1. Who Is a “Customer”?

Webster defines a customer as “one that purchases a commodity or service.” This definition talks of an interface between the seller and the customer who are two different entities. Here, customers are beyond the bounds of an organization.

In the TQM perspective, a customer is anyone (organization) who receives and uses what an organization or individual provides. This definition offers an important dimension that customers are no longer just beyond the organization. Instead of being outside the organization supplying goods and services, the customers are also within the organization doing the supply. Selling is not always required for this type of customer/supplier relation. An assembly line worker’s customer is the one to whom he/she provides goods or services. A doctor’s customers are the patients. A teacher’s customers are the students. A planning manager’s customer is the production manager.

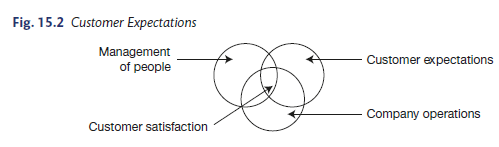

It is imperative for all internal customers in an organization to be satisfied to ensure complete satisfaction of the external customers. If one of the customers is dissatisfied, he/she can create havoc in the business process. Proactively unearthing and quenching the demands of internal customers is one of the basic requirements of TQM. However, the specification of requirements made by the internal customer should ultimately satisfy the external customer. From a company’s viewpoint, customer satisfaction is a result of the following three components as shown in the Figure 15.2.

- Company processes (operations).

- Company employees who deliver the product and service.

- Customer expectations.

Customer satisfaction should not be treated as a mere slogan. The ultimate target of business is to effectively invest resources to satisfy customers through empowered people in the face of market competition, so as to realise a profitable return on investment. Customer satisfaction leads to customer loyalty, which drives up market growth and share. A noted Japanese management scientist, N. Kano has identified three dimensions of customer requirements as shown in Figure 15.3. They are:

- Basic requirements: Basic requirements relate to those that the customer takes for granted. These are never a subject of negotiation. For example, safety of an airline.

- Performance requirements: These relate to customer expectations that are negotiated and agreed. For example, the flight schedule of an airline.

- Delight requirements: These relate not only to meeting customer expectations but exceeding them. For example, a fashion show during a flight.

Today, competition requires not just customer satisfaction but demands customer delight. It has been found that a delighted customer takes six times less effort to retain in comparison to a fresh customer. A delighted customer not only helps bring down the cost of sales but also is the best insurance against competitive moves.

Developing a successful customer service system can be one of the most rewarding goals you achieve for your company. The following seven steps can be used effectively to retain customers:

- Top management commitment to the concept of customer focus.

- Know your customers and what they like or dislike about you.

- Develop standards of quality service and performance.

- Recruit, train and reward good staff.

- Always stay in touch with customers.

- Work towards continuous improvement of customer service and retention.

- Reward service accomplishments by staff.

3. Customer Perceptions of Quality

One of the basic concepts of the TQM philosophy is continuous process improvement. An American Society for Quality survey on end-user perceptions of improvement factors that influenced purchases showed these rankings: (1) performance, (2) features, (3) service, (4) warranty, (5) price and (6) reputation.

4. Need for Customer Focus

Internal customers are people working with the organization who have to be served a motivating experience for them to replicate and carry out the same to the external customers. Customer focus has to be started with employee service. Dr Kashmira Pagdiwalla, Director, HR Operations, Intas Biopharmaceuticals Limited (IBPL) echoes the same thought, “An organization will succeed only when customer needs are satisfied. Changing the business focus to a customer-centered paradigm has a broad-reaching impact across the organization. It gives many companies an opportunity to revisit their company as a whole and improve business processes and achieve significant return on investment.” She goes on to say that with a proper customer-focused organization, one can:

- Build on what you accomplish each year in increasing your customer assets and verify it with hard numbers. A more structured work environment that allows for creative thinking needs to be in place.

- Establish meaningful policies and processes that produce results.

- Manage people through information instead of going through people to get the information you need.

Box 15.1 discusses the customer-centric initiatives of Fiat India.

5. Buyer-Supplier Relationships

Almost every company purchases products, supplies or services for an amount that frequently equals around 50 per cent of its sales. Traditionally, most companies follow the “lowest bidder” practice where price is the critical criterion. The focus on price, even for commodity products, is changing as companies realise that careful concentration of purchases, together with long-term supplier-buyer relationships, will reduce costs and improve profits. Deming realised this and suggested that a long-term relationship between the purchaser and supplier is necessary for economy. If a buyer has to rework, repair, inspect or otherwise expend time and cost on a supplier’s product, the buyer is involved in a “value/ quality-added” operation, which is not the purpose of having a reliable supplier. By developing perfect buyer-supplier relationship, no rework or inspection is necessary. Several guidelines will help both the supplier and customer benefit from a long-term partnering relationship:

- Implementation of TQM by both supplier and customer: Many customers (e.g. Motorola, Ford, Xerox) require suppliers to operationalize the basic principles of TQM. Some have even requested the supplier to apply for the Baldrige Award. This joint effort provides a common language and builds confidence between both parties.

- Long-term commitment to TQM and to the partnering relationship between the parties: This may mean a “lifecycle” relationship that carries partnering through the lifecycle of the product, from market research and design through production and service.

- Reduction in the supplier base: One or more automobile companies have reduced the number of suppliers from a thousand to a few hundreds. Why have 10 suppliers for a part when the top two will do a better job and avoid problems?

- Get suppliers involved in the early stages of research, development and design: Such involvement generates additional ideas for cost and quality improvement and prevents problems at a later stage of the product lifecycle.

- Benchmarking: Both the customer and the supplier can seek out and agree on the best- in-class products and processes.

How does one become a quality supplier? This of course depends on the criteria of the buyer. The criteria required to be certified as a quality supplier in the automobile industry are that the management philosophy of the CEO should support TQM, techniques of quality control should be in place, the desire for a long-term lifecycle relationship, best-in-class inventory and purchasing systems, facilities should be up to TQM standards, automation level should meet quality standards, R&D and design should support customer expectations and there should be a willingness to share costs.

Source: Poornima M. Charantimath (2017), Total Quality Management, Pearson; 3rd edition.

1 Jun 2021

1 Jun 2021

1 Jun 2021

1 Jun 2021

17 Jul 2021

17 Jul 2021