1. Definition and Overview

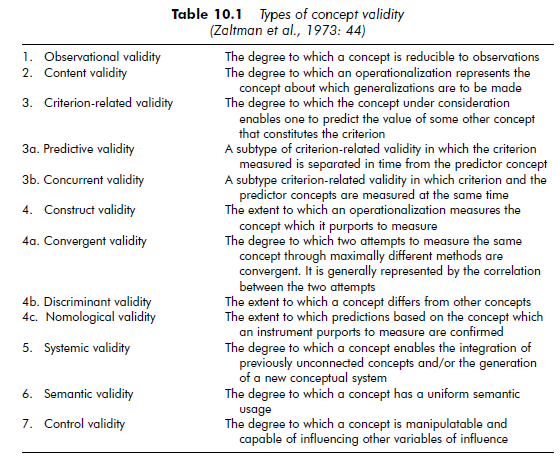

The concept of construct validity is peculiar to the social sciences, where research often draws on one or several abstract concepts that are not always directly observable (Zaltman et al., 1973). These can include change, performance, or power. Concepts are the building blocks of propositions and theories used to describe, explain or predict organizational phenomena. As they are abstract forms that generally have several different meanings, it is often difficult to find rules to delimit them. Because of this it is important that the researcher’s principal concern is the need to establish a common understanding of the concepts used. This poses the question of the validity of these concepts, and in the following discussion and in Table 10.1 we present several different approaches to concept validity (Zaltman et al., 1973).

Among the different types of validity, those most often used are criterion- related validity content validity and construct validity. However, as Carmines and Zeller (1990) emphasize, criterion validation procedures cannot be applied to all of the abstract concepts used in the social sciences. Often no relevant criterion exists with which to assess a measure of a concept. (For example while the meter-standard forms a reference criterion for assessing distance, there is no universal criterion for assessing a measure of organizational change). In the same way, content validity assumes we can delimit the domain covered by a concept. For example, the concept ‘arithmetical calculation’ incorporates addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. But what is covered by concepts such as organizational change or strategic groups? Content validity is therefore quite difficult to apply in the social sciences (Carmines and Zeller, 1990). As pointed out by Cronbach and Meehl (1955: 282),1 it seems that only construct validity is really relevant in social sciences: ‘construct validity must be investigated whenever no criterion on the universe of content is accepted as entirely adequate to define the quality to be measured’.

One of the main difficulties in assessing construct validity in management research lies in the process of operationalization. Concepts are reduced to a series of operationalization or measurement variables. For example, the concept ‘organizational size’ can be operationalized through the variables turnover, number of employees or total assets. Such variables are observable or measurable indicators of a concept that is often not directly observable. We call this operationalized concept the ‘construct’ of the research. When we address construct validity, we do not attempt to examine the process of constructing the research question, but the process of operationalizing it. Research results are not measures of the theoretical concept itself, but measures of the construct – the concept as it is put into operation. In questioning the validity of the construct we must ensure that the operationalized concept expresses the theoretical concept.

2. Assessing Construct Validity

2.1. Quantitative research

Testing construct validity in a quantitative research project consists most often in determining whether the variables used to measure the phenomenon being studied are a good representation of it.

To achieve this, researchers need to ensure that different variables used to measure the same phenomenon correlate strongly with each other (‘convergent validity’) and that variables used to measure different phenomena are not perfectly correlated (‘discriminant validity’). In other words, testing construct validity comes down to confirming that variables measuring the same concept converge, and differ from variables that measure different concepts. To measure the correlation between items, researchers can use Campbell and Fiske’s (1959) multitrait-multimethod matrix.

The researcher can equally well turn to other statistical data-processing tools. In particular, factor analysis can be used to measure the degree of construct validity (Carmines and Zeller, 1990).

2.2. Qualitative research

For qualitative research we need to establish that the variables used to operationalize the studied concepts are appropriate. We also need to evaluate the degree to which our research methodology (both the research design and the instruments used for collecting and analysing data) enables us to answer the research question. It is therefore essential, before collecting data, to ensure that the unit of analysis and the type of measure chosen will enable us to obtain the necessary information: we must define what is to be observed, how and why.

We must then clearly establish the initial research question, which will guide our observations in the field. Once this has been done, it is then essential to define the central concepts, which more often than not are the dimensions to be measured. For example, in order to study organizational memory, Girod- Seville (1996) first set out to define its content and its mediums. She defined it as the changeable body of organizational knowledge (which is eroded and enhanced over time) an organization has at its disposal, and also clearly defined each term of her definition.

The next step consists of setting out, on the basis of both the research question and existing literature, a conceptual framework through which the various elements involved can be identified. This framework provides the basis on which to construct a methodology, and enables the researcher to determine the characteristics of the observational field and the units of the analysis. The conceptual framework describes, most often in a graphic form, the main dimensions to be studied, the key variables and the relationships which are assumed to exist between these variables. It specifies what is to be studied, and through this determines the data that is to be collected and analyzed.

The researcher should show that the methodology used to study the research question really does measure the dimensions specified in the conceptual framework. To this end, writers such as Yin (1989) or Miles and Huberman (1984a) propose the following methods to improve the construct validity of qualitative research:

- Use a number of different sources of data.

- Establish a ‘chain of evidence’ linking clues and evidence that confirm an observed result. This should enable any person outside the project to follow exactly how the data has directed the process, leading from the formulation of the research question to the statement of the conclusions.

- Have the case study verified by key actors.

Example: Strategies used in qualitative research to improve construct validity (Miles and Huberman, 1984a; Yin, 1989)

Multiple data-sources: interviews (open, semi-directive, to correlate or to validate), documentation (internal documents, union data, internal publications, press articles, administrative records, etc.), the researcher’s presence in the field (obtaining additional information about the environment, the mood in the workplace, seeing working conditions firsthand, observing rituals such as the coffee-break, informal meetings, etc.).

Having key informants read over the case study: this includes those in charge of the organizational unit being studied, managers of other organizational units, managers of consultant services that operate within the organization.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021