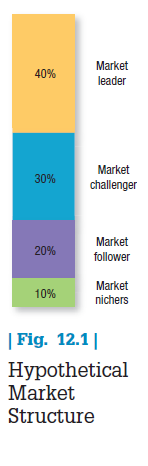

Suppose a market is occupied by the firms shown in Figure 12.1. Forty percent is in the hands of a market leader, another 30 percent belongs to a market challenger, and 20 percent is claimed by a market follower willing to maintain its share and not rock the boat. Market nichers, serving small segments larger firms don’t reach, hold the remaining 10 percent. Sometimes growth depends on adopting the right competitive strategies.

A market leader has the largest market share and usually leads in price changes, new-product introductions, distribution coverage, and promotional intensity. Some historical market leaders are Microsoft (computer software), Gatorade (sports drinks), Best Buy (retail electronics), McDonald’s (fast food), BlueCross BlueShield (health insurance), and Visa (credit cards).

Although marketers assume well-known brands are distinctive in consumers’ minds, unless a dominant firm enjoys a legal monopoly, it must maintain constant vigilance. A powerful product innovation may come along, a competitor might find a fresh marketing angle or commit to a major marketing investment, or the leader’s cost structure might spiral upward. One well-known brand and market leader that has worked hard to stay on top is Xerox.10

XEROX Xerox has had to become much more than just a copier company. Now a blue-chip icon with the name that became a verb, the company sports the broadest array of imaging products in the world and dominates the market for high-end printing systems while also offering a new range of printing and business-related services. It has made a product line transition from the old light lens technology to digital systems and is finding ways to make color copying less expensive and even to print in 3-D. Xerox provides broader document and print-manager services to help companies lower costs by eliminating desktop printers, reducing paper use, and installing multifunction multiuser devices that are more efficient, break down less, and use cheaper supplies. Under CEO Ursula Burns, the firm is becoming more of a services company, providing bill processing, business processing, and IT outsourcing. A $6.4 billion acquisition of Affiliated Computer Services (ACS) allowed Xerox to plunge its technology into back-office operations. A call to Virgin America customer care, a paper or online submission of a health insurance claim, and a query to solve a smart phone problem all might be handled by a Xerox employee. A new Xerox device—a compact computer with scanning, printing, and Internet capabilities—allows ACS insurance agents in the field to scan claims onsite to be sorted, routed, and put immediately into a workflow system. Xerox is embracing technology in its marketing too. The company’s “Information Overload” campaign employed a personalized video, e-mail campaign, and direct mail piece. Each customer received a personalized URL (PURL) based on his or her behavior and interests, leading to click-through rates of 35 percent to 40 percent as opposed to the typical 1 percent to 2 percent industry rates. A new print and TV ad campaign, “Simplicity by the Numbers,” acknowledges the brand’s heritage while highlighting its new capabilities. One TV ad opened with a women standing in front of a copier saying, “When I say Xerox, I know what you’re thinking,” After printing the image of a transit map, she states, “Transit fares, as in the 37 billion transit fares we help collect each year.”

To stay number one, the firm must first find ways to expand total market demand. Second, it must protect its current share through good defensive and offensive actions. Third, it should increase market share, even if market size remains constant. Let’s look at each strategy.

1. EXPANDING TOTAL MARKET DEMAND

When the total market expands, the dominant firm usually gains the most. If Heinz can convince more people to use ketchup, or to use ketchup with more meals, or to use more ketchup on each occasion, the firm will benefit considerably because it already sells almost two-thirds of the country’s ketchup. In general, the market leader should look for new customers or more usage from existing customers.

NEW CUSTOMERS As Chapter 2 suggested, a company can search for new users among three groups: those who might use it but do not (market-penetration strategy), those who have never used it (new-market segment strategy), or those who live elsewhere (geographical-expansion strategy). Here is how Starbucks has described its multipronged approach to growth on its corporate Web site.11

Starbucks purchases and roasts high-quality whole bean coffees and sells them along with fresh, rich- brewed, Italian style espresso beverages, a variety of pastries and confections, and coffee-related accessories and equipment—primarily through its company-operated retail stores. In addition to sales through our company-operated retail stores, Starbucks sells whole bean coffees through a specialty sales group and supermarkets. Additionally, Starbucks produces and sells bottled Frappuccino® coffee drinks and a line of premium ice creams through its joint venture partnerships and offers a line of innovative premium teas produced by its wholly owned subsidiary, Tazo Tea Company. The Company’s objective is to establish Starbucks as the most recognized and respected brand in the world.

In targeting new customers, the firm should not lose sight of existing ones. Daimler, maker of Mercedes-Benz, has developed a balanced approach to capitalize on both the established demand from mature markets in the European Union, United States, and Japan and the enormous potential offered by fast-growing emerging markets. As the company’s chairman Dieter Zetsche proclaimed, “You cannot do either/or. You have to maintain your strength in traditional markets and even expand it.”12

MORE USAGE Marketers can try to increase the amount, level, or frequency of consumption. They can sometimes boost the amount through packaging or product redesign. Larger package sizes increase the amount of product consumers use at one time.13 Consumers use more of impulse products such as soft drinks and snacks when the product is made more available.

Ironically, some food firms such as Hershey’s have developed smaller packaging sizes that have actually increased sales volume through more frequent usage.14 In general, increasing frequency of consumption requires either (1) identifying additional opportunities to use the brand in the same basic way or (2) identifying completely new and different ways to use the brand.

Additional Opportunities to Use the Brand A marketing program can communicate the appropriateness and advantages of using the brand. Pepto-Bismol stomach remedies are in 40 percent of U.S. households, but only 7 percent of people claim to have used them in the previous 12 months. To expand usage and make the brand more top of mind, a holiday campaign linked it to party festivities and celebrations with the tag line “Eat, Drink, and Be Covered.” In a somewhat similar vein, on the inside of the front flap of its package, Orbit chewing gum puts the message, “Eat. Drink. Chew. A Good Clean Feeling.” to reinforce that the brand can be a substitute for brushing teeth.15

Another opportunity arises when consumers’ perceptions of their usage differs from reality. Consumers may fail to replace a short-lived product when they should because they overestimate how long it stays fresh or operates effectively.16 One strategy is to tie the act of replacing the product to a holiday, event, or time of year. Marketers of household products such as batteries for alarms and filters for vacuum cleaners, furnaces, and air conditioners use the beginning and end of Daylight Savings Time twice a year as a means to remind consumers.

Another approach might be to provide consumers with (1) better information about when they first used the product or need to replace it or (2) a gauge of the current level of product performance. Gillette razor cartridges feature colored stripes that slowly fade with repeated use, signaling the user to move on to the next cartridge. Marketers for Monroe shock absorbers and struts launched the clever, fully integrated “Everything Gets Old. Even Your Shocks” campaign, which drew comparisons between worn shocks and struts and familiar consumer items that eventually wear out and need to be replaced such as shoes, socks, tires, and even bananas!17

New Ways to Use the Brand The second approach to increasing frequency of consumption is to identify completely new and different applications. Food product companies have long advertised recipes that use their branded products in different ways. After discovering that some consumers used Arm & Hammer baking soda as a refrigerator deodorant, the company launched a heavy promotion campaign focusing on this use and succeeded in getting half the homes in the United States to adopt it. Next, the company expanded the brand into a variety of new product categories such as toothpaste, antiperspirant, and laundry detergent.

2. PROTECTING MARKET SHARE

While trying to expand total market size, the dominant firm must actively defend its current business: Boeing against Airbus, Staples against Office Depot, and Google against Yahoo! and Microsoft.18 How can the leader do so? The most constructive response is continuous innovation. The front-runner should lead the industry in developing new products and customer services, distribution effectiveness, and cost cutting. Comprehensive solutions increase competitive strength and value to customers so they feel appreciative or even privileged to be a customer as opposed to feeling trapped or taken advantage of.19

PROACTIVE MARKETING In satisfying customer needs, we can draw a distinction between responsive marketing, anticipative marketing, and creative marketing. A responsive marketer finds a stated need and fills it. An anticipative marketer looks ahead to needs customers may have in the near future. A creative marketer discovers solutions customers did not ask for but to which they enthusiastically respond. Creative marketers are proactive market-driving firms, not just market-driven ones.20

Many companies assume their job is simply to adapt to customer needs. They are reactive mostly because they are overly faithful to the customer-orientation paradigm and fall victim to the “tyranny of the served market.” Successful companies instead proactively shape the market to their own interests. Instead of trying to be the best player, they change the rules of the game.21

A company needs two proactive skills: (1) responsive anticipation to see the writing on the wall, as when IBM changed from a hardware producer to a service business, and (2) creative anticipation to devise innovative solutions. Note that responsive anticipation is performed before a given change, while reactive response happens after the change takes place. Accenture maintains that 10 consumer trends covering areas like e-commerce, social media, and a desire to express individuality will yield market opportunities worth more than $2 trillion between 2013 and 2016.22 Proactive companies will reap the most benefit from those shifts.

Proactive companies create new offers to serve unmet—and maybe even unknown—consumer needs. In the late 1970s, Akio Morita, the Sony founder, was working on a pet project that would revolutionize the way people listened to music: a portable cassette player he called the Walkman. Engineers at the company insisted there was little demand for such a product, but Morita refused to part with his vision. By the 20th anniversary of the Walkman, Sony had sold more than 250 million in nearly 100 different models.23

Proactive companies may redesign relationships within an industry, like Toyota did with its relationship to its suppliers. Or they may educate and engage customers, as lululemon does with yoga and workouts.24

LULULEMON While attending yoga classes, Canadian entrepreneur Chip Wilson decided the cotton- polyester blends most fellow students wore were too uncomfortable. After designing a well-fitting, sweat-resistant black garment to sell, he also decided to open a yoga studio, and lululemon was born. The company has taken a grassroots approach to growth that creates a strong emotional connection with its customers. Before it opens a store in a new city, it first identifies influential yoga instructors or other fitness teachers. In exchange for a year’s worth of clothing, these yogi serve as “ambassadors,” hosting students at lululemon-sponsored classes and product sales events. They also provide product design advice to the company. The cult-like devotion of lululemon’s customers is evident in their willingness to pay $92 for a pair of workout pants that might cost only $60 to $70 from Nike or Under Armour. lululemon can sell as much as $1,800 worth of product per square feet in its approximately 100 stores, three times what established retailers Abercrombie & Fitch and J.Crew sell. Although the company has encountered some challenges with inventory management issues, production snafus, and negative publicity surrounding statements by its founder, it is still looking to expand beyond yoga-inspired athletic apparel and accessories into similar products in other sports such as running, swimming, and biking.

Companies need to practice “uncertainty management.” Proactive firms:

- are ready to take risks and make mistakes,

- have a vision of the future and of investing in it,

- have the capabilities to innovate,

- are flexible and non-bureaucratic, and

- have many managers who think proactively.

Companies that are too risk-averse won’t be winners.

DEFENSIVE MARKETING Even when it does not launch offensives, the market leader must not leave any major flanks exposed. The aim of defensive strategy is to reduce the probability of attack, divert attacks to less- threatened areas, and lessen their intensity. A leader would like to do anything it legally and ethically can to reduce competitors’ ability to launch a new product, secure distribution, and gain consumer awareness, trial, and repeat.25 In any strategy, speed of response can make an important difference to profit.

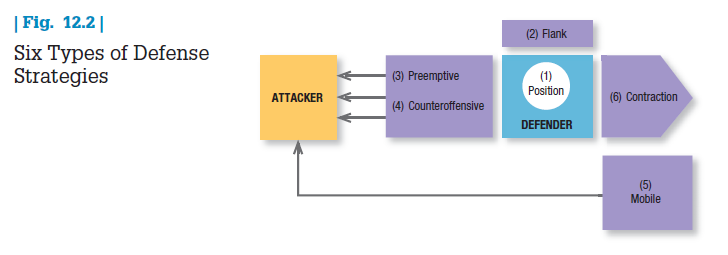

A dominant firm can use the six defense strategies summarized in Figure 12.2.26 Decisions about which strategy to adopt will depend in part on the company’s resources and goals and its expectations about how competitors will react.

Position defense. Position defense means occupying the most desirable position in consumers’ minds, making the brand almost impregnable. Procter & Gamble “owns” the key functional benefit in many product categories, with Tide detergent for cleaning, Crest toothpaste for cavity prevention, and Pampers diapers for dryness.

- Flank defense. The market leader should erect outposts to protect a weak front or support a possible counterattack. Procter & Gamble brands such as Gain and Cheer laundry detergent and Luvs diapers have played strategic offensive and defensive roles in support of the Tide and Pampers brands, respectively.

- Preemptive defense. A more aggressive maneuver is to attack first, perhaps with guerrilla action across the market—hitting one competitor here, another there—and keeping everyone off balance. Another is to achieve broad market envelopment that signals competitors not to attack.28 Bank of America’s 16,220 ATMs and 5,858 retail branches nationwide provide steep competition to local and regional banks.29 Yet another preemptive defense is to introduce a stream of new products and announce them in advance, signaling competitors that they will need to fight to gain market share. If Microsoft announces plans for a new-product development, smaller firms may concentrate their development efforts in other directions to avoid head-to-head competition. Some high-tech firms have been accused of selling “vaporware”—announcing products that miss delivery dates or are never introduced.30

- Counteroffensive defense. In a counteroffensive, the market leader can meet the attacker frontally and hit its flank or launch a pincer movement so the attacker will have to pull back to defend itself. Another form of counteroffensive is the exercise of economic or political clout. The leader may try to crush a competitor by subsidizing lower prices for a vulnerable product with revenue from its more profitable products, or it may prematurely announce a product upgrade to prevent customers from buying the competitor’s product. Or the leader may lobby legislators to take political action to inhibit the competition or initiate appropriate legal actions. Tech leaders like Apple, Intel, and Microsoft have aggressively defended their brands in court.

- Mobile defense. In mobile defense, the leader stretches its domain over new territories through market broadening and market diversification. Market broadening shifts the company’s focus from the current product to the underlying generic need. Thus, “petroleum” companies such as BP sought to recast themselves as “energy” companies. This change required them to research the oil, coal, nuclear, hydroelectric, and chemical industries. Market diversification shifts the company’s focus into unrelated industries. When U.S. tobacco companies such as Reynolds and Philip Morris acknowledged the growing curbs on cigarette smoking, instead of defending their market position or looking for cigarette substitutes, they moved quickly into new industries such as beer, liquor, soft drinks, and frozen foods.

- Contraction defense. Sometimes large companies can no longer defend all their territory. In planned contraction (also called strategic withdrawal), they give up weaker markets and reassign resources to stronger ones. Beginning in 2006, Sara Lee sold off products that accounted for a large percentage of its revenues—including its strong Hanes hosiery brand and global body care and European detergents businesses. In 2012, it split its remaining products into two businesses. Hillshire Brands became the new name of the company, which focused on its core Hillshire Farms packaged meats business in North America, and D.E. Master Blenders 1753 was a spin-off company for its successful European coffee-and-tea business.31

P&G sold Pringles to Kellogg for almost $2.7 billion in an all-cash transaction when it decided it wanted to get out of the foods business to focus on its core household and consumer products.32 Another company that restructured its business to improve competitiveness was Kraft.33

KRAFT After years of acquisitions, CEO Irene Rosenfeld announced in 2011 that Kraft would split into two businesses by the end of 2012: A fast-growing global snacks and candy business to include Oreo cookies and Cadbury candy and a slower-growing North American grocery business with long-terms stalwarts Maxwell House coffee, Planters peanuts, Kraft cheese, and Jell-O. The rationale was to improve performance and give investors distinctly different choices. The snacks and candy business was branded as Mondelez International and was positioned as a high-growth company with many opportunities in emerging markets such as China and India. Coined by two employees, Mondelez is a mash-up of the words for “world” and “delicious” in Latin and several other Romance languages. The grocery business retained the Kraft Foods name, and because it consisted of many category-dominant meat and cheese brands, it was seen as more of a cash cow for investors interested in consistent dividends. Mondelez has ramped up for rapid expansion, while Kraft Foods has focused on cost-cutting and selective investment behind its power brands.

3. INCREASING MARKET SHARE

No wonder competition has turned fierce in so many markets: One share point can be worth tens of millions of dollars. Gaining increased share does not automatically produce higher profits, however—especially for laborintensive service companies that may not experience many economies of scale. Much depends on the company’s strategy.34

Because the cost of buying higher market share through acquisition may far exceed its revenue value, a company should consider four factors first:

- The possibility of provoking antitrust action. Frustrated competitors are likely to cry “monopoly” and seek legal action if a dominant firm makes further inroads. Microsoft and Intel have had to fend off numerous lawsuits and legal challenges around the world as a result of what some feel are inappropriate or illegal business practices and abuse of market power.

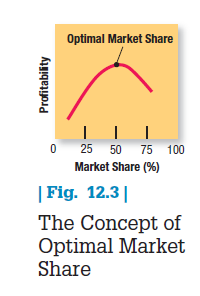

- Economic cost. Figure 12.3 shows that profitability might fall with market share gains after some level. In the illustration, the firm’s optimal market share is 50 percent. The cost of gaining further market share might exceed the value if holdout customers dislike the company, are loyal to competitors, have unique needs, or prefer dealing with smaller firms. And the costs of legal work, public relations, and lobbying rise with market share. Pushing for higher share is less justifiable when there are unattractive market segments, buyers who want multiple sources of supply, high exit barriers, and few scale or experience economies. Some market leaders have even increased profitability by selectively decreasing market share in weaker areas.35

- The danger of pursuing the wrong marketing activities. Companies successfully gaining share typically outperform competitors in three areas: new-product activity, relative product quality, and marketing expenditures.36 Companies that attempt to increase market share by cutting prices more deeply than competitors typically don’t achieve significant gains because rivals meet the price cuts or offer other values so buyers don’t switch.

- The effect of increased market share on actual and perceived quality. Too many customers can put a strain on the firm’s resources, hurting product value and service delivery. Charlotte-based FairPoint Communications struggled to integrate the 1.3 million customers it gained in buying Verizon Communications’s New England franchise. A slow conversion and significant service problems led to customer dissatisfaction, regulator’s anger, and eventually short-term bankruptcy.37

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

19 May 2021

19 May 2021

20 May 2021

19 May 2021

20 May 2021

19 May 2021