Strategic fit requires that both the competitive and supply chain strategies of a company have aligned goals. It refers to consistency between the customer priorities that the competitive strategy hopes to satisfy and the supply chain capabilities that the supply chain strategy aims to build. For a company to achieve strategic fit, it must accomplish the following:

- The competitive strategy and all functional strategies must fit together to form a coordinated overall strategy. Each functional strategy must support other functional strategies and help a firm reach its competitive strategy goal.

- The different functions in a company must appropriately structure their processes and resources to be able to execute these strategies successfully.

- The design of the overall supply chain and the role of each stage must be aligned to support the supply chain strategy.

A company may fail either because of a lack of strategic fit or because its overall supply chain design, processes, and resources do not provide the capabilities to support the desired strategic fit. Consider, for example, a situation in which marketing is publicizing a company’s ability to provide a large variety of products quickly; simultaneously, distribution is targeting the lowest-cost means of transportation. In this situation, it is likely that distribution will delay orders so it can get better transportation economies by grouping orders together or using inexpensive but slow modes of transportation. This action conflicts with marketing’s stated goal of providing variety quickly. Similarly, consider a scenario in which a retailer has decided to provide a high level of variety while carrying low levels of inventory but has selected suppliers and carriers based on their low price and not their responsiveness. In this case, the retailer is likely to end up with unhappy customers because of poor product availability.

To elaborate on strategic fit, let us consider the evolution of Dell and its supply chain between 1993 and the present. Between 1993 and 2006, Dell’s competitive strategy was to provide a large variety of customizable products at a reasonable price. Given the focus on customization, Dell’s supply chain was designed to be very responsive. Assembly facilities owned by Dell were designed to be flexible and to easily handle the wide variety of configurations requested by customers. A facility that focused on low cost and efficiency by producing large volumes of the same configuration would not have been appropriate in this setting.

The notion of strategic fit also extended to other functions within Dell. Dell PCs were designed to use common components and to allow rapid assembly. This design strategy clearly aligned well with the supply chain’s goal of assembling customized PCs in response to customer orders. Dell worked hard to carry this alignment to its suppliers. Given that Dell produced customized products with low levels of inventory, it was crucial that suppliers and carriers be highly responsive. For example, the ability of carriers to merge a PC from Dell with a monitor from Sony allowed Dell not to carry any Sony monitors in inventory.

Starting in 2007, however, Dell altered its competitive strategy and had to change its supply chain accordingly. With a reduced customer focus on hardware customization, Dell branched out into selling PCs through retail stores such as Walmart. Through Walmart, Dell offers a limited variety of desktops and laptops. It is also essential that monitors and other peripherals be available in inventory because a customer buying a PC at Walmart is not willing to wait for the monitor to show up later. Clearly, the flexible and responsive supply chain that aligns well with customer needs for customization does not necessarily align well when customers no longer want customization but prefer low prices. Given the change in customer priorities, Dell has shifted a greater fraction of its production to a build-to-stock model to maintain strategic fit. Contract manufacturers like Foxconn that are focused on low cost now produce many of Dell’s products well in advance of sale. To maintain strategic fit, Dell’s supply chain has moved from a relentless focus on responsiveness to a greater focus on low cost.

1. How is Strategic Fit Achieved?

What does a company need to do to achieve that all-important strategic fit between the supply chain and competitive strategies? A competitive strategy will specify, either explicitly or implicitly, one or more customer segments that a company hopes to satisfy. To achieve strategic fit, a company must ensure that its supply chain capabilities support its ability to satisfy the needs of the targeted customer segments.

There are three basic steps to achieving this strategic fit, which we outline here and then discuss in more detail:

- Understanding the customer and supply chain uncertainty: First, a company must understand the customer needs for each targeted segment and the uncertainty these needs impose on the supply chain. These needs help the company define the desired cost and service requirements. The supply chain uncertainty helps the company identify the extent of the unpredictability of demand and supply that the supply chain must be prepared for.

- Understanding the supply chain capabilities: Each of the many types of supply chains is designed to perform different tasks well. A company must understand what its supply chain is designed to do well.

- Achieving strategic fit: If a mismatch exists between what the supply chain does particu larly well and the desired customer needs, the company will either need to restructure the supply chain to support the competitive strategy or alter its competitive strategy.

STEP 1: UNDERSTANDING THE CUSTOMER AND SUPPLY CHAIN UNCERTAINTY

To understand the customer, a company must identify the needs of the customer segment being served. Let us compare Seven-Eleven Japan and a discounter such as Sam’s Club (a part of Walmart). When customers go to Seven-Eleven to purchase detergent, they go there for the convenience of a nearby store and are not necessarily looking for the lowest price. In contrast, low price is very important to a Sam’s Club customer. This customer may be willing to tolerate less variety and even purchase large package sizes as long as the price is low. Even though customers purchase detergent at both places, the demand varies along certain attributes. In the case of Seven-Eleven, customers are in a hurry and want convenience. In the case of Sam’s Club, they want a low price and are willing to spend time getting it. In general, customer demand from different segments varies along several attributes, as follows:

- Quantity of the product needed in each lot: An emergency order for material needed to repair a production line is likely to be small. An order for material to construct a new production line is likely to be large.

- Response time that customers are willing to tolerate: The tolerable response time for the emergency order is likely to be short, whereas the allowable response time for the construction order is apt to be long.

- Variety of products needed: A customer may place a high premium on the availability of all parts of an emergency repair order from a single supplier. This may not be the case for the construction order.

- Service level required: A customer placing an emergency order expects a high level of product availability. This customer may go elsewhere if all parts of the order are not immediately available. This is not apt to happen in the case of the construction order, for which a long lead time is likely.

- Price of the product: The customer placing the emergency order is apt to be much less sensitive to price than the customer placing the construction order.

- Desired rate of innovation in the product: Customers at a high-end department store expect a lot of innovation and new designs in the store’s apparel. Customers at Walmart may be less sensitive to new product innovation.

Each customer in a particular segment will tend to have similar needs, whereas customers in a different segment can have very different needs.

Although we have described several attributes along which customer demand varies, our goal is to identify one key measure for combining all of these attributes. This single measure then helps define what the supply chain should do particularly well.

Implied Demand Uncertainty. At first glance, it may appear that each of the customer need categories should be viewed differently, but in a fundamental sense, each customer need can be translated into the metric of implied demand uncertainty, which is demand uncertainty imposed on the supply chain because of the customer needs it seeks to satisfy.

We make a distinction between demand uncertainty and implied demand uncertainty. Demand uncertainty reflects the uncertainty of customer demand for a product. Implied demand uncertainty, in contrast, is the resulting uncertainty for only the portion of the demand that the supply chain plans to satisfy based on the attributes the customer desires. For example, a firm supplying only emergency orders for a product will face a higher implied demand uncertainty than a firm that supplies the same product with a long lead time, as the second firm has an opportunity to fulfill the orders evenly over the long lead time.

Another illustration of the need for this distinction is the impact of service level. As a supply chain raises its level of service, it must be able to meet a higher and higher percentage of actual demand, forcing it to prepare for rare surges in demand. Thus, raising the service level increases the implied demand uncertainty even though the product’s underlying demand uncertainty does not change.

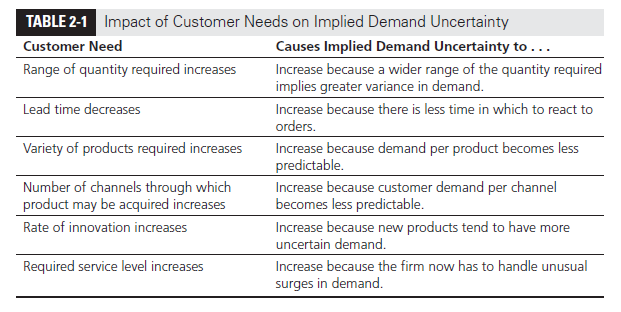

Both the product demand uncertainty and various customer needs that the supply chain tries to fill affect implied demand uncertainty. Table 2-1 illustrates how various customer needs affect implied demand uncertainty.

As each individual customer need contributes to the implied demand uncertainty, we can use implied demand uncertainty as a common metric with which to distinguish different types of demand.

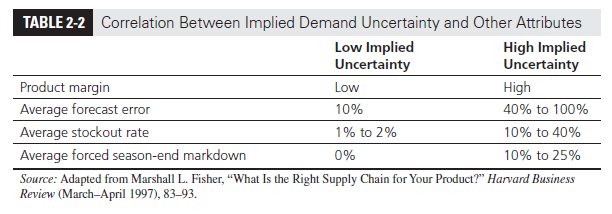

Fisher (1997) pointed out that implied demand uncertainty is often correlated with other characteristics of demand, as shown in Table 2-2. An explanation follows:

- Products with uncertain demand are often less mature and have less direct competition. As a result, margins tend to be high.

- Forecasting is more accurate when demand has less uncertainty.

- Increased implied demand uncertainty leads to increased difficulty in matching supply with demand. For a given product, this dynamic can lead to either a stockout or an oversupply situation. Increased implied demand uncertainty thus leads to both higher oversupply and a higher stockout rate.

- Markdowns are high for products with greater implied demand uncertainty because oversupply often results.

First, let us take an example of a product with low implied demand uncertainty—such as table salt. Salt has a low margin, accurate demand forecasts, low stockout rates, and virtually no markdowns. These characteristics match well with Fisher’s chart of characteristics for products with highly certain demand.

On the other end of the spectrum, a new cell phone has high implied demand uncertainty. It will likely have a high margin, inaccurate demand forecasts, high stockout rates (if it is successful), and large markdowns (if it is a failure). This, too, matches well with Table 2-2.

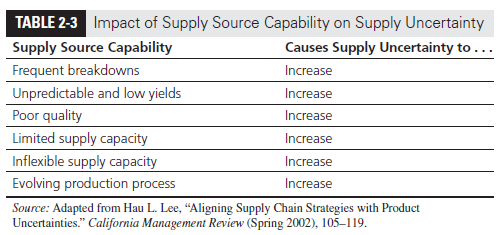

Lee (2002) pointed out that along with demand uncertainty, it is important to consider uncertainty resulting from the capability of the supply chain. For example, when a new component is introduced in the consumer electronics industry, the quality yields of the production process tend to be low and breakdowns are frequent. As a result, companies have difficulty delivering according to a well-defined schedule, resulting in high supply uncertainty for electronics manufacturers. As the production technology matures and yields improve, companies are able to follow a fixed delivery schedule, resulting in low supply uncertainty. Table 2-3 illustrates how various characteristics of supply sources affect the supply uncertainty.

Supply uncertainty is also strongly affected by the life-cycle position of the product. New products being introduced have higher supply uncertainty because designs and production processes are still evolving. In contrast, mature products have less supply uncertainty.

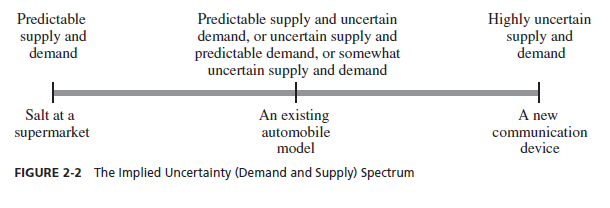

We can create a spectrum of uncertainty by combining the demand and supply uncertainty. This implied uncertainty spectrum is shown in Figure 2-2.

A company introducing a brand-new cell phone based on entirely new components and technology faces high implied demand uncertainty and high supply uncertainty. As a result, the implied uncertainty faced by the supply chain is extremely high. In contrast, a supermarket selling salt faces low implied demand uncertainty and low levels of supply uncertainty, resulting in a low implied uncertainty. Many agricultural products, such as coffee, are examples of supply chains facing low levels of implied demand uncertainty but significant supply uncertainty based on weather. The supply chain thus faces an intermediate level of implied uncertainty.

STEP 2: UNDERSTANDING THE SUPPLY CHAIN CAPABILITIES

After understanding the uncertainty that the company faces, the next question is: How does the firm best meet demand in that uncertain environment? Creating strategic fit is all about designing a supply chain whose responsiveness aligns with the implied uncertainty it faces.

Predictable supply and uncertain demand, or uncertain supply and predictable demand, or somewhat uncertain supply and demand

We now categorize supply chains based on different characteristics that influence their responsiveness and efficiency.

First, we provide some definitions. Supply chain responsiveness includes a supply chain’s ability to do the following:

- Respond to wide ranges of quantities demanded

- Meet short lead times

- Handle a large variety of products

- Build highly innovative products

- Meet a high service level

- Handle supply uncertainty

These abilities are similar to many of the characteristics of demand and supply that led to high implied uncertainty. The more of these abilities a supply chain has, the more responsive it is.

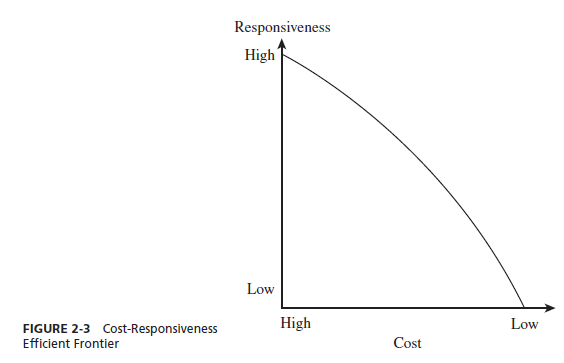

Responsiveness, however, comes at a cost. For instance, to respond to a wider range of quantities demanded, capacity must be increased, which increases costs. This increase in cost leads to the second definition: Supply chain efficiency is the inverse of the cost of making and delivering a product to the customer. Increases in cost lower efficiency. For every strategic choice to increase responsiveness, there are additional costs that lower efficiency.

The cost-responsiveness efficient frontier is the curve in Figure 2-3 showing the lowest possible cost for a given level of responsiveness. Lowest cost is defined based on existing technology; not every firm is able to operate on the efficient frontier, which represents the cost- responsiveness performance of the best supply chains. A firm that is not on the efficient frontier can improve both its responsiveness and its cost performance by moving toward the efficient frontier. In contrast, a firm on the efficient frontier can improve its responsiveness only by increasing cost and becoming less efficient. Such a firm must then make a trade-off between efficiency and responsiveness. Of course, firms on the efficient frontier are also continuously improving their processes and changing technology to shift the efficient frontier itself. Given the trade-off between cost and responsiveness, a key strategic choice for any supply chain is the level of responsiveness it seeks to provide.

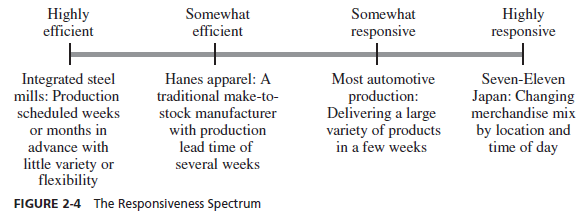

Supply chains range from those that focus solely on being responsive to those that focus on a goal of producing and supplying at the lowest possible cost. Figure 2-4 shows the responsiveness spectrum and where some supply chains fall on this spectrum.

The more capabilities constituting responsiveness a supply chain has, the more responsive it is. Seven-Eleven Japan replenishes its stores with breakfast items in the morning, lunch items in the afternoon, and dinner items at night. As a result, the available product variety changes by time of day. Seven-Eleven responds quickly to orders, with store managers placing replenishment orders less than 12 hours before they are supplied. This practice makes the Seven-Eleven supply chain very responsive. Another example of a responsive supply chain is W.W. Grainger. The company faces both demand and supply uncertainty; therefore, the supply chain has been designed to deal effectively with both to provide customers with a wide variety of MRO products within 24 hours. An efficient supply chain, in contrast, lowers cost by eliminating some of its responsive capabilities. For example, Sam’s Club sells a limited variety of products in large package sizes. The supply chain is capable of low costs, and the focus of this supply chain is clearly on efficiency.

STEP 3: ACHIEVING STRATEGIC FIT

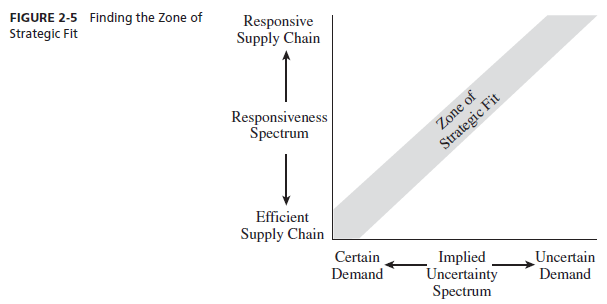

After mapping the level of implied uncertainty and understanding the supply chain position on the responsiveness spectrum, the third and final step is to ensure that the degree of supply chain responsiveness is consistent with the implied uncertainty. The goal is to target high responsiveness for a supply chain facing high implied uncertainty, and efficiency for a supply chain facing low implied uncertainty.

For example, the competitive strategy of McMaster-Carr targets customers that value having a large variety of MRO products delivered to them within 24 hours. Given the large variety of products and rapid desired delivery, demand from McMaster-Carr customers can be characterized as having high implied demand uncertainty. If McMaster-Carr designed an efficient supply chain, it may carry less inventory and maintain a level load on the warehouse to lower picking and packing costs. These choices, however, would make it difficult for the company to support the customer’s desire for a wide variety of products that are delivered within 24 hours. To serve its customers effectively, McMaster-Carr carries a high level of inventory and picking and packing capacity. Clearly, a responsive supply chain is better suited to meet the needs of customers targeted by McMaster-Carr even if it results in higher costs.

Now, consider a pasta manufacturer such as Barilla. Pasta is a product with relatively stable customer demand, giving it a low implied demand uncertainty. Supply is also quite predictable. Barilla could design a highly responsive supply chain in which pasta is custom made in small batches in response to customer orders and shipped via a rapid transportation mode such as FedEx. This choice would obviously make the pasta prohibitively expensive, resulting in a loss of customers. Barilla, therefore, is in a much better position if it designs a more efficient supply chain with a focus on cost reduction.

From the preceding discussion, it follows that increasing implied uncertainty from customers and supply sources is best served by increasing responsiveness from the supply chain. This relationship is represented by the “zone of strategic fit” illustrated in Figure 2-5. For a high level of performance, companies should move their competitive strategy (and resulting implied uncertainty) and supply chain strategy (and resulting responsiveness) toward the zone of strategic fit.

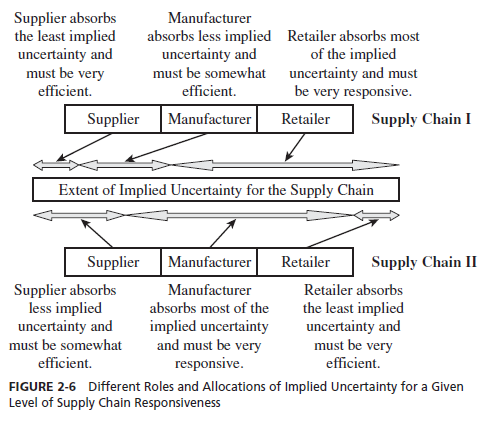

The next step in achieving strategic fit is to assign roles to different stages of the supply chain that ensure the appropriate level of responsiveness. It is important to understand that the desired level of responsiveness required across the supply chain may be attained by assigning different levels of responsiveness and efficiency to each stage of the supply chain as illustrated by the following examples.

IKEA is a Swedish furniture retailer with large stores in more than forty countries. IKEA has targeted customers who want stylish furniture at a reasonable cost. The company limits the variety of styles that it sells through modular design. The large scale of each store and the limited variety of furniture (through modular design) decrease the implied uncertainty faced by the supply chain. IKEA stocks all styles in inventory and serves customers from stock. Thus, it uses inventory to absorb all the uncertainty faced by the supply chain. The presence of inventory at large IKEA stores allows replenishment orders to its manufacturers to be more stable and predictable. As a result, IKEA passes along little uncertainty to its manufacturers, who tend to be located in low-cost countries and focus on efficiency. IKEA provides responsiveness in the supply chain, with the stores absorbing most of the uncertainty and being responsive, and the suppliers absorbing little uncertainty and being efficient.

In contrast, another approach for responsiveness may involve the retailer holding little inventory. In this case, the retailer does not contribute significantly to supply chain responsiveness, and most of the implied demand uncertainty is passed on to the manufacturer. For the supply chain to be responsive, the manufacturer now needs to be flexible and have low response times. An example of this approach is England, Inc., a furniture manufacturer located in Tennessee. Every week, the company makes several thousand sofas and chairs to order, delivering them to furniture stores across the country within three weeks. England, Inc.’s retailers allow customers to select from a wide variety of styles and promise relatively quick delivery. This imposes a high level of implied uncertainty on the supply chain. The retailers, however, do not carry much inventory and pass most of the implied uncertainty on to England, Inc. The retailers can thus be efficient because most of the implied uncertainty for the supply chain is absorbed by England, Inc., with its flexible manufacturing process. England, Inc., itself has a choice of how much uncertainty it passes along to its suppliers. By holding more raw material inventories, the company allows its suppliers to focus on efficiency. If it decreases its raw material inventories, its suppliers must become more responsive.

The preceding discussion illustrates that the supply chain can achieve a given level of responsiveness by adjusting the role of each of its stages. Making one stage more responsive allows other stages to focus on becoming more efficient. The best combination of roles depends on the efficiency and flexibility available at each stage. The notion of achieving a given level of responsiveness by assigning different roles and levels of uncertainty to different stages of the supply chain is illustrated in Figure 2-6. The figure shows two supply chains that face the same implied uncertainty but achieve the desired level of responsiveness with different allocations of uncertainty and responsiveness across the supply chain. Supply Chain I has a very responsive retailer that absorbs most of the uncertainty, allowing (actually requiring) the manufacturer and supplier to be efficient. Supply Chain II, in contrast, has a very responsive manufacturer that absorbs most of the uncertainty, thus allowing the other stages to focus on efficiency.

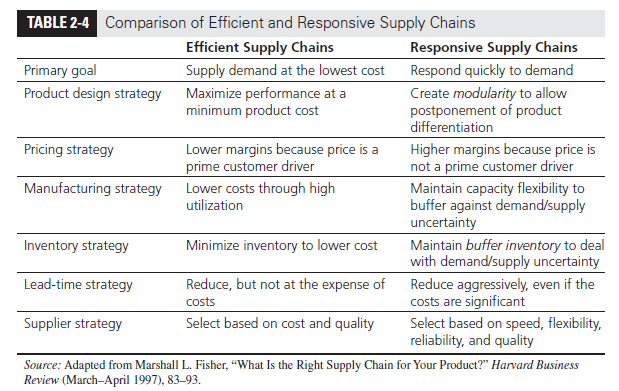

To achieve complete strategic fit, a firm must also ensure that all its functions maintain consistent strategies that support the competitive strategy. All functional strategies must support the goals of the competitive strategy. All substrategies within the supply chain—such as manufacturing, inventory, and purchasing—must also be consistent with the supply chain’s level of responsiveness. Table 2-4 lists some of the major differences in functional strategy between supply chains that are efficient and those that are responsive.

2. Tailoring the Supply Chain for Strategic Fit

Our previous discussion focused on achieving strategic fit when a firm serves a single market segment and the result is a well-defined and narrow strategic position. Although such a scenario holds for firms like IKEA, many firms are required to achieve strategic fit while serving many customer segments with a variety of products across multiple channels. In such a scenario, a “one size fits all” supply chain cannot provide strategic fit, and a tailored supply chain strategy is required. For example, Zara sells trendy items with unpredictable demand along with basics, such as white T-shirts, with a more predictable demand. Whereas Zara uses a responsive supply chain with production in Europe for trendy items, it uses a more efficient supply chain with production in Asia for the basics. This tailored supply chain strategy provides a better strategic fit for Zara compared with using a single supply chain. Another example is Levi Strauss, which sells both customized and standard-sized jeans. Demand for standard-sized jeans has a much lower demand uncertainty than demand for customized jeans. As a result, Levi Strauss must tailor its supply chain to meet both sets of needs.

In each of the previous examples, the products sold and the customer segments served have different implied demand uncertainty. When devising supply chain strategy in these cases, the key issue for a company is to design a tailored supply chain that is able to be efficient when implied uncertainty is low and responsive when it is high. By tailoring its supply chain, a company can provide responsiveness to fast-growing products, customer segments, and channels while maintaining low cost for mature, stable products and customer segments.

Tailoring the supply chain requires sharing operations for some links in the supply chain, while having separate operations for other links. The links are shared to achieve maximum possible efficiency while providing the appropriate level of responsiveness to each segment. For instance, all products may be made on the same line in a plant, but products requiring a high level of responsiveness may be shipped using a fast mode of transportation, such as FedEx. Products that do not have high responsiveness needs may be sent by slower and less expensive means such as truck, rail, or even ship. In other instances, products requiring high responsiveness may be manufactured using a flexible process, whereas products requiring less responsiveness may be manufactured using a less responsive but more efficient process. The mode of transportation used in both cases, however, may be the same. In other cases, some products may be held at regional warehouses close to the customer, whereas others may be held in a centralized warehouse far from the customer. W.W. Grainger holds fast-moving items with low implied uncertainty in its decentralized locations close to the customer. It holds slow-moving items with higher implied demand uncertainty in a centralized warehouse. Appropriate tailoring of the supply chain helps a firm achieve varying levels of responsiveness for a low overall cost. The level of responsiveness is tailored to each product, channel, or customer segment. Tailoring of the supply chain is an important concept that we develop further in subsequent chapters.

The concept of tailoring to achieve strategic fit is important in industries such as high-tech and pharmaceuticals, in which innovation is critical and products move through a life cycle. Let us consider changes in demand and supply characteristics over the life cycle of a product. Toward the beginning stages of a product’s life cycle:

- Demand is very uncertain, and supply may be unpredictable.

- Margins are often high, and time is crucial to gaining sales.

- Product availability is crucial to capturing the market.

- Cost is often a secondary consideration.

Consider a pharmaceutical firm introducing a new drug. Initial demand for the drug is highly uncertain, margins are typically high, and product availability is the key to capturing market share. The introductory phase of a product’s life cycle corresponds to high implied uncertainty, given the high demand uncertainty and the need for a high level of product availability. In such a situation, responsiveness is the most important characteristic of the supply chain.

As the product becomes a commodity product later in its life cycle, the demand and supply characteristics change. At this stage, it is typically the case that:

- Demand has become more certain, and supply is predictable.

- Margins are lower as a result of an increase in competitive pressure.

- Price becomes a significant factor in customer choice.

In the case of a pharmaceutical company, these changes occur when demand for the drug stabilizes, production technologies are well developed, and supply is predictable. This stage corresponds to a low level of implied uncertainty. As a result, the supply chain must change. In such a situation, efficiency becomes the most important characteristic of the supply chain. The pharmaceutical industry has reacted by building a mix of flexible and efficient capacity whose use is tailored to the product life cycle. New products are typically introduced using flexible capacity that is more expensive but responsive enough to deal with the high level of uncertainty during the early stages of the life cycle. Mature products with high demand are shifted to dedicated capacity that is highly efficient because it handles low levels of uncertainty and enjoys the advantage of high scale. The tailored capacity strategy has allowed pharmaceutical firms to maintain strategic fit for a wide range of products at different stages of their life cycle.

In the next section, we describe how the scope of the supply chain has expanded when achieving strategic fit. We also discuss why expanding the scope of strategic fit is critical to supply chain success.

Source: Chopra Sunil, Meindl Peter (2014), Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation, Pearson; 6th edition.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!