is not only impossible because our very presence is an intervention that produces unknown changes, but if we attempt to make helpful changes, we will enable the system to reveal both its goals and its defensive routines, essential parts of its culture. For this process to work, the intervention goals must be jointly shared by the outsider and insider. If the consultant tries to change the organization in terms of his or her own goals, the risk of defensiveness and withholding of data rises dramatically. If the consultant is helping the organization to make some changes that it wants, the probability rises that organization members will reveal what is really going on. A more detailed analysis of how such a managed change process works is provided in Chapter Eighteen.

Source: Schein Edgar H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass; 4th edition.

a introduce text