A sales contest is a special selling campaign offering incentives in the form of prizes or awards beyond those in the compensation plan. The underlying purpose of all sales contests is to provide extra incentives to increase sales volume, to bring in more profitable sales volume, or to do both. In line with Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory, sales contests aim to fulfill individual needs for achievement and recognition—both motivational factors. In terms of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, sales contests aim to fulfill individual needs for esteem and self-actualization— both higher-order needs. In addition, sales contests develop team spirit, boost morale (by making jobs more interesting), and make personalselling efforts more productive.

1. Specific Objectives

Sales contests are aimed to accomplish specific objectives, generally one per contest, within limited periods of time. Most sales contests aim to motivate sales personnel:

- To obtain new customers.

- To secure larger orders per sales call.

- To push slow-moving items, high-margin goods, or new products.

- To overcome a seasonal sales slump.

- To sell a more profitable mix of products.

- To improve the performance of distributors’ sales personnel.

- To promote seasonal merchandise.

- To obtain more product displays by dealers.

- To get reorders.

- To promote special deals to distributors, dealers, or both.

2. Contest Formats

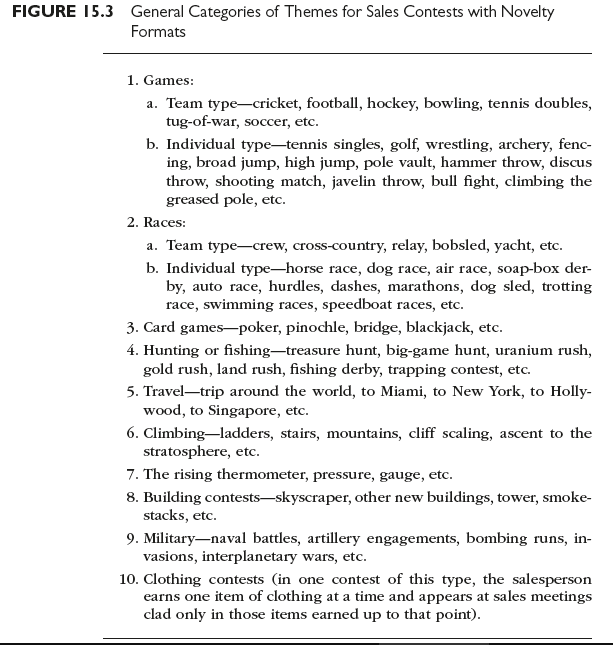

Contest formats are classified as direct or novelty. A direct format has a contest theme describing the specific objective, such as obtaining new accounts—for example, “Let’s go after new customers.”- A novelty format uses a theme which focuses upon a current event, sport, or the like, as in “Let’s hunt for hidden treasure” (find new customers) or “Let’s start panning gold” (sell more profitable orders). Some executives say a novelty format makes a sales contest more interesting and more fun for the participants. Others say that novelty formats are insults to mature people.

A format should be timely, and its effectiveness is enhanced if it coincides with an activity in the news. The theme should bear an analogous relationship to the specific contest objective—for example, climbing successive steps on a ladder can be made analogous to different degrees of success, experienced at different times—in persuading dealers to permit the erection of product displays. Finally, the theme should lend itself to contest promotion. Hundreds of themes for novelty formats have been used, most falling into one or another of the ten general categories shown in Figure 15.3.

3. Contest Prizes

There are four kinds of contest prizes: cash, merchandise, travel, and special honors or privileges. Cash and merchandise are the most common prizes. Many sales contests feature more than one kind of prize, for example, travel for large awards and merchandise for lesser awards. Some contests give participants the option of accepting one prize rather than another.

Cash. The potency of cash as an incentive weakens as an individual’s unfulfilled needs are pushed farther up in the need hierarchy. Once basic physiological needs and safety and security needs are satisfied, whatever potency money retains as an incentive relates to unfulfilled esteem and achievement needs. Noncash prizes fill these needs better than cash.

If the compensation plan provides sales personnel with sufficient income to meet basic physiological needs and safety and security needs, a cash prize is a weak incentive unless it is a substantial sum—say, 10 to 25 percent of an individual’s regular annual income. A cash prize of $500 means little to most sales personnel, and they exert token efforts to win it. Another objection to cash prizes is that winners mix them with other income, and thus have no permanent evidence of their achievements.

Merchandise. Merchandise is superior to cash in several respects. Winners have permanent evidence of their achievement. The merchandise prize is obtained at wholesale, so it represents a value larger than the equivalent cash. For the same total outlay, too, more merchandise prizes than cash awards can be offered; hence, the contest can have more winners.

Merchandise prizes should be items desired by salespersons and their families. One way to sidestep this problem is to let winners select from a variety of offerings. From the psychological standpoint, people feel good when they are permitted to assert their individuality and take their choice. A number of “merchandise incentive agencies,” some of them providing a complete sales contest planning service, specialize in furnishing prizes. Agencies issue catalogs with prices stated in “points” rather than in money.

Travel. Travel awards are popular. Few things can be glamorized more effectively than a trip to a luxury resort or an exotic land. The lure of a “trip of a lifetime” is a strong incentive, especially for the person to “escape” the job’s routine. Travel awards generally provide trips for winners and their spouses, this being advisable both to obtain the spouse’s motivational support and to avoid the spouse’s opposition to solo vacation trips by the salesperson.

Special honors or privileges. This award has many forms: a letter from a top executive recognizing the winner’s superior performance, a loving cup, a special trip to a head office meeting, or membership in a special group or club that has certain privileges. These awards provide strong incentives, as, for example, they do with life insurance salespersons who push to gain membership in “the million-dollar club.”

The special honor or privilege award is used mainly by firms employing sales personnel who are almost “independent entrepreneurs.” Such awards, however, are appropriate wherever management desires to strengthen group identity and build team spirit. This type of award appeals to the salesperson’s belongingness and social relations needs, which, according to Maslow, an individual strives to satisfy after fulfilling basic physiological needs and safety and security needs. It also appeals to esteem and self-actualization needs (as do all other contest awards).

4. How Many Prizes and How Should They Be Awarded?

To stimulate widespread interest in the contest, it is a good idea to make it possible for everyone to win. This means that the basis for awards should be chosen with care. Contest planners recommend that present performance levels be taken into account—to motivate the average or inexperienced salesperson along with the star performer—and the basis of award be for improvement rather than total performance. Hence, total sales volume is less effective as an award basis than, for example, percent of quota achieved or percent of improvement in quota achievement. Many contests offer awards to all showing improvement, but the value of individual awards varies with the amount of improvement. The danger in offering only a few large prizes is that the motivational force will be restricted to the few who have a real chance of winning—the rest, knowing they have no chance to win, give up before they start.

5. Contest Duration

Contest duration is important in maintaining the interest of sales personnel. Contests run for periods as short as a week and as long as a year, but most run from one to four months. One executive claims that thirteen weeks (a calendar quarter) is ideal; another states that no contest should last longer than a month; still another points to a successful contest lasting six months. There are no set guides. Contest duration should be decided after considering the length of time interest and enthusiasm can be maintained, the period over which the theme can be kept timely, and the interval needed to accomplish the contest objective.

6. Contest Promotion

Effective contest promotion is important. To most sales personnel, a contest is nothing new. A clever theme and attractive prizes may arouse interest, but a planned barrage of promotional material develops enthusiasm. A teaser campaign sometimes precedes the formal contest announcement; at other times, the announcement comes as a dramatic surprise. As the contest progresses, other techniques hold and intensify interest. Results and standings are reported at sales meetings or by daily or weekly bulletins. The sales manager sends emails carrying news of important developments or changes in relative standings. At intervals, new or special prizes are announced.

Management encourages individuals or groups to compete against each other. Reports of standings are addressed to spouses. If the prizes selected arouse the spouses’ interest, continuing enthusiasm is generated in the home. The contest administrator should from time to time inject new life into the contest. From the start regular news flashes on comparative standings should be sent out, and, if initial contest incentives are not producing the desired results, the administrator adds the stimuli needed.

7. Managerial Evaluation of Contests

There are two times when management should evaluate a sales contest— before and after. Pre-evaluation aims to detect and correct weaknesses. Postevaluation seeks insights helpful in improving future contests. Both pre- and post-evaluations cover alternatives, short- and long-term effects, design, fairness, and impact upon sales force morale.

The contest versus alternatives. If serious defects exist in key aspects of sales force management, a sales contest is not likely to provide more than a temporary improvement. Deficiencies caused by bad recruiting, ineffective training, incompetent supervision, or an inappropriate compensation plan are not counterbalanced, even temporarily let alone permanently, by a sales contest. The underlying purpose of all sales contests is to provide extra incentives to increase sales volume, to bring in more profitable volume, or to do both—this purpose is not accomplished if sales force management has basic weaknesses. Other avenues to improvement of selling efficiency need exploring and evaluating at the time that a sales contest is being considered. Probable results of pursuing these other avenues are taken into account in contest planning and in the post mortem evaluation.

Short- and long-term effects. A sales contest accomplishes its purpose if it increases sales volume, brings in more profitable volume, or does both in the short and the long run. No contest is a real success if it borrows sales from preceding months, succeeding months, or both. Successful contests increase both contest period sales and long-run sales (although there may be a temporary sales decline after the contest is over) because they inculcate desirable selling patterns that personnel retain. Furthermore, successful contests so boost the spirits of sales personnel that there is a beneficial carryover effect.

Design. A well-designed contest provides motivation to achieve the underlying purpose, while increasing the gross margin earned on sales volume by at least enough to pay contest costs. The contest format, whether direct or novel, should tie in directly with the specific objectives, include easy-to- understand and fair contest rules, and lend itself readily to promotion.

Fairness. All sales personnel should feel that the contest format and rules give everyone a fair chance of winning the more attractive awards. While the contest is on, all sales personnel should continue to feel that they have real chances of winning something. A sales contest is unfair if its format causes some to give up before it starts and others to stop trying before it is over.

Impact upon sales force morale. Successful sales contests result in permanently higher levels of sales force morale. If the contest format causes personal rivalries, it may have the counterproductive effect of creating jealousy and antagonism among the sales force. Even if sales personnel compete for individual awards, it is often advisable to organize teams and place the emphasis on competition among teams for recognition rather than among individuals for personal gain.

8. Objections to Sales Contests

Only one in four sales departments use sales contests. Why? Among the standard objections are these:

- Salespeople are paid for their services under provisions of the basic compensation plan and there is no reason to reward them further for performing regular duties.

- High-caliber and more experienced sales personnel consider sales contests juvenile and silly.

- Contests lead to unanticipated and undesirable results, such as increased returns and adjustments, higher credit loss, and overstocking of dealers.

- Contests cause salespeople to bunch sales during the competition, and sales slumps occur both before and after the contest.

- The disappointment suffered by contest losers causes a general decline in sales force morale.

- Contests are temporary motivating devices and, if used too frequently, have a narcotic effect. No greater results in the aggregate are obtained with contests than without them.

- The competitive atmosphere generated by a sales contest weakens team spirit.

The first objection indicates misunderstanding of both personnel motivation and contest design, and the second may or may not be true in individual situations. All the other objections are overcome through good contest design, intelligent contest administration, and proper handling of other aspects of sales force management. Assuming that sales management is competent, thorough planning and effective administration of a contest can produce lasting benefits for both sales personnel and company. If a contest is used as a substitute for management, it is likely to have bad results.

Under some circumstances, nevertheless, sales contests are ill advised. When a firm’s products are in short supply, for instance, it is ridiculous to use a contest to stimulate orders, but the same firm might find a contest appropriate to lower selling expense or improve sales reports. Companies distributing industrial goods (that is, raw materials, fabricating materials and parts, installations, accessory equipment, and operating supplies) do not find sales contests effective for stimulating sales—except, of course, where it is possible to take sales away from competitors. But, again, industrial-goods companies use contests to reduce selling costs, improve salespeople’s reports, and improve customer service. Similarly, where the product is highly technical and is sold only after long negotiation, as with many industrial goods, sales contests for stimulating sales volume are inappropriate.

Source: Richard R. Still, Edward W. Cundliff, Normal A. P Govoni, Sandeep Puri (2017), Sales and Distribution Management: Decisions, Strategies, and Cases, Pearson; Sixth edition.

24 May 2021

25 May 2021

25 May 2021

25 May 2021

25 May 2021

24 May 2021